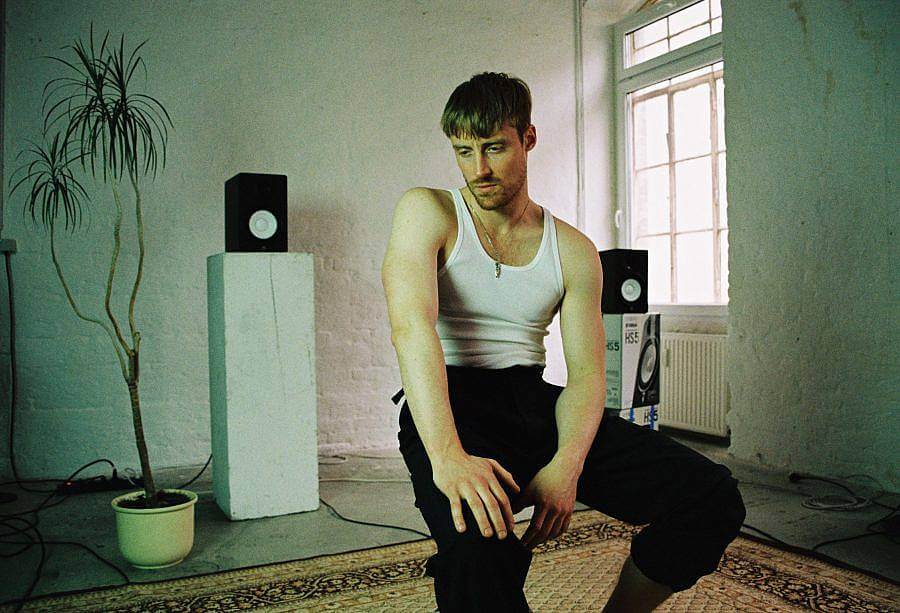

Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

I’m a composer and performance artist.

My work falls somewhere between music and installation/performance art.

I like to write music and focus on the way it is performed, almost as if movement is part of the musical score.

Also, text is slowly becoming more important to me, and poetry is forming an important counterpoint to the music I’m making. I was a close collaborator of the artist Anne Imhof since 2012, where I wrote music for and with her and Eliza Douglas and worked on shaping the musical installation of her performance works.

ANGST II from Frieze on Vimeo.

How did your interest in music and performance begin?

I started playing piano and producing electronic music in my early teens. Music was a constant occupation outside my regular school activities. But when I started my BA studies in electronic music, I totally capsized and fell in love with contemporary dance and performance. At this point, dance became a constant occupation outside any music-related activity. Eventually, I moved to Germany to study choreography.

How does working in Berlin and Brussels influence your practice?

I love the people that I have around me. Both cities feel somewhat less stressful than other metropolitan areas and they make for a more supportive and creative environment. In Berlin, I especially love to move between the art scene, music scene, and the club culture.

Spat From My Mouth from Bill Johnny Bultheel on Vimeo.

How have you been approaching your practice amidst the reality of Covid-19?

The beginning was very stressful. Now gazing into the abyss of a second lockdown, I’m just hoping that not everything will grind to a full halt like last time. I’ve been thinking a lot about movement and space. Since we can’t really share physical spaces with others anymore, I tried to develop performances that occupy different spaces. There has been some focus on the production and expansion into working with film.

I’m also trying to develop new relationships between music and text. Or trying to rethink how lyrics could work.

How has your working relationship with Steve Katona evolved?

It’s going very well. Steve is finishing his studies at the UdK Berlin and we will be working together on a couple of projects in the coming year.

In Spat From My Mouth, you offered your audience a “faux concerto” filled with blue light and a mystical machine. What influenced the production of this performance at Pogo Bar?

I was interested in performing in my own work, something I haven’t really done. I performed for Anne Imhof quite a bit and used to perform in the performances of New Forms of Life, a collective I was part of from 2010 till 2013, but I never performed as a musician in my own work. So I decided to write myself a piano concerto. Unfortunately, I’m not really a virtuosic pianist, and I had to put the emphasis on something other than my shaky fingers.

I exchanged the sound of a piano snare with the sound of the wind. An empty blow. I really enjoyed debunking the seriousness that comes along with composing piano concertos. And instead of delivering virtuosity, the concerto became an immersive sonic experience, with a body that was struggling to relate.

In your previous interview for Dapper Dan, you cited that an” instrument is essentially an interface; a machine that turns movement into sound.” Can you explain your perspective, and how it’s reflected in your music practice?

I think this is a really important aspect of my practice. Just like in the piano concerto, I like to look at instruments as objects that display the body.

So instead of seeing them as sound-producing machines, they are objects that stand in counterpoint to the body.

Each scale or harmony is locked into specific positions or gestures on the instrument. The manner in which holes, snares, or keys are distributed on different instruments can be seen as a movement map, a choreography written into an object.

I remember working with an old organist in Italy who showed me how to play a Bach melody using only the foot pedals, and it just looked like a really weird funny dance. Here was an instrument that demanded this old man to use his entire body to exhaustion to play this simple jolly melody.

I don’t know if this little pretext for my performance ‘Shadow Hunter’ with Alexander Iezzi is necessary here, but I feel it somehow makes sense. This performance started with the idea of making music for hunters, developing a hunting music machine. But we tried to create a complex idea of hunting. Not one of destruction or greed, but one where we extended one’s limbs into nature and into other bodies. We wanted to give the hunter a complex musical harmony. So we started the performance with this little piece of poetry:

Music strikes an area, not a point. The hunter divides his territory in a melodic counterpoint. He plays the field like a flute. In his dream, he selects a sleeper. There’s so much he hasn’t told you, about how quickly his soul is aging, how it feels like a basement he keep filling with everything, that he’s tired of surviving.

Somehow here the poem became an initial interface, the frame from which to think of performance and music.

Further, considering your perspective on instruments, where does the voice fit into your constructed sonic sculptures. How do you incorporate voice in your compositions and performances?

It’s hard to underestimate the power of a voice, especially in music. The voice brings subjectivity to music, it can give a context and a point of view.

In ‘When doves cry’ I was trying to develop a choir based on an idea in post-humanism and Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. I was trying to think of voices that are enhanced by the prosthetic intervention. I ended up working with Tubas and Countertenors. Countertenors nowadays are just very skilled male singers that can sing in high registers most men cannot. They stem from a history related to castrati, boys that underwent physical incisions to change their hormonal development and therefore matured with voices that were totally unnatural to the male body. Luckily this practice is illegal now, but counter tenors could take over the repertoire by developing new singing techniques that bring the voice to similar heights.

Tuba’s on the other hand can be thought of as prosthetics that drop the voice to its lowest possible register. Brass instruments historically started as voice amplifiers, something like a megaphone, but then the addition of valves and pipes transformed the voice quite radically into a tempered instrument. “When Doves Cry” is a choir consisting of Countertenors and Tubas, two instruments that originate with the human voice but are prosthetically enhanced, serenading over an industrial city.

What sounds, movements, and genres are influencing you right now?

The next piece I’m working on is an opera for four metal drummers and a baroque flute quartet. Let’s see what happens, at the moment I’m still just collecting ideas.

You’ve described your works as sonic sculptures or installations. When the audience enters, they become further communal experiences. How important is the audience for the actualization of your works?

I think the audience needs the freedom to wander through composition, and not be subjected to only one perspective. Live music is a three-dimensional happening, it sounds different in every corner of each room.

When Doves Cry from Bill Johnny Bultheel on Vimeo.

Can you talk a bit about When Doves Cry, and the ways it activated space, as part of the ‘Disappearing Berlin’ program of the Schinkel Pavilion?

When Doves Cry was taking place on a rooftop in Berlin. It was composed as a sort of serenade to the city. On an elevated platform on the rooftop, I installed one large speaker that could rotate around its own axis. We called it the lighthouse.

All the music was projected at the horizon, the audience was only witnessing the projection of this music into the distance.

When collaborating with Imhof and others, what processes do you go through to build the compositions in relation to intention, space, and movement.?

One of the first things I discuss with other artists is the architectural speaker setup of the performance. I always try to customize a speaker setup that is specific to the space in which the event takes place. Then we discuss together how different scenes take place and how the musical architecture and composition can emphasize this. Space is always a starting point.

What are some of your favorite sounds or silences?

I like to create silences. I love any sound that comes close to it.

Do you have any upcoming projects or shows?

If the pandemic doesn’t lose its temper, I am hopeful some shows will happen next year. 🙂

Interview composed by Amanda Roach.