Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I’m Anna Meredith, I’m a composer, who works in quite a few areas. I come from a very classical background, and I now work across contemporary classic and electronic music. I do some installation work, and write music for film and tv. I’m also playing a set at the Empty Bottle, on March 26th with Holland Andrews.

How did your role as a composer evolve?

I know lots of composers who were writing at a young age. That wasn’t me. The first time I wrote music as a teenager, was working on the music you had to write for school exams. Before that, it was playing. I started learning Scottish fiddle, the recorder, and other little kid instruments. As I got older I started playing clarinet, and I joined lots of youth orchestras and bands, where I learned drums. My way in was lots of playing. I got into grunge music, electronic music, and stuff my friends liked as a teenager. I didn’t focus on writing music till quite late when I went on to study music. I started to hear other people’s music, and feel, “oh wait this should be doing this– I started to have this distinctive feeling of what the music should do.

How do you feel about bringing FIBS to the US so many years later?

We made it over to the US in March 2020, about to do our third US tour. However, every single gig got canceled before we had done the first one. We just had to fly back. It was really sad, and we lost loads of money. The whole of 2020 was a write-off. I’d poured everything into the album, and I wanted to give it the energy it deserved. Now, I definitely take a lot less for granted. It’s never been easy, we’re not mega-famous, or huge. All these tours are a real labor of love and investment. We have to save and pool a lot of money and energy as a team. I feel grateful, and extremely privileged to do this at all.

In terms of my relation to the material. It’s not one of those things where I’m over the material, it still feels fresh to me. I love it. The set has changed, there’s stuff that we weren’t playing, songs from FIBs that weren’t previously on the setlist, that we’ve now worked up now. We’ve also got a few new things from my project Bumps per minute. This tour is a celebration of FIBS and performing the works in-between.

Speaking of performing, there’s a very intentional continuity between yourself and your band. What has inspired the visual aspects of your performance as a band?

We’ve played together for 6+ years. We’re all really close friends. We love playing together, it’s joyful and we get a lot of energy from one another on stage. It’s a lovely thing. We’re all quite communicative musicians with the audience and one another.

In terms of the look, ideally, we’d be working with huge spaces and with huge production budgets. So it’s what we can do to tie things together. The set itself has fast music, and slow music, you know it’s got a lot of variety to it, but it’s all distinctly my music. Lots of the instrumentation is varied, for instance, we’ve got a tuba, cello, electronics, and a guitar. However, I feel that there’s a real homogeneity to it. So we’ve got our outfits, which are all slightly different but allow each person to wear something within that theme. We try to do what we can to give an identity to something, that on the surface, has quite a lot of variety.

Each song on FIBS is another daydream. I’d love to hear a bit about the inspiration behind composing ‘Paramour.’

My starting point is never genre-led. It’s normally quite technical. Like I want something fast, or that has a particular shape. Or I want to write something disjointed, or aggressive. When I’m thinking about the album I step out of it as a whole and think of it as a pie chart. I consider what forms will balance and complement each other. I go in and make the things I think will be good partners together.

I do this thing with any song. I draw, almost like an architectural sketch of the shape of the music. The pacing and momentum is the most important thing for me when I’m composing. Does it change direction, feel, or emphasis, do those shifts feel satisfying or surprising? For everything I do, I draw the shape of music, to have an idea in real-time, when something needs to evolve.

With ‘Parmour’ I wanted to have all this energy that sort of builds. I knew I wanted it to have a half-time, this slow regressive thing at the end. So I worked backward from that so that half-time could feel chunky, huge, and almost sort of shocking. It’s not like this piece is about my ex-boyfriend or something, it’s more so me trying to control and harness energy.

How did you feel making the musical shift from Varmints to FIBS?

In some ways, it’s nice to hear you think they’re different. I believe they are different. On the surface, many people have felt they are similar. Yes. they have songs, they have instrumentals, they have slow things, fast things.

I think the main difference for me is confidence. When I listen to a FIBS performance now, which I still love, I don’t feel ashamed of it or anything. but I hear that technically my production skills have gotten better. There’s more weight to it, FIBS. I think Varmints felt like such a real shot in the dark, in terms of this is something I want to do. I didn’t know if it had any momentum or if it could live in and of itself. It’s not like I’m some massive name, but it’s managed to become part of my working life. I think FIBS was written with greater confidence.

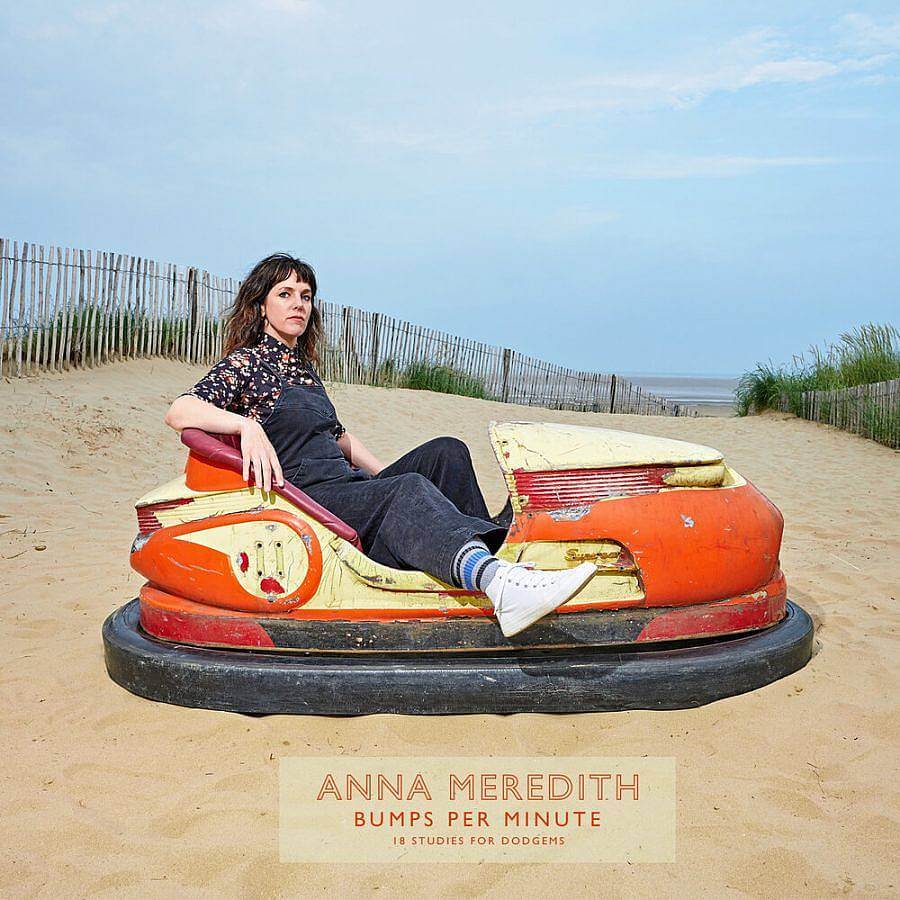

How did the Bumps-Per-Minute Project come about?

The idea for the piece came about because my studio in London is in a complex with this big old building that has a courtyard in the middle. In the winter there’s an ice rink. I was talking to the program manager because they were thinking they were going to have to cancel skating due to covid. I had this light bulb moment! In the UK we call them dodgems, but bumper cars. You could distance them, and clean them, and it could be outside.

I thought that at the same time, this would be a great moment, to have a transparent playful installation piece. There was a pendulum in the footwell of each dodgems, that depending on how hard you hit another car, triggered a piece of music. When people smashed into each other a new track was triggered. Musically that was interesting to write.

I’m not necessarily thinking about people shuffling through the tracks in an album. For the installation, I tried to think of 18 different bits of music that would have no vocals, no real instruments at all, just synths, no beats. Almost like studies, piano studies. I did my little shapes thing, and the shapes themselves were sort of redundant because I wouldn’t have control over how much material someone would hear.

I imagined it as 18 new doors being flung open at the same time. When you meet each new person you need them to be as confident and layered and ballsy as possible to dominate space. They’re all very fully formed. I liked the material a lot and made an album version and an online 8-bit installation at bumpsperminute.com. The album versions are slightly more developed. I feel that the album is an artifact of that installation. Now that we have the mechanism, could do it again with some other dodgems and I hope to explore it again.

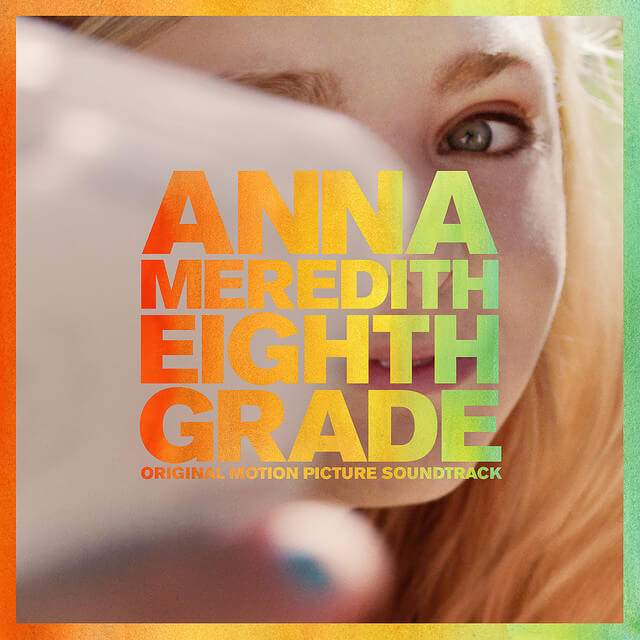

Can you talk about the approach you took while composing the soundtrack for 8th grade ?

I was given a lot of space, It was great, the music is loud, it’s upfront a lot in the film. It was the first soundtrack I’d done, and I appreciate now how rare it is to be given that much space. I think I was lucky that Bo’s approach in making the film was that he wanted the music to feel real and tense and anxious. He wanted the teenage anxieties that were as real for her, as defusing a bomb for someone else. To not step back from her, to not cutefy it, or add a layer of distance to her feelings, but to help the film be plunged into whatever nightmarish teenage situation she was in. I took her seriously and gave her as much weight as I could. It was great and a lot of fun to do.

What are your upcoming plans?

The plan for this year is to work on a new album. I imagine on the surface, they’ll be similar things, lots of fast things, slow things, loud things, quiet things, stuff with energy. That’s just how I write and I’m not going to change how I write. I do think there’s stuff I’ve reflected on over the last couple of years that I feel angry and frustrated by. I like music to be joyful and to have positivity in it, but I think there will be some stuff about bleakness and helplessness, that still has a balance to it. Those aren’t subjects that I’ve focused on compositionally before.

Interview conducted and composed by Joan Roach. Portrait of the artist courtesy of Pitch Perfect Press.