Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I’m a painter and bricoleur, and grew up between Japan and the United States. I work in the realm of bricolage, so I collect and work with materials like clothing, furniture, written notes, and photos to explore the poetic, material affect, and time-space relations of atmosphere–as a site of possibilities, a site of being, and a site of representation. My very first job was in New York at a fashion magazine, assisting a fashion editor, and I think that became incredibly formative to my own understanding of materials, construction, and world building. Now, I spend most of my hours and days in my art studio, if not outside on a walk.

Describe the process of bricolage and how you use it in your practice. How does this technique differ from assemblage?

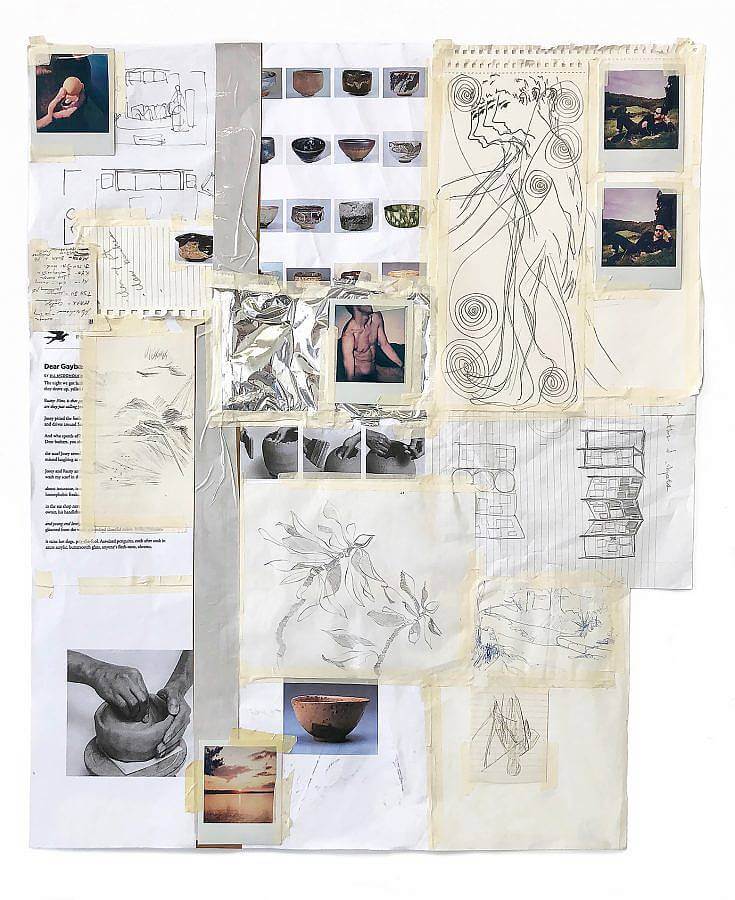

Bricolage is the art of embracing the readily accessible, the improvised, and the democratic–a way for materials and ideas to cross social and class divisions within a unified whole. It kind of acts like a method for responding to what’s already around you and as a way to follow intuition, emotions. Where assemblage stops, bricolage begins; bricolage embraces the possibilities of piecing together materials alongside ideas and relationships. For me bricolage is a more sensitive approach, where material affect and a sense of atmosphere can lead the way.

Your bricolages often resemble a form of poetry, bringing together the disjoined to articulate new ideas. These pieces include written poems as well with pages printed directly from the Poetry Foundation website. What draws you to poetry and how do you see it functioning in your practice?

The poetic is so important in my work; it’s what happens when everyday experiences are filtered through the eye, mind, body, and hand–what it means to be a human, a spiritual being having a natural experience. Ideas of accessibility are so important to me as well, and the Poetry Foundation is an amazingly accessible resource for anyone to find and read and experience poetry. It seems like a natural gesture to include something readily accessible, something that moves me, and place it directly into my work.

You recently apprenticed at the Gee’s Bend Quilting Collective, a historic community of black female quilters in Boykin, Alabama. Can you tell us more about this experience and the piece you made during your time there?

Spending time in Gee’s Bend with the Gee’s Bend Quilters was such a powerful and beautiful experience in many ways. I went with my friend, Bhasha Chakrabarti, because we decided why not learn quilting from those who have embodied the practice for generations. We mainly worked under Mary Ann Pettway and China Pettway, and they would talk about what they saw in materials, find ways to describe improvisational decision-making, and taught us everything they knew about stitching, piecing, and quilting. So I made my first quilt, using old shirts, old yukatas, and other found fabrics. Quilting is obviously an extension of bricolage; how all these disparate parts come together to create a new, unified whole–something that is warm, and invites itself to be close to you.

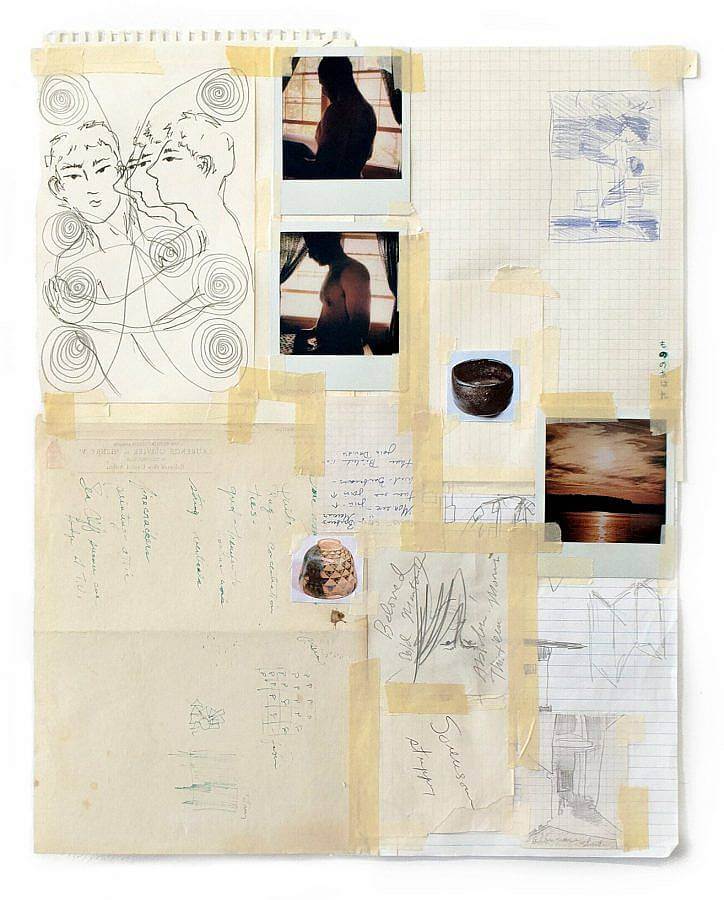

The first year of your Yale MFA culminated in a body of work titled In Praise of Shadows both made from and installed in your home. Can you share more about the process behind these pieces?

This project and body of work started with re-reading Jun’ichiō Tanizaki’s text In Praise of Shadows. The author describes Japanese aesthetic philosophy through the framework of constructing a traditional Japanese home and showing its conflict with Western amenities, turning into a larger, embodied way of examining racial relations between Asian and white bodies. This text became important to me in many different ways, and it was kind of like a key to embracing a sense of atmosphere and decentering Western paradigms of space, art exhibitions, and art-making. The pieces in my installation occupied thresholds, sight-lines, shadowed corners as a way to meld the lived environment within the art, almost like how to live inside an art piece. The bricolage pieces were constructed from my clothing, furniture, mail, drawings, photos, and other things at hand from around my home, so it was more than just living around art. It was like bringing these objects to life and having them live around me.

Many of your past works utilize objects that suggest a level of everyday intervention and decomposition like eggs and oranges. What were your intentions while investigating these specific materials?

Eggs and tangerines have entered my work at different moments, in different spaces, tied to different memories, but the gestures were very similar and are still very present. I’m interested in impermanence, longing, and being confronted with time and how it can relate to the movement through and around space. To be able to witness the natural conditions and aging of material, or to be reminded of a recent memory, is a way to expand space by increasing the experiential time. We have to think of time as broad, encompassing all things at once, where every idea, object, place, moment, exists simultaneously.

If you could collaborate with any other artist, who would it be and why?

Wow. There’s so many, but I think I would learn a lot from a collaboration with Francis Alÿs. There’s something very poetic about his work that for me seems quite sensitive. So for that to further unfold into the sphere of geopolitics is like the right energy, the right way to shift ways of seeing and thinking about the world, and maybe even changing it.

In the fall of 2020, you took a year off from your MFA program to work with North Carolina House of Representatives candidate Aimy Steele and voter engagement groups in the South. Can you talk about this experience and what motivated you to make this decision?

Last year, 2020, mid-pandemic, mid-election, mid-political upheaval, it seemed like the wrong time to focus on school, like it was too selfish to center myself on an individualistic art practice when there was collective work to be done. So I was connected with Aimy Steele, a candidate running in North Carolina, to help manage her campaign. I studied political science in undergrad, and I am so interested in the general space of U.S. electoral politics and its history–like I think it’s so hot. In that space and process of working on a campaign, I was thinking so much about communication, the collaborative, democracy, and pieces–like how the whole country was galvanized, moving together, coming up with ways to not just theorize about a better country, but to take action to create and make a better country. Now a year later, I am still working with Aimy, although in smaller roles, because I believe in her mission for a new North Carolina.

What are you reading right now?

Right now, I am reading Greg Bordowitz’s Volition. This is after I saw his retrospective, Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna be Well, at MoMA PS1 and I was floored. I spent hours with his films and writings there. It was such a beautiful time capsule of his activism and video work during the 1980s through the 2000s, and a very poignant reminder of the HIV/AIDS crisis and the homophobia that permeated the greater culture. However maybe more so, it was a reminder of the poetic beauty of queer community and queer life lived during the time.

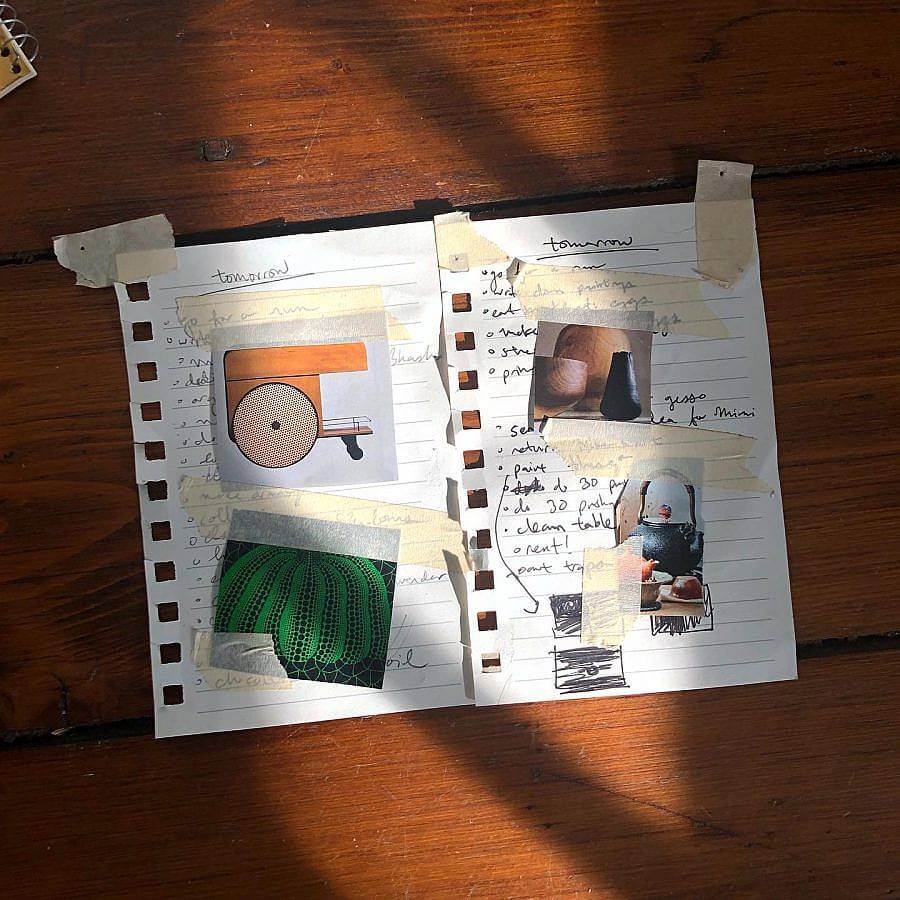

What are some of your essentials in the studio?

My studio essentials are scissors, tape, vintage crystal barware for cocktails, and antique Japanese Imari plates for food. I’m always in the studio, and it seems like the easiest way to catch up with friends is to invite them over, so being able to create a warm space and properly host in the studio is a must for me.

Interview composed and edited by Ruby Jeune Tresch.