Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

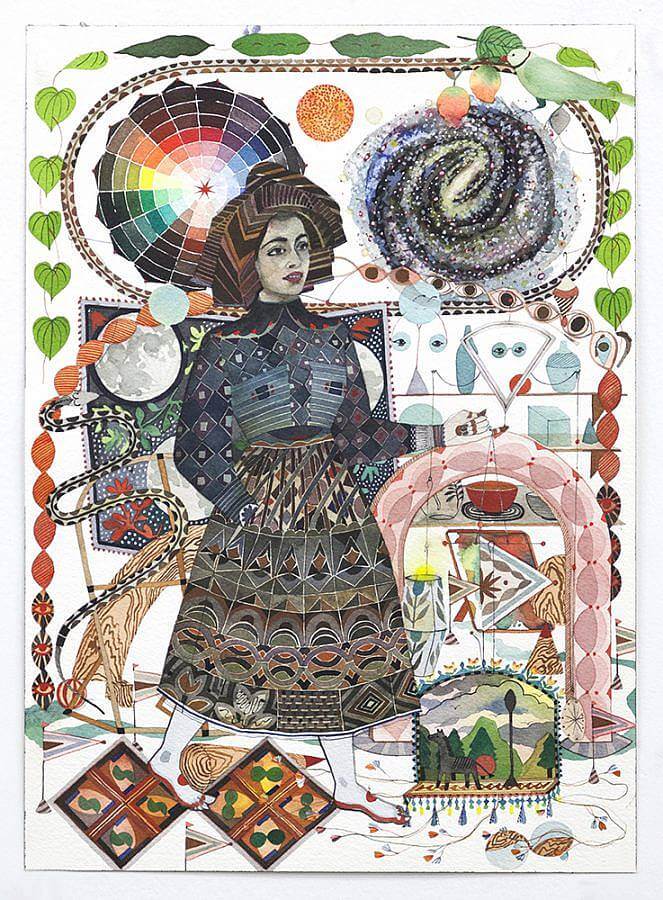

I’m the oldest child of my family, and after me come many sisters and one brother. Some of us are cousins. Much of what I love and think about was once a pastime of an older family member. For example, both my grandfathers and mother loved gardens and gardening, my mother is a very gifted gardener, my aunt is a designer who has worked with many materials including textiles, and my father has a beautiful voice and adores music of both people and birds. Both my grandmothers have taught at schools and my paternal grandmother ran a preschool in the house I grew up in — I attended this school too. So it seems that now, spending most of my time teaching, thinking about birds and gardens and songs, art in narrow and wide ways, I’m merrily cycling through their personalities, trying it all out.

How did you get started as an artist?

My aunt taught me how to hold the pencil right and draw! And then the school I went to was very lovely in the way the teachers paced how and when children could use pencils, pens, and graduate from using crayons. From ages 4 through 6, most of our days were spent gluing glace paper circles and other shapes with very grey glue, and using sets of 12 and 24 colour crayons. Once a week, we made paintings with red, yellow, green, and blue on big easels. Then from ages 7 through 15, the schools I went to had a weekly art class where we made ‘memory drawings’ or scenes from imagined other lives. Quite a lot of it was stereotypical (Birthday! Divali! A village!), but very fun. My art teacher from my early childhood insisted that nothing has an outline and my teacher during my teenage years insisted we outline all objects and figures with a black marker. I loved them both! There were not many opportunities to be immersed in art-making outside of these short classes and so my parents would look for painting competitions and workshops in newspapers, just so I could sit down with other children and make art.

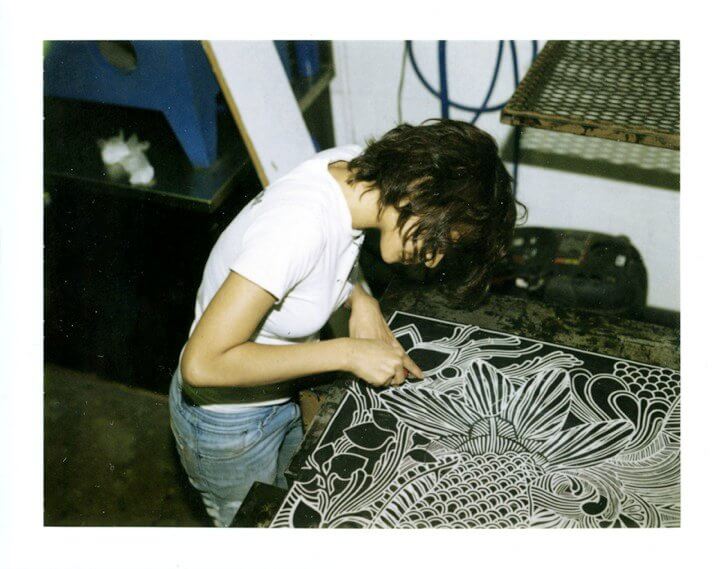

After 10th grade, I didn’t have any formal art education for a couple years while I attended junior college, but this is also when I started working as an assistant to a visual merchandiser, Yamini Namjoshi. She was 27 when I was 17 and I was amazed at how someone could make a life out of art, fabrication, and design. Then I attended college to study printmaking, graduate school to study sculpture, and here we are! There is no clear line between then and now except for the support I had from my family who never asked me to do something else, and loved what I made like only family can.

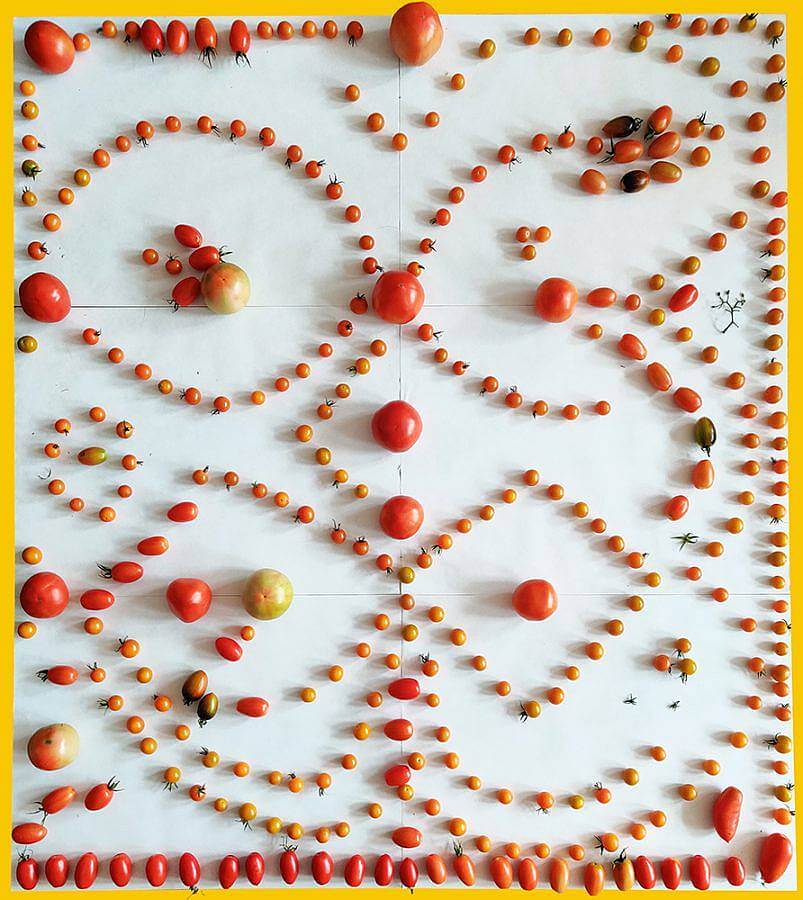

What role does gardening or farming play in your practice?

It must be the time we are in. I don’t know how someone can be conscious right now, have several options in front of them of what they can do, and then (if they are fortunate enough to be artists) not think about the long game of their material adventures. I don’t think art can be about the environment, about the anthropocene, about whatever way in which it’s popular to discuss our climate anxiety, if its very parts are the problem. I was and remain very tired of the kind of art I was seeing that uses plants as props, or whatever else reminds one of nature, all for the benefit of the artist and their image as someone socially aware and caring. Our relationship to our world, Nature, cannot stop being subject matter, right now at least.

I started gardening and learning to farm when I saw these tendencies in myself, and when I began to learn to picture what the length of my own life might be like and what I hope to have made by the end. It’s definitely not sculptures or paintings or anything solely relevant to people. I don’t want to leave behind so much stuff that will surely be trash. One way, for now, is to work and make like a bird does. For example, a weaver bird and his nest satisfies my love for spatial hierarchies, constant building, light and colour and sound, and food. All of course, through gardens.

How do you think about family in your work?

I am stuck to my family. I live very far from them, but I am emotionally stuck to them and think of them in all things I do throughout the day. Every other day I talk to my mother about what I’m making, cooking, and with my sister too. When I’m home I often make my work at the family dinner table and so everyone can give their opinion, tell me if they think I’m going to finish on time or not. Sometimes I get help too.

You’ve documented your ongoing project, Attraction Foundation, through Instagram for several years now. Can you talk about your intentions for this piece, how it has evolved over the years, and how you use Instagram in your practice as a whole?

In 2014 when I started Attraction Foundation, it was a geotag for my house before I realized that this helped anyone locate it. It was safer to keep it as a hashtag (despite my deep dislike for it) to archive a set of videos and photos that were made at home, in my studio at VCU, and my walk up and down Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA. I had just gone through a lot of heartbreak and was by myself. I was trying to figure out my relationship to attraction and seduction in the absence of a lover, and in an ever lengthening period of celibacy! It was like the kind of devotional love that borders on desire. The kind that people hold for that unattainable and sometimes nonexistent divine lover/god/goddess/creature, going right into feelings of flirtation, beauty, attraction, charm, longing without waiting for a subject to cause them.

I was so excited by the kinds of videos I could make on Instagram then; first 15 minutes long and then 1 minute, with a very basic editing capacity. I felt that I could make parts of myself visible that I would be too shy to share in person, but wanted very much to be associated with me. I don’t make these videos anymore. The app works at a different pace now, much faster, interrupted by advertisements, product placements, and suggestions of influencer accounts. I am hoping very much to find a way to divorce myself from this tiresome medium but I don’t know how. The problem of Instagram and much of social media is that it limits at least my imagination as to what is possible without it. Right now as an artist it seems I have to use it or I’ll disappear. I know that’s not true. I don’t like that most of the art I have seen this year has been on a miniscule screen. The short answer is that I used to use it a lot, dozens of posts a day, and now I’m trying to forget about it. On the other hand, it’s also become a powerful way of covering events outside of traditional media, especially in countries without a free press. This particular project is an odd thing to continue in what I see the best use of the app now. And the vanity required to make these videos is disappearing as I get older.

Can you describe your workspace and how it evolves in relation to what medium you’re working in?

Oh! I love work surfaces! I love tables, fixed ones and makeshift ones. My favourite workspace is my living room because it has my dining table and both of these places are close to the kitchen. I can have a snack and have tea and have lunch and dinner and make what I need to all at the same time. I’m fortunate to have a studio these days, but I prefer my home. Other workspaces I love: kitchen counter while making dyes, any clean floor while making quilts, studio only while making messy sculptures, a shared weaving studio while weaving, and garden for gardening. I also love the studio we carry around inside our heads while walking.

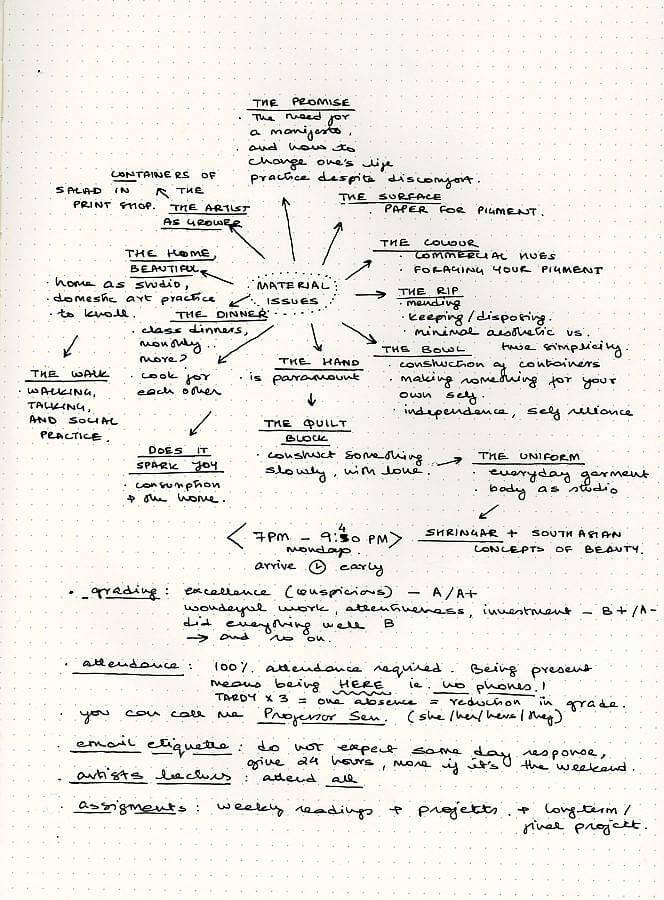

As an Assistant Professor of Multiples and Distributed Art at Williams College, how would you describe your teaching style? What elements of this led to the DREAM TIME lecture series?

In anything I teach, I hope for what is always at the center is the magnificent capacity of our hands and eyes and selves: to reach a harmony and understanding with material, sense what she can do, where she comes from, where she will go, and to see one’s place in the very long strand of imaginative vibrant minds. I don’t find that art is good for, or often efficient, at leading any kind of urgent change and I don’t see why it has to be. But the time spent transforming thoughts and visions into conventional forms of whatever we recognize as art, in whatever time, is a very powerful exercise. We are asked to imagine what isn’t there and in doing so, many sets of possibilities are entertained.

DREAM TIME was organized at the same time as a class I taught remotely in the fall of 2020, Drawing Dreaming. The speakers were artists who are drafting alternatives to the present and proposing futures outside of what seems inevitable. In class, we could barely see what the other was doing, and I wanted there to be a way to use this time to plan and envision another kind of time for us: me and my students.

Many of the mediums you’ve worked in are tied to a long history of craft. Can you talk about your relationship to craft tradition and mastery?

I owe everything to craft and to craftspeople.

Can you share more about #lunchy and the process of putting together DEAD PLANET COOKBOOK?

The book came together very fast. It was dragging for a while and then one day, with the help of my friend Riki Matsuda who was visiting me in Brooklyn, I completed it. For the few years before the book, I noticed how much time cooking took up, and how little time I had to do anything else. Perhaps this is not a good tendency, but I wanted to make something of this time that was more. I wanted all my meals to count as my work because they are a lot of work, they take up my afternoons and evenings, they are delicious, they are worthwhile.

What are you reading right now?

On the train from Moynihan Station to Albany-Rensselaer, I read an essay my friend sent me. It’s by Asa Seresin and it’s called ‘On Heteropessimism’. I have loved many men deeply and have felt the feelings Seresin describes, of disliking one’s affection for men given how much pain can be caused by misogyny in heterosexual relationships. I loved it.

Interview composed and edited by Ruby Jeune Tresch.