Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

My name is Derrick Woods-Morrow. I want to say my artistic journey began in a cornfield somewhere daydreaming about escaping the planet or something like that. I grew up in a place that was a very small, country, and “unwelcome” flags flew around my elementary, middle, and high school. I hardly knew what it all meant at the time, but I always told my mom I wanted to be an intergalactic space robot, who fought for justice, had superpowers, and could travel whenever he wanted – far from Brown Summit, North Carolina, the small country town, right outside of Greensboro, NC, where I grew up. My mother never told me I couldn’t be that, between her and my grandmother, they really never told me I couldn’t be anything, ever, and I think that’s honestly how I became an artist. At the moment, I am trying to embody this type of thinking more in my art practice, and delimiting what it can be. Whereas I used to primarily take photographs, I currently see my practice as interdisciplinary and rooted in questions of co-performance, ethnography, and access to leisure through a variety of artist processes.

What originally brought you to Chicago? How has the city shaped your work?

Thank God for Chicago. I came here to start graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and to learn about myself. Soon after my understanding of how Queerness could manifest a reality for alternative family structures took hold of me, and I’ve been leaning into developing relationships with artists in almost a polyamorous way. This has helped me develop languages around intimacy and non-ownership mechanisms that have allowed for collaboration in my work in ways I couldn’t have fathomed before coming to Chicago. It has also allowed me to explore my sexual kinks, have difficult dialogues around consent, and bring these types of questions into my own work. When I arrived in Chicago, I had come from athletics, and played college basketball, and thought the step I needed to take was coming out, when really it was just making space for myself to exist without the weight of having to explain my personhood through my racial, sexual or gender identity – something both graduate school and the north side of Chicago constantly asks of Black Folx.

30” x 40”

Can you tell us about the collaborative aspects of your work?

I am often trying to figure out what is the most equitable way to go about my process of exploring and talking with QBF. They deserve credit in some way for the knowledge we forge. Even in collaboration there needs to be compensation, and so I am now trying to make sure whenever there is a dialogic exchange, that each party leaves feeling full. I often think of currencies falling into categories of mutual aid, exchange, and transaction. I am trying to talk about processing existence in a shared form as the work.

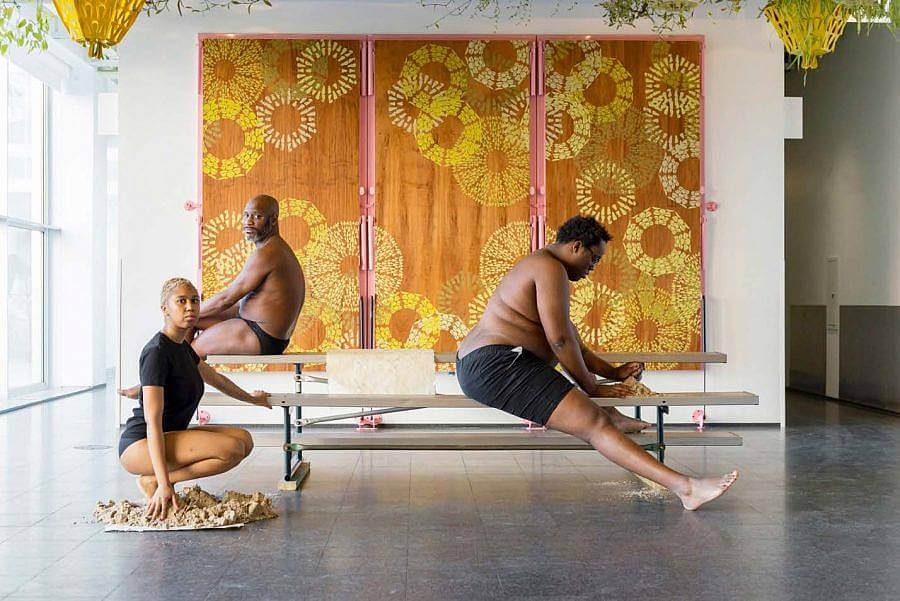

Box of 24, curated by Darryl Terrell, included processes of solidifying these histories through material transformation and performance. Can you discuss this work a little further? How was it to create work for a hotel room?

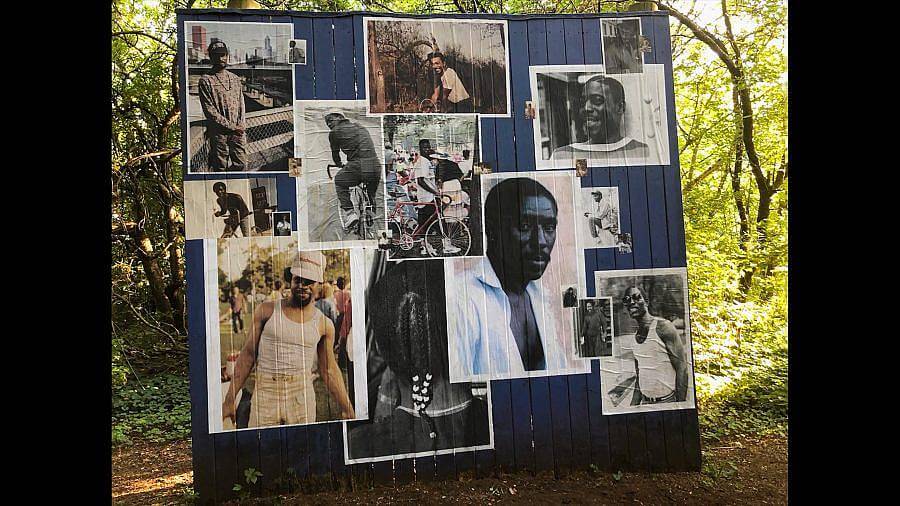

Ah Darryl! I love Darryl. Thats my sister, my love, my headache, my laughter, and my friend. Darryl is special to me. Darryl also told me putting sixty-four bricks on display in the hotel was a bit much, so we went with 24. First Off, I love installation, so a hotel room sounded great. Second off, I spend a lot of time in sleazy hotel rooms seeking anonymous sex from random strangers [I’ve long wanted to do a performance about the visual components of labor, and sexual economy, for folks who would rather have sexual intercourse for 8 hours a day, than a traditional work day – I know many people who would – me included] Box of 24, was not at all this, it was almost the opposite. By no means was it docile, or without a heavy amount of labor, but it was calming. It was a celebration of black rest, of the erosion of time (There was sand, lots of sand that I had excavated from southern beaches and brought to the hotel) and there were images of black people resting, and playing, exploring, and existing throughout time. I wanted to put in motion a reclamation of our time, and the erosive and soluble quality of sand, accompanied by sonic performances that had happened elsewhere in the south, in Chicago, at home in North Carolina, also filled that room. Part I. Part II

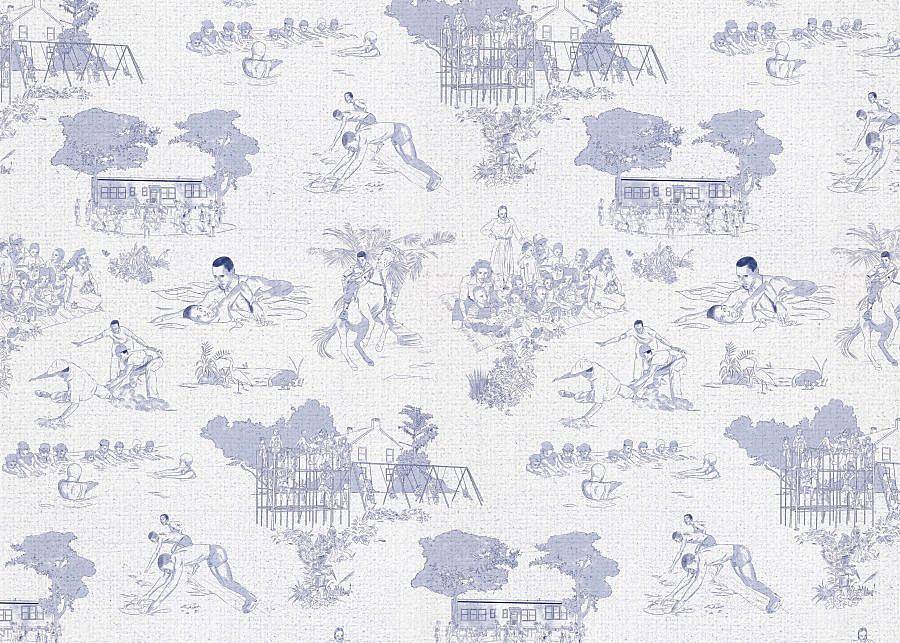

How much of your source images and materials are pulled directly from your own personal history? How much are they pulled from the collective histories of black and queer folx more generally?

A bit of both honestly. Friends, Queer – Kin, Lovers, and many of my relationships, come into the work. Affirmation matters. And so I am seeking to acknowledge our histories as youth sexual explorers, the freedoms, the trauma, and the places we commonly occupied with folx our own age. Society asks us to construct ourselves around something alien to our bodies. I’m trying to have the dialogue about just how early this started for me, and others. I am so thankful that younger generations are finding it easier to exist openly without those constraints, and so oftentimes I collide history, with what I see happening now, in hopes of thinking about our futurity. In an anthropological fashion, I mine our collective conscious asking other Queer Black Folx (QBF) to bring their subjectivities into my work, but at the same time challenging any notion of monolithic black experience. This ultimately affirms our mutual existence, and plays a type of duality, but also individuality. Black Folx have been, and will always be, consistently adding to the history – ‘the lexicon,’ have consistently navigated sexual persecution, a lack of government support, and here we are, and there will BE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.

What is it about performance as a visual language that most interests you?

I often think of everything as performance, as content or material, and at the same time, context, language, and the textural quality of existence – experience. Performance interests me because to be called to action or inaction is the root to our existence. We are either able or unable or somewhere in-between. I am exploring what it means to perform for each other, as each other, collectively and individually for QBF.

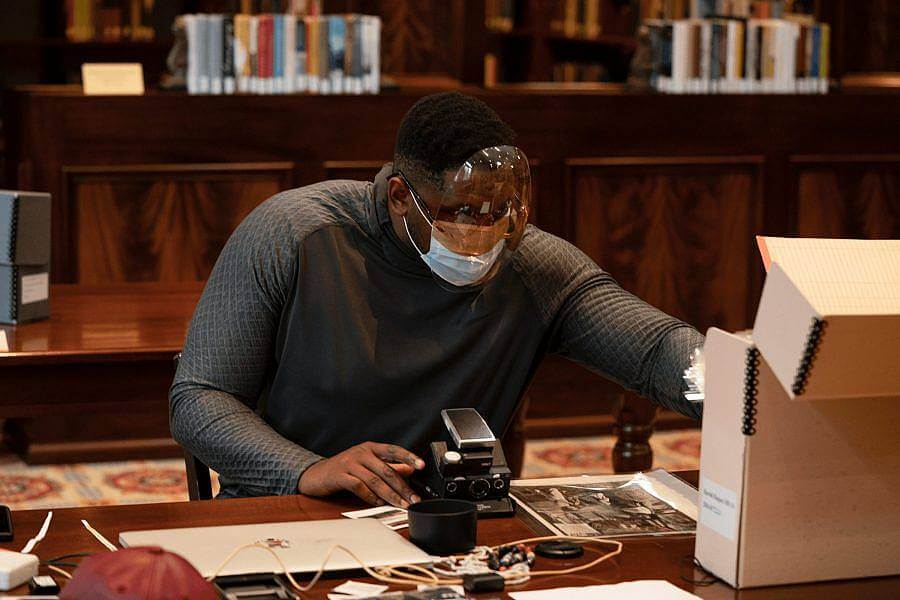

How did you conceive of Much Handled Things Are Always Soft commissioned by Visual AIDS?

I remember watching Barry Jenkins’, Moonlight in 2016 and feeling as if that story was so important, and yet it didn’t explicitly explore sex. It felt phobic in some way, given it was a Hollywood film, and it was widely accessible to an audience other than QBF. I wanted to add something to the dialogue that gave voice to our distance from still being able to talk about sex [specifically BLACK SEX], and the intergenerational question of where our kinky black polyamorous sexually fluid daddies-gran daddies are … we lost so many of them to the AIDS crisis. Such ruminations had been discussed for cities like San Fran, New York, but not much about Chicago, who had so much to do with generating information during the crisis and has had such a lengthy battle with HIV education. I made the film to add to the dialogue, and I wanted to shoot it beautifully, but it also needed to include sex scenes, but it was not my place to tell that story so the person narrating the story was a survivor, collector and photographer, Patric McCoy – he had lived through it, and documented it, and it felt right.

Has your practice changed at all as a result of the pandemic?

I am pushing through and using the tools at my disposal to think about digital sexual economies, alternative methods of relationship building, and abstracted forms of kinks and intimacies. I feel as though I am taking the pandemic seriously. I am trying to keep us safe. My gloryhole is showing up more and more in the work. Questions about the Onlyfans / JustforFans infrastructure, and masked pin-ups seem to be an obvious next step.

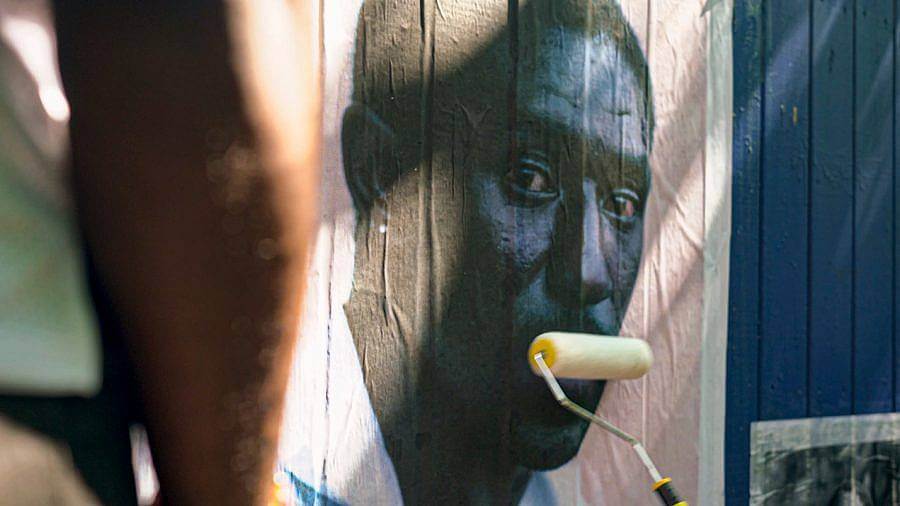

What have you been working on since arriving in New Orleans? What’s next?

I’ve started the process of housing a project here that extends to all the surrounding areas, the 16 states that make up the American South region. In the project, I am meeting black folx, and asking them to share their stories, affirming our shared experiences of growing up in the south, filming small vignettes of queer black communities, dialoging about sexual health and sex, in order to develop a multimedia film installation, with audio components, photographs, and garments. I am also writing some poetry around my intimate encounters, considering how sexuality & sex are operating differently for most of us during the Covid-19 pandemic, exploring what sexual exploration at a distance may look like – kink, digital sharing, and alternative methods of connection for black folx in the south.

How do you take time for yourself when you’re not working?

I take days off, full weeks off sometimes. I smoke a healthy amount of ganja. I laugh and cry more now. I masturbate and take moments to seek pleasure. I let myself fall in love, and out of it. And I try to give as much as I can of myself to QBF that I care deeply for. I center my alternative families, and I understand, now more than ever, giving people space and being empathetic towards other situations during this time is so important. We are all living through a pandemic, and dealing with many new traumas, many unknowns, and that’s alright – I’m rooting for us.