Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

I am a visual artist who was born and raised in a rural part of New England, spent some time in Boston, and now has been living in Chicago since 2014. The work that I produce consists of sculptures, works on paper, drawings, and paintings. At its core, my practice is a tool for discovering new ways to better understand the material systems that constitute contemporary life and to question the spectrum between the built environment and facets of queer identity.

Do you have any upcoming projects or shows?

I have a lot of things in the works but nothing set at moment, so keep an eye out! I also currently have a piece going up at the (COVID-postponed) Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and opens the first week of October.

What impact has Covid-19 had on making and showing your work?

Like many others, Covid-19 hit my studio practice pretty hard. Just before the onset of the pandemic, I was finishing up a new body of work to be shown in a two-person exhibition (with Chicago based painter Clay Mahn) in a gallery in Montréal. We were both in those last critical stages of working, just before packing and heading up north to install when the U.S shut down and the borders closed. Needless to say, this project and the conversation between Clay’s work and my own still remains up in the air.

I also did not have access to my studio for the majority of this past spring/summer as I was back on the East Coast. Although I was spending most of my time outdoors and helping family, I was able to think through some new ideas and experiment with some materials. I am currently jump-starting and regaining lost momentum back in the studio here in the City and have some projects underway, which feels good.

Yet however difficult the impact of Covid-19 has been on making and thinking about work in general, it has also presented other opportunities for introspection and time to just slow down, which I didn’t realize I needed. I am also more open to alternative ways of showing my work outside of the physical gallery than I have ever been because no one should have to take any additional risks while we still have this ripping through our communities.

How have you adapted the formal language of minimalism, an art movement often associated with institutional power and hyper-masculinity, to critique systems of meaning?

I think I inherited the vernacular out of a process of material understanding and have employed visual cues in past projects to leverage and discuss other pressing concerns; as an act of subversion. It’s the distilling truth process, sense of autonomy, and visual austerity that I grapple with and find useful to edit, stress, and complicate. I use to think that materials remain as materials in the process of making and in a way they do just that; but they also transform, change, and become unknown. I could also stand to mention that any visual echos that reference this past art historical movement could open up new forms of representation through abstraction and ways to relate and cope with our exponentially exceeding excess culture, but, I’ll save that for another conversation.

How does using objects that directly reference cartesian measured space, i.e. rulers and measuring tape, contribute to the discussion on constructed social space?

The “(flexible measure),” works incorporate rulers and measuring tapes are often polished in some way or another and range from mirror to a mat finishes. This process of removal is also a process of refinement, and also compromises, yet reifies these objects themselves as tools and units of measurement. They remain a footnote to a constant or a physical reminder of dimension and proximity that we all can relate too. Yet, these works bend and push back once reflecting and activated by the viewer; offering the potential to relate to a less rigid set of constructs in terms of material, space, and time. These works also remain suspended between material object and image and oscillate questions regarding functionality, utility, and of use-value.

What is your intention in transforming found objects?

So, there are many different reasons why I employ the materials and objects that I do. Some objects are pursued for specific projects, others are tripped over and in some ways unveil themselves. Regardless, there is a one-to-one relation when employing found objects which I find useful. This directness comes from a shift in the context which allows for a tethering of value systems, material histories, language, and other narratives. These material objects already have a solidified purpose, a place, and time, and I am interested in jostling, editing, and shifting those relationships that allow for new definitions to surface. The transformation process

happens as soon as we forget what we are looking at.

During your 2019 interview with Joe Brommel for Wassaic Project, you discussed an intended shift from found objects towards a further investigation of making. How has this manifested in 2020?

Since my conversation with Joe last summer, I have been testing out a few different materials, doing a bit more free-hand drawing, and reconnecting with the processes of printmaking. I still have been making the work that I do. But, reintroducing my hand through fabrication techniques and image production still remains at the forefront of my mind. This is to complicate and balance out my own ideology in terms of making and thinking, and to throw some new things into the ring.

What are the implications of failure within your “(edit, revision),” series, and your work as a whole?

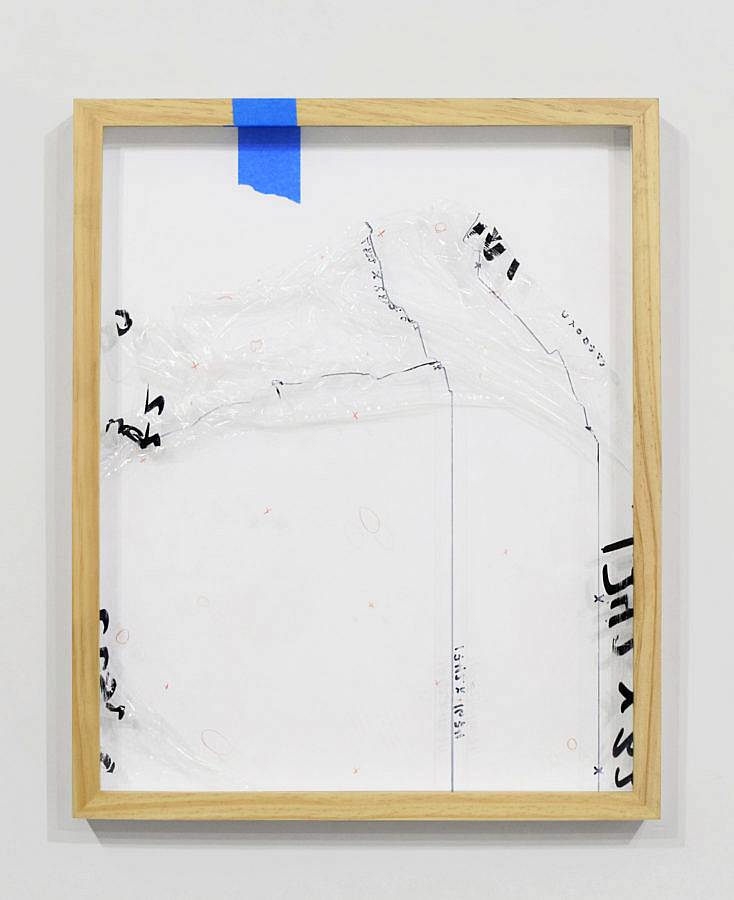

So the “(edit, revision),” series is an ongoing project and collection of drawings that are created by framing plexiglass and the protective film at various stages of removal. The film has dimensions and markers for a hypothetical plan in sharpie, as well as, notes in colored marker dictating material discrepancies caused by shipping, handling, and studio storage. The works convey the process of making a drawing for display with the conventional framing techniques and materials. The act of semi-removing the interior film compresses the drawing of suggested notes and measurements; solidifying the gesture, notation, and materials as an image in the process.

The works in this series are in a way self-reflexive and are loosely looped within a system that they present. The line drawings and numeric codes on the films read as conventional notations that point to another material project. They slip in this fictional state and then are re-interjected by a real physical moment of touch which compromises the image over a material flexing. The numbers are also not actual dimensions (but, then again sometimes they are) and range from past phone numbers, addresses, and other arbitrary sequences that I find. I have also been applying blue painter’s tape to the frames, spacers, and backings of recent works in this series. The tape adds a flash of color and a sense of immediacy, a quick fix to an unforeseen problem, yet is foiled upon closer investigation; from afar, the pieces of tape read as one continuous piece but are in fact multiple with slight misregistrations. The failure in this series is plained as to open up for elements of chance and more flexible outcomes. And, I think that my work in general often starts and reflects similar situational hick-ups in systems; either factual, perceived, or otherwise.

How has living in the urban environment of Chicago influenced your practice?

I have always pulled inspiration from my immediate environment. Either in a physical sense, through materials and objects, or other experiences and observations. I am not sure what that type of sensitivity is called. But, my work did shift when I moved out here. Before, I was making sculptures and installations out of discarded building materials from construction zones throughout the City of Boston. My work also revolved heavily around printmaking (primarily intaglio) at this time, and I was pulling prints that in some way reference these material sites, the state of flux dilemma, and the process of printing itself.

When I came to Chicago my work became more specific in terms of the infrastructural and sociopolitical systems that I was tapping into and material objects that I was employing. For example, the first sculpture that I made when I moved out here incorporated a city bike rack and the remains of my bike after it had been stolen which was still U-locked in place. Together, this displaced assemblage was a focal point for an installation titled, (<<) from 2015 and stood as a model into questioning the meaning of exchanged value and the context of material circulation itself. Everything else seems to quickly spiral outward from there. At the end of the day, Chicago is a good City for making, there’s a lot of people, available space, and a surplus of materials lying around; all of these in which gets folded back into my work some way or another.

Can you tell us about your recent series of work where you’ve been using focused sun-light?

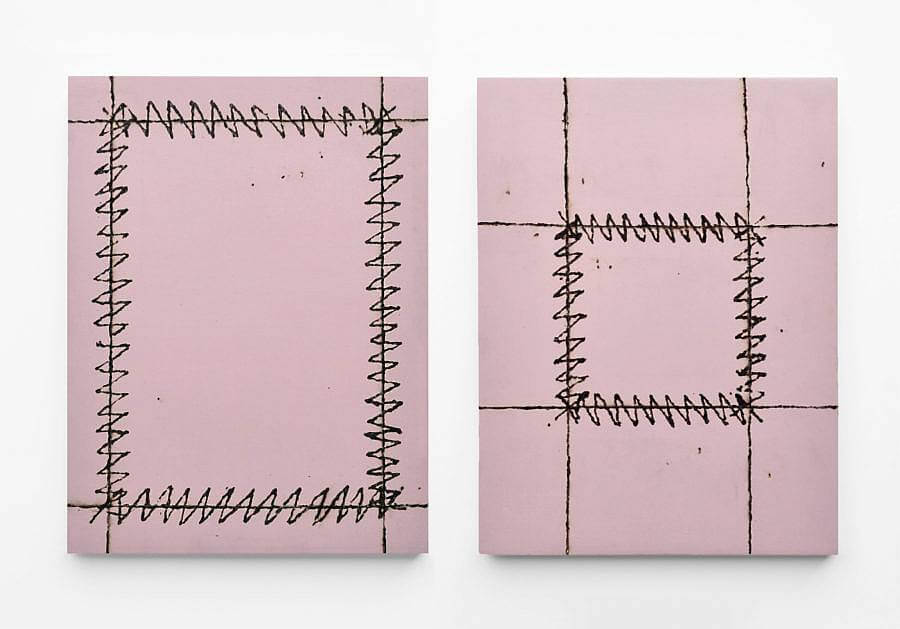

I made “(invisible grid 1-2),” over this past summer during the quarantine. The line drawings are burned from focusing sunlight with a magnifying glass and reference a basic zig-zag pattern; similar to those used in basic welding techniques. At the time, I was actively thinking about ways of using color more explicitly, and in relation to this gesture and process of mark-making. It resulted in this somewhat highly specific gray- pink color that sits between pink insulation foam, the 1977 album cover of NEVER MIND THE BOLLOCKS here’s the Sex Pistols, and the pages of BUTT magazine; a gay publication/platform that started in the early 2000s. Of course, there are other references and connotations to this color folded in there as well, but these three really solidified the diptych as to interweave labor/fabrication codes and processes with subcultural and homosexual markers with the focused energy of the sun. These two works are third in a new series of paintings that follow the same process of harnessing sunlight as a tool for image production

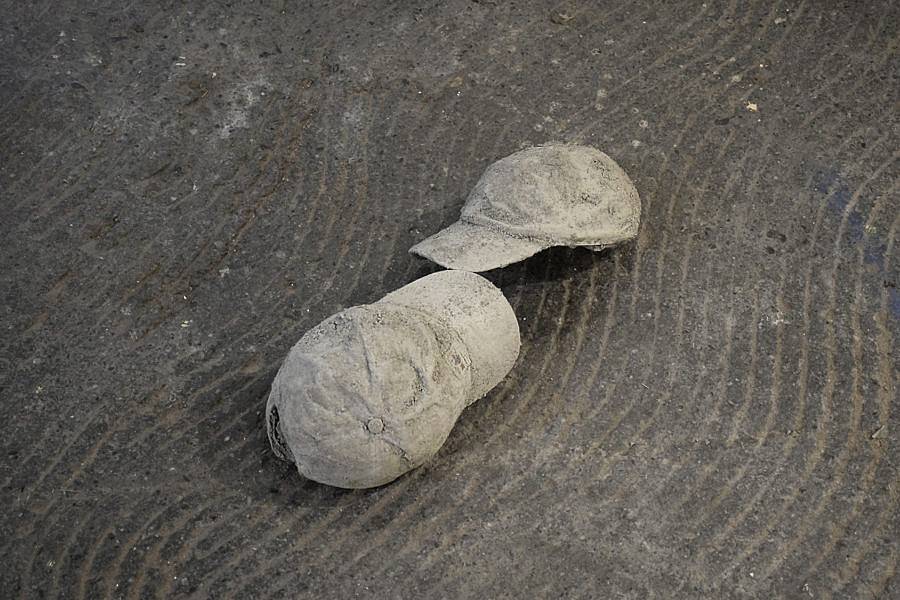

In, “Carhartt hat arch,” 2019 you create an intimate scene where you use concrete to kiss two Carhartt hats together. Can you discuss how this work and others in your practice reflect an investigation into gay-specific masculinity?

This is a relativity new thread of inquiry in my work, and I am still in the discovery phase of tracing the lineage and what it means to do so. But, I am starting from my own experience and how I personally navigate these spectrums; and some of these early works reflect that.

But for some context:

When I was a kid (up until my mid20s) my family would vacation in Cape Cod Mass. every year during the same week in July. On rainy days we would head up to Provincetown to look at boats, shop, eat, and visit the Whydah Pirate Museum. Although unintentionally, the time we would be in P-Town was also always during Bear Week; I couldn’t tell you how many parades that equates too. But, I acknowledge that over the years and even from the sidelines that I grew up with this understanding and perception of what queerness means and what it looks like to be a gay man from this proximity. This forged definition was born out of this type of hyper-masculine specificity (that is more open and fluid today) but one that I can still relate back too.

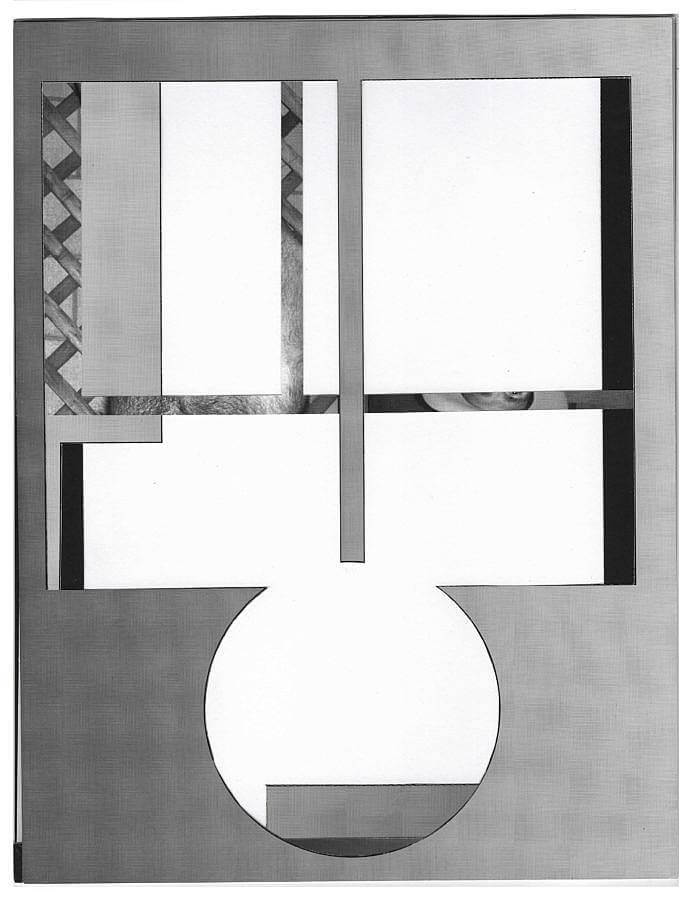

I am trying to figure out why. So, I have been collecting American Bear magazines from the ’90s and reading them and producing layered collages out of the photoshoots. In “(Max, Denver, CO),” 2019, I cut out the images of the subject leaving just the borders and margins where an individual reader is intended to hold. The cutouts are then layered on top of one another, with some pieces reversed between layers; allowing glimpses of the body or the architectural set to surface. This series places the male figure in the forefront, but without the body, and with only minimal hints of codes and signifiers. There is also a shift in subjectivity that occurs with these pieces that I find interesting. The shift is from the super focused and fetishized figures in the photographs to those who have made physical contact with the pages up until this point in time. This collage and others like it will be paired with drawings and writing in a printed publication format to come.

So with, “(carharrt hat arch),” 2019 the two hats were filled and dipped into concrete and allowed to dry in tension to one another. Once dried these two hats support each other’s weight by the tip of the brim, creating a completed arch. This embrace of a contemporary “rugged, workwear-inspired apparel” brand conveys a possible gay moment of touch, and a concrete model of an architectural form that is dependent on one another; producing a hyper-masculine loop of object, form, and material, foiled by care, tenderness, and sexual desire sameness.

Interview composed by Amanda Roach.