Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I was born in Olathe Kansas, a city just south of Kansas City. I feel fortunate to have grown up there, as Kansas City’s art institutions were part of the foundation of me wanting to become an artist. I always enjoyed making things but didn’t invest myself fully until after I had worked a retail job for nearly ten years. Working in this environment influenced my work a great deal, as my sculptures and installations often use a similar language to that of retail environments, or store displays. After my retail gig, I went to school full time and got a job as a museum guard, which eventually led to my work as a preparator. The museum, and its practices are, and will continue to be crucial elements within my work and methodology. After ten years of museum work, as well as graduating from the University of Kansas with my B.F.A. I moved to Boise and earned my M.F.A. from Boise State university. Currently I am in Boise where I maintain my studio, as well as working as an adjunct professor at Boise State University.

How did Kansas City’s museums provoke your interest in art-making?

I always remember being interested in looking at objects and wanting to make things, but I clearly remember a field trip to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art when I was in the third grade and feel this is when I knew I was interested in art. I remember quite a few pieces from that trip, but two works really stuck with me. One was a wall mounted, bent car metal sculpture by John Chamberlain, the other was a really large black Louise Nevelson sculpture. Both of these objects had a great influence on my early life as a kid and have remained since.

-

Didn’t Know you Liked to Get Wet, 2019 | Duck butt decoy, plastic pool, cedar, La Croix can, water | 20”H x 70”W x 70”D

Can you talk about the materials you use in your sculptures?

The materials that make up my work are always in flux, as some of what I use I come across through bin digging, craigslist, and thrifting, while others I cast, fabricate, or simply buy. I am very interested in our relationship with nature, specifically animals, so one of the main materials I use is animal imagery. Some of these representations include taxidermy forms, plush toys, and decoys. I handle these materials with a bit of humor, as some of the subject matter within the work is rather dark. I try to use humor as a way into the work, to allow a more comfortable approach. Often the materials in my work are cheap, frivolous, and disposable, which I feel aligns with our culture’s thoughts on some animals’ lives- as something replaceable and meaningless.

Can you elaborate on your process of collecting and how these objects make their way into your work?

I find my material all over the place. I always suggest that people search for their local Goodwill, or similar local facilities. The key is to find the warehouse or outlet locations, as they usually charge by the pound, instead of by item. I also hit re-stores and hardware stores to accomplish most of my fabricating. Unfortunately, I realize that my practice is part of the problem of generating waste, so I try to reuse as much as possible. Many of my sculpture were other sculptures before, or parts of installations. I often will live with an object I find for some time before it becomes part of a work. This process allows me to find more connections with the object by having to engage with it frequently. I do try and keep as much as possible, but space always seems to be a problem.

-

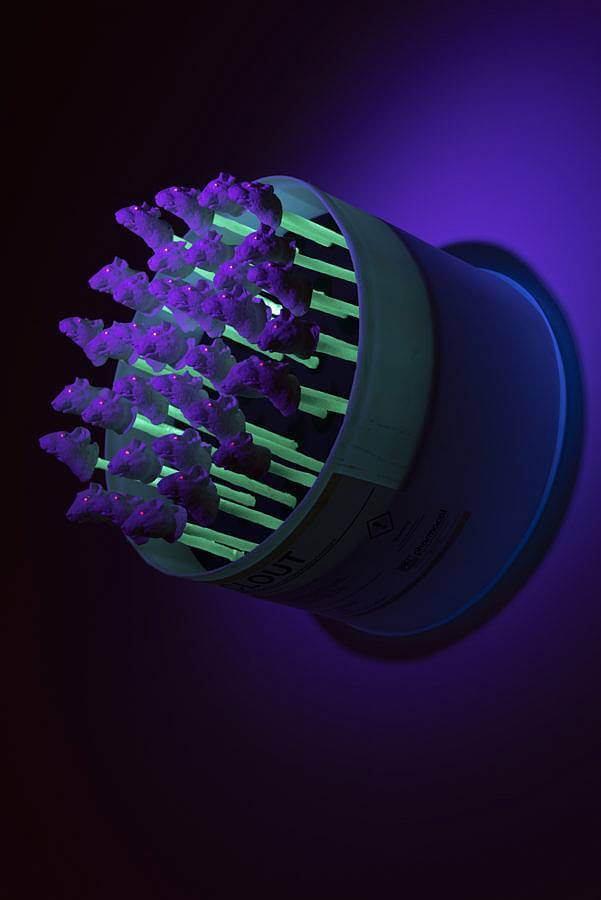

I Like What You Like, 2019 | Cast plaster, Clout containers, dressing material, wood, paint, water, silicone, black light, dye | 24”H x 24”W x 18”D

Describe your current studio or workspace.

My studio is an expanded space that is always changing. Currently, I do most of my preliminary work on the computer researching or in the field searching for objects. I’m also constantly searching for images to inspire my work and often they come from retail advertisements, craigslist, and the news. As far as making, my work really comes together in the gallery, as it is usually in pieces packed away in boxes. I tend to work within these spaces until I need to construct a piece, then I will usually find a suitable space to piece it together and play with it. After this the piece is documented, packed, and stored.

What is it like living and working in Idaho?

Boise, and the surrounding area is absolutely beautiful! I grew up in the Midwest and there wasn’t a whole lot to do outdoors, so it’s a nice change. I’ve always been drawn to the mountains, so this is a perfect location for anyone looking to get active in nature. I feel the landscape here has had an effect on me and my work, as did Kansas. Boise is also growing extremely fast, so there are some really great opportunities coming up for artists in the area.

-

I Love the View from the Places I Don’t, 2019 | Cervidae taxidermy form, chest freezer, photo on fabric, cast plaster, salt. | 168”H x 120”W x 24”D

-

Your Cheap Beer is Filled with Crocodile Tears, 2019 | Inflatable crocodile, air compressor, smoke machine, car battery, pine, hose, foam, mortar, sand, paint | 74” x 96” x 30”

What was the last exhibition you saw that stuck out to you?

I was at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive last February and saw Arthur Jafa’s video work, The White Album. That piece really stayed with me. It was dizzying, frightening, beautiful, hard to watch, but completely mesmerizing. I sat through it a couple of times because I couldn’t stop watching. It’s the most powerful work I have seen in a long time.

What do you want a viewer to walk away with after seeing your work?

I want the viewer to laugh, make a crack about the work, anything really. I want my work to be seen and experienced, everything after that is a bonus. I hope viewers can learn to look at their lives and actions in a new way by showing them work that deals with serious issues but doesn’t seem to take itself so seriously. I feel this strategy allows for the viewing experience to be more pleasurable and allows for the darker, conceptual underpinnings to slowly emerge.

Can you talk about your use of video and sculpture together? Is video simply a form of documentation or does it give your sculpture new meaning?

I feel the videos I’ve made do both in a way. Some are simply documentation, to be able to experience the work, but others like I Told You Not To Use Lifebuoy are intended to be video works. I think of these videos as documentation, but my actions within the videos stray from something purely analytical or evidentiary. I think the videos allow me to discuss animal representation in a clearer way. The videos show how we handle images of animals in our daily lives, but I deal with it in a very tongue-in-cheek fashion, again to make the work more approachable and accessible. The main reason I chose to work with these forms within video specifically, was to use the loop. Our society has a fascination with the repeatable loop, and I feel that it strongly reinforces my ideas concerning the proliferation of animals as commodities.

-

I Told You Not to Use Lifebuoy, 2019 |Still from Video | Dimensions vary

Focusing on this concept of animals as commodities, can you talk about the tension between nature and fabricated environments as seen in some of your photographs and your piece Do Geese Dream of a Down Filled Heaven?

Part of my process and research is to actively seek out sites such as these. I am constantly looking at the variety of human constructions within nature, as well as mental constructs we implement when concerning animals and ourselves. The photography work acts as a journal of seeing for me, looking at the mediations and objects we construct, and how they impact our experience of nature. Similarly, the installation work, like Do Geese Dream of a Down Filled Heaven?, deals with tension between nature and our created environment, but differs slightly as it deals with the unknown, internal processes of an animal’s mind. This is to draw attention to the fact that we acknowledge some animals’ mental and physical agency, while ignoring others.

-

Left: Serpent Self, 2019 | Plush snake, rope, mirror, sintra, paint, meat hook, foam. 192”H x 36”W x 14”D | Right: Do Geese Dream of a Down Filled Heaven, 2019 | Goose decoy, artificial hedge, video projection, led lights, pillows, wood, paint | 24”H x 96”W x 92”D