Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do?

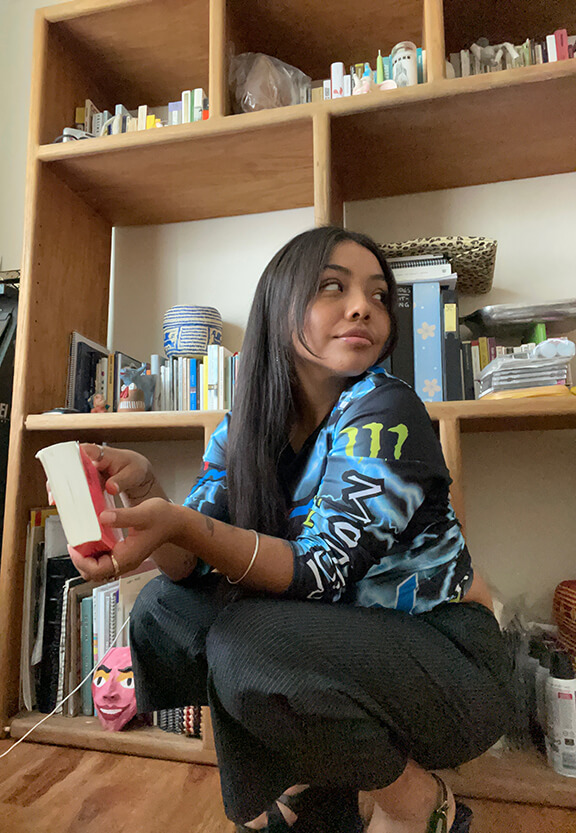

My name is Pamela but I also go by Lucrecia. I was born in Oaxaca, Mexico but I’ve been living in Los Angeles for about six years now. I’m an artist working mostly with photography and sculpture and a caregiver for children between the ages 0-4.

What made you want to be an artist?

More than wanting to be an artist I feel that I came to it by chance. I was making photographs since I was 15 but back then it was more about photographing my friends and my surroundings without really thinking about it. Later on, I was dating someone who was a photographer and he showed me a lot of technical and conceptual elements of photography. It was him and one of my mentors in college who encouraged me to fully dedicate myself to art. Ultimately, I think it was the openness of art both in its process and its outcome that really pulled me in.

How old were you when you moved from Oaxaca, and what impact has it had on you and your practice?

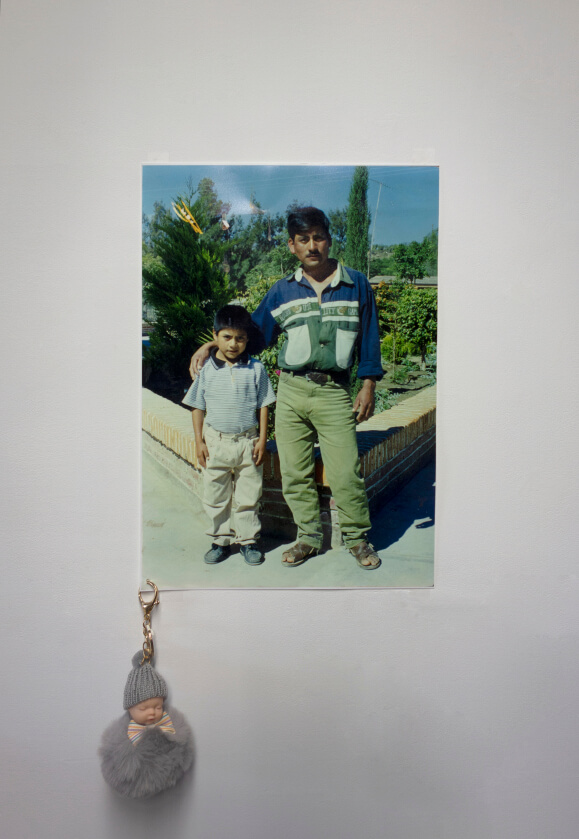

I was 12 the first time we ever moved away from Oaxaca. My family and I first moved to Baltimore where part of my mom’s family resides. We only stayed in Baltimore for two or three years and then we moved back to Oaxaca where I finished middle school and part of high school. On my last year of high school my mother decided to take us back to Baltimore but I always had an unbearably hard time over there so I ended up moving to California to live with my dad. Moving away from Oaxaca was about escaping certain emotional issues for my mother and us but it was also about getting away from the conflict that was unfolding back in 2006 between the state government and the APPO. I think my parents thought that it would be best for my sisters and I to grow up away from the violence and corruption that was unfolding before us at that time.

At the beginning of my practice having left Oaxaca made me a highly sentimental and nostalgic artist. Early on, I gave into a very nostalgic way of art making which I now think can be limiting and I’m suspicious of it since I realize that it’s very easy to fall into the trap of believing in something that was never even there to begin with. In a very Yvonne Rainer fashion I can say; yes, feelings are facts but we must examine these facts too! Coming to the U.S. also helped me better understand the effects of grouping and classifying people based on their ethnical backgrounds. It wasn’t until I came here that I was consistently reminded by other people and by policies that I was foreign to this place. I felt foreign already but there was and there still is a fixation on my condition as a Mexican person. I think even this question is rooted in that to a certain degree. That’s not to say that this kind of othering doesn’t happen back at home because it does but my experience switched from being othered because of my features or my class to being othered because of someone else’s construction of my national identity. All of that is to say that having realized that there are certain expectations of my person resulted on expectations of what my work should be or look like as well. For that reason, I question the work to a degree where I sometimes talk myself out of making anything out of fear of falling into the trap of self-fetishism.

Can you talk a bit about your “Plastic Bag” works?

Untitled (Plastic Bags), 2018 is an ongoing body of work in which I revive images from my archive which I previously considered incomplete by inserting them into plastic bags taken from my grandmother’s bag collection. By insertion and addition, a new image is created while the previous one is obscured. I use the plastic bags as a tool to slow down the reading time of an image as well as to create new meaning by the joining of these two objects. Each bag contains multiples of the same image in order to create the necessary weight for it to be installed. For me these plastic bags are a successful conjunction of the materiality of photography and the image space itself.

What have you been reading lately?

I’ve been really into reading the poems of Rosario Castellanos, Claudia Rankine and Gabriela Mistral and I’m currently reading Zizek’s The Sublime Object of Ideology and a compilation of essays on conceptual art.

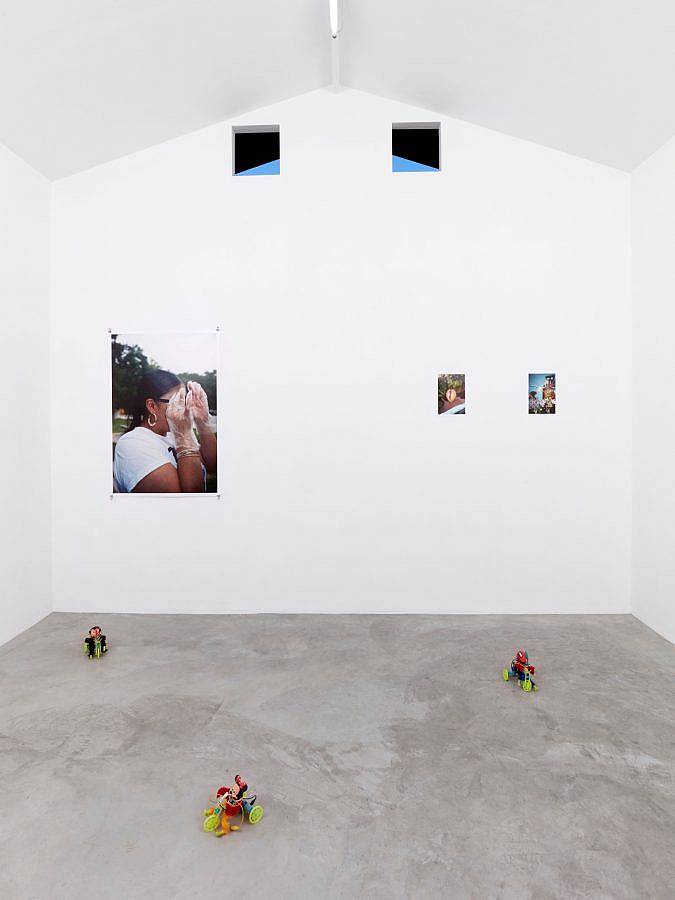

Can you talk about your approach to showing sculptures with photographs in your solo exhibition “Cursi”?

I had been working on the toy sculptures way before Cursi even happened. The toys as found objects interested me because of their evident failure. If you look closely at them, you can see bits of leftover glue or extra fabric or plastic and yet their heads are western cartoons such as Bart Simpson or Mickey Mouse. I saw the toys as symbolic contradictions of aspiring to be so much more than they were; which led me to look at the images I was making and be able to localize a similar attitude in the way I was photographing. When I was laying out the show, I wanted the sculptures to be there since they were the departing point and I felt like they were the embodiment of what the images were trying to evoke.

Do you find it challenging to make photographs in an age when most people see hundreds of photographs on the internet daily?

I actually really enjoy contributing to the mass of images that are born daily. I do see a distinction between the images I make for Instagram and the ones I chose to exhibit but I find it encouraging to have a space that constantly demands that I make photographs. The images I post online are not aesthetically far from the ones I consider to later become artworks. I think that there is a different speed and attitude toward images that are dictated by the platform in which they are presented. My friend and peer Parch Es once talked to me about the difference between art that requires presence and art that doesn’t. He argued that paintings require physical proximity from the viewer while photographs don’t, that photography is an art of absence. That was a transgressive moment for me and it made me realize that photography can be both physical and nonphysical. In that sense, I am optimistic that the way in which images are produced and consumed has the potential to create a power shift for artists who are not already supported by established institutions.

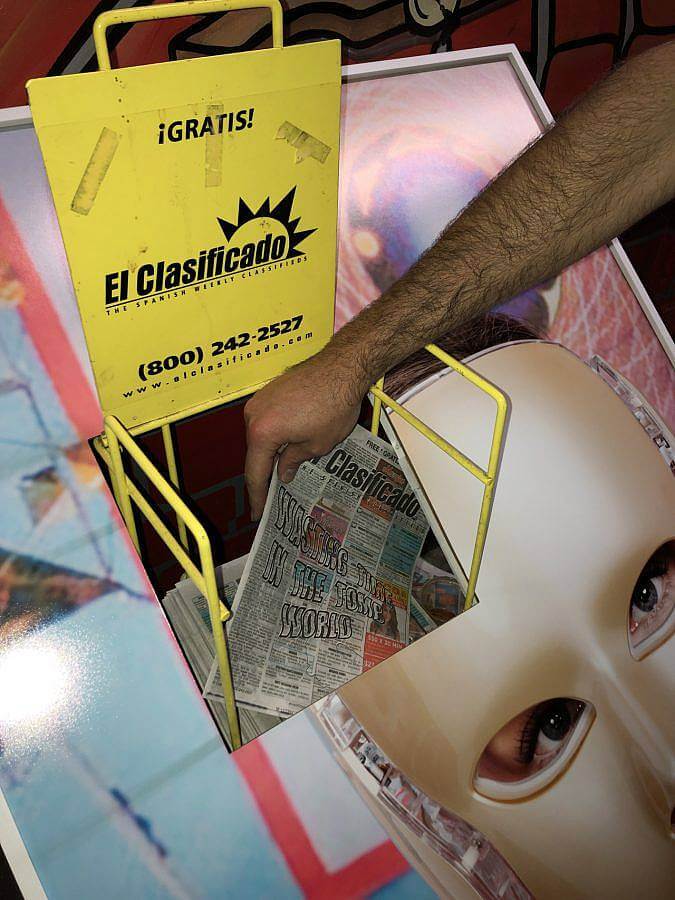

What made you want to begin your project “El Clasificado”?

I mostly started this project because I had just graduated from college and I wanted to find a way in which I could continue to have an art community beyond school. This project also came to be because I was trying to find a certain kind of agency for artists outside of already established institutions such as galleries or museums.

What are your feelings toward the state of contemporary photography?

Feeling wise I love contemporary photography in its vast renditions. I think that photography’s omnipresence and it’s accelerated development is overwhelming and it really creates a binary between art photography and photography as a tool. Unlike other mediums such as painting or performance art, the development of the world relies a lot on photography. This makes me feel confident in saying that photography is necessary independent of its artistic value. When I think about contemporary art photography, I realize that there is a lot of work that relies on the mechanism of the camera and it tries to emulate this robotic or Flusserian effect to the degree that I find the work predictable and stagnant. I believe that an image is so much more than what the apparatus dictates. I also think that the art world is still trying to make up its mind on where photography belongs which I frankly find outdated. The skepticism surrounding the value of photography as an art form or the oversimplification of what an image is or can do are still very much present. Because of its proximity to technological development, I suspect that there is a lot of pressure on art photography to become more like the tools that surround us rather than to expand on its own.

What do you have planned for the rest of 2021?

This whole lock down thing messed me up a little so the rest of this year I’m just trying to get myself back together and maybe apply to grad school or figure out a more sustainable way to be able to live in Los Angeles. As I mentioned before I’m also growing out of a certain way of thinking and making art and I hope to arrive at a new chapter for my practice.

Interview composed by Sam Dybeck.