Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

Hi! My name is Sidney (she/her/hers). I am a sculptor based in Pittsburgh, PA, as well as a professor at Penn State University in State College, PA.

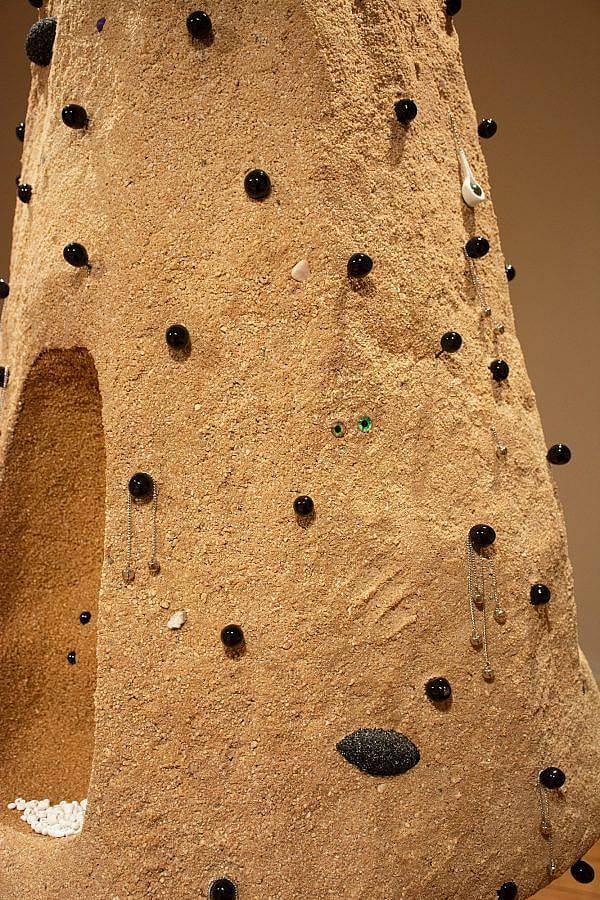

Right now, I am building a ceremonial landscape that is the resurrection space for my childhood self. As an adult, I have become preoccupied with those childhood selves that came before. Where did they go? How do we mourn them? And now, why do we speak about my inner child as if she is sometimes there? Can I keep her?

I’ve been building this sculptural landscape—a make-believe forest—to find where childhood selves go in adulthood and if it is possible to bring them back. The space is playful and dark as I remember both wonderful and terrifying aspects of growing up.

How does your training in dance inform your practice?

I danced for 14 years growing up, performing countless characters. A schoolgirl, a hunter, a cowgirl, a fairy, a flower queen, a dead lover, an evil stepsister, and so on. There was always a right way to be performing these roles. It was the steps you performed and how you performed them, as well as the big smile you donned to hide the heavy up-and-down panting of your breathing chest. As a result, I became sensitive to how the body is given certain roles to perform in dance and in the choreographies of our daily life. I became very aware of the narrow range in which bodies can move safely and without scrutiny both on and off stage.

When I was introduced to sculpture in college, I was told that it engages all 360 degrees of space. This, for me, is dance. Now with my objects and how they are positioned in space, I get to build potential choreographies for the gallery goer. I build paths for movement in and around my work that have nothing to do with rightness. I am still seduced by the potential of my materials and how my objects might influence how a body moves and feels through my spaces.

So many of your works feel like animated, macabre critters. What imagery are you most inspired by when sketching out new forms?

I am inspired by TV and movies from my childhood. Beetlejuice, Aaahh!!! Real Monsters, Rugrats, The Big Comfy Couch, Mars Attacks! I really enjoy looking at anything odd, mysterious, and downright magical. Those magical things might be the dead-looking plants in Joshua Tree National Park that are actually very alive or the violet sea snail which lives its entire life upside down in the sea on a “raft” of its own air bubbles. There are so many things of this world that seem totally unreal. This can be overwhelmingly wonderful or utterly terrifying or both. I keep these feelings close while making in studio.

With these commemorations of youth and their relation to the construction of self, can you speak more on this memorialization of childhood in your sculptures?

This make-believe forest helps me remember and revive childhood. Within it I’ve made a shrine for my pocketed youth (youth that feels like it’s lost in a pocket) and an altar to resurrect my seven-year-old self. These are more direct examples of commemorative forms for youth. A more subtle example would be the votive candle of this ceremonial space: the pasta candle. I fill dry rigatoni and manicotti with wax and wick and put them on and around some of my sculptures. Macaroni was one of the first art materials I used in an elementary art class and it continues to be both a humble and impressive material used in kids crafts. I use the dry pasta as a candle to playfully reengage in macaroni art in a way that also results in a ceremonial object.

What role does time play in your process? How long does it take you to construct your shrines, altars and worlds?

Longer than I’d like. I get really excited starting and finishing a piece. The beginning is often material collecting and armature building. The ending is usually attaching small additions of dangling sand balls, wood hearts, star bracelets and the like. The middle process has become intense and physically grueling. The middle can look like applying sand to forms for weeks on end or making paper pulp by hand. The process slips in and out of intimate, meditative qualities, but I am pretty hard on myself to finish up. Still, I do not expedite the slow processes. There is something really special about that transference of energy, touch, and intimacy with the work. It feels like my effort and time literally grows the work. Grows the forest. Pore by pore, leaf by leaf.

To give you a more specific timeline though, I built the work for my last show from May to November 2020. Roughly 7 months.

Can you share more about the link between conceptual and material preservation in your practice?

An example of conceptual and material preservation in my practice is the teddy candle. They are made from secondhand teddies (or teddies that others did not want) and placed upside down on their heads, solidified and preserved in drippy white candle wax. I use teddybears because they are one of the most known symbols for childhood. My teddy, Bearly, was the first object (or soft sculpture, if you will) I knew I loved as a child. The wax casing is an attempt to preserve the material form of the teddies and the notion of childhood within them. However, the wicks extending from their feet and hands show that they won’t last if they are lit. Do you preserve the teddy or light the candle? The object contains both options, but the wicks offer a choice. Do you keep or let go?

As a teaching artist, what have you learned about yourself and practice through teaching?

I teach a variety of courses at Penn State University (main campus) ranging from sculpture to art writing intensives to advanced seminars. My teaching is not about me, but what I can give to my students who are already very inspiring and hungry to build their own inquiries and trajectories. I’ve learned that three of the best feelings from teaching are 1) building knowledge together as a group through class discussions, 2) helping a student understand something core to their practice through sharing observations and questions, and 3) being the most supportive cheerleader I can be. And, usually the things I share with them, I have to remind myself in studio. Give yourself permission to take up space. Assuage doubt. Take the risk. Ask the hard question. Be flexible. Adapt. Ask for help. Take a break. Give back.

Can you talk more about the process of acquiring the gravestone dust?

The day I collected the gravestone dust is still one of my favorites. I was beginning to make a collection of spiky, lavender trees and had collected a bunch of rocks from a friend’s backyard to become their bases. I was trying to find an easier way to bore holes into them that could hold the spiky dowels securely and support the weight of the mosaic-covered styrofoam containers. I realized a gravestone carver might be able to help me and this took me to Mayes Memorials, a family-run business since 1880, in State College, PA!

Storytime:

I drove up to the storefront and approached the door with three sizable rocks in my arms already nervous about how to ask my question. As I entered, I saw a man helping a couple design a headstone. Feeling immediately inappropriate, I wavered at the door contemplating if I should just leave. The man noticed me and asked brightly how he might help me. I asked if he could drill 1-inch holes into my rocks about 1-inch deep. He said sure and asked me to leave the rocks by the door and come back by end of day.

Upon returning, the store was vacant making me feel less like a nuisance. I did not want to be burdensome with my bogus requests while families were actively mourning loss and designing memorials. The man let me know that he broke all my rocks under the pressure of the equipment. This was fine although now I had to collect more rocks. We started chatting. We slowly got to talking about sculpture realizing the overlap between gravestone carving and object making. He pointed to his shelf where there was a grey Nittany Lion—the mascot for Penn State—with its paw draped over the edge of the shelf as if it was alive. He told me that had been cast from their gravestone dust. Now he was talking my language.

This lead to an amazing tour of their facility with an impeccable dust collection system that dumped all their dust into a deep, metal container. This dust was like a fine grey talcum powder, yet it was essentially the carved names and dates of people who had passed. I met another carver there who also carved porcelain teeth for a living. Everyone there seemed to make work surrounding loss, whether it be loss of life or tooth. The most poetic, heartfelt part is that they told me the dust is like lime and they use it as fertilizer on their grounds. Now the names were not just dust, but fertilizer. We’ve come full circle. Death producing life.

I was completely awestruck by the whole experience. I was told I could come back and collect as much dust as I wanted. I scurried away to buy 3 huge lidded buckets and sprinted back to the facility. After shoveling gallons of dust and struggling to get them into my car, I thanked them again and again for their openness, brightness and generosity. I was so concerned that I was being insensitive toward their daily business with my rocks. Instead they were unbelievably kind and helpful. As I got back in the car to drive away, Billy Joel’s Only the Good Die Young played on the radio.

How do you use touch and intimacy in your sculptures to reflect on memories of childhood?

Childhood is rife with touch and intimacy. Children learn through touch. Babies want to put most things in their mouth. Youngsters (aka love objects) are regularly hugged and coddled by family, friends, and neighbors. This instinct toward touch and closeness is slowly tamed out of them. In adolescence, something shifts. You start to become sexualized. Touch and intimacy are now reserved for those you have crushes on. You don’t hold hands anymore with your best bud. Now you whine when you have to give your parent a hug in public. (Heck, free hugs are now social experiments intended to go viral on the Internet). As you get older, more and more space is put between you and other people.

Touch and closeness and intimacy live in my work and practice. My hands are all over my sculptures and I spend countless hours with them responding to their needs. Technically, my hand is often visible in the works’ surfaces. Formally, the work has waving, reaching, growing and protruding forms. The work wants to engage with you, maybe even touch you or tempt you with their surface. They are built to draw you in, closer.

I am obsessed with these things in my work and studio. I want them to exist in an unadulterated way. Yet, I also include when they start to shift toward that sexual line. When it starts to get confusing. When you don’t hold hands anymore with your best bud, but you don’t know why.

Interview composed by Kaitlyn Albrecht, Ruby Jeune-Tresch, & Joan Roach. Edited by Kaitlyn Albrecht.