Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I am a Korean-American writer, artist, musician, and astrologer who was raised in Los Angeles by a family of witches, and now I live between L.A. and Berlin. I’m queer and use they/them pronouns, and I identify as disabled, particularly as crip. I think of what I do as writing, no matter the genre because I work with the definition of writing as language embodied. For me, this means that words on a page, screaming in a room, and dragging a hand through water are all different kinds of writing. Some of the obsessions and devotions that find expression in my work have to do with mystical states of fury and ecstasy, doom as a liberatory condition, the radical permeabilities of the body, deviant forms of knowledge, and the politics of care.

How did you get started as a writer and performer?

I knew from very early, like kindergarten, that I wanted to be a writer. For something like 20 years I’ve written 500 words a day as soon as I wake up, and it’s the craft I feel most in service to, most articulated by. With music, it was in my DNA and all over the house growing up. My dad is a musician and taught me to play the guitar when I was 12. Lol, I immediately wrote enough songs for a record that we recorded in my bedroom, and then spent the next decade in bands, self-releasing four records that I really hope have all disappeared by now. Then I didn’t play music at all for a decade—that’s a long story, maybe it involved a really slow exorcism—then came back to it when I was 32. It’s sorcerous, music, it’s in the blood—I hadn’t touched a guitar in ten years and when I picked one up again, it was all there. My body just knew.

Your newest album, Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House, was written in part for your late mother (a Pisces). The album’s title is an astrological placement, what does its name tell us about the album?

One theory of the asteroid Black Moon Lilith is that it represents the place where you will be most damaged by patriarchal violence, and therefore can be the place where you are most liberated from patriarchal violence. It’s a sort of a crucible of pain and deliverance from that pain, but the exact source of that pain, like, whose it is, is a conundrum, an ouroboros. Mine is conjunct my mother’s sun. My mother was mythical and monstrous. She was my Medusa. I have been most damaged by her of anyone but also most forged. Sorry, it’s hard for me to talk about.

Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th house, apprised by Korean shamanist ritual and Korean tradition of P’ansori, centers on the act of performance. Can you talk about its emphasis on performance and mysticism?

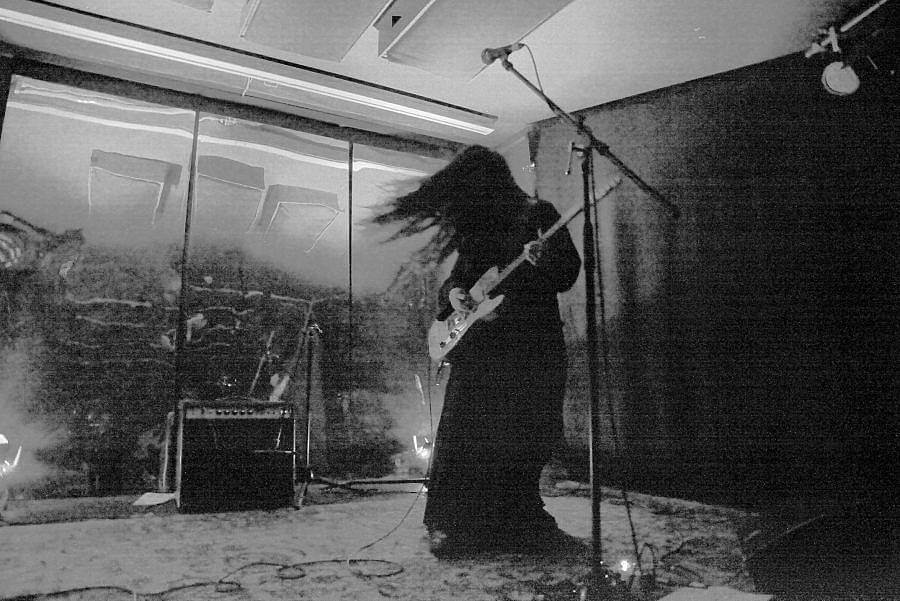

Black Moon happened first as a live performance, rather than a record, because the only thing I could do in the wake of my mother’s death, was make these sounds in my throat and play the guitar with this brutality that made me ache in a way that felt good, and I’d just do it for hours and hours and hours alone in a room. I’d just violate the guitar and shred my throat until I couldn’t stand anymore. The songs emerged from this pool of deep time and cosmic pain and at some point, I realized that the performance, when it was really cooking, was nebulizing me, it was pure annihilation. P’ansori values the voice at its most ravaged, it centers the grit and age in the voice, the body that houses the voice and what it’s been through, which is a sort of antithesis to the Western aesthetic of having the voice be clear as a bell (like in opera).

When I started to tour it, the performances became this grief ritual through the communion with the audience. I’d try to bring my mother’s ghost into the room, and I couldn’t do it alone. She’d arrive at some point. I’d hear people in the audience crying. Some came up to tell me afterward that they could feel the exact moment when she was there.

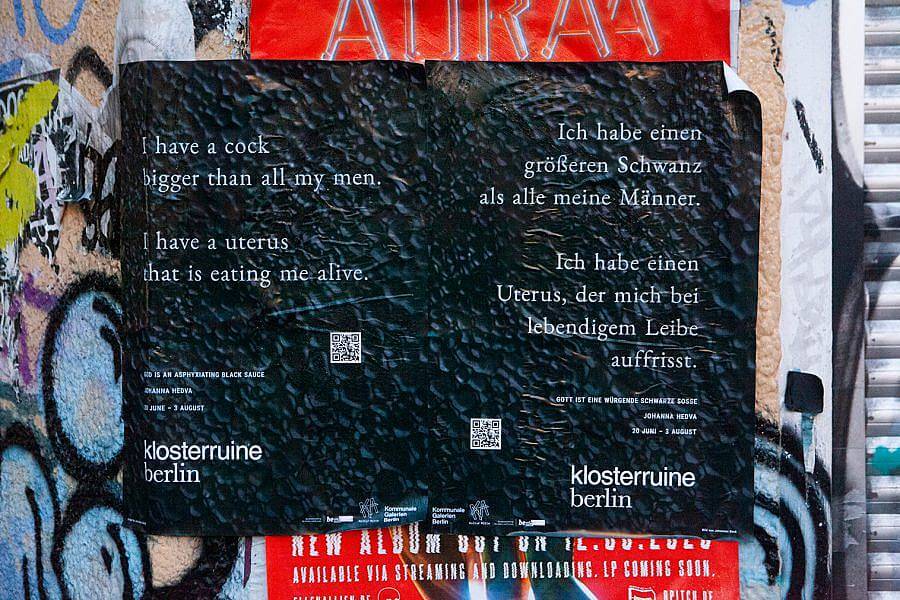

Your multi-media exhibition, God Is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce , held at the Klosterruine, Berlin, featured your work, “A Playlist to the Void.” In what ways does this work represent your mystic multidisciplinary practice?

The “Playlist to the Void” collected my two recent albums, The Sun and the Moon and Black Moon Lilith, with my reading my new book, Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, as well as a track each from four brilliant musicians who I’m lucky to call friends: Geneva Skeen, William Fowler Collins, AM Kangiesser, and Gabie Strong & Pauline Lay. The “Playlist” played continuously for six weeks in the ruins of a 13th-century monastery in the center of Berlin, and there was a website with a Livestream of the sky over the ruins, where the entire Playlist was accessible for free. It was happening during the pandemic, so I wanted the show to be about matters of accessibility as the very condition of absence(s) and nothingness; I began with the condition that most people would probably not experience the show with their corporal bodies in the actual site. But troubling the absence/presence binary was at the heart of it. It was an exhibition made for ruins and the ghosts who lived there, which foregrounded the sky as the primary visual, and made a bed for the communion of voices, sound, music, and noise with emptiness—it proposed that there’s no such thing as absence, not really.

In conversation with Dan Bustillo about your 2018 novel, On Hell, you cite the book and your work as attempts to cope with and understand how “different regimes of power are embodied, how they soak into our cells and invade our bodies and become part of our materiality, usually without our permission.” How do you relate this to your work?

I’m haunted by the relationship between ideology and materiality, like, the horror of how the former infests the latter. It’s a kind of body horror to me. For example, to see how our society is structured by white supremacy, say, is its own kind of horror—but to be alerted to your own internalized white supremacy is another, more insidious kind. I think that we are all washed and bathed and soaked and saturated in the ideologies of oppression—racism, ableism, patriarchy, homo- and transphobia, etc.—to such an extent that these are in us on a material level. Like, “it’s coming from inside the house!” To me, this is the root that has to be dug up. It’s not only external, all of these problems “out there”—it’s internal, which is to say, it’s part of our beings and bodies.

Do you have any upcoming projects or shows?

Welp, I’ve fallen in an AI hole, and am working on a project with an AI clone of my voice, that speaks a language that I’ve created through divination techniques, braiding together the text corpora of mystics writing about the void, physicists writing about dark matter and energy, and my amazon.com account. I’m very excited by the proposal that divination is a form of AI that predates the computer. As a sound piece, the voice will be situated within a physical installation sort of like an infinity/void room (like the black room in Under the Skin), but I’m most excited about making the online iteration. I’m imagining an immersive experience with a vibe similar to the videogame P.T., but in non-Euclidean geometric space, that feels like you’re in tar but somehow weightless. I want it to be a superabundance of nothing. It will come out this year.

What are you reading right now?

This is my favorite question to be asked ever!

I am a new devotee of Mariana Enriquez, an Argentine writer who uses supernatural horror to make a blistering political critique. My skin turned inside out reading her short story collection Things We Lost in the Fire, and her latest book of stories, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, is taking me apart.

I also just learned of Hilda Hilst, a 20th-century Brazilian writer. I’m reading her novel With My Dog-Eyes, which is about a mathematician who is trying to find the equation for God, like, um, genius.

And I’m really excited by two works in Black critical theory: Zakiyyah Iman Jackson’s new book Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Anti-Black World and Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology by Michelle M. Wright.

Can you introduce us to your recent book, Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, 2020

Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain is a collection of a decade of work. She’s a shapeshifter: the texts of her are poems, essays, performances, plays, an encyclopedia, autohagiography. Minerva was never born as a book—at some point halfway through this last decade, I started collecting works I had made that seemed to share DNA, but over the years, the book as a book kept mutating and transforming in ways that always confused me. It’s a document of sleeping, of fury, of nocturnal and dissolving selves, of the many ways the body is both penetrated and penetrating. If there is a main character, it’s the city of Los Angeles. If there’s a main theme, it’s maybe that motherhood is monstrous, but I don’t think there’s only one theme.

My publisher, Vivian Sming of Sming Sming, and I spent a lot of time together on the design. The materiality of the book is as important as the text itself, and in many ways, I don’t think these are separate. The body of the texts, their face, and skin, is also marrow and spine. A dear old friend, the artist Isabelle Albuquerque, illustrated the cover, and each chapter features one of her drawings. She made all these fantastic, thaumaturgical bodies that are animal and human, both and more. When she sent the drawings, the only editorial note I had was, “Can you please add cocks? Like, really big ones?”

What role does mysticism play in your work?

Music, to me, is one of the most mystical acts because it’s this fundamental paradox where you can feel the edges of your body as they are being annihilated by, and into, something greater than you, which is one of my working definitions of mysticism. I wrote about this at (ridiculous) length in my hagiographical essay on Nine Inch Nails and Robin Finck, and in a piece, called “The Mysticism of Mosh Pits, Or, The Mess of Sociality, Or, Have You Ever Seen Lightning Bolt Live?”—both of which are from a book I’m currently writing called The Mess, where I’m trying to write about what are, for me, the two hardest things to write about: music and mysticism.

I think mysticism is a practice of devotion, and there are different ways one can express such devotion. One way is to surrender to it, to be dissolved by and into it, and that’s what happens to me in music. Another is the labor of devotion, the work, the ritual, the daily tending, the care. The etymology of vigil is “to watch, to be watchful and awake.” Writing for me is this kind of devotion. Sitting down at my desk every morning, before speaking or eating, in silence, and writing 500 words. My aim has only ever been to be a devoted student to my craft, and in this way, I find a mysticism according to that definition of being right at this place where the edges of my body are annihilated into something greater than me. I’m kneeling at the feet of the sentence, you know?

Interview composed and edited by Amanda Roach.