Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I am the Director of External Relations for Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, one of the first and largest centers for artists with developmental disabilities in the world. I was hired in 1999 as Executive Director, and after 20 years, have recently transitioned into a role more focused on external constituencies, than internal operations. The center was formed in 1974 by artists with a (then) radical vision to have newly de-institutionalized people with disabilities have a place where they could grow artistically, exhibit their work, form a community, and have a link with the general public. This was not a commonplace concept at the time. We routinely serve over 150 artists per week in our industrial building that includes work areas for all the visual arts and a gallery. We are proud to have helped some of our artists achieve great contemporary success with exhibitions worldwide and to have artists included in major collections including MoMa NY and San Francisco, the Pompidou in Paris, and numerous others.

Where do you believe art and advocacy meet?

For me, when they intersect, they don’t really meet as much as collide. I feel that there are fewer artists doing political work right now than I might hope for, but historically when work has a strong advocacy role it’s integral to the work and you can’t separate it out because it forms both the form and content of a work of art.

How did your interest in art begin? Advocacy?

I went to art school, thanks to Cindy Sherman! She and Robert Longo started a community photography darkroom in Buffalo, New York, where they went to art school, and where I grew up. I started taking photographs with my father’s old camera and wanted to learn how to process film so I stumbled into the darkroom one afternoon on my way home from high school and was hooked. This was in the late 1970s when all the industries in Buffalo had collapsed, and there were no jobs. I had been destined to get a job in a steel factory or similar, but instead, I got a scholarship to go to art school at the Rochester Institute of Technology. I also lived near the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo which has an amazing modern collection and it opened up a whole other world for me — different from the urban working-class immigrant one in which I lived. There was this entire other world out there that seemed so ordered and modern in contrast to my life, and I wanted to discover it.

After graduate school (MFA, from MICA,) I was teaching photography at American University in Washington DC when my friends started dying from AIDS. That led me to work on a national tour of the first documentary films about AIDS, and art and advocacy collided for me in powerful ways. I moved to San Francisco when I was offered the job of Executive Director of the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, during a time of the new Queer Wave cinema, and assaults on queer images by the right-wing furthered my activism in the art world. We premiered the film “Paris is Burning” and the house came down as a new kind of LGBTQ community was forming around ACT-UP, Queer Nation, and a post-AIDS reality. I remember hanging out with Todd Haynes in the lobby of the Castro Theater, getting him a slice of pizza as he paced during the screening of his new film “Poison,” which as we were premiering at the time, and with Rob Epstein and Jeffery Friedman during their film “Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt,” which went on to win an Academy Award.

How has your background in film and video influenced how you see artwork today?

I think a background in photography makes you visually aware, but also less tied to a traditional notion of what art can be. Photography was not considered a real art form for so long that it kind of parallels the history of “outsider art.” Photography freed painters to do whatever they wanted…not be tied to representing nature, but then it took time for photography to be seen not merely as a way to record the world, but to interpret it as well. For me, there is freedom when art does not have to be academically based or related to art history. “Outsider” work has always come from the artists first, not really from the galleries or museums, but then collectors and exhibitors try to scramble and catch up. There are some similar lessons there I think.

While there are often mixed feelings around the term “outsider” when it comes to artists with disabilities what do you think the significance is in the label and do you foresee the term sticking around?

For people with disabilities who have been marginalized for much of their lives, a label like outsider does not help. I see Creative Growth artists as being exciting contributors to the contemporary art world. Words like ‘outsider’ can be helpful if they open our eyes to the fact that art can come from anywhere, but not as a word that labels a particular group of people. I think the word will continue to be used since nobody has come up with a better one yet. But mainly I just say contemporary, or sometimes self-taught when discussing our artists.

What do you feel are some of the biggest obstacles the art world has to overcome in terms of ableism?

So much in the art world revolves around access and whom you know. I think that since people with disabilities are so often pushed to the sidelines, they are often not part of the conversation about who the artists of our time are, and less likely to be a part of the gallery scene. And they often lack resources that allow them to bring their work to the public. The system of art schools, galleries, collecting, and marketing is complicated and difficult to access, more so if you are marginalized in society as well. So I think this adds to the obstacles for artists with disabilities. You see this with work by black artists and women artists….that is now just being “discovered.” Well, it’s been there all along…you just weren’t looking.

Can you share one of your happiest moments from the past year?

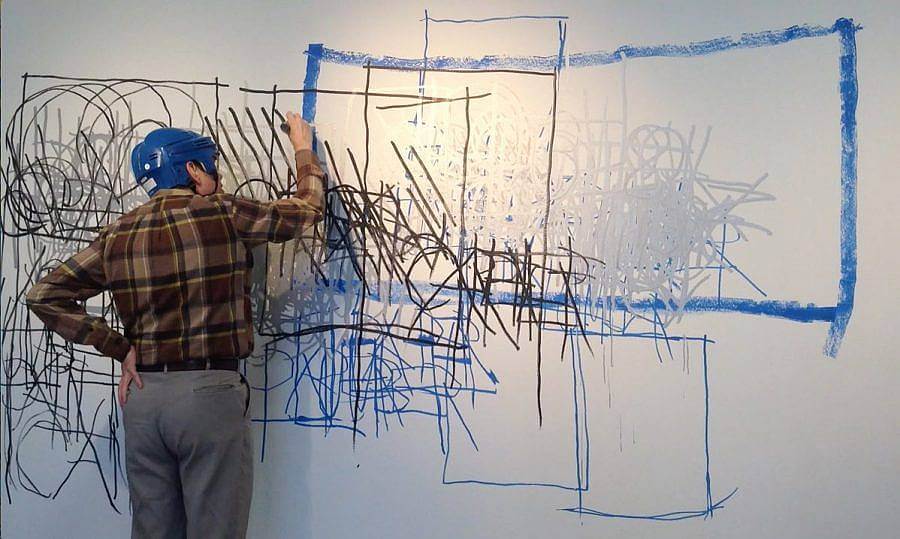

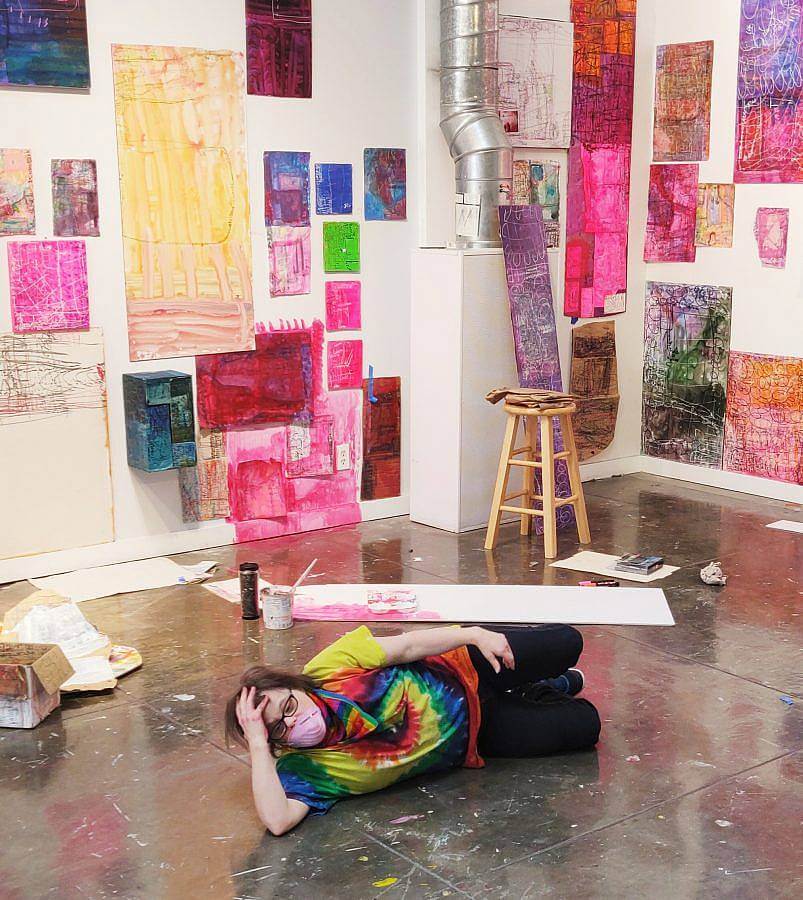

The happiest moment could include watching Nicole Storm install her exhibit at CG when we able to present our first exhibit of the year. She was handed the gallery to do a site-specific installation while we were closed, and her energy and artistic presence during a horrible year was a reminder of the power of art to help us transcend difficult times.

What was the first piece of artwork you remember buying?

The first piece I remember buying is a photograph by Philippe Halsman of Salvador Dali underwater spitting out milk to make it look like an atomic bomb just went off. I bought it for myself as a gift for my high school graduation with the money I had saved for college. I think it cost about $100 and that was more money than I ever thought was possible to spend on something that wasn’t food or rent.

Can you talk a bit about your history with Creative Growth, having been the director there for around 21 years now?

When I was hired, the goal was to advance the artists and their work into the contemporary art world and further push for integration and leadership in the international art scene. Judith Scott was working at Creative Growth and her work became a symbol of how work by a woman with Downs Syndrome could cross over in the contemporary art world. It took years of showing her work to curators, museums, collectors before she became an overnight sensation, but she helped pave the way for many others since.

Creative Growth became the first non-profit of its kind to start to participate in art fairs, and I think that was also a major turning point in bringing our work to the attention of collectors and curators. This led, over time, to CG artists being included in major collections, the Venice Biennale, etc. I think people take it for granted now…but the field has had enormous advancements in the last 10 or more years.

How have you been navigating the pandemic, as the director of Creative Growth, and more broadly as an arts professional?

I wish I could say something very positive, but it’s been extremely hard on our artists and staff, and it gets harder every day. For the most part, CG artists have often been home-bound and on the sidelines of society, but to now deny them the community that they have finally found in our studio is particularly heartbreaking. Of course, we are doing remote classes, and bringing people art supplies, and staying in touch but as we approach a full year of being closed it just gets harder and harder. I don’t think anybody knows how this will impact our community overall when we come back together. Hopefully, we will be stronger for enduring this. Organizationally we’ve not been able to participate in all the international art fairs where we meet so many collectors from around the world… and that’s been an impact on our presence in the art world as well. I miss everybody and am so sad that this is happening like we all are. And I’m reminded of my early work around AIDS and the frustrations and anger that come from the politics around public health and the similarities are very, very disturbing.

What have been some of your favorite programming initiatives that you’ve taken part in, or organized at Creative Growth?

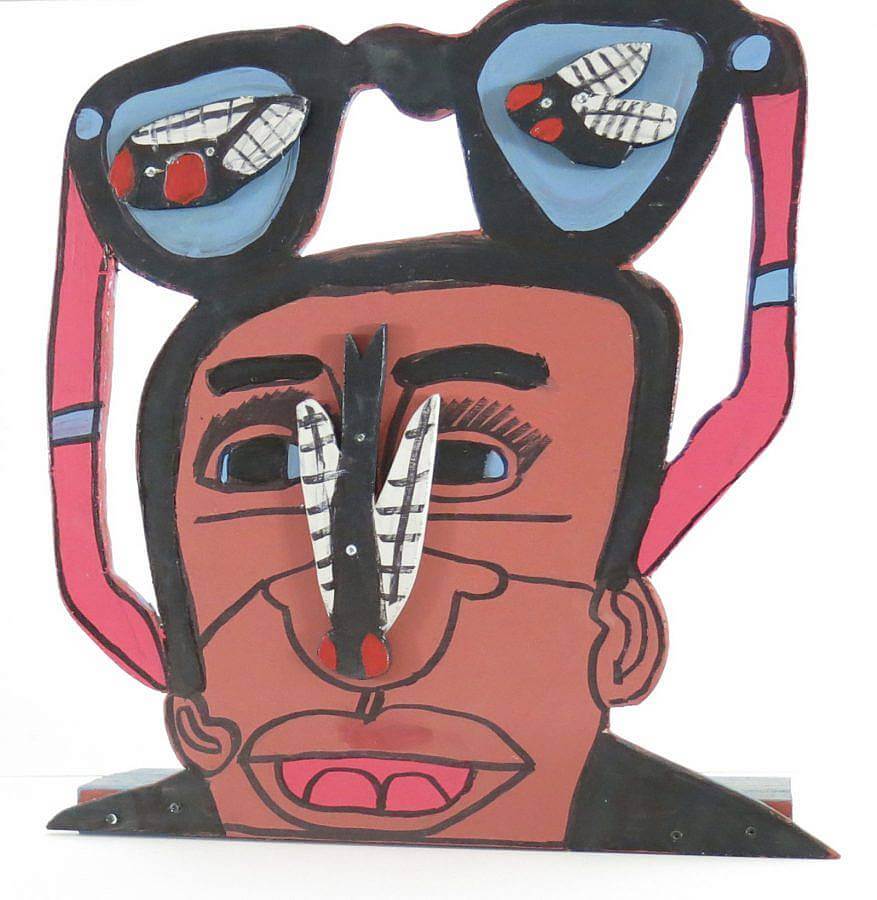

I liked an exhibit of Dan Miller and William Scott in our gallery that I co-curated with Catherine Nguyen. Art Forum named it as a notable exhibition of the year, and it was just so clean and modern! I also was proud of the early Judith Scott exhibitions that I helped organize in Tokyo, Lausanne, New York, and finally at the Venice Biennale. Seeing her work in Venice, next to Creative Growth’s Dan Miller was very moving for me. You could sort of hear the glass ceiling breaking as their work dominated the final large viewing room of the exhibit hall in Venice. I’m also proud to have produced two international symposia for art and disability professionals around the world. The network and collegial support formed there have been very useful as centers around the world grapple with the pandemic and program closures.

What artists should we be aware of?

In music, I can’t stop listening to Kenny Hoopla. He’s a pretty amazing blend of young energy, rap, rock… He relates to modern recording artists like Lorde as well, but also to contemporary urban music with a style, that is urgent, compelling, and political. “I was born with a target on my head,” he sings like a young black man in America today. I think he also reminds us that black artists have been an overlooked part of so much contemporary music, not just rap and R & B, including significant contributions to rock and other genres.

At Creative Growth, I’m really drawn to the work of Ying Ge Zhou, Ron Veasey, and John Martin. You can see examples on our website.

Do you have any upcoming projects?

Yes, I’m working on a major retrospective of the work of Creative Growth as an organization that I can’t announce yet but hopefully will come together in 2022 at a Mid-western museum. Also, a major retrospective on William Scott in London at the end of the year as well.

You’ve once said when talking with Dystopian hosts Jill Van and Christopher Smit, that everybody can be an artist, how do you feel you fulfill that role in your life?

I am no longer a working artist, so that’s interesting, but I think supporting artists and having the creative freedom to represent them is more nourishing than exhibiting my own work. I won the Best Short Film and Most Promising New Director Awards at the Sundance Film Festival in the late 1990s and immediately stopped making art. For me, there was always a personal side to my work, as there is for many artists, and I think that was something I didn’t want anymore. But to be able to channel that same creative energy into supporting the work of other artists…not just in exhibitions but also in affording them an opportunity to become established artists is a pretty good testament to the power within each of us to find our way forward through creative expression.