Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

I was born and raised in Havana, Cuba, right after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Growing up under a totalitarian Communist dictatorship made me a very skeptical person. For me, doubt is an ontological necessity, and it is intrinsically related to my instinct for free will and self-determination. That’s one dimension of my personality. Another one, ironically a product of the Communist ideology, is that of a romantic, a true believer: not in a political system, moral creed, or religious dogma, but—along with Plato—that beauty is the splendor of truth. For me, those opposites—skepticism and idealism—find synthesis in the experience of the work of art, which is artifice (construction, illusion, deception) and reality (actuality, emotion, transformation) simultaneously. My current work is about that ambivalence—the fine line between artistic sincerity and manipulation.

How do you describe your practice?

I’m a recovered conceptual artist, in the sense that I reject the idea of art making as a tool to communicate a specific meaning or content. After a few years of trying this and that, my current practice focuses on painting in a self-referential way. I’m interested in the painted surface, the process of creating an image, and the mechanics of illusion.

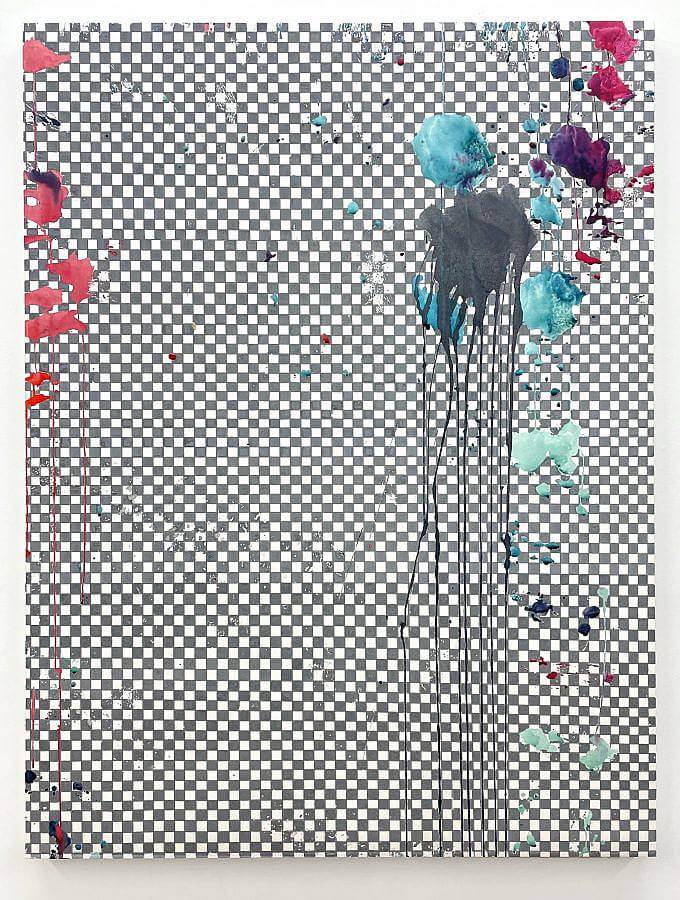

My paintings are colorful. I use a combination of acrylic markers and watercolors. I like watercolors for their intense luminosity: the transparency of the medium allows the white of the paper to act as a Lightbox, which provides the surface with a very vibrant brightness and I like how pure the pigments remain during the process of production. One can perceive the organic quality of the minerals used in some colors; the smell, viscosity, and chemistry are present in a way that reminds me of the first cave paintings. In contrast to these qualities, acrylic markers produce an impersonal, uniform surface; they are opaque, constant, and contained. As a technology, markers are fairly recent. Their invention dates to around 100 years ago. They are used mostly in what are commonly regarded as art-adjacent disciplines, such as graffiti, illustration, and design. The support of the work is usually built from paper stretched on wood panels.

I create these paintings in two distinctive steps. The first one is fast, gestural, and driven by chance. It is at this stage that the loose and washy watercolor marks are created. I approach the paper without a preconceived sketch or idea of the outcome, letting the physicality of the brush dictate its own path. The only restriction in place is to avoid figuration. If the marks are too loaded, I would incline the surface and let it drip, mixing different strokes and colors in the process. After the painting dries, the second phase takes place. It consists of filling out any fragments of the paper untouched by the watercolor using acrylic markers. I’m in full control of this second step. It is mechanical, detailed, slow, and predetermined by what is already there. The background then becomes aware of itself (it is no longer secondary but central). The marker’s opaque and saturated quality contrasts with the fluidity and transparency of the water-based painting.

What are the main motifs in the art you make?

Loose brushstrokes, splashes, drips, grids, and patterns. The last two relate to rationality and culture—logos if you want. The gestural marks refer to spontaneity and chance, spirituality, and pathos. In general, I’m curious about the history of abstraction and how it relates to social constructions, gender, and power. I’m also curious about what makes a good painting. In terms of objective quality, where is the leap between a lobby and museum art piece?

In addition to the use of paper and canvas, I use cowhide as a surface to reference modernistic explorations of metaphysics and the transcendental. In some cases, the cowhides are combined with different forms of electronic light and sound devices, such as neon lights, keyboards, and speakers. In my installation This Was the First Time, a keyboard on the floor is activated by the weight of a metal figure. The specific key played corresponds to the sharp C note that opens Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring). The 1913 ballet depicts various primitive rituals celebrating the advent of spring, after which a young girl is chosen as a sacrificial victim and dances herself to death. This idea of the propitiatory and ceremonial is one of the underlying interests behind the use of animal skin for this body of works, as well as the idea of the artwork as a trophy—a display of social power and dominance.

It is important to acknowledge that painting on animal hides is a longstanding tradition of the Great Basin and Great Plains indigenous people in the United States, including the Kiowa, Lakota, Shoshone, Blackfeet, Crow, Dakota, and Osage.

What excites you about being an artist?

It might be a cliché, but I have a hard time describing myself as an artist. I prefer the word painter. What I love about it is that painting and drawing are some of the most accessible means of visual expression. The direct and immediate action of making a mark on a surface has been a primordial instinct of both early humans 45,000 years ago and myself alike. I started painting around the same age that most children do. The reason I continue to do it today is because playing with the alchemic mechanics of pigments still makes me happy. Besides its immediate sensual character, for me, to paint is to mimic creation in the theological sense—to create something out of nothing. It is also an attempt to provide the viewer with the joy I receive from painting as a form of sensual, sensorial, and spiritual experience. These and other definitions of the nature of painting as a discipline and an action, although useful, are limited. They might throw light into the history and sensorial implications of the medium, but as an art form, the experience of painting is not something you can use words to describe. I believe that’s why Leonardo Da Vinci—who was a scientist as much as he was an artist—said he wanted to be known as a painter rather than a scholar. I’m also excited about how there seems to be an inversely proportional relationship between a good painting and its logical discernibility. Lee Ufan mentions in his notes about Henry Matisse: “Since a painting is nothing but a painting, it should be a painting before it is anything else,” and Julian Schnabel stated, paraphrasing the late Ad Reinhardt, “The paintings are the paintings, and everything else is everything else.” I really subscribe to those statements.

Favorite quotes/mantras?

I really resonate with this Gerard Richter quote:

Theory has nothing to do with a work of art. Pictures which are interpretable, and which contain a meaning, are bad pictures. A picture presents itself as the Unmanageable, the Illogical, the Meaningless. It demonstrates the endless multiplicity of aspects; it takes away our certainty, because it deprives a thing of its meaning and its name. It shows us the thing in all the manifold significance and infinite variety that preclude the emergence of any single meaning and view.

His work and artistic philosophy have been central to the way I understand artmaking. One of the reasons I moved to St. Louis for my MFA was to have constant access to the monumental pieces on permanent display at SLAM.

Who are some of your favorite artists?

I feel that my current work is an opportunity to channel the artists that I admire the most. In this regard, no one has had a stronger influence on my work than Christopher Wool. I discovered him in Cuba when I was a teenager. Back then, I only had access to his “text paintings”. They were irreverent and sexy, original and simple, conceptually strong while visually striking. On my first trip to New York in 2013, I visited his retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, and there I encountered the work that became deeply relevant to me: large-scale monochromatic abstractions made with a combination of digitally manipulated photos of previous works that were silkscreened and then re-painted or wiped in gestural blurs. The images were beautiful and aesthetically pleasing, but unlike Rothko’s color field paintings—which I also grew up admiring—these pieces were complicating their own perceptual experience in a way that connected more with the ambiguity and playfulness that are so fundamental for me as a creator. Wool’s paintings are sincere simulations of expressiveness. They are aware of their own condition of artifice in a way that, for example, a painting by Jackson Pollock or de Kooning is not. It is this specific approach to the medium that informs my work. In contrast to Wool, I don’t rely on the combination of different disciplines (photography, printmaking) to deconstruct a conventional approach to abstraction. My process stays instead within the realm of painting and uses different tools and treatments in an attempt to subvert preconceived notions of abstraction as a genre.

Another artist who has had a profound impact on my recent paintings is Chris Martin. His large-scale canvases are unapologetically beautiful. Along with oil and acrylic, he uses non-traditional art materials like glitter, newspaper, carpet scraps, and vinyl LPs to create colorful, abstract compositions that are reminiscent of modernism in their rigor and consistency but also feel current given the use of non-conventional materials and the acid—almost fluorescent—color palette. I hope that my recent work, while being in direct conversation with Abstract Expressionism as a movement, feels contemporary and part of this day and age. In that sense, when making some of my technical decisions, I think of Chris Martin and his vibrant surfaces.

Central to my practice also is Rudolf Stingel. His work debates in a more direct way ideas about artistic perception, the process of creation, and overall notions about painting. Using intricate mechanical processes as well as industrial materials, he creates paintings that are intentionally illusory and contain trickery. For example, in the late 1980s, Stingel began a series of works on paper using the technique of applying oil and enamel paint to paper through a tulle screen to create monochrome paintings with texture and fine patterning. Later on, at the Venice Biennale in 1989, he published an illustrated “do-it-yourself” manual in English, Italian, German, French, Spanish, and Japanese, outlining the equipment and procedure that would enable anyone to create one of his paintings. By doing this, he subverted the trope of the European Renaissance’s painter-genius or post-war American painter-hero as well as notions of originality and style linked to Western modern art. When I make my own work, I’m attracted to the idea of a painting that anyone else could potentially do.

Other artists whose work has had a significant impact on my recent work are Helen Frankenthaler, Robert Motherwell, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Gene Davis, Gerard Richter, Jason Rhodes, Mike Kelley, Julian Schnabel, Sean Landers, Sterling Ruby, Ugo Rondinone, Charline von Heil, Katharina Grosse, Katherine Bernhardt, Albert Oehlen, Matt Conors, Bernard Piffaretti, Mary Heilman, Pablo Tomek, Secundino Hernandez, Dan Devening, José Lerma, and Mike Cloud.

What do you want a viewer to walk away with after seeing your work?

William Shearburn—a very dear friend and colleague—told me after seeing some of my paintings at a group show, that they made him happy. That’s one of the biggest compliments I’ve ever had, and all that I hope for my work to do.

Describe your current studio or workspace.

I moved to New York City earlier this year. I was lucky enough to find an amazing studio space in Long Island City a couple weeks later. It is located two blocks away from MoMA PS1 and one train stop away from Manhattan. I come here almost every day after I finish my duties at my day job (I’m the Head Preparator at an art gallery in Chinatown). In addition to my practice, which is a very individual and solitary experience, I really enjoy doing things that connect me with other artists and creators.

What’s your hottest take?

That painting is not a form of communication. It is not a symbolic device. For me, a good painting is more similar to a Zen poem or a symphony. It should connect us with that which ordinary language cannot: the ineffable, the absurd, the “vital force”, in the words of Ernest Becker.

What have you been reading and listening to lately?

I’m currently re-reading Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground. I think its message of how brutal and selfish human nature is unfortunately more relevant today than ever. Regarding music, I’ve been listening to Keith Jarrett’s discography nonstop since I was a teenager. It is my default choice when I need to recalibrate and reconnect with myself. If there is such a thing, I think he is the most important musician of the 20th century, although I can see how that’s another hot take!

All images courtesy of the artist. Interview conducted and edited by Natalie Toth