Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

In the 90s, after prolonged atheistic suppression, the spiritual boom hit the post-Soviet region, revealing a bizarre psychological and semantic glitch that left a remarkable trace on me. Specific memories, such as the first seen funeral procession moving slowly through the city, an open catafalque decorated with two spruces installed from both sides of the deceased, stuck to my young brain. It was a highly intriguing time; television broadcast psychics’ sessions hypnotizing water while most union assembly halls were occupied by various religious sects, expanding like mycelium. I think the family tradition of picking mushrooms contributed to my practice essentially; it was not just the form of a reunion within nature but a way to survive the intense economic crisis that hit the system at that moment. My long-standing fascination with forests and rivers appeared as the need to escape a stagnating dimension of the socio-sphere. Later, the first personal computer and the internet made everything even more delirious, granting access to a wide range of cognitive distortions that often caused a hypnotic effect.

Today, my method applies the lenses of scientific research and spiritual search to the information society and its atavisms.

How do you think about making sculptural work versus making installation work, if you consider them separate?

As far as I remember, I intended to create dimensions or spaces filled with the atmosphere that would trigger all possible receptors. In a way, it’s like the since-fiction concept of an oracular engine on board a spaceship that simulates native places to relax astronauts. I think of installation as one interconnected organism where sculptures are its agents. I like the ancient idea of building relationships with an object, which is opposed to contemporaneity’s disposable logic. In general so-called inanimate nature or Geosphere, it’s something to rethink.

How did your current show at Management in New York come about, and did you do anything different in the work for it?

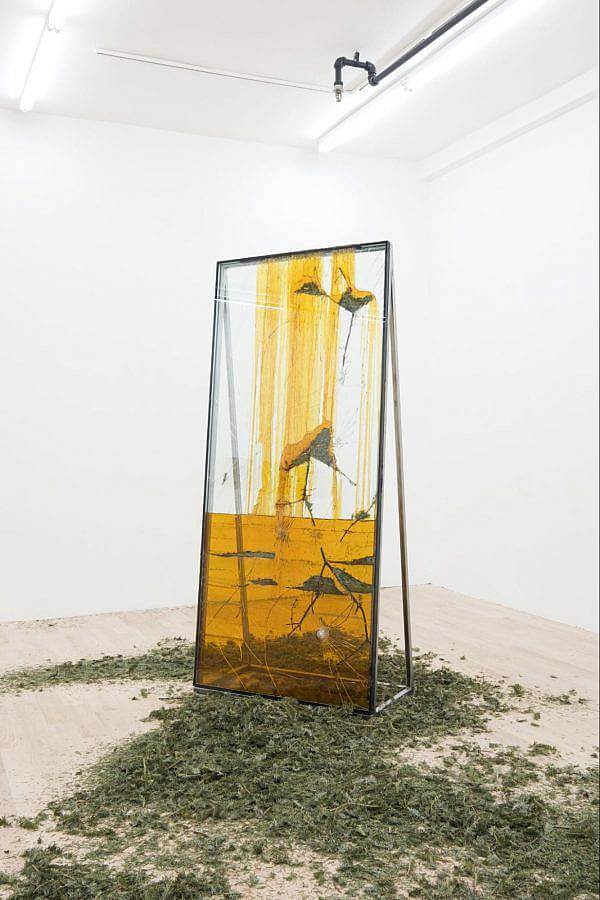

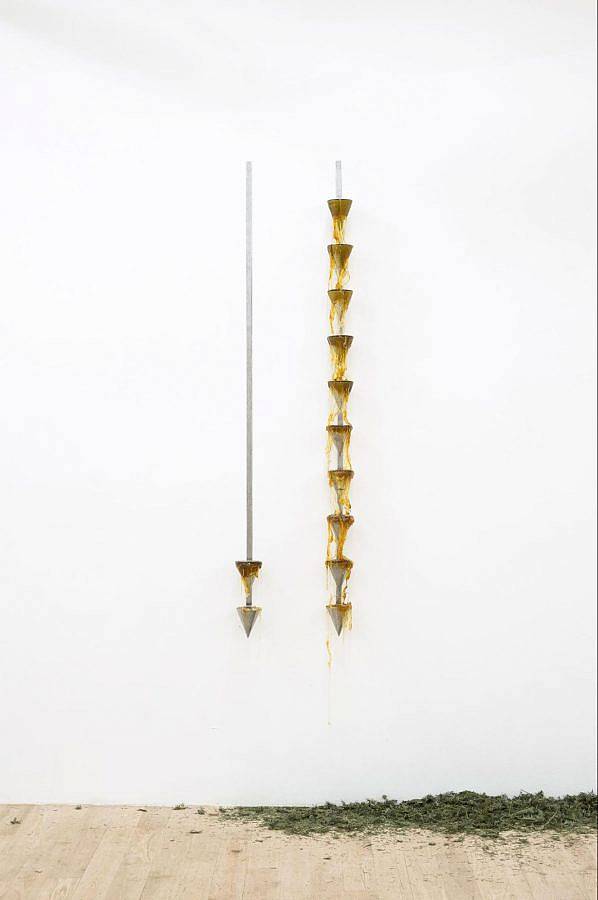

In January 2013, I had my first solo show called ‘Requiem for a New Year’ in Minsk, Belarus. The central video of that exhibition depicts collecting New Year’s spruces from the trash in my town. Ten years later, I repeated this ritual in New York; that’s how this needles carpet in the gallery space appeared. More specifically, the exhibition touches on genealogy and interspecies connections in light of ethnoreligious beliefs. One of the show’s key elements that influenced the overall concept is a pre-candle (and most likely pre-mirrored) era lamp. The lamp is arranged to hold pine rushlights, while the water basin is intended to reflect and multiply light, preventing the dwelling from catching on fire. According to ethnographers, a pine rushlight has reproductive symbolism; in many Slavic beliefs, pine fire was associated with passion, lust, and procreation. It’s interesting to admit that local tribes used coniferous forests and trees for burials. This is how, most likely, the coniferous trees acquired the mediating function to connect to ancestors.

A lot of your work has various organic materials sandwiched in between double-glazed glass window units – how did that mode of making come about?

It all started with the conflict of binary logic. Perhaps, the double-faced Janus, the patron of the calendar and the god of transition contributed to that. The idea of a ‘parallel world widespread across various belief systems always appealed to me. Such notions as ‘Through the looking glass’ overlapping with the liminality concept made me focus on the idea of a portal and passage. Once, I locked two wine glasses filled with green dishwashing liquid into each other; this is how it began. Later, rethinking the idea of cyclic and linear time, I replaced this poisonous chemical substance with pine resin.

Whose work are you really excited about right now?

There are many artists whose works I’m excited about, especially now that artists are breaking the distinction between past and future, erasing the border between living and non-living nature, and rethinking our coexistence within an ecosystem.

What function does video play in your practice?

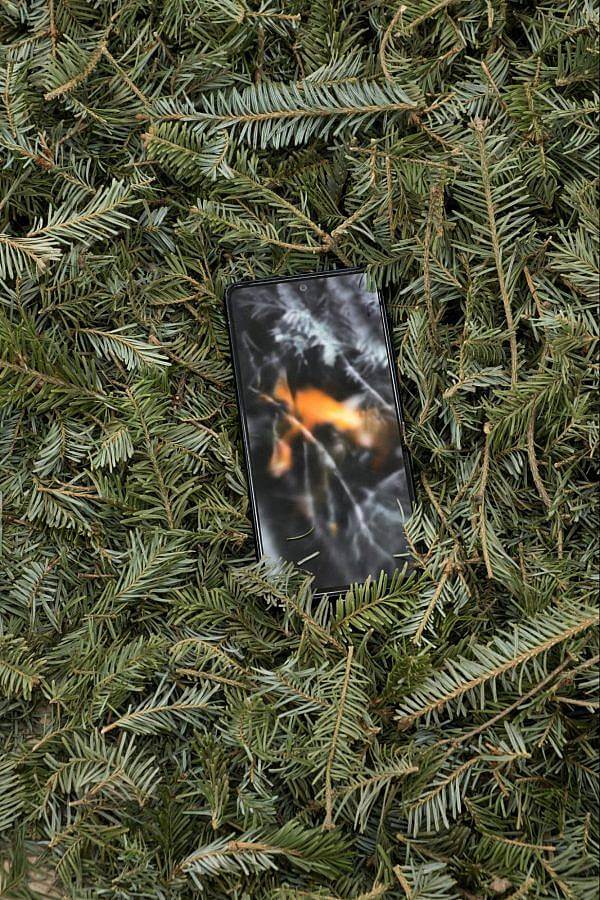

I used to think of fluid mediums such as video, sound, or smell as the spirit of an installation, animating it. Since my artistic practice started with music, I have had time to comprehend its fluid and repetitive nature, which serves the essence of trance or hypnosis and forms the basis of nearly every ritual. In fact, I’m not enthusiastic about the idea of info channel separation. I adore synesthesia, which acquires a new meaning in the conditions of the info sphere merging with physicality through simulative experiences. Included in my last show AI-generated video eponymously called “Coniferous Succession” depicts a fiery squirrel accompanied by an ethnographical audio compilation played from a smartphone. In northern mythology, a divine squirrel operates as a messenger on the tree of life, connecting the upper and underworld, while in Slavic mythology, a ‘Leshy’ takes the form of a squirrel that speaks with a human voice, confusing people and leading them astray. In its turn, the smartphone was connected to the wireless speaker installed in the gallery’s ventilation system, tying the exhibition into one mental ecosystem.

How is it like living and working in Berlin?

Berlin is very calm in the sense of pretentiousness. I like that, although it can intensively discredit artistic potential while charging you with humanistic generosity. Somehow, I haven’t found an ideal place yet; being in between different economic zones is probably my share.

What’s the story behind the use of Pine Needles and Resin in your work?

In various beliefs, coniferous trees had apotropaic functions. Northern and Eastern European tribes worshipped trees like many other tribes worldwide; this is why the concept of a ‘World tree’ or ‘Tree of life’ is so ubiquitous. Some indigenous people believed there were trees with blood floating in their veins. At the same time, certain coniferous trees were thought to be twins of particular people, so in the case of death, the spirit would migrate to the tree and inhabit it until all the needles fell from its branches.

I remember resin development sites in my native forests; it would always trigger empathy in me, especially knowing that trees generate resin as a healing mechanism to fix injuries. The work called ‘Hardens on the surface and heals the wound’ captures those feelings as well as the other pieces included in the show, which together form an organism fossilized by dozens of liters of this primary form of amber.

How do you usually approach making work for a solo show?

All my projects are interconnected. I like to think of them as a turbulent flow frozen in silt. In a way, it’s a decentralized infrastructure with some parameters that I adjust manually. The rest is a methodology relying on a UX design strategy with stages like research, ideation, conceptualization, mapping, etc. The project’s initial phase is often embodied in a virtual tapestry woven from various visual references, notes, 3D renders, videos, and links. Talking about “Coniferous Succession,” the process originated in long-term research studying the mythological cosmology of my region. My works often merge the mythological with the technological, and this one isn’t an exception. For example, the series of wooden panels, “Walking, knocking on the roots, and shaking the spruce paws,” resulted from a collaboration with AI. Ethnographic prompts were fed to the system to generate phyto-morphic reliefs related to the mineralization processes. Afterward, they were carved in pine wood, emphasized by soil, and covered by resin.

What have you been reading lately?

As I mentioned, lately, I have been chiefly into ethnographical texts describing ethnoreligious pre-Christian beliefs of Northern and Eastern Europe. It’s always a pleasure to see how the scientific lens refracts the beam of mythology. Besides that, I just finished the first book co-written with artificial intelligence, Pharmako-AI, by K Allado-McDowell.

Do you have any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

I am preparing to show my work “Neophyte II” within the consonant group show in Slovakian Bratislava. Some more projects are coming, but I can’t share them yet.

A hybrid CGI video is something I’ve been thinking about lately. It will prolong my Neophyte cycle, where animated nature expands in young people’s neurons. Within this cycle that started in 2019, the forest is seen as a place of protection, a shelter for magical and partisan forces, and a space of non-linearity. I like prioritizing phyto-morphic intentions over anthropomorphic ones. Along with this, CGI’s impact on Interspecies relations has occupied my thoughts lately.

Interview Conducted by Milo Christie