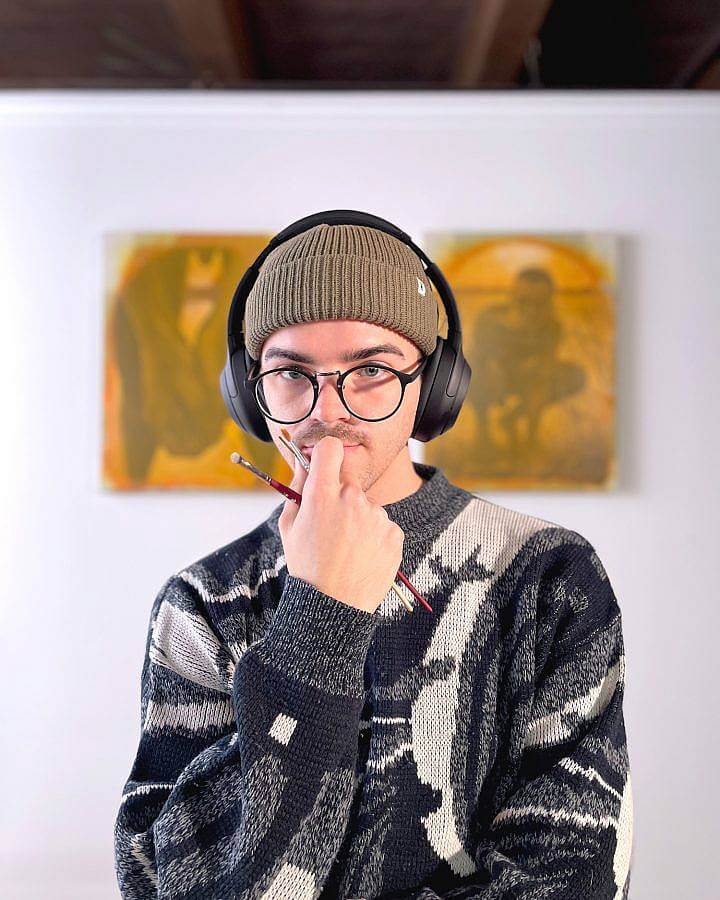

Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do

I was raised in rural Wisconsin – most of my early years were spent in the “Northwoods” region of the state. My upbringing was largely bedecked by iconic Americana artists such as Norman Rockwell, Thomas Kinkade and Terry Redlin, who now inform the visual language in my work. I look to artists like Grant Wood and J.C. Leyendecker as primary historical influences. Researching my uncle and namesake, Martin Ross McRoberts–who was himself a queer artist–has become my link and portal to an increasingly fading queer past. I consider my work in conversation with contemporaries such as Jacob Todd Broussard, Jordan Ramsey Ismaiel, Matt Lifson, and Pacifico Silano.

Beyond my studio practice I love to spend time with my partner, Nate, and our thirteen year-old Boston Terrier, Bug. On weekend mornings we go for pokey walks to the coffee shop and usually split a breakfast sweet.

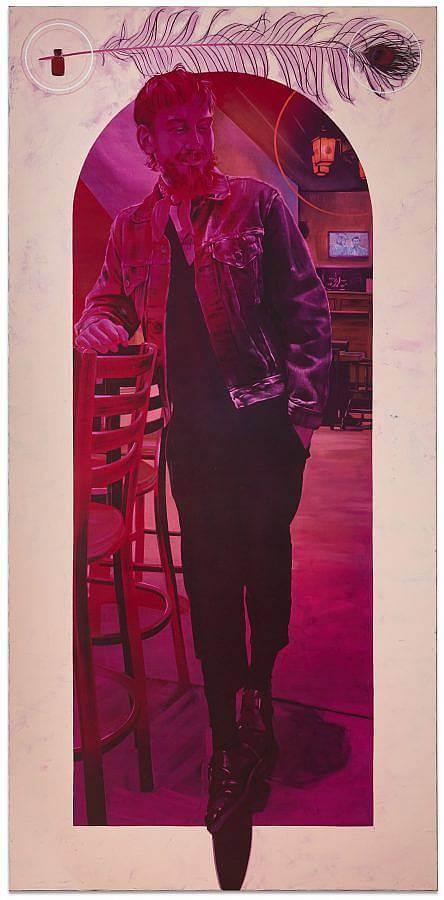

Image by Ian Vecchiotti. Courtesy of the artist and The Valley, Taos.

How did you get into painting?

The short answer is, in the Fall of 2020, I leaned into oil painting during my third year of graduate school as I prepared the works for my thesis exhibition. I had been working mostly in drawing and watercolor mediums prior.

The complicated answer is that I’ve always been a painter but I didn’t recognize my work as painting. Throughout my education I’ve actually always felt a bit averse to being labeled as a “painter.” There are a number of reasons, but the primary being that I didn’t feel awake and aware within the canonical world of painting. In my painting seminars, I was always fighting against the medium and I didn’t always understand the language and references my peers were pulling. Paintings didn’t really excite me the same way the more sculptural works by more spatially-involved artists like Jim Hodges or Walter De Maria did. I think the acceptance really came from embarking into the history of painting on my own terms. It’s one thing to be directed towards appreciation through coursework. It’s another thing to allow your own curiosity to guide you somewhere deep and overlooked. The reality is, I had been looking at and making paintings my whole life, though the artists I was aware of were rural and wildlife artists who existed outside of the art canon taught in art school, and my own approach was just so illustrative and tedious that it felt more like drawing. I guess I still feel like I’m drawing with paint… I’m just loose with the language now.

Your website describes yourself as a ‘ruralcore artist’ – could you elaborate on that?

Absolutely. I would say I’m quite trans-disciplinary. My BFA is in Drawing and Sculpture, and now I’m predominantly a painter having earned my MFA in that area. I’ve also been known to employ various other mediums and methods such as slip-casting, wood-working and digital photography/video. Across these various approaches, my motivations remain consistent; I am using a layered combination of rural aesthetics, queer ephemera, and personal/contemporary imagery to demonstrate a reality of (and vision for) queerness in rural America. Essentially, I am using the visual language of rural America to illustrate queer storylines. Therefore, it makes more sense to describe myself via the visual motivation rather than any single physical medium… painter, sculptor, what have you.

Image by Ian Vecchiotti. Courtesy of the artist and The Valley, Taos.

What have you been listening to recently?

Now that it’s fully Spring, I’ll go hard on classical and instrumentals. Ezio Bosso’s Pines and Flowers is my go to for walks by swollen creeks. I’m mostly listening to music when I’m walking from A to B, so basically anything that allows me to briefly feel like I’m in a cinematic montage. Everybody’s Talkin’ by Harry Nilsson. Once in a Lifetime by the Talking Heads. Les Fleurs by Minnie Riperton.

In the studio I’ll throw on a podcast. Beyond the typical art programs that I listen to, I like hearing stories. I like hearing people tell their own stories. I’m subscribed to This American Life, The Moth, Radiolab, Normal Gossip, Always Sometimes…

Also, there’s also a really sick “Princess Diaries” playlist on Spotify by someone named Manda. I put that on when I’m driving and let it roll into radio mode. Highly recommend for anyone reading this who is in their late 20s.

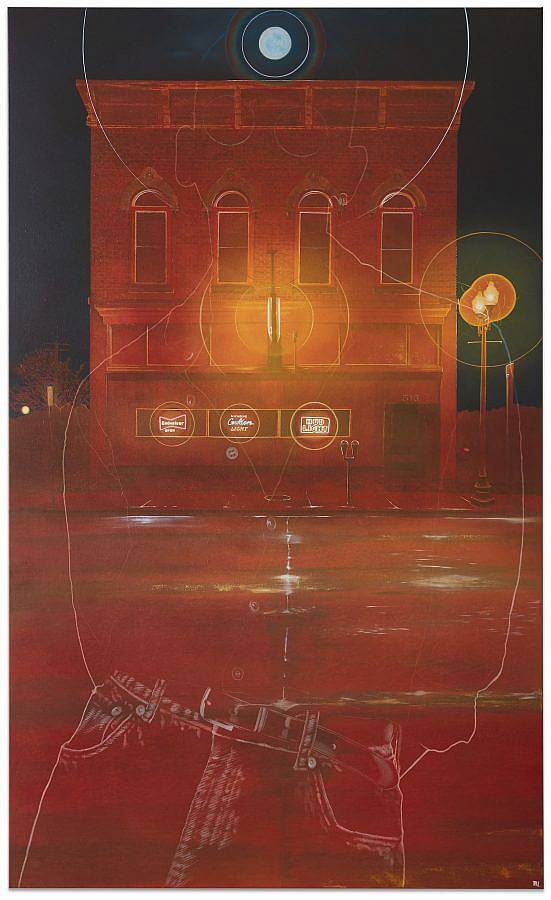

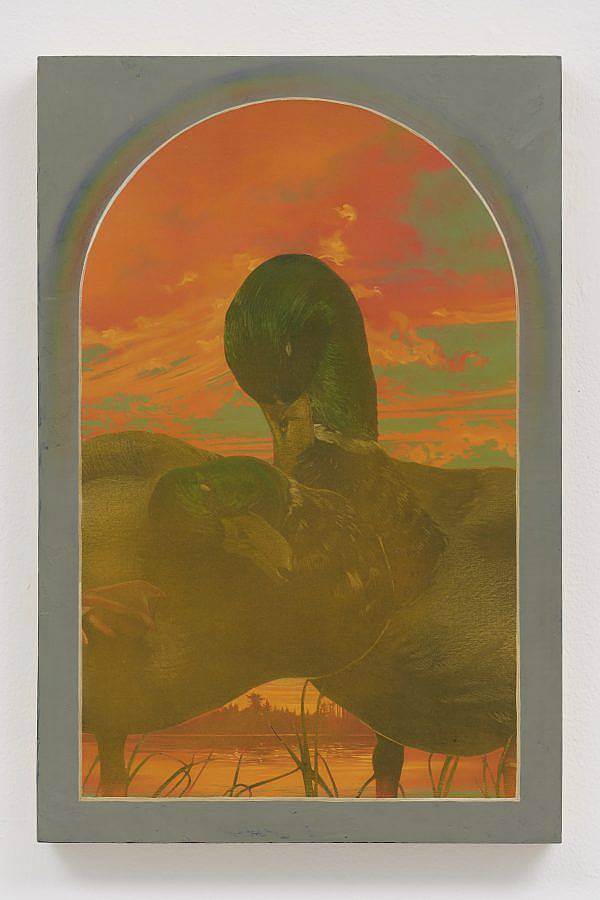

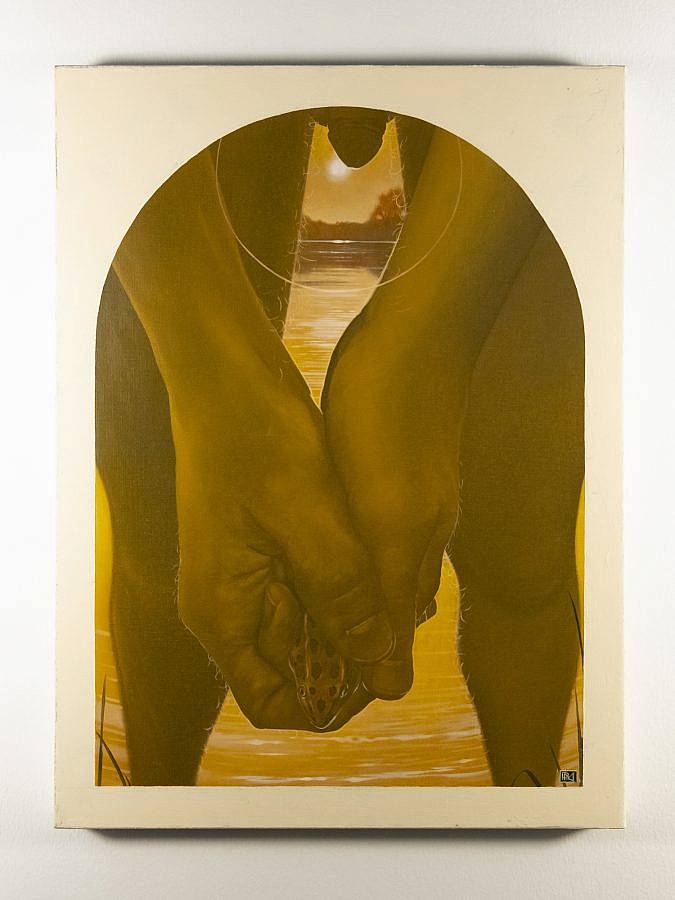

Image courtesy of the artist and 1969 Gallery

How was it like putting on your most recent solo show, ‘Purple Martin’, at The Valley in Taos?

Purple Martin was, for a number of reasons, an incredibly clarifying experience for me. Formulating and executing that collection of work allowed me to hone my understanding of utopias, and their potential as both memorial (past) and model (future). These were incredibly layered paintings and were a larger scale than I was accustomed to working at, so I felt constructively challenged in managing that work flow. I was able to bring all twelve paintings toward a completed state simultaneously from my previous studio at the Bridgeport Art Center in Chicago, even with a surprise solo exhibition of nine paintings tossed into the middle of that timeline. That really does feel like one of my most rewarding accomplishments to date.

To speak candidly though, painting for up to twelve hours a day for six to seven days a week presented other challenges. I have a tendency to bury myself in the work. Things outside of the studio will easily drop from focus, and when I’m finally able to step outside of the current I realize how isolated I’ve become. I’m still working on correcting those habits.

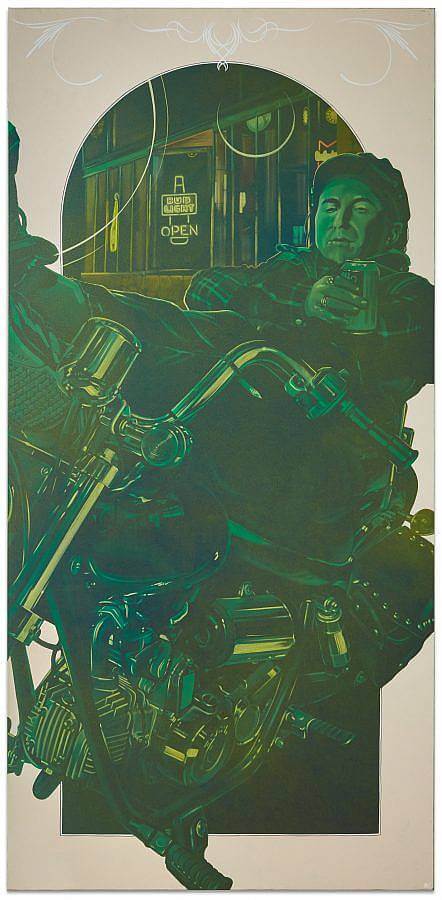

Image by Ian Vecchiotti. Courtesy of the artist and The Valley, Taos.

What does your studio look like?

I just moved into a new studio in Appleton, Wisconsin. The space is in an early 1900s factory building which has been converted into office spaces. The studio itself is pretty standard and it does the job well, but the neatest part is that my door leads directly out to a tree-lined lock built for boats to bypass the dams nearby. Appleton is a historic mill town with extensive hydro-infrastructure. We’re talkin’ Tainter gates and rail bridges up the wazoo. I haven’t seen any boats use the lock yet, but it is heavily frequented by Canada geese, cardinals, gulls, mallards, pelicans and swallows, which makes for great bird watching during lunch and snack breaks. Water and birds are two of my most favorite and centering interests. But yeah, the studio is good too.

A lot of your work tends towards a more muted palette – how do you think through color in your paintings?

When I’m painting, my focus is primarily on light and atmosphere, and I’ve been known to get a little deep in the glaze layers. How is the light describing the subject(?), and what does the air feel like(?) are my two constant considerations. So, when I’m thinking about the thick humidity of Wisconsin’s Northwoods region in late August, saturated in the golden light of the sun dropping behind a stand of white pines… I’ll begin preparing a translucent blend of yellow ochre, azo brown, and a knife-full of linseed oil, which will inevitably drench most (if not the entirety) of the composition. Who knows, if I’m feeling spicy I might toss in a little cadmium yellow medium. When all is said and done, the paintings usually end up looking significantly toned down or filtered – you say muted, I say unified – but it’s important to me that the atmosphere is as present as the subjects I am painting. It’s all about offering context. I suppose it’s kind of like adding salt to the tomato to make it taste more like a tomato.

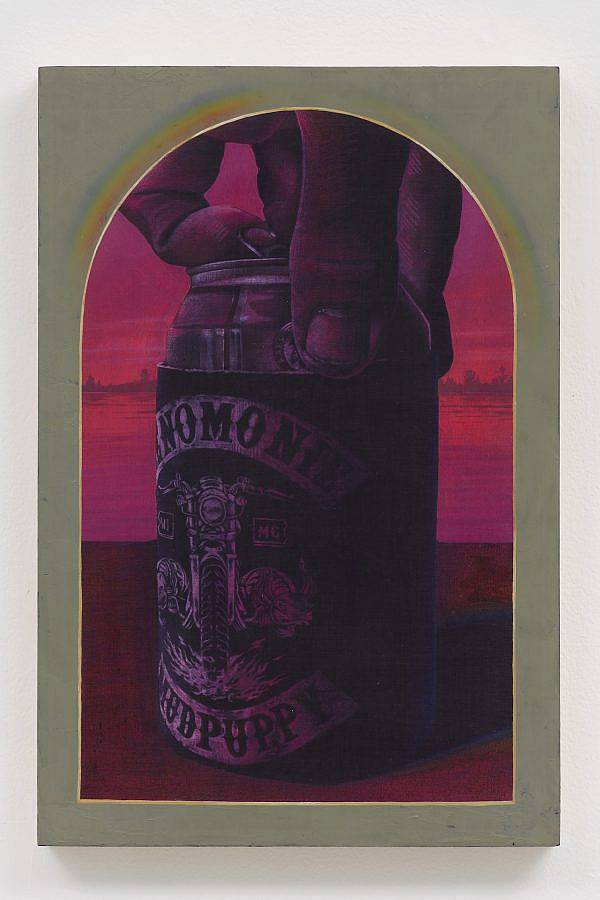

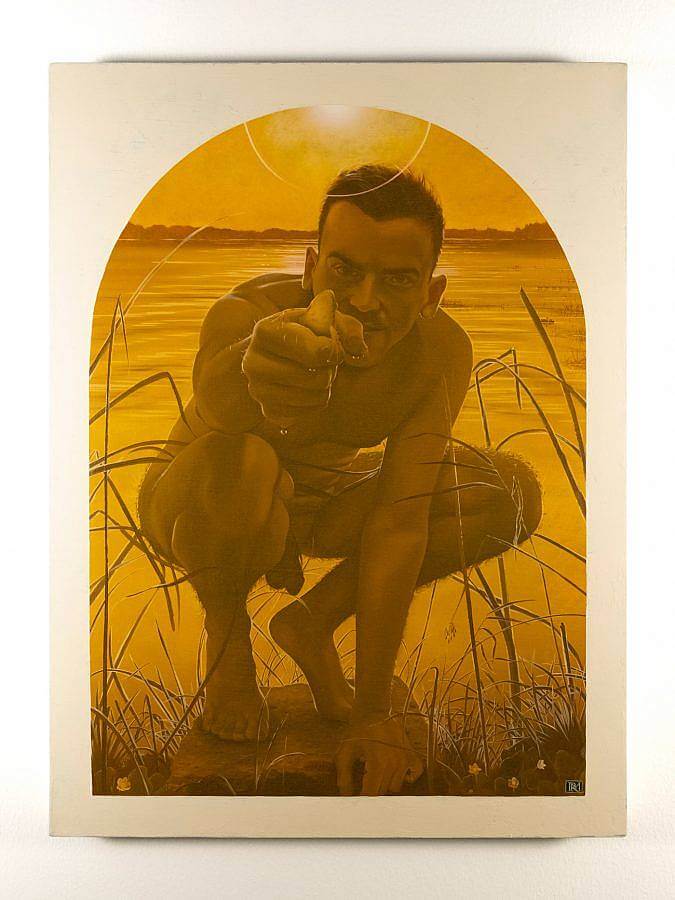

Image courtesy of the artist and 1969 Gallery

Should you feel vulnerable when painting? Do you?

I’m not qualified to direct or prescribe the manner in which an artist approaches their own work, but I will say my practice has felt more rewarding when I’ve been willing to observe a complete spectrum of emotions regarding my subject. Painting for me has been the deepest meditation. I’m never sure how the work will affect me, but I’m always open to letting it inform me. It’s a bit of a conversation in that sense. For instance, I’ve completed a number of self portraits at this point, and the work has always asked me to reckon with some aspect of my physical being. It’s not always easy to paint yourself honestly, but at the same time it’s not always easy to paint yourself lovingly. The act of painting becomes this sort of externalized mental processing of the subject, and thus it allows me to tangibly interrogate the way I am thinking about the subject of my translation. Beyond this, painting can demand a suspension of singular thought. When I’m spending hours, days, or weeks painting a portrait of my husband, the majority of that time is spent contemplating every bit of our relationship to one another; from the moment a reference image was taken and my emotions in that scene, to my feelings about him and us more generally. It can be exhausting, but it’s undeniably clarifying. Perhaps most rewarding is the way painting opens the door to memory. Anywho. I’m not saying you should feel vulnerable… but I’m not not.

How do you feel about framing, both in terms of actual frames, and framing inside of a composition?

Framing can be such a misunderstood–perhaps even misused–tool. I’m grateful that the sculpture program at my undergraduate school taught me to consider every single detail of a work and its presentation, down to the quality and positioning of lighting on a work. Regarding the arched compositions I typically employ; I think about the ways in which religion, for centuries, has used art and architecture to evoke fear and awe. An artist commissioned by the church might have painted a figure framed within an arch or cloister to demonstrate a closeness to God and heaven, or to encourage other spiritual considerations. Similarly, I use these tools to spark a consideration beyond the physicality of the subject, even when that subject might feel mundane or canonically out-of-place (or “unworthy”). I’ve also used physical frames to instill comfort or familiarity. One of my most favorite approaches in my early graduate work was to procure thick and ornate wooden frames with generous matting from thrift stores and replace the mass-produced landscape prints with my own queered versions of utopian rurality. Oftentimes the presentation of a work informs us of its intention.

Image courtesy of the artist

Do you have any guilty pleasures?

That one meme is popping into my head that’s all, “guilty about pleasure? What am I, Catholic?” And I want to channel that energy, but the fact (as you can probably tell) is that I was raised Catholic. So, unfortunately, I do feel guilty about pretty much everything I enjoy.

Lately it’s been my multiple-times-a-week Jimmy Johns habit. I love a hearty sandwich on sliced wheat, and I love when I don’t have to make it. I definitely feel guilty about buying otherwise simply-constructed sandwiches, though.

Any predictions for the rest of 2023?

My prediction is that earnest-and-queer bird art is going to absolutely pop off, and the next time you see me I’ll be on the Drew Barrymore show talking about my paintings of gay mallards. But I’ve always been shit at trend-forecasting. I really thought Bermuda shorts were here to stay.

Image courtesy of the artist

Do you have any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

For sure! Currently in the studio I’m working on a few smaller works for group shows later this summer, as well as a couple commissions. This September I will be participating in my first artist residency with Byrdcliffe in Woodstock, NY, and I will also be the Philip C. Curtis Artist in Residence at Albion College during the Spring 2024 semester. The Albion College opportunity includes a month-long exhibition in their Munro Gallery, which I’m just beginning to plan for.