Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I consider myself to be a storyteller. I developed a range of humorous characters and their backstories. My work’s comedic and sarcastic nature can be traced back to my childhood interest in watching cartoons and reading comic books. When I was a kid, one of the TV channels broadcasted cartoons at 5 pm for an hour every day. These cartoons were mostly from Eastern European countries and they had a very specific style. They were very rich in depicting the characters and they inspired me a lot. I also loved reading comic strips. I had lots of comic books and read them several times. I love the sarcastic comics because they are funny on the surface yet they convey a deeper meaning. As such, the reader can interpret them in their own way.

How did you get started as an artist?

I was raised in an artistic family and I was always interested in art. During high school, I would regularly skip classes to attend art courses. At the age of 12, my dad encouraged me to attend a specialized art school established before the Iranian revolution, which was very well-known for its teaching method. I majored in graphic design and illustration for my BFA and MFA; however, I wasn’t satisfied working as a graphic designer. As a graphic designer, you are always dealing with clients and don’t typically get a chance to talk about the issues you care about. So I decided to move to the United States to study painting and it all started from there.

Tell us more about Persian miniature painting and how this inspires your current work.

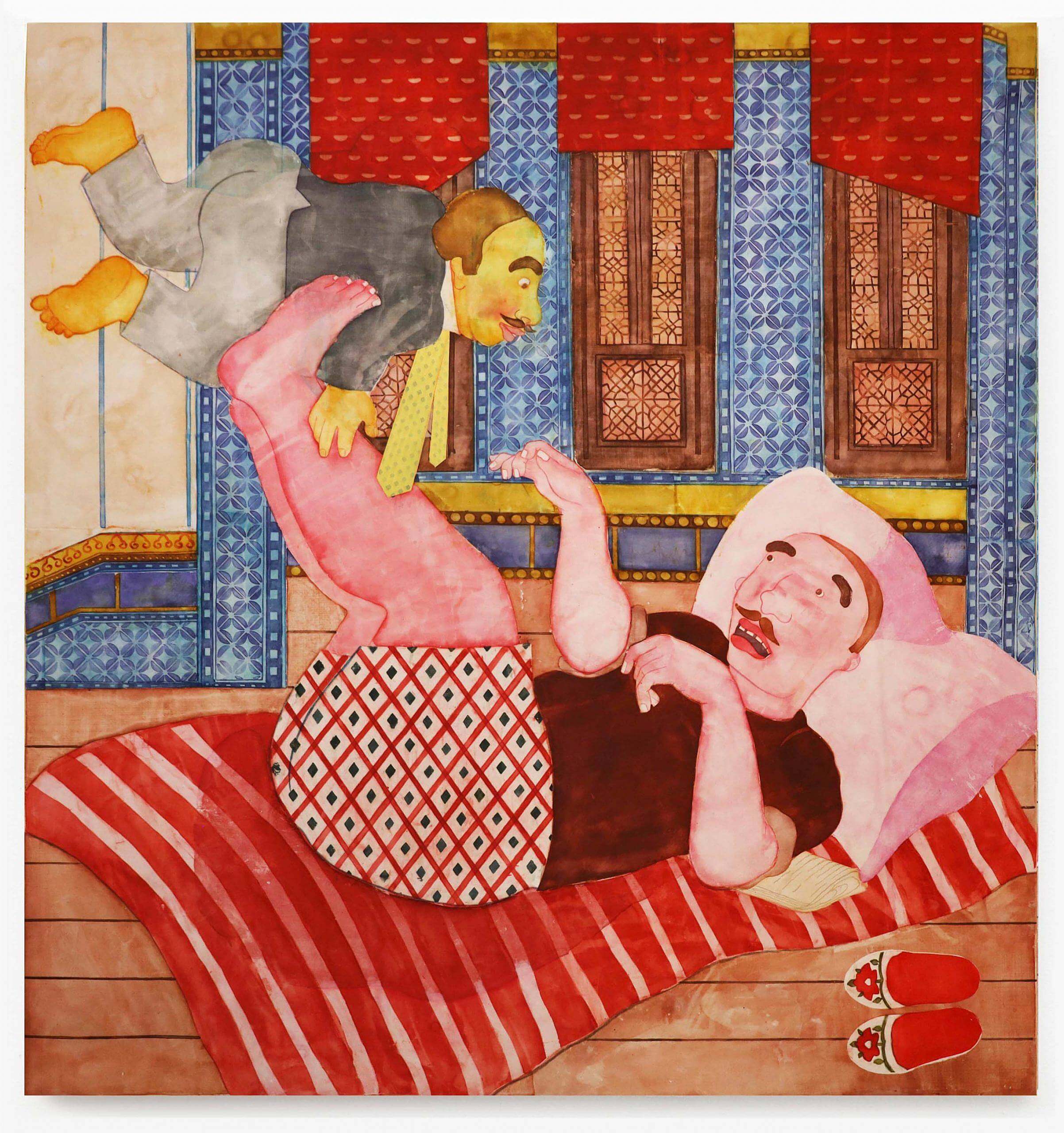

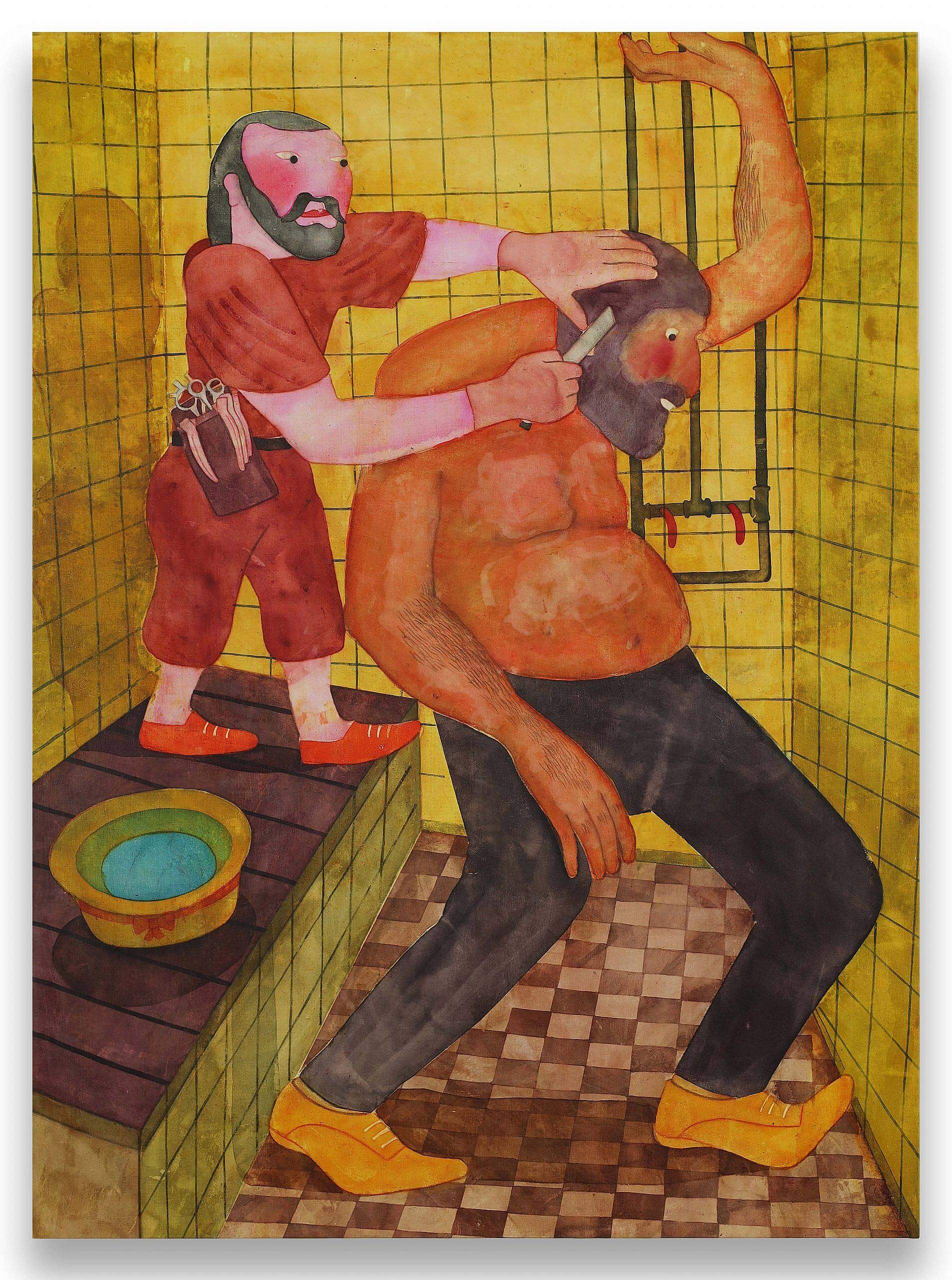

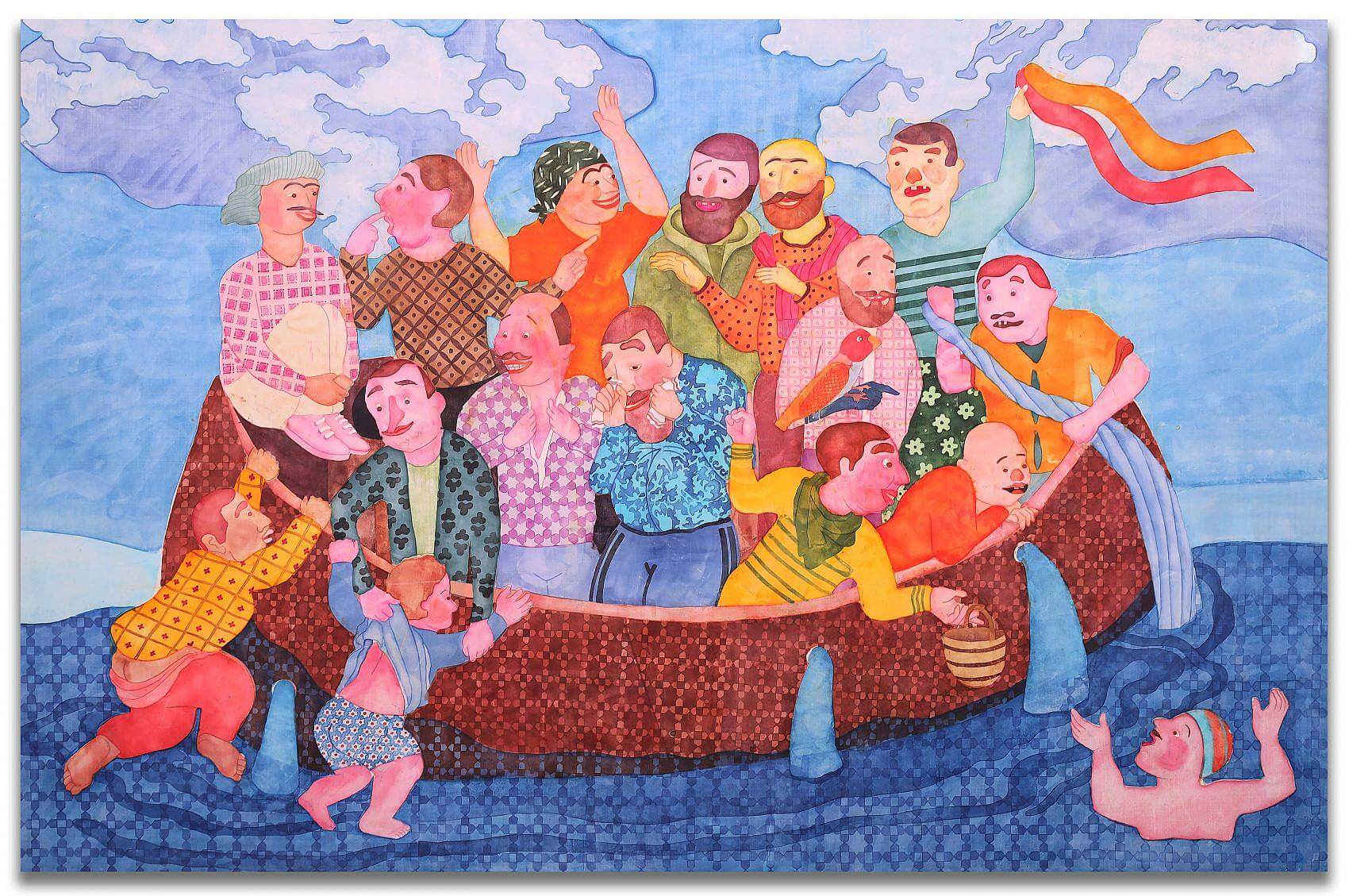

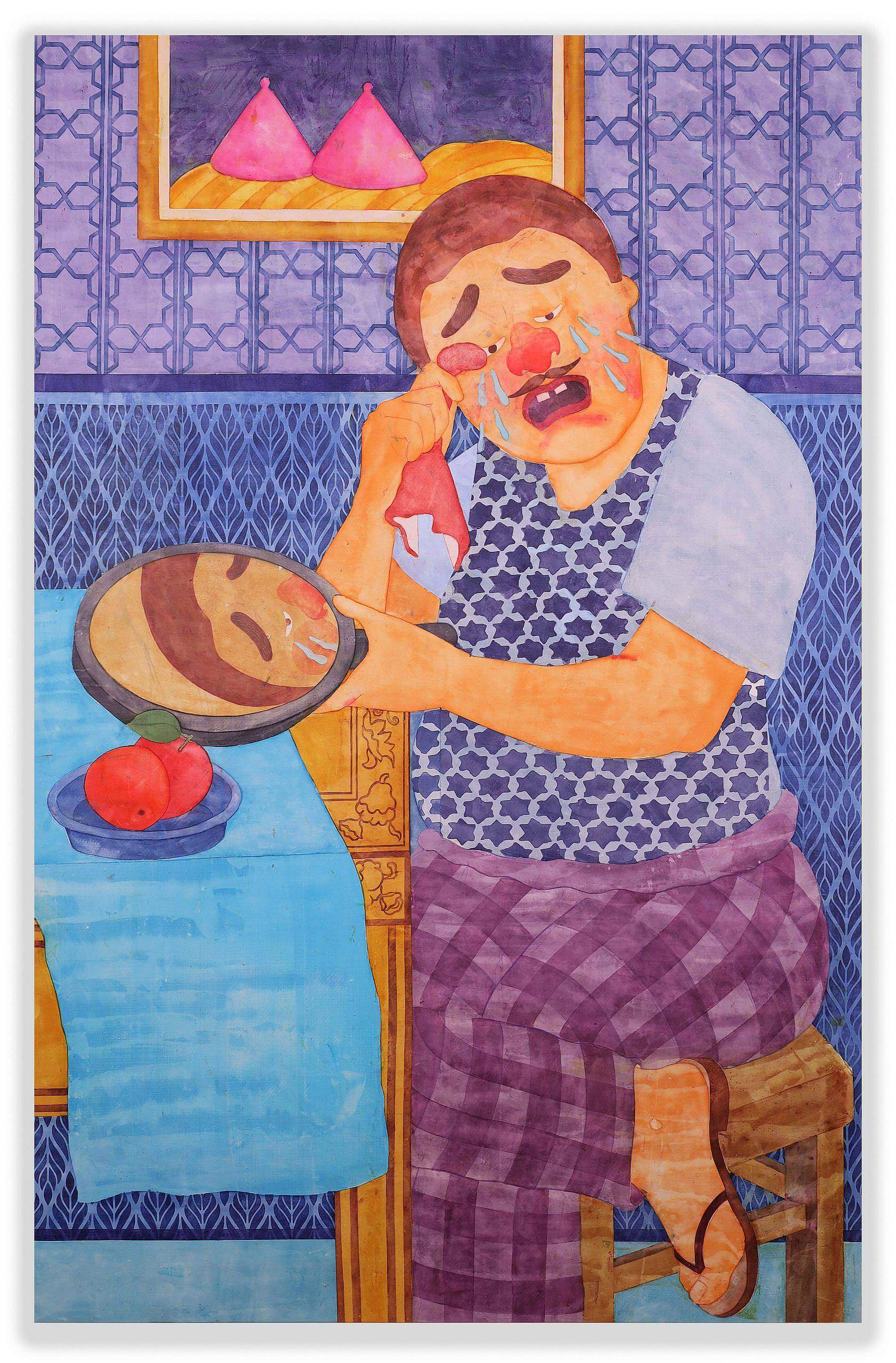

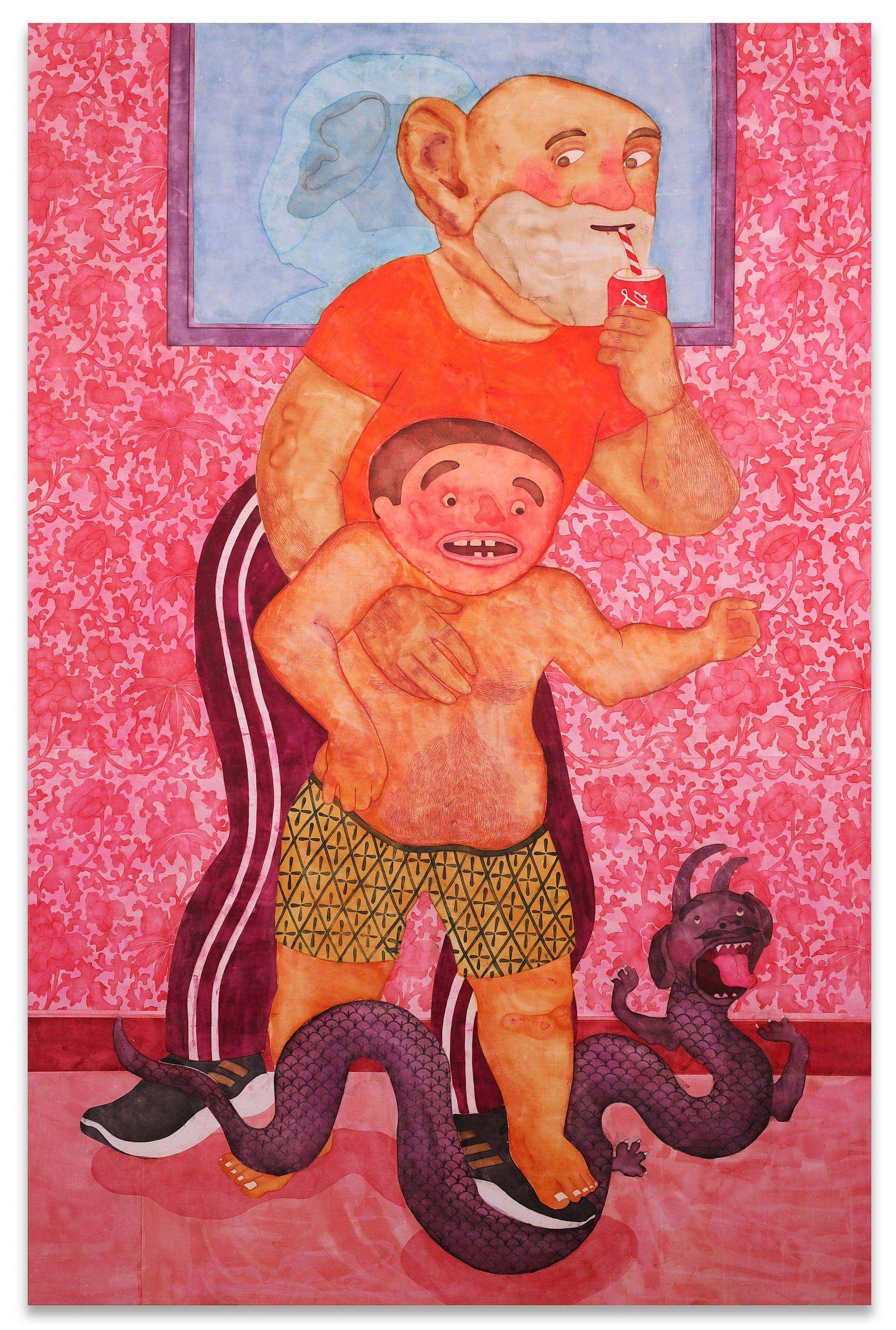

The most important function of miniatures is illustration. A Persian miniature is a small Persian painting on paper, usually illustrating a poem or story to make it more enjoyable and easier to understand. Everything in the Persian miniatures is flat, and the lighting is even, without shadows. Persian miniatures have their own specific definitions of perspective. There is no singular perspective in Persian art, like a Renaissance dimension. Buildings are often shown in complex views, mixing the interior views with exterior views of other parts of a facade. I grew up with Persian miniatures, but they didn’t significantly influence my work until I researched them. After a while, all of these aspects started to slowly appear in my art. In general, my work speaks very much to the history of Persian painting.

How would you define the medium of your practice? What effect are you striving to achieve through your particular technique?

I used to work with acrylic and oil paint, but I found that I was becoming obsessed with the details and would rework it until I ruined the painting. Later, I started experimenting with mono-printing and it helped me loosen up a little bit and have less control over the work. One of the fundamental qualities of mono-printing is the element of chance. I paint with dye on the screen and then use a squeegee to transfer the image onto the fabric. When I am transferring the image, it leaves so many stains on the fabric and I can’t do anything to fix it. It can be compared to writing with your left hand when you are right-handed; you don’t have the same degree of control. I accept the stains and work around them. It also helps me with the subject matter of my paintings since all the characters in my work have so many flaws.

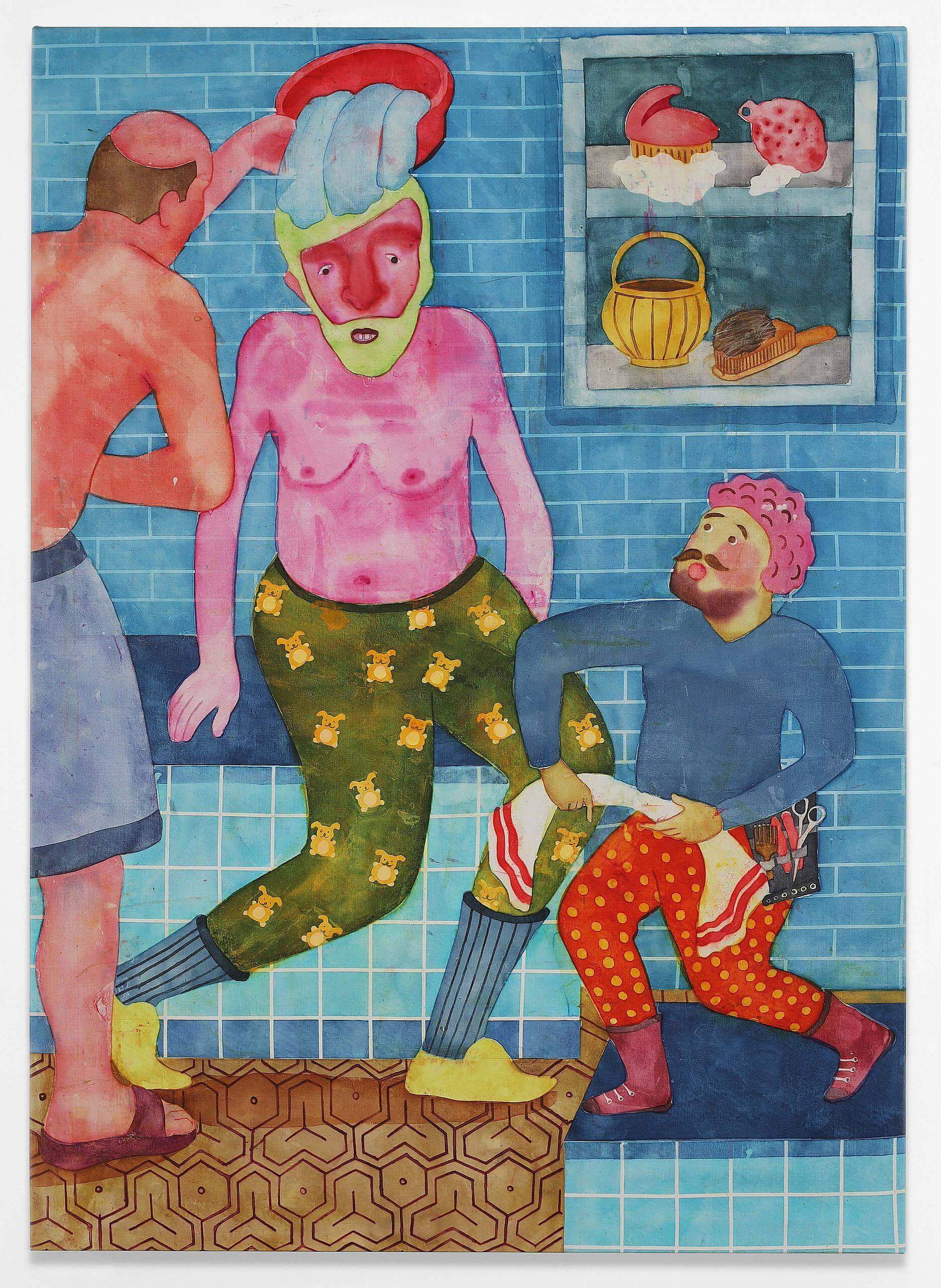

What drew you to the bathhouse as the setting of your recent mural, Peach House’s 5 Bucks Morning Special, currently on view at the MCA?

When I was commissioned to work on this mural, I was working on a new series focusing on the complex relationship between genders, which aimed at challenging the social structures in which people live. I started reflecting on gender-segregated environments, such as public baths. Historically, we’re not accustomed to seeing paintings of men from a female perspective. We have always seen paintings of hammam through the lenses of men, who were also the outsiders. My work seeks to redress this. I created a bathhouse full of the male characters I might have encountered during my life. Each character has their own story. I also ask the viewers to create their own stories by observing the painting. These characters are all busy doing different things: some of them are gossiping, some are getting a massage, one is cuddling a cat. The painting is inspired by the different scenes that adorn Persian miniatures. It is empowering to recreate images and question the narratives that men once predominantly contrived.

Intricate patterning can be found throughout your many scenes, and often even adorning the walls behind your paintings. Where do these patterns originate and what purpose do they serve in your compositions?

My use of patterns is inspired by Persian art. Growing up, I was heavily influenced by the beautiful tiles that adorned the old buildings and mosques that surrounded me. Persian miniatures and manuscripts were another source of inspiration for my paintings. Every element of the image in Persian miniatures is decorated with very intricate patterns. Juxtaposing these patterns with the images of these contemporary characters is a reminder of our relationship to the past. It’s like the past and present become interwoven.

The cartoonish humor and bright colors of your work evokes a playful reaction despite tackling heavy subject matter. What power do you believe play brings to the patriarchal themes you’re discussing?

The cartoonish style aims to challenge social structures of gender segregation. When one becomes fully aware of the surroundings, one can be critical about it. It really bothers me that the art world and the media both represent Eastern women as victims, voiceless and powerless. Furthermore, they typically expect us to represent this victimhood in our work. I didn’t want to be outspoken by directly referencing these issues, so I added humor to my work. The element of satire makes the work more universal and is accessible to different ranges of people. I think very serious things can be discussed through satire. I also think that when content is heavy, satire can help the viewer make more connections to the artwork. It’s a way to be discreet and humorous at the same time.

How has living in Chicago influenced your practice?

Since relocating to the United States, I have met people from different backgrounds who have experienced a range of personal struggles. It helped me to see everything from a different angle. Moving to Chicago also had its own challenges. I was trying to understand my artistic identity and the language I was using in my painting, reflecting on the relationship between the art history of the west and the art history in my home country. My works changed in different ways, but the content was always there. I was looking for a language to express what I wanted to say, and it developed slowly. I also got to know the work of Imagists. I like how they leverage satire to comment on civil rights, feminism, and wars.

What have you been reading lately?

I just finished the book ‘Hear the Wind Sing’ by Haruki Murakami.

Any upcoming projects?

My solo show with Nino Mier Gallery in Cologne ends soon and I am working toward my next solo show with Half Gallery in New York in June.

Interview composed by Ruby Jeune Tresch

Edited by Lee Schulder