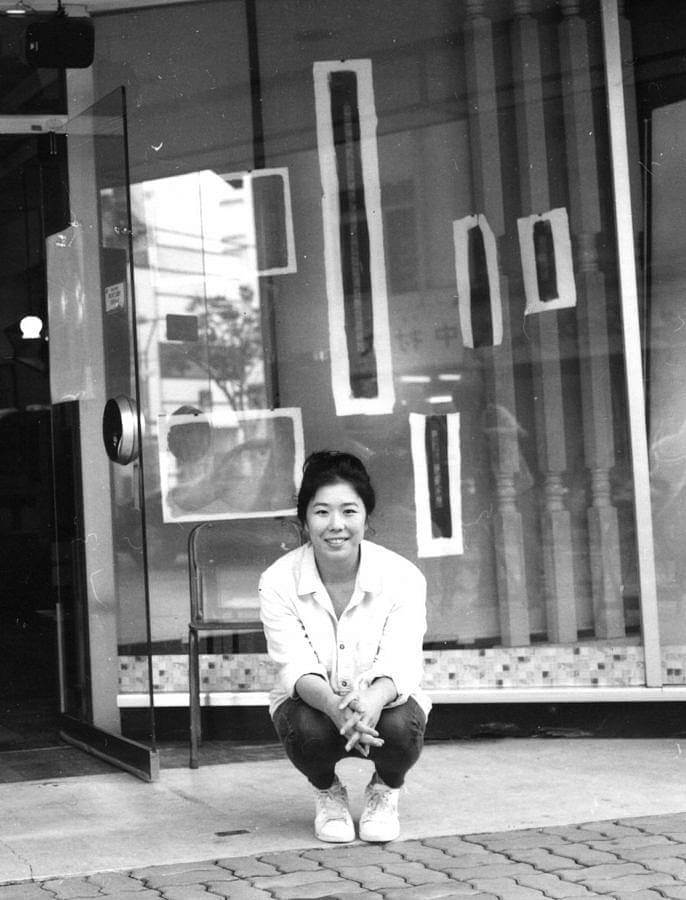

Tell us a bit about yourself, what you do, and how you started out as an artist and musician.

My musical practice is as a taiko artist, which is the traditional Japanese drum. I come from a performing arts family named Toyoakimoto with roots dating back to the Edo Period in Japan.

I curiously had a very conventional upbringing in terms of folk traditions: learning and playing with family, developing on stage, here in Chicago. My father grew up surrounded by the traditional arts as his family was running an okiya business, but he was also connected underground arts scene in 1970’s Tokyo. He then came to the US to pursue a career in jazz and film and experimental music. I started performing on professional stages in Chicago from about age 7 with my father and younger brother. It was just the three of us –and later including my younger sister– improvising all the time.

I have a visual practice as a photographer and filmmaker and went to art school for that. I’m interested in exploring the nuances of the mundane through various modes of perception, as a sort of politics of vision. I do installations and make artist books as well, but these iterations come all from a place as an image-maker. I have recently been working with site-specificity, incorporating the material and spatial histories of exhibition spaces.

I think I realized I wanted to pursue art more seriously or professionally during my graduate studies. I was beginning to be able to contextualize how my two experiences and mediums inform one another or naturally converge under the identity of an artist. I am carrying on my family lineage in Chicago as a taiko artist, exploring both traditional and contemporary applications of this kind of music; while also maintaining a different but parallel practice as photographer, filmmaker, and educator.

Looking at the building blocks of space and photography–light, form, and time–how do you feel the return to those elements relates to your practice?

I think my practice is a return to these elements. My work acknowledges and accentuates these fundamental elements of time, space, form, light and movement within the mundane, using the idiosyncrasies of conceptual photography and experimental cinema. And through the notion of material specificity of the analogue image and image-making process. I am very much drawn to the sort of (maybe romanticized) universality of them too. This is the same reason I am drawn to hands and the human body as well.

When one thinks of the continuous and tactile nature of analog processes, it makes sense to draw ties to memory and sentiment. How do you mean to explore analog information sharing in your work?

What most attracts me to the analogue is in the philosophies of thinking, and making, of waiting, of taking time that are already a part of the process of making that I feel are sometimes lost in digital media. Film is nostalgic, black and white images are romanticized, I’m a nostalgic and a romanticist, but I have always been conscious about making sure my work does not get lost within nostalgia. The ties to memory and sentiment have to do with keeping, which is connected to intimacy. I suppose the everyday has to do with intimacy too. I want to keep and share these quiet but very present moments that surround us everywhere, all the time. It would seem silly to ignore these connections to sentimentality but I do feel that part of the challenge is to make sure memory and sentiment don’t appear as concomitant frivolities.

Tell us about your solo album No Traffic in Space, which was released this year.

No Traffic in Space is my first solo album released in March of this year through Asian Improv Records. I’ve recorded for other artists’ projects and with my taiko group but this is my first solo endeavor. The album pulls from my earliest memories and experiences with music and is a collection of some of the textural and conceptual gestures that I have been thinking about and exploring recently.

All improvised of course, and whole takes.

I have two special guests on the album: Michael Zerang and my father who graciously agreed to be a part of this project. I know I wanted to do Wedlock for my first solo work, which is actually the opening piece on my father’s album Kioto; he made an album for each of us three children. I listened to the album a lot as a child and I remember just loving that particular sound and groove. The original piece is my father on bass and Michael Zerang on drums and for this iteration, I am now the one playing that wedlock phrasing on taiko. We recorded an additional two pieces since we were all together and those are also on the album.

All of the images are mine. My designer Al Brandtner knows I’m a visual artist and interpreted my photographic work for the album design. I’m interested in choreographic articulation as part of musical expression and felt it was important to share visually the different configurations of my drums, so I photographed myself in all of the setups: sitting down, standing up, between two drums, one large one, etc. for the cover.

How do you think about silence and absence in physical and auditory landscapes?

Silence is so important within my practice and as part of my artistic philosophy. Silence is everything. It is the space of silence that truly carries energy. It is so much more fluid and ambiguous than the absolute. This mentality is very Japanese, because Japanese culture is one that so carefully pays attention to the hidden and unseen. We recognize the elegance in quietude, secrecy and invisibility because we understand the potency of silence. This is different from absence which I feel as a concept negates potency. Silence is a negation but there is a potency in the absence that is silence.

I don’t think there is much absence in my work – I mostly use silence.

Your compositions capture the utopia of everyday life, a reverence for the seemingly mundane and vernacular forms that make up our routines as bodies in the landscape. How do you feel you approach capturing the everyday?

I relate the mundane to silence. It often goes unnoticed but everything is there. My reverence of the mundane is a sort of politics of vision, or sight. To appreciate and see what already exists around us. I’m not creating new landscapes really, but I am accentuating the nuances of the everyday landscape. That’s where all the nuances start to become noticeable. Light is light but is not that light, it’s this light. It’s my hand, the artist’s hand but also your hand and all of our hands. I love playing with nuances, both visual and auditory.

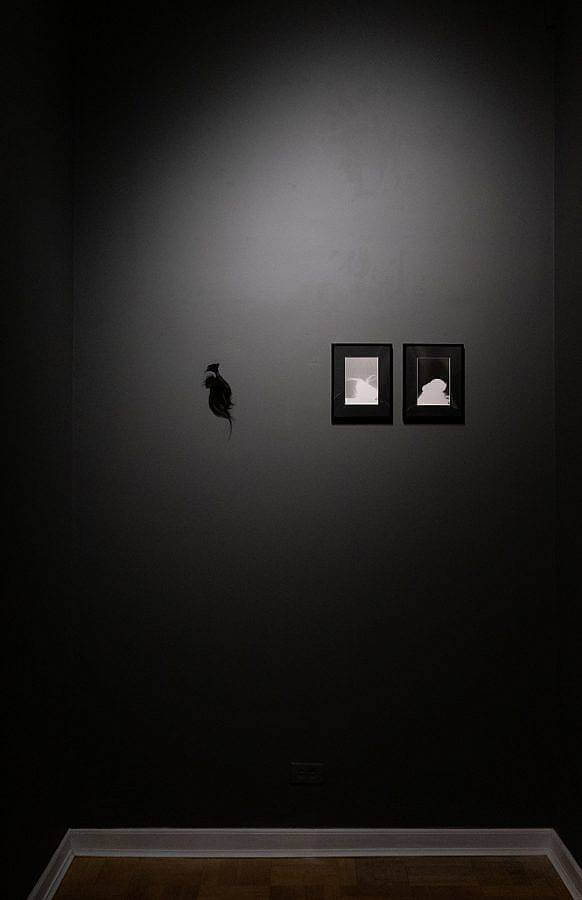

Can you tell us about the Signature Bun series you have up on the fourth floor of the IMSS?

This series is its core is a documentation of my time in the darkroom. Every time I do a printing session, I first make a test print to ensure the chemicals are working properly. About a year ago I started making these loose photograms by holding the paper behind my bun and exposing with a flashlight as my tests. I wasn’t particularly thinking about creating a cohesive body of work then. It was more trying to break up the monotony of this very practical exercise. There is one grey print in this grouping since I felt it went well with the grey walls of this specific room, but the grey really functioned as a signal that my developer was weak and needed to be changed that day.

The title of the series comes from the simple fact that a messy, high bun has been my go-to style for at least the last 15 years, for its ease. In this room, there are about 50 images total which is the number of prints I had at the time of install.

I’ve also included a lock of my hair from when I got my hair cut, also about a year ago. Hair is an accumulation of time, and each print is a unit of time. The physical hair serves as a visual point of reference too since the images themselves are quite abstract. And everything is hung at my actual bun height. I’ve continued making these images so I think this series will be a perpetually growing collection.

When installing or performing your work, how do you consider the room you’re in? How do you fill the space?

Recently I have been doing a lot of site-specific installations and bodies of works that respond to the spatial, material histories of the rooms or buildings of the spaces I am exhibiting in. Other times it’s considering the architectural layout of the space and creating work from there. I’m not so sure I am thinking of filling the space so much as really responding or paying homage to it.

Are you reading anything right now?

Hervé Guibert’s Ghost Image.

Interview composed by Maddy Olson