Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I am a British-born artist, originally brought up in Norfolk and now living in Rome. My work mainly involves sculpting and casting in metal but I work with other mediums too.

What are some of your essentials while working in the studio?

My cat Dagmar’s company and Music.

What first led you to jewelry-making?

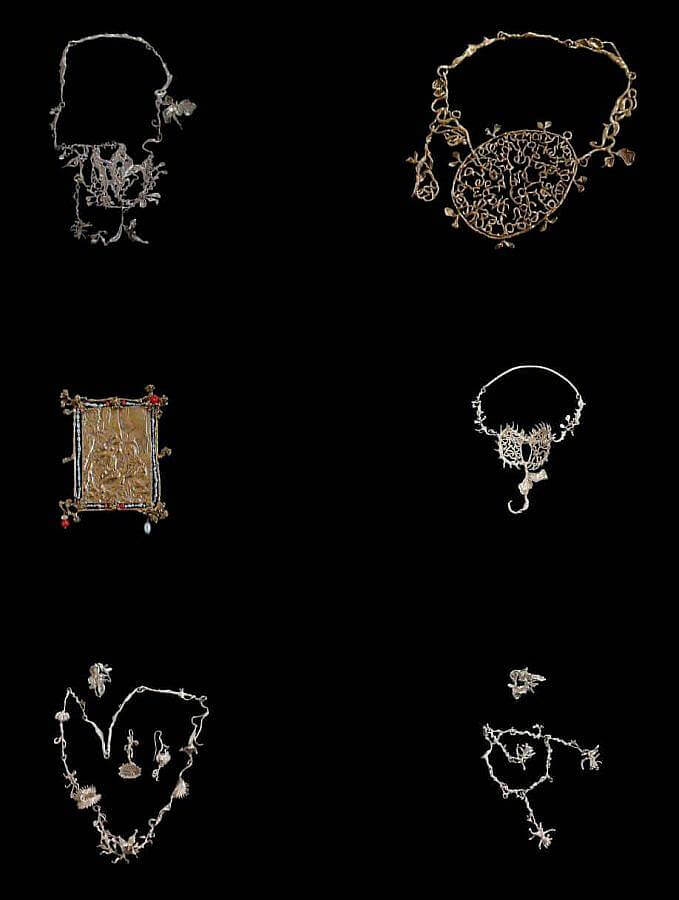

I think jewelry making is an extension of some of the sculptures I work on that can be worn on the body. I had been collecting old jewelry for quite a while and that led me to try and translate some of my ideas into jewelry-like pieces. I started with a few simple tools and then gradually built a small home studio of sorts.

How does being able to wear a piece of art affect the experience of the viewer?

I think this is more of a question for whoever carries one of my pieces out into the world.

How does the overlap of personal and collective mythology influence your imagery?

There is not one particular influence that draws my work to its final place. I’m especially interested in the mythology of the sea and the different ramifications of the subject across different cultures. I find it very inspiring when I connect with water, and it impacts the methodologies I employ to achieve the final look for some of my sculptures

How does your approach differ when making wearable versus non-wearable pieces?

I think they both start in a similar way whether I’m working with metal or fabric. I always start with the materials in front of me and let them guide me to what they might become. I then start making some fragments without a final scope, to begin with. I always try to keep myself free of too many ideas at the start of the process and then it starts gradually growing and building up into something that feels right. I like to make many ’scrap’ like puzzle pieces. Most get abandoned, remelted, or used later down the line.

Sometimes when I’m lucky these forms magically align with some thoughts or research I’ve been doing at the same time. They show me a clear line I can follow all the way to the end into something solid.

Tell us more about the experience of teaching yourself lost wax casting and what interests you about this particular method.

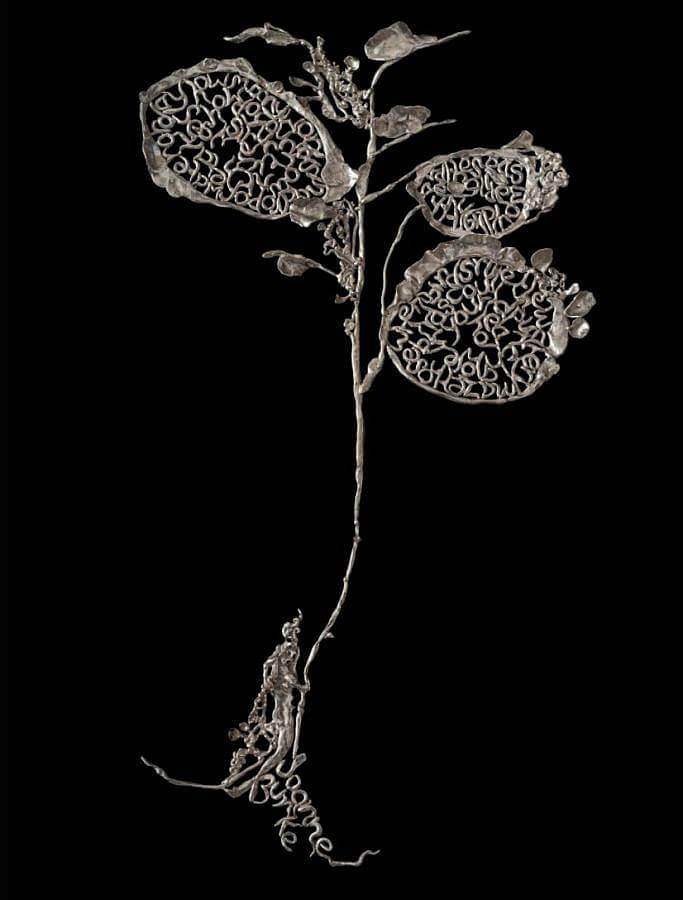

I get really excited to open casts and see how my wax has been transmuted through the process into metal. Seeing that transformation can be quite addictive. It’s a really magical process. Sculpting with wax is my most favourite part of the whole technique and I spend a lot of time developing new ways to work the material to experiment with new textures, lines, weights, and spaces. That is what interests me most.

Describe your “poetry pieces”. How are these works different from other wearables you’ve made?

I have been writing for a few years but never really doing anything with any of it out of fear of anybody actually being able to read what I have written.

In some way I want the words to be out there somehow just for myself. So I found that incorporating text was a good way of releasing the words, where they were still disguised and confused enough that you’d have to be extremely committed to decipher what was actually written there. Then whoever has the desire to do so really deserves to know what is written. So there are complete ‘poems’ if that’s even what they are, but they whirl around and the words connect to each other in a stream so that they almost look more like a pattern if you’re not paying close enough attention.

Favorite poems?

“Old Shellover,” by Walter de la Mare, “Goblin Market,” by Christina Rosetti, “The Bettle,” by Nikolay Oleynikov, “Any anagrams,” by Unica Zurn, “Mirror,” by Sylvia Plath, and “Caterpillar,” by Chrstina Rosetti.

As a self-taught artist, how would you describe your relationship with the often hard-lined traditions of craft?

I keep myself very free of any of the usual constraints when it comes to hard-lined traditions although I’m very inspired and deeply respectful of craftspeople who have worked hard at what they do. I really do not know any professional jewel-making techniques so I feel quite lawless when it comes to my craft.

Not knowing anything when I began meant that I had to generate my own sort of system to make my work. I feel a sense of freedom from that lack of knowledge. I make my own tools and use other tools for things they weren’t initially intended for. I think that adds a certain energy or spirit that you can’t necessarily see with your eyes but can definitely feel in some way whether you know it or not. At least that’s how I feel.

Tell us more about your forays into garment-making.

I have been making my own clothes since I was a kid so it’s just something that I have always enjoyed doing. It’s very experimental. I wouldn’t consider nor is there an attempt to establish myself as a clothing designer. I would just define them as an extension of the rest of the work I do, which by default is another extension of myself.

While still retaining motifs of imagery you’ve depicted in previous wearables, many of your recent works have become much more abstracted. What prompted this shift?

Feels just like a natural evolution. I think in the beginning I wanted to make myself a few pieces to wear, but then as things progressed and I got into the potential of what could be achieved with wax casting, I got carried away with experimenting. I taught myself new ways as I went along. It’s just natural that things have become more abstracted as time goes by since so have I.

What draws you to the oceanic forms and symbols depicted in many of your pieces?

I grew up in a rural seaside town in Norfolk, England and so the sea has just always been very present in my life. My connection with bodies of water has been very emotional since a young age. I couldn’t swim until more recently because I almost drowned as a kid. Back then I would spend every day in summer on the beach collecting sea glass, shells, wearing seaweed hats, uncovering old clay fisherman pipes, digging holes, and burying friends in sand. I think when you’re younger you are more receptive to the nature that surrounds you and growing up in a small seaside town really ignited my attraction for mysterious things. I never stopped collecting sea treasures, looking for gateways, or appreciating anything that might look a bit undefined or otherworldly. Being brought up around all of this somehow helped me find myself reflected within these forms and experiences that now relate to and impact my work.

Interview composed by Ruby Jeune Tresch & edited by Joan Roach.

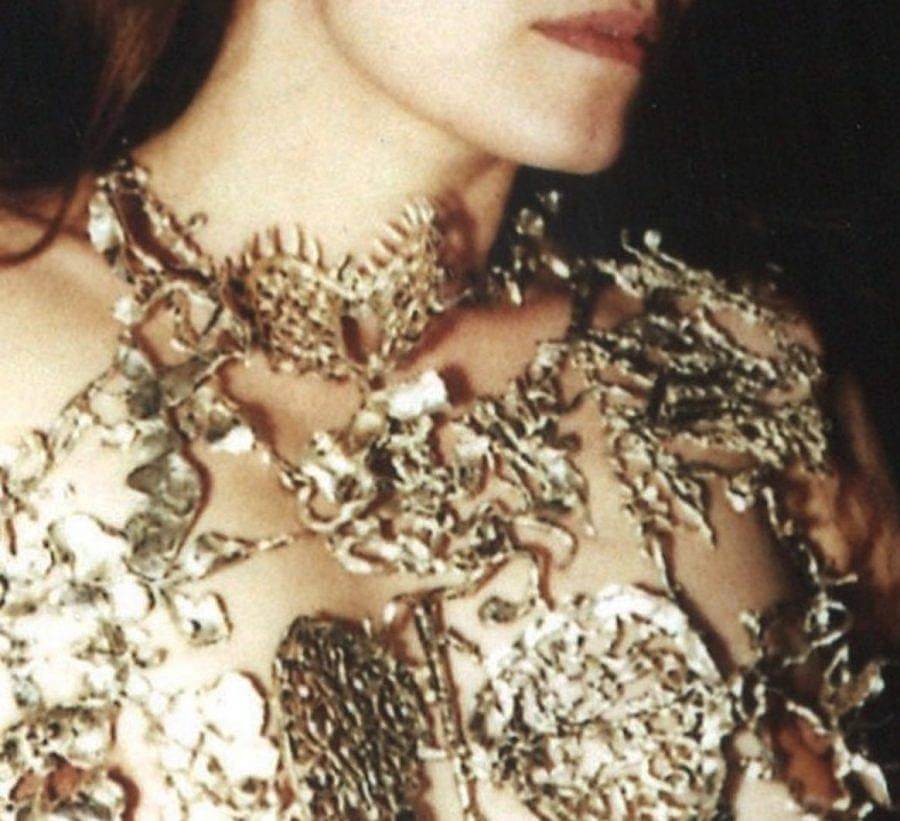

The featured portrait of the artist, wearing one of her poetry pieces was photographed by Emi Maggi.