Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

Hi! I’m an artist. My background is in drawing and printmaking, but my practice has since expanded into lots of different formats — furniture, installations, workshops, artist books, audio guides, events. I’m disabled and most of my work over the past 5–6 years has been about accessibility and disability culture (or cultures).

In the, “Do you want us here or not?” series, you’ve created a series of benches, chair cushions, and seat cushions, all in art spaces. Can you talk a bit about how this series has evolved and how it frames inaccessibility in exhibition and art spaces?

Walking and standing are hard on my body, so I am very attuned to seating options as I move through the world — I’m always looking for spots to stop and rest. I had the idea for this project in 2017 after a particularly painful and tiring museum outing. I was frustrated with the scarcity of seating and realized that making artworks that are also functional benches is one way to get more seating into exhibition spaces.

These pieces use text and say things like, “This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. Sit if you agree.” or “I’d rather be sitting. Sit if you agree.” The text is a way of channeling some of my frustration and playfully drawing attention to the way that the act of sitting itself is an expression of a need or desire for rest.

In recent years, how has disability advocacy played a role in the development of your work?

I didn’t set out to do advocacy — I’ve needed to do advocacy work because in my role as an artist I encounter structures and systems that don’t work for me and don’t facilitate participation for my disabled friends and colleagues. I think my work can be read as advocacy in that it offers possibilities for what access-centered experiences might feel like.

Can you talk a bit about your ongoing project, “Alt-Text as Poetry”?

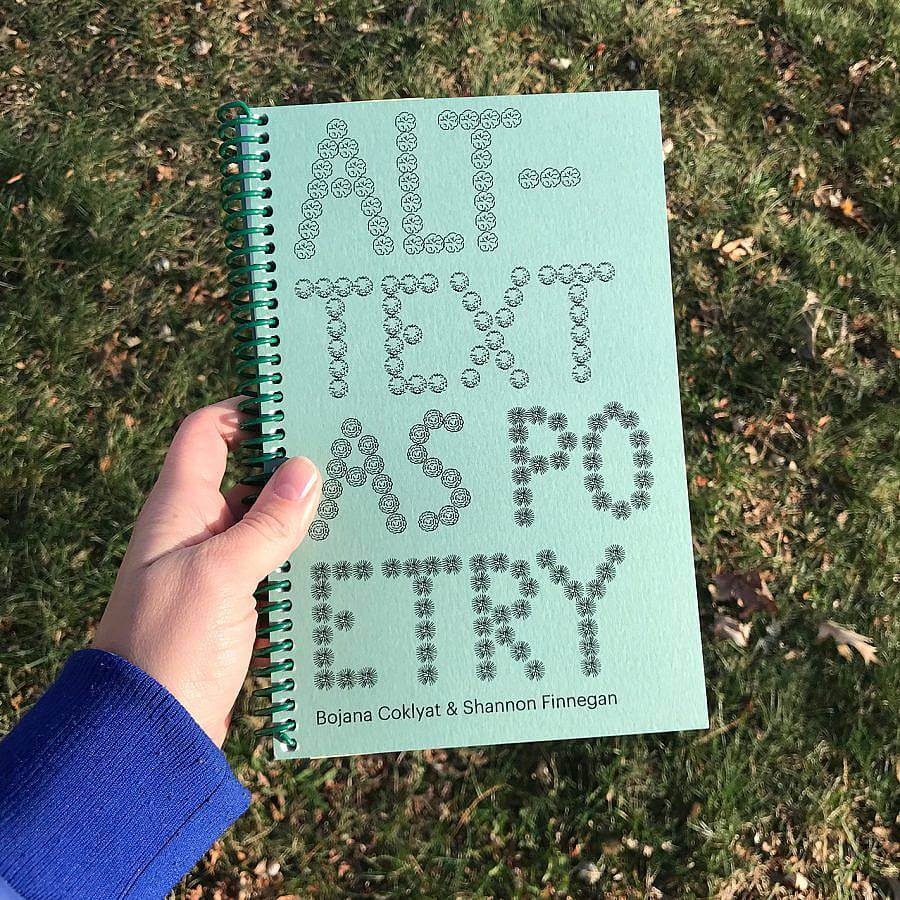

Alt-Text as Poetry is a collaboration with artist Bojana Coklyat — we’ve been working together on this project for about two years now.

Alt-text is an essential part of web accessibility. It is often overlooked or understood through the lens of compliance, as an unwelcome burden to be met with minimum effort. We’ve been asking, how can we instead approach alt-text thoughtfully and creatively? Our project reframes alt-text as a type of poetry and creates opportunities to practice writing it. If you post images online (on social media or websites), you should be including alt-text.

The project has taken a few different forms. It started off as a workshop curriculum, and we’ve done the workshop with about 30 different groups now. This fall we also released a workbook that is a self-guided version of the workshop. We’re also working on a blog called Alt-Text Study Club, that will highlight examples of alt-text or image description with commentary, and gather other resources and info that support the ongoing study and practice of alt-text writing.

We’ve approached this topic as non-experts — for us, the point of the project not to tell people how to write alt-text, but rather to think about it and practice together with other people. Like all accessibility practices, writing alt-text requires ongoing dialogue and collaboration.

I also want to mention that lots of other disabled artists and thinkers are doing related work. We’ve highlighted some of the people we are learning from in the Ecosystem section of our website.

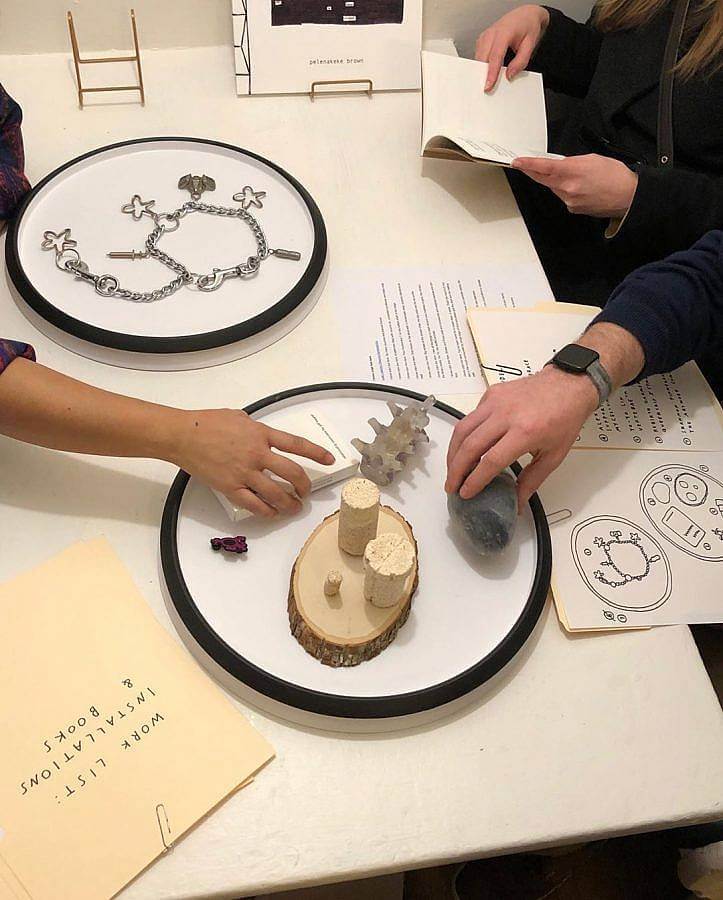

In your Here to Lounge project at Nook Gallery, you curated a seating-centric art experience, where the “art comes to the visitor,” and not the other way around. What was the process like for curating Here to Lounge, and how would describe your approach to togetherness for the project?

Yes, I have been excited about the idea of an exhibition where, as a visitor, I can sit and have the artwork come to me (rather than how it usually is — me traveling from piece to piece in a gallery space). Nook Gallery is a kitchen nook, so it has a lovely built-in table with a bench on each side. I realized, at that scale, a lazy susan is the perfect way to circulate objects.

Talking with Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo (an artist and the lead curator of Nook Gallery), we decided that bringing other disabled artists into the show would be a good way to activate the idea. I also felt excited about bringing other artists into the show because I think of my work as interdependent with the work of other disabled artists, as what I make is not possible without what they’re making. This project mirrored that interdependence (the lazy susans aren’t an artwork until they are brought together with other objects).

In selecting objects, I prioritized things that could be picked up and touched — objects that facilitated multimodal engagement. Trying to push back a bit on ocular-centrism. I also knew a lot of the artworks would need to be shipped to Calfornia, so I gravitated towards things that would travel easily, especially artist-multiples.

Your projects center on messages conveyed through text, what advantages do you feel there are to playing with text, words, and messages when creating art?

I like the directness of text — I can speak directly to the viewer. I also like that it is translatable — both into other languages and across senses. For example, something made as audio can relatively easily be turned into a transcript. Or something made in a visual format can be described or read aloud.

What are you reading right now?

I tend to have a few books going at once. Right now, I’m in various stages of reading:

Feminist, Queer, Crip by Alison Kafer

Where I stand by John Lee Clark

Wow, no thank you by Samantha Irby

The Young Lords: A Radical History by Johanna Fernández

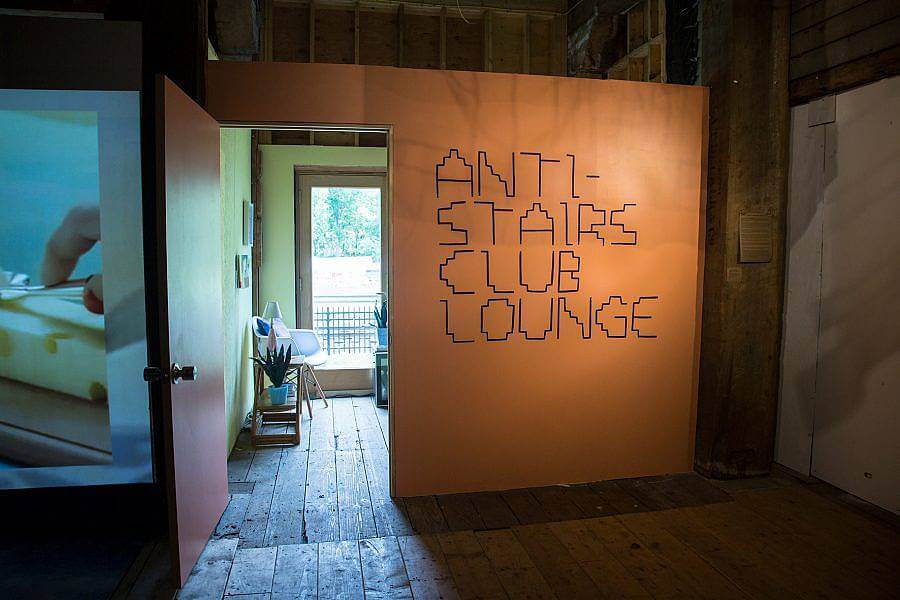

Anti Stairs Club Lounge is a space “exclusively for visitors who cannot or choose not to go upstairs,” that took place at Maxon Mills, a seven-floor building with no ramps and no elevator past the first floor, and the Vessel, a structure made of 154 connected stairways that centers the act of climbing stairs.

Looking back on “Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at Wassaic Project,” and “Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at the Vessel,” can you discuss how the lounge space evolved from a small curated lounge on the first floor of Maxon Mills building to a public protest of the Vessel?Will there be more iterations?

Anti-Stairs Club Lounge was originally conceived of as a site-specific work for the Wassaic Project. At the time, I was trying to understand how I might engage with an inaccessible exhibition space as a disabled artist. The lounge was installed for two years and I thought it would end there. But then I heard about the Vessel. I was feeling so angry that $150 million was being spent on something so inaccessible, so I decided to re-tool the Anti-Stairs Club Lounge for the Vessel.

I was wary about how Related (the real estate company that built and owns the Vessel) would respond, so I translated the structure of the lounge into things that would be hard to point to as not allowed there and that we could pack up easily if we were asked to leave. So for example, instead of enclosing a space like a lounge, all participants wore bright orange beanies — so it was still easy to tell who was “in the lounge.”

And yes, I think there will be more iterations. I’ve been thinking about “naturally-occurring” Anti-Stairs Club Lounges — places that people who share an aversion to stairs already gather. For example, inside an elevator. For a show called Alarming Specificity (which ended up being canceled because of COVID-19), I had planned on making a vinyl piece for the interior of the gallery’s elevator to mark it as an Anti-Stairs Club Lounge.

Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at the Vessel, 2019. Hudson Yards, New York City, NY. Photo by Maria Baranova.

Do you have any upcoming projects?

I recently made a short video with Louise Hickman titled Captioning on Captioning. It’s being presented online by LUX through March 2021. Our friend and colleague Kevin Gotkin recently tweeted about the film saying, it “offers a rare chance to better understand how real-time captions work. And why the relationships that produce them are so precious and complex.” I love that description of it. Louise and I have also been dreaming up some other projects and I’m excited to work on those in the new year.

What is your studio space like?

I currently work out of my apartment. I have a desk and spread out to the living room floor when I need more space. My desk has pens, pencils, and lots of index cards, which I use to make notes to myself and write to-do lists. I’m currently in a spread-out phase because I am working on packing and sending out orders of the Alt-Text as Poetry workbook.

Interview composed and edited by Amanda Roach.

Alt-text image descriptions by Shannon Finnegan.