Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

I just turned 27 and started living in a new country. It feels like a new chapter in my life right now. I was born in France in a city called Orléans and had lived in Paris from 2010 to 2015 when I moved to Pittsburgh under the pretense of a study abroad program, but just wanted to move there. The choice of Pittsburgh was pretty random back then. As an avid watcher of the TV show Queer as Folk, I was curious about life on Liberty Avenue. It was at that time that I started to dedicate myself to my art practice. This was after a tumultuous undergrad experience in political science where I dropped-out twice and had various jobs. An art career felt like something much more manageable here. In France and even in Paris, I knew very few artists, even less that could actually get by. I’m not saying that the situation is ideal here—far from that—but there are more opportunities and ways to have a practice. I graduated from an MFA program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the Fiber & Material Studies Department last Spring and just set up my studio here in Montréal where I think I am going to be settled for a while.

I make work from my personal experiences, often dealing with intimacy and desire. I am committed to exploring and using techniques used for decorative purposes as a focal point. I draw a parallel between forms of adornment seen as excessive or artificial such as French Rococo motifs or couture embellishment and how individuals like myself have been historically considered deviant. While decoration is often seen as needless, I see it as a tool for self-determination and aspiration, a place to explore one’s identity and desire.

What artists have influenced your practice?

There are so many but here are a few that I am thinking about a lot, I had the chance to meet most of them: Josh Faught, Ebony Patterson, kg, Joyce Scott, Anne Wilson, Jeffrey Gibson, Stephanie Syjuco, Pierre Fouché, BCALLA.

How did your interest in art begin?

I think like most people it came very young, I was the one always drawing in the family as a kid or making something with stuff I collected (key chains, matchboxes, labels of soda, and things like this). I started to embroider around age 9. I would spend at least a few weeks every summer with my grandmother in the south of France, by the Mediterranean. She was a cross-stitch kind of woman and would spend a few hours every afternoon working on a project, carefully following a pattern and getting her thread from a very organized binder that contained every color you can imagine (sparkles included). I was captivated by it and she eventually gave me a piece of Aida cloth and a needle. Since then, I’ve never stopped embroidering. There have always been a few projects around, some more serious than others. So my first interest in embroidery came from then, but as I grew up it became somehow a shameful thing to say. But I really loved it. With my pocket money, I would spend hours at the sewing shop and buy magazines with DIY kits. Later I understood why I felt shameful about this, and it’s when I realized the power behind this technique, and behind cloth in general.

Due to Covid-19, we’ve been forced to connect in different ways, often through screens, how has this impacted your practice?

I’m still adjusting to it, like probably most people are. I’ll start with the good things since I’m in a very privileged situation of having the time and space to even make work. I was asked by a friend teaching at SAIC to come to give a talk to his class via zoom the other day; something like this from Montréal wouldn’t have been possible before. I hope that one of the things that come out of this current online world is limiting unnecessary travel and reigning in our carbon footprints. Wearing sweatpants nonstop is pretty nice too!

I am a lover of objects, textures, and smells. The IRL experience is essential for me, and as much as I believe that a good image of someone’s work can share some things, it will never replace the original. I know that it is going to take a while to get back to a world where we can safely look at art together, but I’m confident it is going to be this way. In the meantime, I’m allowing myself to be more playful in the studio (currently full of nail polish and faux eyebrows), diving into slower processes and making work for when the real experience of it will be back.

In the meantime, instead of “online viewing room” experiences, I’m looking forward to the comeback of printed magazines and other publications that can be disseminated across the world and remain a physical experience. I’ve recently bought some magazines for myself, something I haven’t done in a few years, which probably came from the need to flip the pages, smell the ink on the glossy paper, and fold the corner of a few pages. Instead of trying too hard to translate art into a jpeg, I’d love the opportunity to think of different ways to present things in a magazine format. I guess I’m putting some feelers out there, I hope that’s okay!

What erotic possibilities do you see in the everyday object?

There are plenty and this question takes such a different meaning at a time where most of us are at home all of the time in the perpetual presence of our stuff. I enjoy faucets and other piping fixtures, especially when they are shiny. These days I spend a lot of time online looking at crown molding and doll-sized decorative wooden fixtures. I think a lot of them are very sexy, they literally dress up the wall.

Last summer, while back in Pittsburgh I took part in a residency at an artist-run space that once was a traditional middle-class city house. Part of the work I made there was in reaction to this environment and the sense of homecoming I felt once back in the city. I made several curtains and swags out of various mesh fabrics for the three windows of the main gallery, thinking about the curtain as a potential erotic device for the person living there and their neighbor. I also made a wallpaper design in which I inserted clips of pornographic imagery. The whole exhibition – Indecent Exposure – was an attempt to give to the viewer a smilingly mundane and quite boring space to look at until they start getting close and notice the double tone throughout the rooms.

The erotic is the merging of two spheres: the private and the public, eroticism doesn’t happen in your bedroom but rather outside of it. Daily objects have the power to merge spheres and transport you somewhere else. This quarantine experience proved this to be right more than ever for me, while at the same place every evening, looking at this specific printed cloth or a bar matchbook takes me somewhere else and keeps reactivating memories. They also become places for fantasy. I think that’s the erotic potential of objects that interests me most these days, especially when the only reason to go outside is to go on a walk. I’ve been incredibly smitten by outdoor staircases here in Montréal these days, they are architectural stepstones to stranger’s lives and I love walking by them imagining what happens inside.

What is it like living and working in Montreal?

It’s been very good, I’m so lucky this city became a possibility for me. If someone had told me a year ago that this is where I would live I would have said “How?” A year into grad school my partner got offered a job here and moved out of Richmond, VA where we had been living before I moved to Chicago.

I officially moved out of Chicago last September after five full years in the US: Pittsburgh, Baltimore for a few months, Richmond, and then Chicago. I arrived back when the Republican primary was happening and I left when the country was more anxious than ever and seriously in peril when it comes to its democratic institutions, the safety of its people, and being able to get by.

Mid-March when Covid hit the US and my school shut down I remember talking to my partner on the phone, he was in Montréal and I was in Chicago, about the possibility of the border shutting down. The next morning, I bought a plane ticket for that same day, packed a few beads and pieces of fabric with me, said an awkward goodbye to my friends at school, and left. Two days later the border closed and is still closed today for non-essential travel. So, I got to discover the city in unique circumstances, empty for a couple of months and with no businesses opened other than supermarkets. We took long walks most days and kept discovering new places and hidden parts of our neighborhood, St-Henri. It’s pretty exciting to be here in a culture that merges the French and English languages. I was already at a point of getting creative with both languages, but now I have daily opportunities to jump from one to the other.

What is your current studio/workspace like?

I very recently unpacked my studio and set up a spot in the apartment that I enjoy working in. It’s in a corner, a space I really enjoy being in and think about. I nerded out a bit when it came to making an organizing system for all my threads. It’s the first time in a couple of years that all my beads are in the same place and that’s pretty great.

Mesh, a material that teases at concealment and one that’s associated with desire, is central to your work. Can you discuss this?

Oh yes, mesh is my favorite material ever, and one of the reasons why is that it can pretty much be anything. Anything that is a network of material and holes is mesh – from cotton to steel, from gauze to metal fencing. I like this idea of a very broad term that refuses categorization per se; it is not about what the thing is made out of, but the fact that the absence of it (a pattern of holes) is essential to it. Matter and absence sit on equal grounds. I think there is a queer poetic attached to this idea, as well as its difficulty to categorize. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick talks about queerness as an “open mesh of possibilities” in Tendencies, and I don’t think this word is here by accident.

Mesh textiles are my absolute favorite, from athletic spandex mesh to handmade lace. They sit at so many intersections: gender (both of the wearer and the maker), class, and more generally, identity. I personally think that mesh is both hot and queer. The material has a counter-culture vibe attached to it, from the radical dykes to the punk scene by way of MTV with Madonna and her iconic Lucky Star black tank top look, to a super faggy Ken Doll from 93 named ‘Earring Magic Ken,’ that wore a lavender mesh top and a cock ring as a necklace. I’ve never been able to find much writing on the tracing of this material and its wearers and its constant back and forth between function and embellishment and mainstream and counterculture. I keep lists and thoughts on it and keep being amazing by this material.

In my work, mesh is ever-present; I either embroider on mesh, hand-marble mesh, I cut it, restitch it, shape it… It’s like a never-ending play with this material. The more I research it and think through it, I feel like all these meanings attached to it become embedded in the work. I’m not expecting every viewer’s brain to work the way mine does, but I enjoy the multiplicity of responses about it, and generally, queer viewers get where I am going with it.

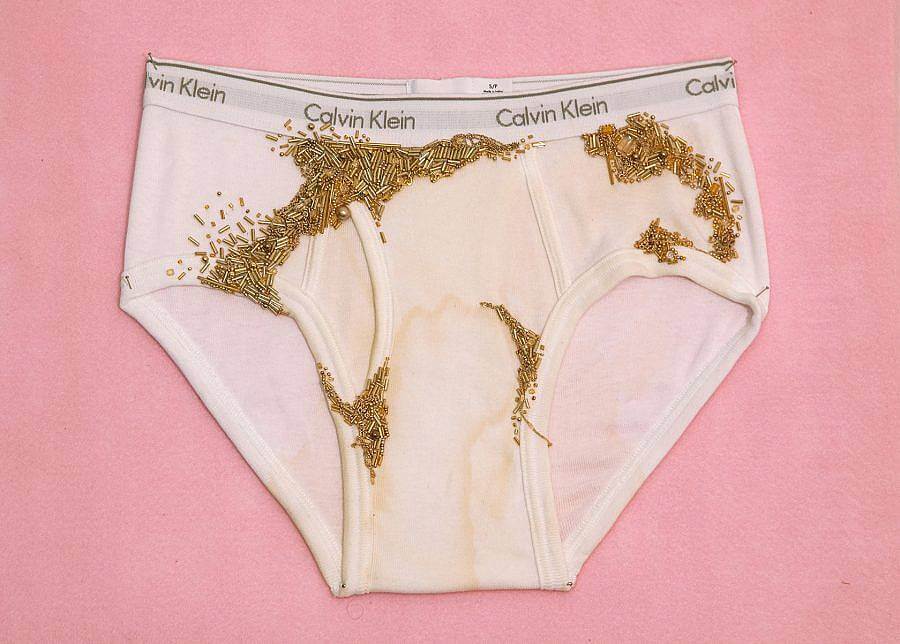

In your 2016 “Stained,” series, you transformed human excess, urine, and semen, into ornate, opulent displays. How does excess continue to shape your work?

I would say that it is pretty much everywhere and that I myself have excessive tendencies. Excess is what is not needed and I think I almost exclusively deal with materials, techniques, or ideas that are not needed. On purpose. It’s in the extra, the added, that you can see signs of human behaviors: how things are arranged, a gel color pen in a diary, a gem on a cell phone cover, a hand-drawn eyebrow line. These marks usually tell us a lot and reflect a need for adaptation, customization, making something truly yours. So whether it is literal bodily excess, such as semen, or a shiny glass bead, these signs of excess ask to be taken seriously. I’m currently spending a lot of time with glue as opposed to needle and thread with gems and trims to decorate small gay bar memorabilia. Under the layers and sparkling nail polish and pearl stickers, I’m deeply sad and worried about these spaces, the well-being of their staff, and afraid of the wave of closing everywhere in the country. It felt natural to start using these materials, slapping gems on them as signs of care, and anxious denial.

Can you discuss the use of double entendre in your work?

I love this question, and it reminds me that I need to add “double entendre” to my list of French phrases used in English. For everything I’m making I always imagine several scenarios of people responding to the work. A friend made fun of me because I’ll have conversations with myself in the studio very often and he caught me doing it once. How obvious or encoded the work is, depends on what I’m trying to talk about. I feel like earlier works were much more direct and in-your-face—cum stained underwear covered with beads for example— but more recently I am interested in more quiet gestures. I’m hoping my work operates like a knowing wink from a stranger in an anonymous crowd.

My work changed when I moved to Chicago, I was back to a large city again after two years in Richmond, Virginia. I was back in environments like gay bars, bathhouses, and sex clubs. I wanted to bring some of the experiences, sensations, and camaraderie of these places into my work without making a spectacle of it. I wanted to mirror the fact that taking pictures of cruising spaces cannot and should not happen with some of the formal elements of the work. The series of objects I was working on when the first Covid closure happened were very abstract renditions of objects and furniture from two specific bars in Chicago. They were purposefully left un-named back then to build in secrecy in the world itself. Everything was encoded: I used to write down the words “fags” and “faggot” in the marbling bath I would keep my fabric in, turning these slurs into decorative motifs, I would embroider the floorplan of the basement of the bar with beads or even reproduce the scale of an existing fixture.

Now, six months later in a completely different world, I am feeling a need to name these environments, to have their existence directly acknowledged because they are threatened by extinction. Over the years I’ve been collecting matchbooks, coasters, and business cards of gay bars dear to me from the different cities I’ve visited and lived in. I am currently making some shadow boxes for each of them, each personalized by a memory from the place. I’m hoping to get some sort of a “perverted scrapbooking couture” vibe out of it, the personal photo book of a fag like me that feels the need to memorialize these environments right now.

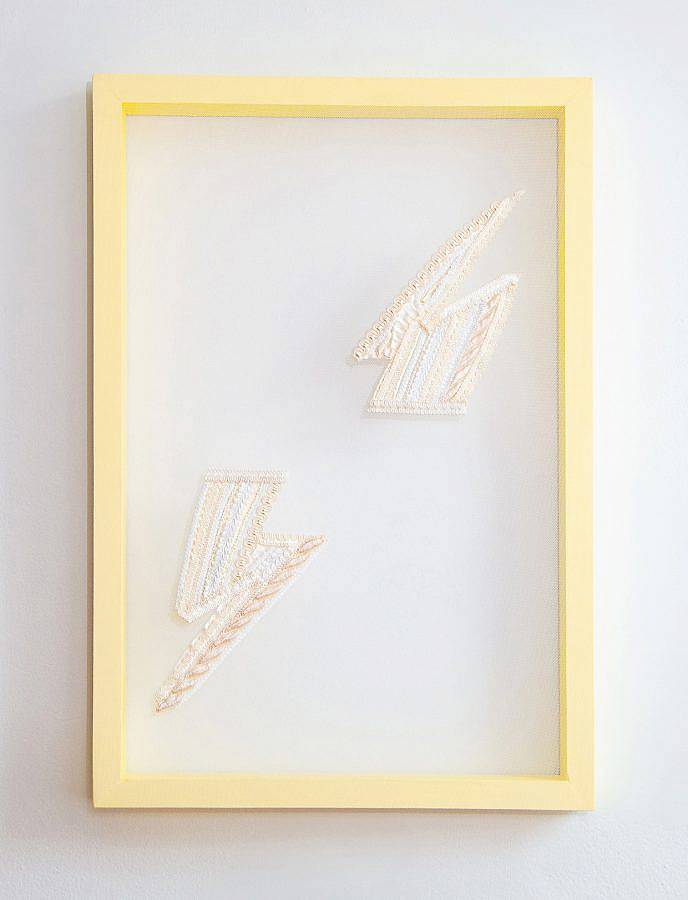

You recently learned to needle lace and spent a great deal of time on a small mesh needle lace portrait. Can you discuss this new direction in your practice?

Yes! As I mentioned earlier, it felt impossible to make anything during the first few months of quarantine. I was about to finish grad school, and installing my thesis exhibition a few weeks after the closings. The last five weeks of my MFA became Zoom class and it was all very weird. I was very lucky to be working with awesome people at school that made that whole experience more manageable as well as friends from my cohort. I didn’t do much until a few weeks after I graduated – which is ironic. I wanted to go all-in in a time-involved project and figured that since I didn’t have many ideas on what to work on, I might as well learn a new skill that I was always obsessed about. Needle lace is the modest sister of bobbin lace, you simply need a needle, some thread, and some patience—not a crazy amount of bobbins and complicated systems of twisting. The only book that has been following me since I lived in Paris is a needlework encyclopedia by Thérèse de Dilmont and I instinctively took it with me as I was packing in a state of panic when leaving Chicago, and I finally went through the needle lace chapter of it a few months later.

I translated a sexy pic from a Twitter guy giving the “gay hello” (a butt wink) into a romanticized vignette à la Fragonnard from a desire to bring some materiality to the digital flirting experience. The whole thing is about 6” x 4” and took me about six weeks to make. It made total sense back then to dive into a tiny surface for a while when the whole global context was (and still is) completely impossible to make sense of.

All of your works, whether it’s deconstructed fetishistic items or barely-there partitions, seem to entice the viewer into engaging with them. How important is viewer engagement to you, is there a desired effect you’re intending?

I like the word, “entice”, and I think it really fits what I’m trying to do. I love embellishment techniques for several reasons but the main one is because it’s tantalizing. It’s a shimmer caught in the night, that makes you want to come close and potentially destabilize your understanding of beauty. Coming close, bending over a surface, entering one of the urinal partitions walls—these are motions I am hoping to get from my audience. I like the gallery space a lot, the white cube is essentially a cruising space: you linger around a piece and move quickly in front of another one, circle back, gaze. I remember going to galleries in Paris my first year living there, these were definitely places to flirt and sometimes pick up guys. I like the idea of having an audience reproducing these gestures of cruising without necessarily realizing it. Artist Vincent Tiley speaks about “asking the audience to act pervy” and I don’t think there’s a better way to put it.

The other kind of engagement I’m hoping from the viewer is some sort of pleasurable feeling, that the decorations and the shiny do the trick. I love how artists and writers Neil McInnis and Judith Leemann write about the glamourous as “both a focal point and a mode of critique” and these words are with me every day in the studio. We were talking about “double entendre” earlier, and that’s another element that I love to play with. There’s often a hidden joke or a crass reference somewhere, sometimes more obvious than others, and having several levels of appreciation for a single work is something I really enjoy.

Interview composed and edited by Amanda Roach.