Tell us a little about yourself and what you do

My name is William J. O’Brien (he, him, his). I am an artist and professor currently based in Chicago. My art practice spans different media but I primarily use drawing and ceramics as the foundation. Recently I have been talking about my work as one of active listening from myself to the viewer. I was raised in a religious household and grew up as Queer in rural Ohio. As an adult I do not consider myself religious but feel my work deals with aspects of secular spirituality and ritual. Most recently after a series of unexpected events, the most recent bodies of work primarily address issues with loss, trauma, and grief. My work does have strong autobiographical and identity-based concerns but it also is about physical labor (queer labor specifically), process, and experimentation.

How does your relationship to your work change based on the medium you’re working in?

It depends on how much money I have to spend on materials; it depends also on how much physical time I can spend on the work. I see my use and choice of materials to be about listening and tonal response. Different materials elicit different tonal responses to the viewer. Sometimes I have talked about the work similar to music composition in terms of how a physical object may look, but also smell, sound, and taste at the same time. The texture and softness of clay has a much different sensory response to felt or even metal. I have intentionally aligned myself with artists who prioritize the use of the body and senses over the mind as the vehicle to connect themselves and the viewer to the work.

Do you view your large drawings as a meditative practice?

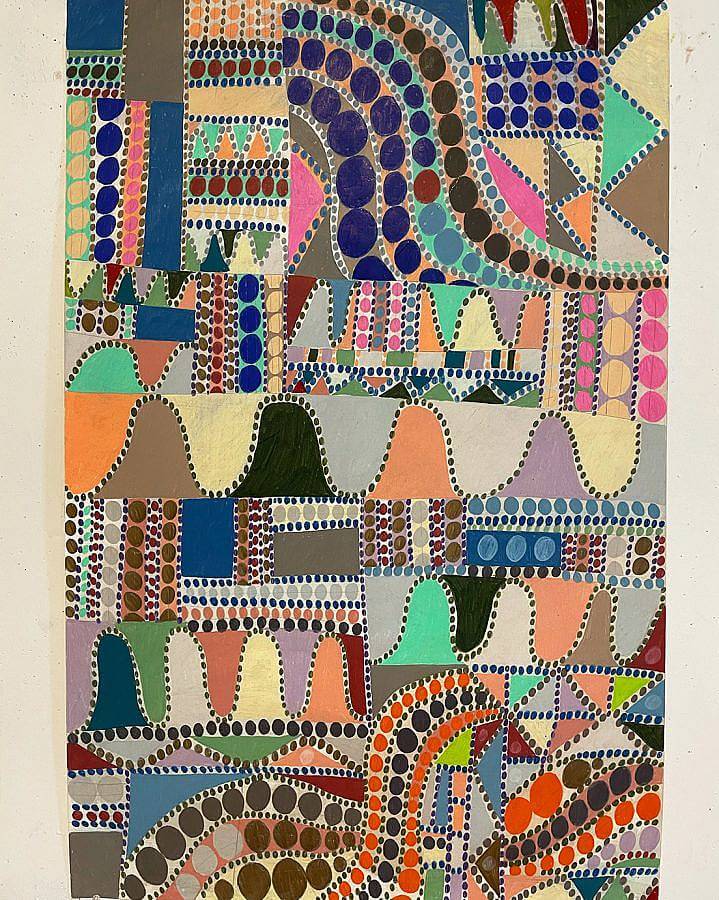

Yes and no. I think sometimes people have this idea of meditation or being meditative as being about calm, or retreating, or even beauty. In the Buddhist lineage I was trained under, meditation is about connecting and seeing the world clearly. The good, bad, and ugly in yourself and the world. Through this very humbling approach to connecting with yourself and the world and seeing things more clearly offers the opportunity for insight and wisdom. These drawings are made from this same space. The drawings are very physical to make. They take my whole body and attention. Oftentimes they are made from transcending and transforming difficult circumstances. They are also I think architectural maps of my emotional and psychological body.

While in the studio, how conscious are you of autobiographical elements influencing your work?

Am not sure if I am necessarily conscious while the work is being made but often I will think of a particular person either living or dead to pay homage to within the work. This can exist as a real, imagined person or character but I also think it can be fun to imagine for yourself an alter ego that can make a completely different tone and body of work to break up the pressure of feeling we have to be aligned to ourselves all the time.

How do you consider the viewer and accessibility of your work?

I never wanted my work to be just considered in a context that was just accessible to the art world. Growing up in a working class family I had a very limited experience to art and art making. My aunt had cerebral palsy growing up so I had the privilege of learning a lot about different ways of seeing and marking art. This early exposure to artists with disabilities as well as the awareness of the limits and accessibility to art to a wide range of the world has been a big influence in me advocating and supporting using cheaper materials as a means to open up conversations about access – who gets to make art and why. As I progressed into my path of making work as an adult, it was really one of transforming a great deal of trauma and pain from childhood but also reclaiming a sense of innocence and play that was lost along the way. So by appearance one could look at my work and see that it is formal and uses traditional materials but actually sometimes the most radical art you can make is allowing yourself the permission be innocent, playful and even to create beauty.

Can you share more about your evolving relationship with religion and how it functions within your practice? (Particularly in regards to your 2019 exhibition, Shame Spiral, at Atlanta Contemporary.)

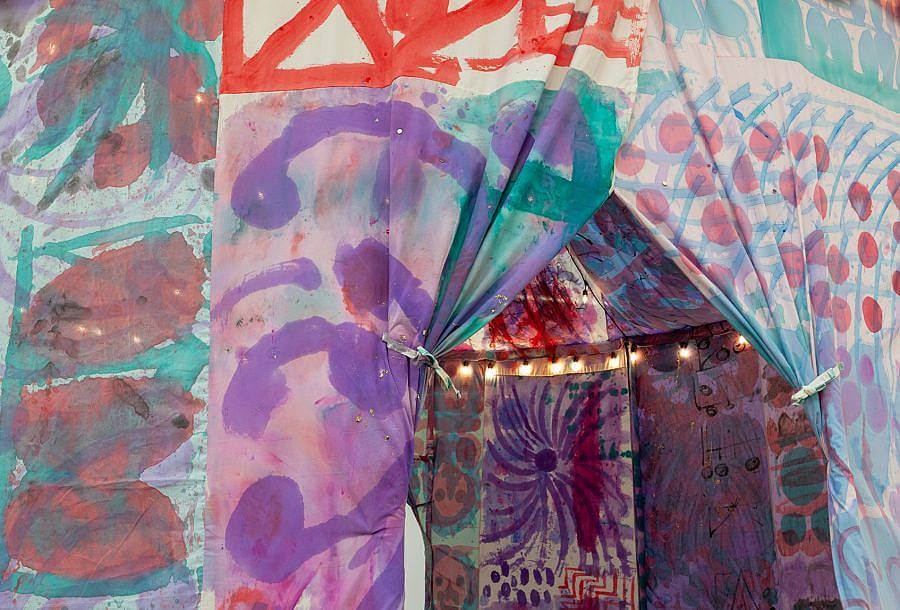

I think the word religion triggers a great deal of different responses in everybody. Looking back on my childhood I guess I could say I was raised in a cult of sorts? The transition to coming out as Queer and reclaiming the spiritual side of myself was one of the best things that I can say that happened in my adult life. Unfortunately religion has been used to control and hurt many people, often the most vulnerable and disenfranchised in our society. But at its core, religion does have the potential to bring people together in community and create a sense of magic through ritual. These two components for me have been part of my interest in how the secular, spiritual and also sexual can exist within society. In my art practice I was always fascinated by the private ritual of the maker and the object. Ritual and the ability to infuse psychological and emotional content into an inanimate object has the potential to create the space for healing and insight. At the time the Atlanta Contemporary Art show was happening, I was asking myself a lot of questions about art spaces, specifically galleries, museums, etc. and why they felt so isolating. The tent structures I view as potential shields are also temporary shelters and spaces. I wanted these installations to serve as a structure inside of a structure. An emotional structure to contain the work but also a structure to provide space for contemplation and reprieve from a world that oftentimes does not allow people, especially the disenfranchised, to feel or experience that.

As a teaching artist, how do you view your responsibility to younger artists, particularly in a rapidly changing world?

First off being a teaching artist is one of the most humbling and privileged experiences you can have as a maker. I am really fascinated about why people make art more so than necessary what they actually make. One thing that I am trying to earnestly do as a teaching artist is be genuine, open and human. Some of the best teachers I have had were very human and real and not afraid to show vulnerability and/or weakness. I try to approach teaching in this same way of being real, open, but also one of observation. Unfortunately institutions and art schools can be both wonderful places to connect and find community but also have created problems in terms of accessibility and damage for artists who are trying to create their own path in this field. I see part of my path currently as acknowledging the harm that art school has created for some individuals and also making strides towards holding space for people to grow and be themselves. Within this space I hope it can and will instill a sense of self worth and confidence in what they are doing and be able to thrive and grow wherever they choose to exist in their practice. There has been this historical notion of tearing down the student and rebuilding them. I don’t approach teaching in that way. I look and observe with my students for several weeks before offering feedback. I honor and respect wherever their practice exists. I also feel for me I try to learn and acknowledge areas of myself that need to change and grow. I see it as important for me to use this position in society as a means to pull people up rather than push them down if I can.

What are you reading right now?

I am reading The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa, Volume 2, Snacking Cakes by Yossy Arefi, and White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo.

What are you most looking forward to this year?

My partner and I are hopefully going to Alaska this summer on vacation. I am also excited to show the newest body of work, “Orbs”, that I started during the pandemic. It will be a part of a group show this summer at Marianne Boesky Gallery in NYC as well as at a four different architecturally sacred locations for each season this next year.

Interview composed by Kaitlyn Albrecht. Edited by Ruby Tresch and Kaitlyn Albrecht.