Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

I’m currently a full time artist and, I suppose, as I recently came across a lovely Paul Haworth quote about reveling in the “avalanche of tasks–big, insignificant, complicated jobs–as the unavoidable truth of doing something in the world,” a juggler. I wear a lot of different hats in various projects that all broadly serve as research trajectories. These days the logic behind everything I do follows the general metric of “Will this make me a little less depressed? Y/N” haha.

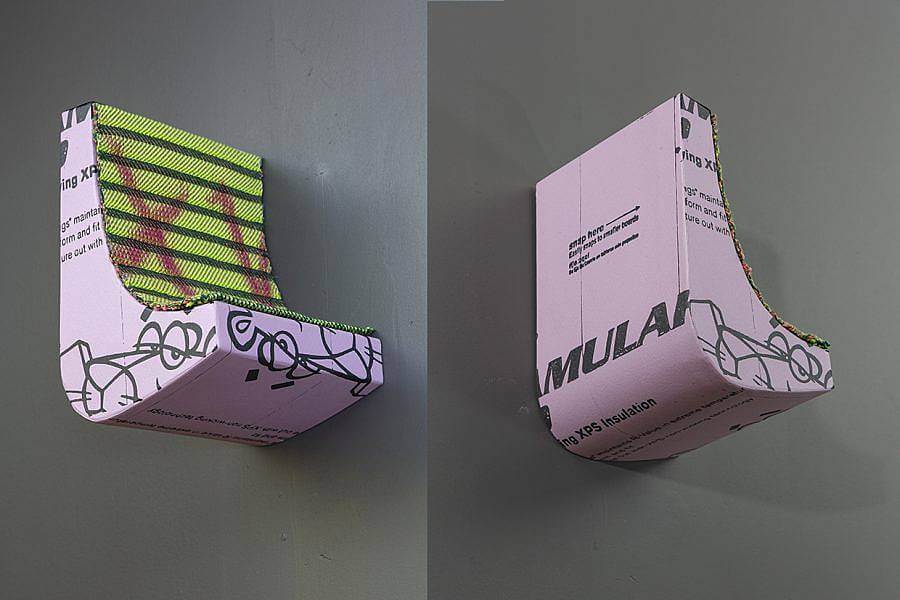

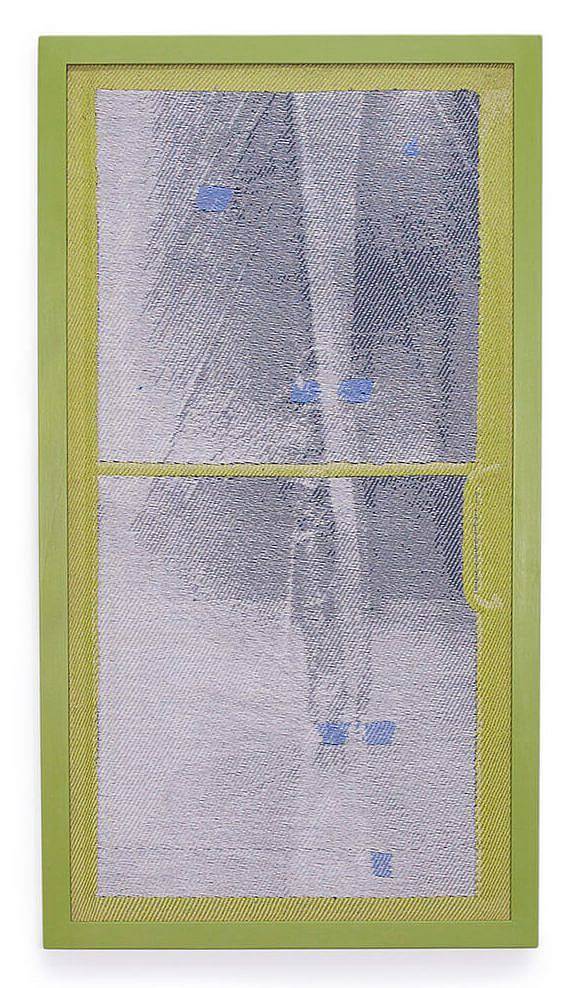

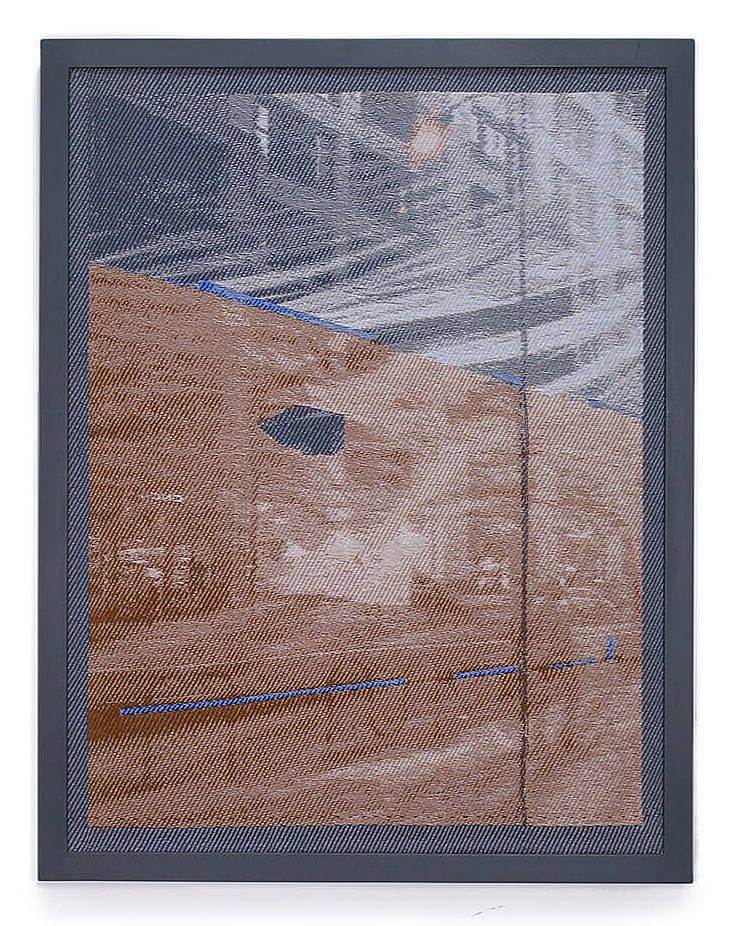

In my studio, I’ve been oscillating between grieving over loss in multiple forms and designing elaborate inside jokes with myself, both through meticulous trompe l’oeil screenprints, paintings, and weavings. I’m interested in the projected desires born out of that kind of material mimicry, codes of spatial authority, and the personification of our structural environment as a method to examine conditions of alienation. I’m also interested in visual language and assumed perceptions of reality – how linguistics shape, individually and collectively, the ways cultures conceive of order and “truth.”

Can you talk about your interest in construction and utility materials?

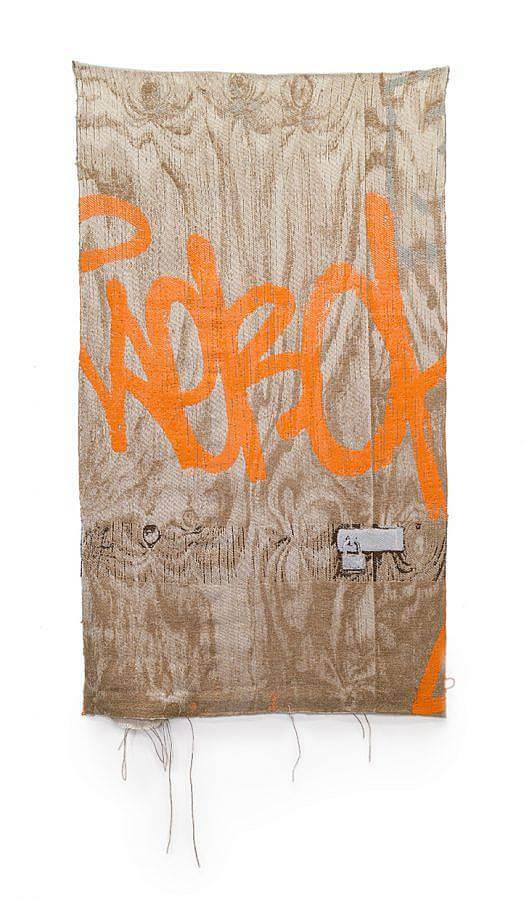

In the past few years, I’ve worked in physically and emotionally taxing manual labour roles, such as a printed textile manufacturing and exterior architectural historic preservation. I namely use repetitive processes like screen-printing and hand-weaving to package my observations of human activity around industrial sites of labour and architectural remnants. While much of these are merely surface level observations about textile and construction industries, I’m constantly thinking about pay inequity and arbitrary value of labour under capitalism.

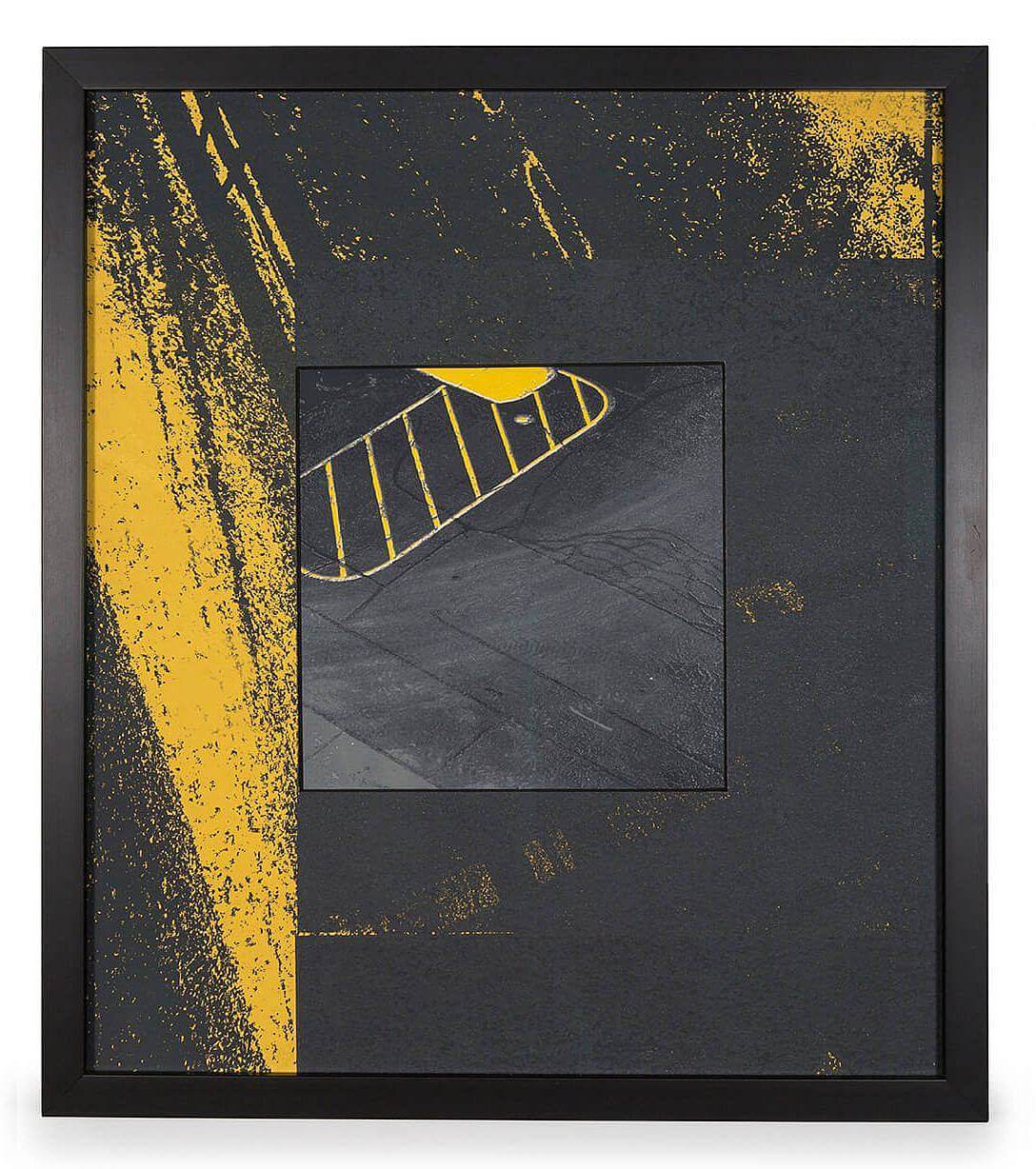

Essentially a lot of my imagery and thoughts come from job sites and commuting around the city. Which really just means I make art about sidewalks and walls.

Your statement mentions your focus on “architectural scars, ” can you elaborate on this phrase? What’s one of your favorite instances of this “scarring” and why?

I could talk my head off and go down so many rabbit holes about this! The first time I remember regarding architectural facades in this way was on a 2015 study trip to Siena, Italy where a geology professor first introduced to me the political histories of rocks – who wanted it dug up, who are the actual labourers of excavation, and what kind of violence is enacted in transporting/collecting/erecting material. Italian architecture stands on a long lineage of cultural standards that can be traced to the Renaissance conception of mathematical perfection. Along the facade of Siena’s town hall, the Palazzo Pubblico, you can find a “scar” along one of the windows where bricks had been nominally shifted to accommodate the exact geometric lines of the piazza, a shape informed by the number of members in their city government. Small scars in these buildings suggest intellectual shifts in values. Though the scar might be seen as imperfect or a mistake, they indicate a staunch pursuit of “perfection” in which shifting an entire window over by a few bricks was a necessary decision.

Brick tuck pointing is really difficult to achieve – many factors go into making new mortar joints between bricks blend seamlessly. I love how this relates to visual slip/glitches in codes the same way weavers can “read” draft structures (and moments where those structures might be disrupted) by studying the particular ways threads lay over each other to form cloth. Because all these processes rely heavily on mathematics, any thread (or code or brick) out of place can be glaringly obvious.

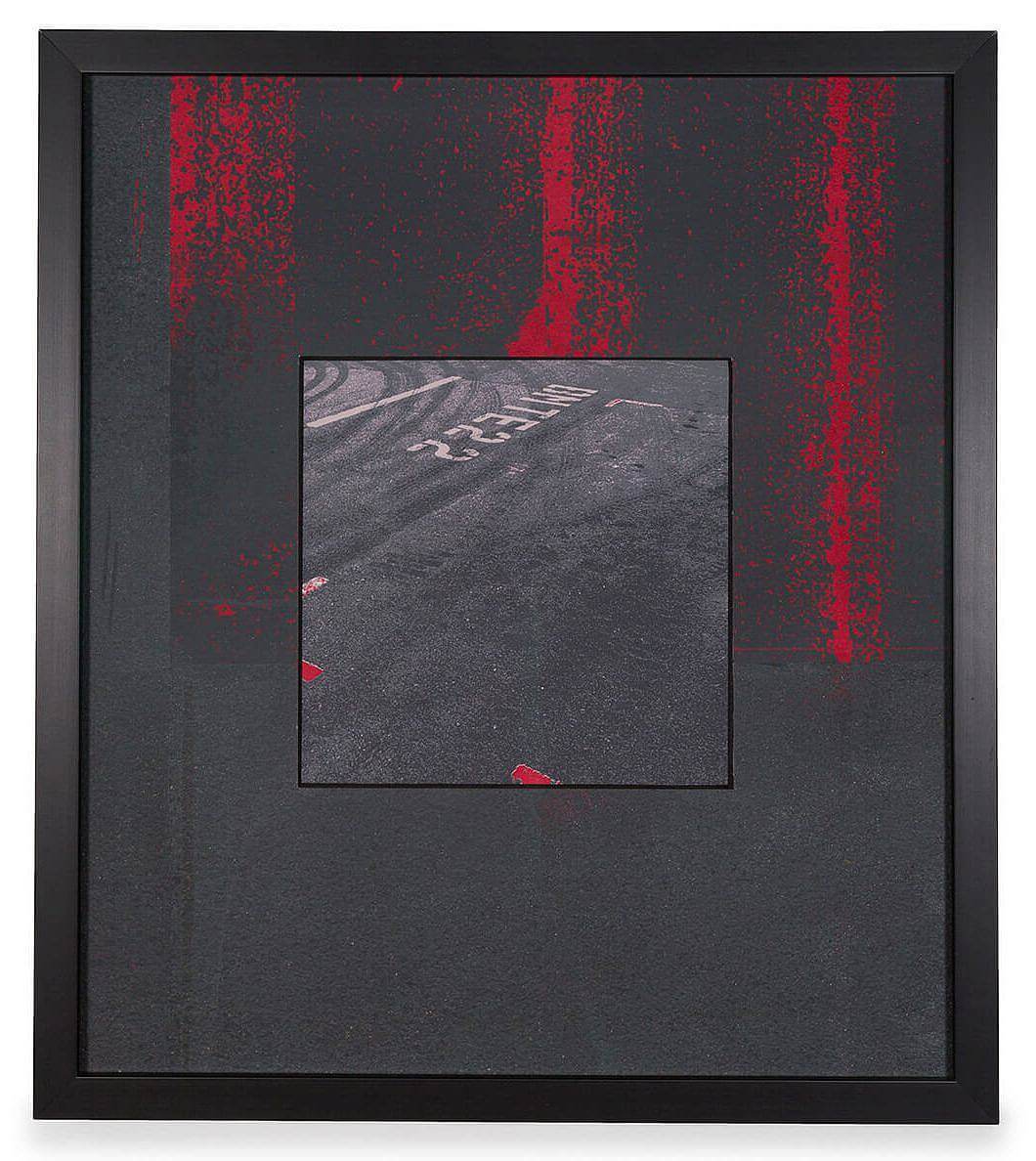

My favorite example of architectural scarring, though, would definitely be paint patches! I take a lot of humorous joy in noticing the sloppy and quick graffiti buffing that’s very prevalent on Chicago buildings. The brown paint used to cover up spray-painted gestures rarely ever “returns” the facade back to the unmarked surface it was, which, for me, signals a lack of fidelity to the original surface and negates the redaction in the first place. But perhaps it’s that ugly gesture of authority, which signals whose voice is allowed to exist in public, that is most interesting to me.

These days I’m not particularly interested in Italian mathematics, though my first entry-point into thinking about undercurrent architectural narratives began in the European Art canon. But this attention to space and palimpsests grew steadily through my trips visiting family in cities across China and the US; observing both rapid spatial development as well as debilitation over a decade. The evidence of how communities build, maintain, and occupy space often gestures toward larger conversations of power on an international scale.

Your work thematically deals with ideas of public space, how has the pandemic/lock-down and subsequent shift away from public space to private space affected your work?

It’s both peculiar and unsurprising that observations I had been thinking about pre-pandemic just heightened rather than shifted or disappeared. Codes of authority (taped off boundaries, traffic cones directing and shifting space in parking lots that were turned into testing grounds, entry/non-entry signs, etc), business shuttering (widespread vacant window fronts barricaded with spray-painted plywood), among many other still-ongoing visual depictions of oppressive public structures and failures. It’s overstimulating and has not lent any “inspiration” to my creative practice. Not that I need it or feel any impetus to make use of it. Perhaps the collective shifting out of the public space has simply made it more relevant to viewers of my work to answer their own question, “Why are we looking at what she’s looking at?”

What role does poetry play in your visual art practice?

I have always had a writing practice adjacent to my visual art practice in the sense that figurative language is usually the immediate material I use to understand my lived experience. Through metaphor, the possibility of a connection between two seemingly disparate elements become sites of discovery. The author Ocean Vuong refers to strong metaphors as “the DNA of seeing,” where one can “enact the autobiography of sight.” How might I draw connections between, say, tire marks in asphalt and skin wounds, that positions something structural as malleable and flesh-like? How does that framework shift the way one conceives of space and objects?

What are you reading right now?

I’m really big on audiobooks since my hands are always engaged and I can rarely sit still long enough to hold physical books open. Poetry, though, must be encountered in phrases/breaths/stanzas so I keep multiple collections around my workspaces to slowly digest over time. Currently:

- Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi

- Losing Miami by Gabriel Ojeda-Sague

- How to Pull Apart the Earth by Karla Cordero

- Love and Other Poems by Alex Dimitrov

What is your studio space like?

I just moved into a new studio at Mana Contemporary Chicago two months ago! I am very fortunate to work out of a space that is separate from home. I am not a homebody at all, so I have had a really hard time meshing any kind of non-rest activity with my home space. My cat, Tofu, also grew sick of me around all the time – I think it threw off his circadian rhythm because he’d wake me up every few hours during the night or yowl restlessly throughout the day. We’re both sleeping better now that I’m regularly away at the studio.

I share a studio with Aubrey Pittman-Heglund and Louisa Zheng. Shared studio space is really important to me; even when I was working out of a home studio, I’ve always been intentional about cultivating an environment of reciprocal, constructive, and collaborative energy. Something I missed about art school is the camaraderie of working on independent projects in the same space.

Have you seen any recent exhibitions or artwork you really enjoyed?

- Mie Kongo’s solo exhibition “Correspondence” @ 65GRAND

- Soo Shin’s solo exhibition “The Body of a Dreamer” @ Patron Gallery

- SarahNoa Mark’s solo exhibition “36° 15’ 43” N 29° 59’ 14” E” @ Goldfinch

- Xindi Tong’s Glaze Paintings

- Aguyoshi’s site-responsive choreography

What is LMRM and how did it start?

I know and admire SO MANY fiber artists in this city but Chicago has yet to house a fiber studio where artists have a touch point to access quality equipment and community support with minimal barriers. For example, there are so many affordable print shops and sculpture facilities supporting sustained artist practices, but we have yet to see one that is specifically geared toward fiber artists (separate from education centers and residencies). I think Chicago really needs one. LMRM (loom room hehe) is a teeny step toward that vision.

In 2020, I acquired two floor looms through microgrants and crowdfunding to prioritise a studio space where I could rent out these looms to artists who have not accessed such equipment because of the financial inaccessibility of owning one.

LMRM is at a nascent stage so I’m flexibly experimenting with a project-based submission request form and sliding scale loom-rental model. It (hopefully) maintains a person-to-person relationship and also allows for artists to access a loom for large and complex projects at varied financial capabilities, whilst also respecting my labour behind making this resource available.

Are you working on anything now?

I’ve been tinkering away at a poetry manuscript for almost two years at this point, one that I have to take long breaks from between drafts (which is part of the work!). I’m looking forward to a May weaving residency at Praxis Fiber Workshop and am elated to finally weave on a computer-assisted jacquard loom for the first time in years and will be preparing for that. I’m also working on collaborative print projects for a forthcoming two-person show with Farnaz Khosh-Sirat at Spudnik Press Cooperative. It also opens in May 2021, so my project schedule feels pretty chaotic right now…juggling! Otherwise, consuming copious amounts of Chinese TV dramas to cope in between the days.

Interview composed by Maddy Olson, Ruby Tresch, and Sam Dybeck.