How did your interest in art begin?

As far back as I can remember, I’ve been scribbling on something, always making a mess. I claimed the identity of an artist early on, probably 2nd or 3rd grade. Suddenly I was hawking Tom Brady portraits for $2 on the playground at school.

Really though, video games, Dragon Ball Z, and being an obsessive fantasy reader pushed me deeper into a creative practice. In a perfect world, my division of work and play would be similar to what it was when I was 10. I’m almost there. Since the pandemic, I was playing dungeons and dragons three nights a week—this is the level of nerd I aspire to keep up! It’s fraught, of course. With restaurants re-opened and unemployment waning and some big ass student loan payments around the corner, my definition of play is going to have to change.

I do miss my Beauty Bar family, of course—but I’m so grateful that they haven’t had to open yet. If you eat out at a restaurant right now or drink at a bar, the least you can do is tip 50%.

How has living in Chicago influenced your practice?

I moved here for grad school, which has undeniably had a huge impact on my practice. There were some rocky edges in the beginning with pronouns – everyone has a learning curve, and grad school is so chatty. That made it difficult to build close relationships for a second there. I will say that I left grad school with a lot of support, love, and comfort in starting an art career in Chicago.

The city itself has been good to me– from working at Beauty Bar to playing in a softball league to house parties (back when that was a thing), to great food, to the lake. I’m the kind of artist that has rocks in their shoes when it’s time to go to an opening, but I’ve seen more art in the last two years than I did in the same amount of time in NYC. There’s an energy here that’s undeniable to me. It’s amazing to have so many artists all in one place. Chicago keeps it weird.

What is your current studio like?

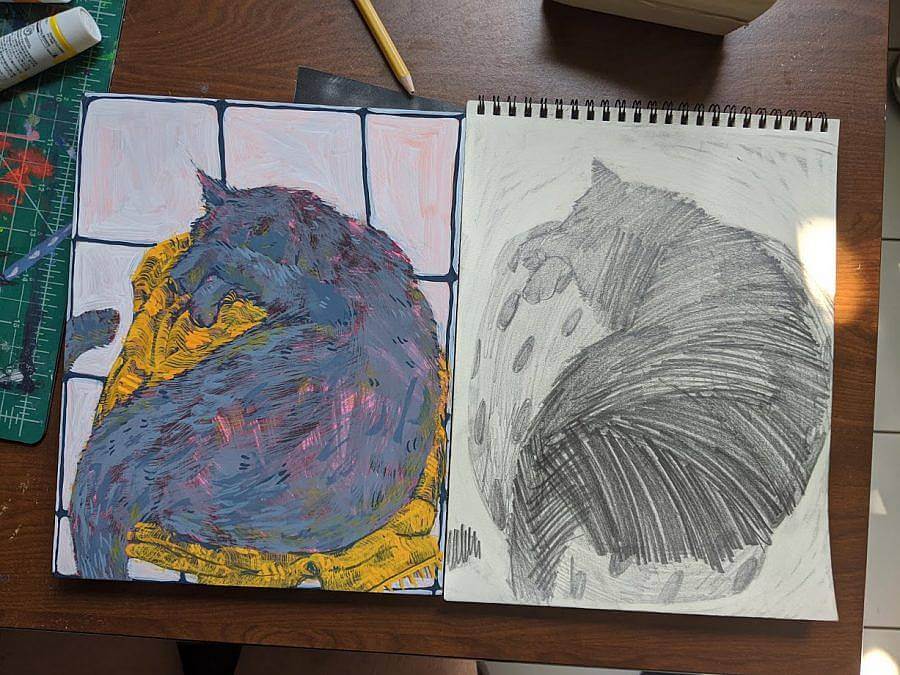

At my apartment in Logan Square, I operate out of a three-season attached porch. It’s big enough to work on 2-3 oil paintings at a time and small enough that it forces me to stay organized. I face a small backyard, and a tree comes up against my windows. I have a large wooden desk, a stainless-steel kitchen cart, both Brown Elephant finds, and an AC Moore wooden easel. Not great, but I’ve tinkered with it a bit so it can hold more weight. (Jamming a screw through its spine.)

My cat, Pickles, joins me on the porch for painting time, but often leaves for the thrills of hunting spiders in the basement. He is one of the hearts of my studio practice. The other hearts, notably, are the awkward flybys I have with my upstairs neighbors coming and going walking the dog. They have seen many a boob painting, heard many a song half-sung, and have adjusted far better than I expected– even better than a few studio mates.

What artists that have influenced you?

Riva Lehrer, Jaya Howey, and Breehan James. All of my friends and colleagues, too many to name.

What motivates you to include, exclude, and cut out parts of the body?

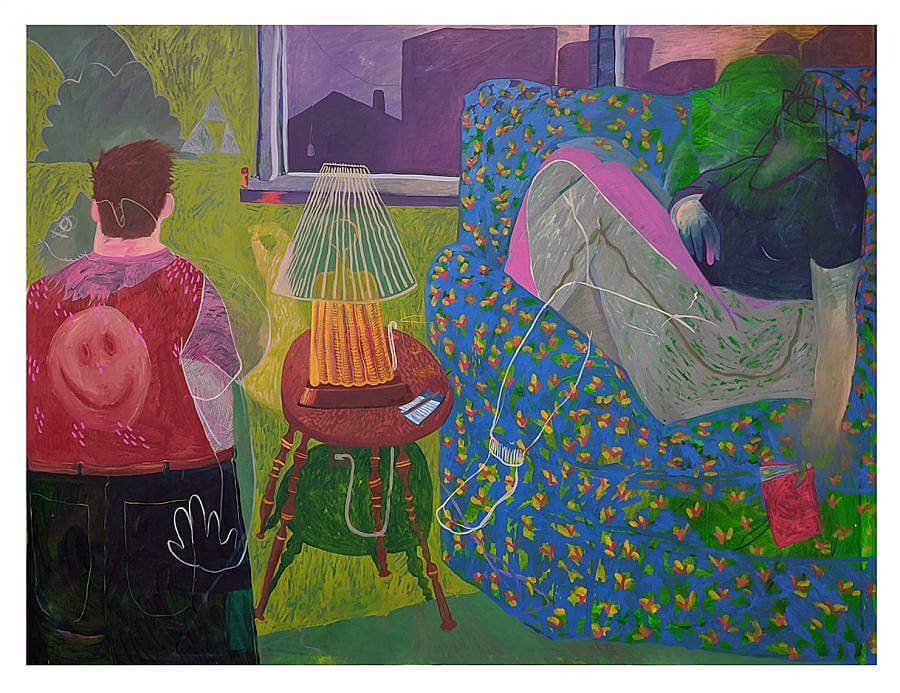

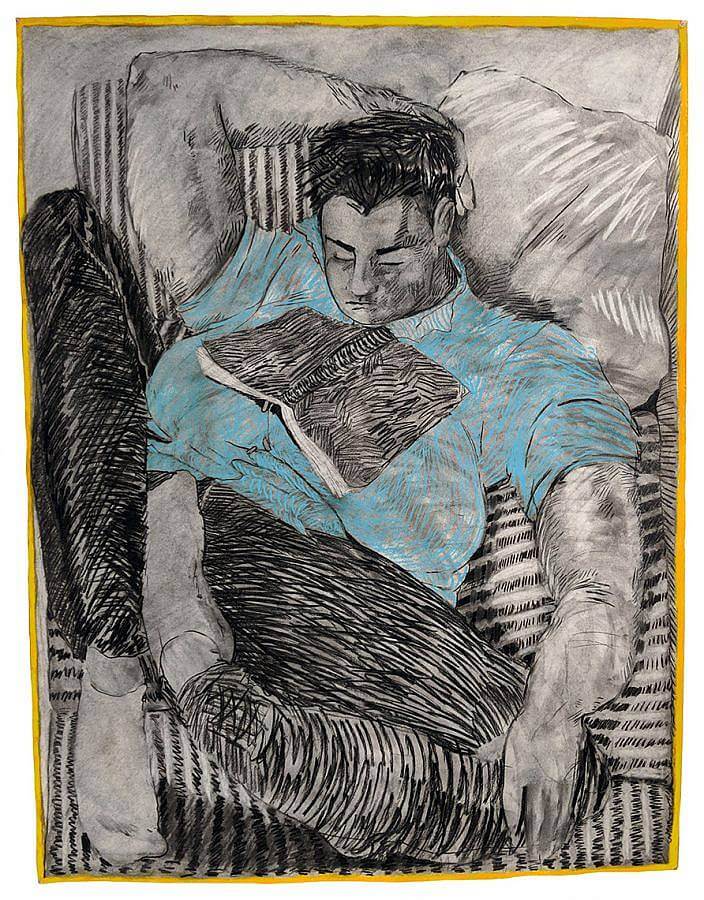

My most pivotal moments in drawing and painting come from collage. Working with my body, or with self-portraiture in general, there’s personal freedom associated with tearing it up and sewing it back together. One of my recent paintings, “What Gives?” more aggressively participates in the opening of my body, performing its malleability.

I’m motivated by the ease of the body in painting. As a part of the trans community, or even the greater queer community — and at that, let’s include most everyone outside of the colonial construct — body modification is a source of power and ownership. Access to your own body is a right not often extended, and the impulse to make changes, perform exorcisms, and to tear yourself up or to neatly cut the body into squares (sorry this sounds so emo), is a beautiful thing to be acted on. Painting gives me the opportunity to explore this.

How I work with my body in painting relates explicitly to how I use the grid. A structure given to me, that in my representation of it can wiggle, can dance, can slip away, or stop following the rules.

How does fallibility relate to your practice?

There is the fallibility of measurement in physical terms and of the gendering and sexing of the body. The erroneous protections of binary, western colonial perspectives on the presentation of gender. Just like the grid can wiggle and change and a line can split into two lines, I pursue growths through the bending and breaking of social or physical expectations of the body, specifically, lately, the “female” body.

What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Octavia Butler’s “Dawn”. 10/10 would recommend, especially without reading any press or reviews of it first. Counterintuitive, I know, but it’s worth it.

Last exhibition you saw that stuck out to you?

Stevie Hanley’s show at M. Leblanc. I’ve been out of the art experience for the last month since I’ve been home, but even from a year ago, Stevie’s drawings and their physio-psychic homo-metabolisms get to me. I wouldn’t say it was the last one to stick out to me, but it sort of visits me in the studio every day. It’s an exhibition that haunts me?

What are some recent, upcoming, or current projects you are working on?

I just wrote a review of Cameron Spratley’s show, 730 at M. Leblanc for the Chicago Artist Writers. Earlier this summer I was a part of three virtual group exhibitions. The first exhibition was So Far, a virtual exhibition held by La Loma Projects about portraits in quarantine. The second, Devil’s Lake, was a virtual exhibition that paired poetry and visual art together as part of the launch of Sarah M. Sala’s book of poetry ” Devil’s Lake.” The third exhibition was a physical and virtual show, Long Hello, curated by Evan Gruzis and Carter Foster for the Green Gallery in Milwaukee.

Recently I’ve been at home, in Sandwich, MA following the death of my mother. The only thing I’ve been painting for some time are the walls of my childhood home. I suppose I thought the grief would push me towards the escape that my work usually promises me, but it, like the pandemic, feels more like a throat and hands bound in cement than any mythologized creative impetus.

Interview composed by Amanda Roach.

Alt-Text by Ruby Jeune Tresch