Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do. I’m from a really small town in central Pennsylvania, a place where conservative, religious, traditional family values are placed above all others. If you deviated from those cultural norms, you were treated as a pariah, a herald of immorality. In my hometown, my sexual identity was merely a role which one could “perform.” As a young gay boy, I was forced to conceal my authentic self from my friends, family and peers, which left me with severe feelings of alienation and guilt. When I entered college at Penn State University, I started questioning why the world was the way that it was, so I began combining larger ideological issues with my natural facility for painting. I then did my graduate work at the Rhode Island School of Design where I received an M.F.A in Painting in 2016. Beyond that, I teach drawing and painting at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University.

What is your process like? Do you work from life, photographs, or your imagination? All three. I make a lot of digital collages – taking bits and bobs of imagery to create a scene that seems just out of reality, a quality inherent in collage. I’ll start with a thumbnail sketch and from there I will create these digital composites using this free app on my phone called Brushes. I can sit anywhere and have this really immersive and intimate drawing/collage experience with my smartphone. It’s like my 21st century sketchbook. If I can’t quite capture something, I’ll move to paper and flesh out the details.

From there, I’ll begin the physical construction of the painting. I labor over my painting supports until their polished, high-gloss surfaces resemble plastic or skin. Skin covers our frame, it’s our means of intimacy, and I want the viewer to recall all of the associated fantasies that come with it. The painting is then fossilized in a thin, gloss varnish, illuminated but camouflaged by the viewer’s image reflected in the surface. This illusionism invites the viewer to focus on the relationships between their body and the image. The craft in my process allows the paintings to achieve a certain glitz and vanity, and speaks to my role as a gay man who makes paintings. My devotion to craft can be seen as a type of personal protest: there is a dutifulness and type of social comportment that is not culturally expected of man, but historically has been referenced or attributed to women. Craft, at least on a personal level, acknowledges the complicated perception of my masculinity.

Who are some of your favorite artists? There are a number, but I see myself working within the tradition of the Cadmus Circle, particularly George Tooker, and the Hudson River School of Painting. An artist close to my heart is the immensely underrated Chicago Imagist Ed Paschke. Initially, my love of Paschke’s work was merely formal, but then broadened into an appreciation of the ideas surrounding his work. As someone who feels like he doesn’t quite fit in, I respond greatly to the fact that Paschke often affiliated himself with people on the periphery. He sought living and working situations — from factory assistant to psychiatric aide — that would connect him with Chicago’s diverse communities, as well as feed his fascination for urban life and human flaws. He developed a distinctive language that fluctuated between personal and aesthetic introspection, and a public confrontation of social, cultural, and aesthetic values of the time.

What was the last exhibition you saw that stuck out to you? The Grant Wood exhibition at the Whitney absolutely blew me away.

What’s your favorite thing about living and working in Pittsburgh? I’m a small town boy at heart, but always wanted to live in a city. There is something about Pittsburgh that is both urban and rural at the same time, which is comforting to me. The art community in Pittsburgh is small, but mighty. Many of my students stay here and get cheap studios, honing in their craft before grad school applications. In the age of social media, I don’t have to be in New York in order for people to see my work — my gallery is in Paris, for example. Pittsburgh is a great place to live and work, I feel really lucky to be here.

How did your interest in art begin? Have you always been inclined to paint portraits? I’ve always found this a difficult question to answer because I never remember saying to myself “my fantasy is to be a painter.” I’ve literally been drawing and painting since I was aware that art was made and not conjured from thin air, so that desire has always been a part of me. I can trace some of my sensibility back to the first experience I had with painting. It hung not in a museum, or in a gallery, but in my late grandmother’s house, just above the old rocking chair. It was a painting of my great-aunt Virginia, painted in 1913. It’s a simple image: a beautiful woman, cast in a deep red light, looking gently outside the picture-plane. That particular work informed a lot of my aesthetic sensibility and I’m sure, subliminally motivated me to work with the figure and the portrait.

What is your favorite part about teaching? Have you learned anything about yourself and own practice while teaching? Teaching is a relatively new experience for me (I’ve only been doing it for about two years), so I’m still learning how to optimize my effectiveness in the classroom. I love the symbiotic relationship with teaching; I’m imparting knowledge, but the students are also sharing their insights as well. It’s really important to not let your aesthetic preferences dictate the way you interact with students and their work. I want to be open to all ideas, all formal considerations, and foster my students’ idiosyncratic voices. Teaching is a super rewarding experience and it gives you the opportunity to strengthen what you know. I’m still learning what it means to teach and how to do it effectively. Art education is more crucial than ever, so it feels really good to keep that part of our culture alive in whatever small way that I can.

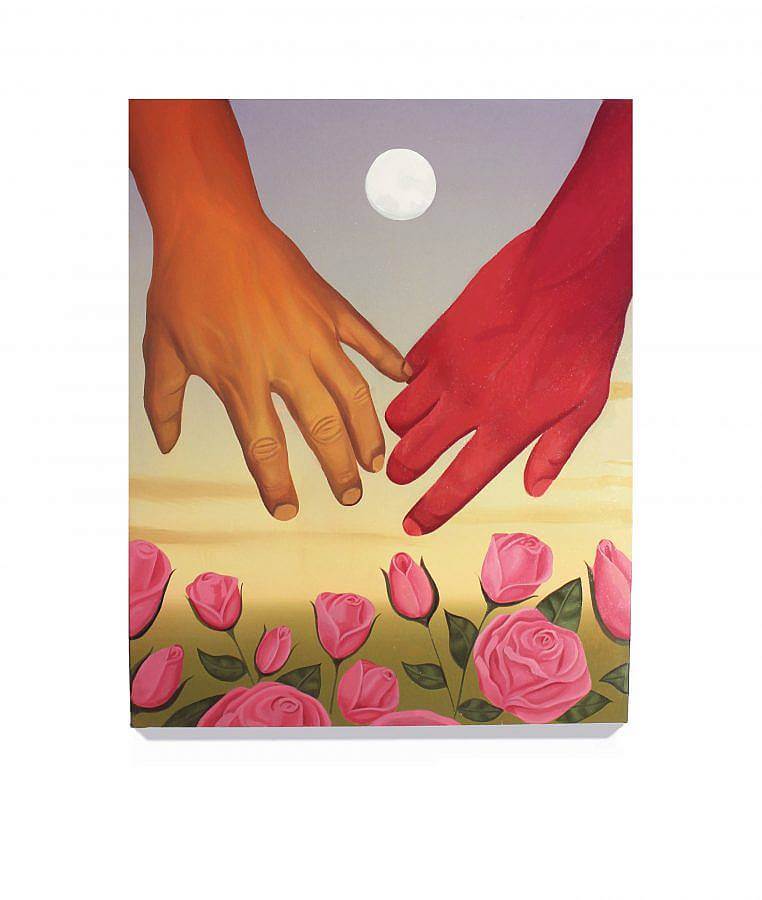

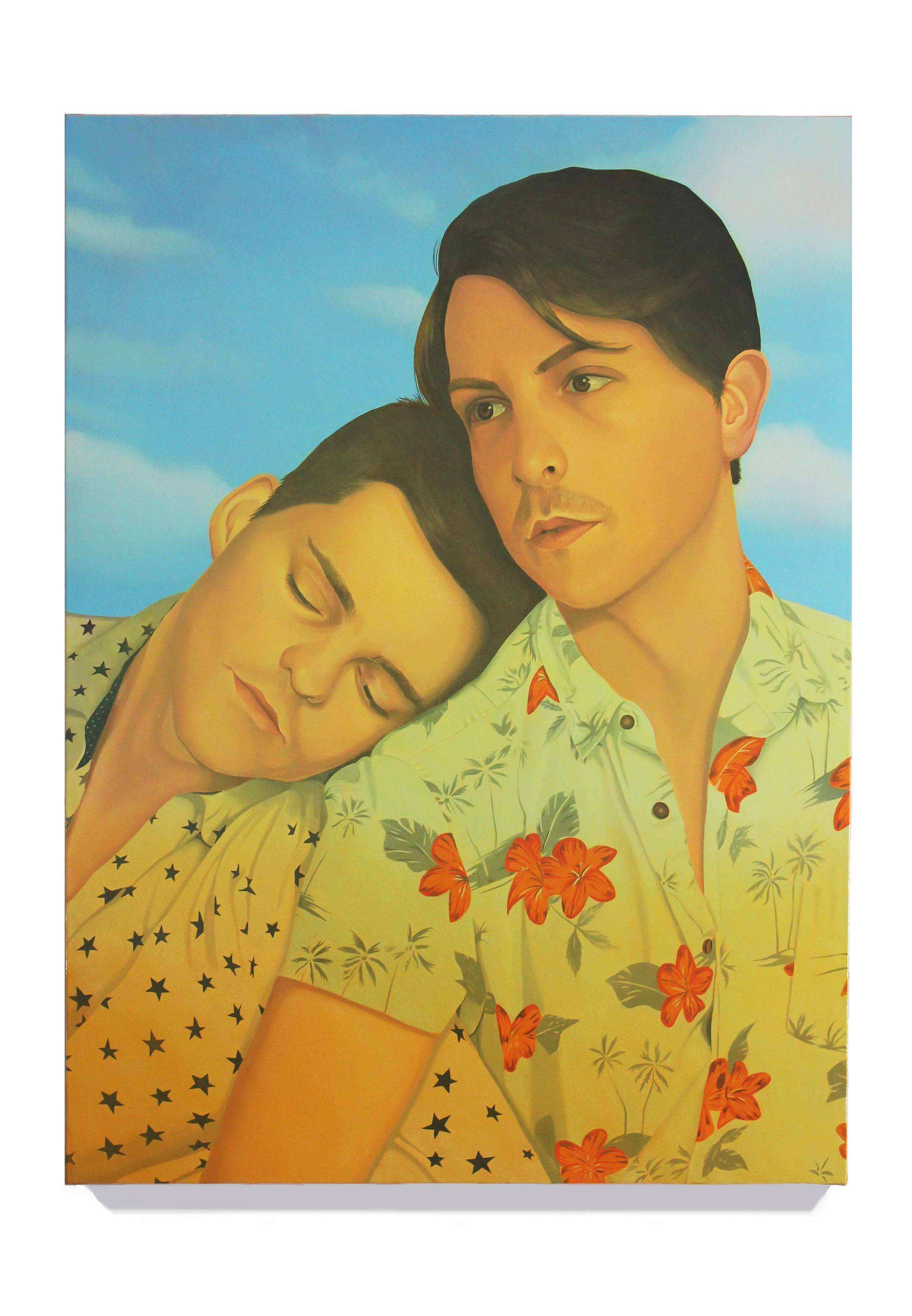

What do you want a viewer to walk away with after seeing your work? There is a canon of creative work that portrays the gay lifestyle as abject. Films such as The Celluloid Closet, Advice and Consent, or Walk on the Wild Side show images of unhappy, suicidal gay men, which magnify the social perception of my community in our culture and fuel a conservative counter-narrative. With my work, I’d like to reverse that narrative and show positive images of gay men and male vulnerability. The greater purpose of the work, as I see it, is to be a space where people can contemplate their own biases and presuppositions, which will hopefully lead to both normalization and acceptance of people who are LGBT.

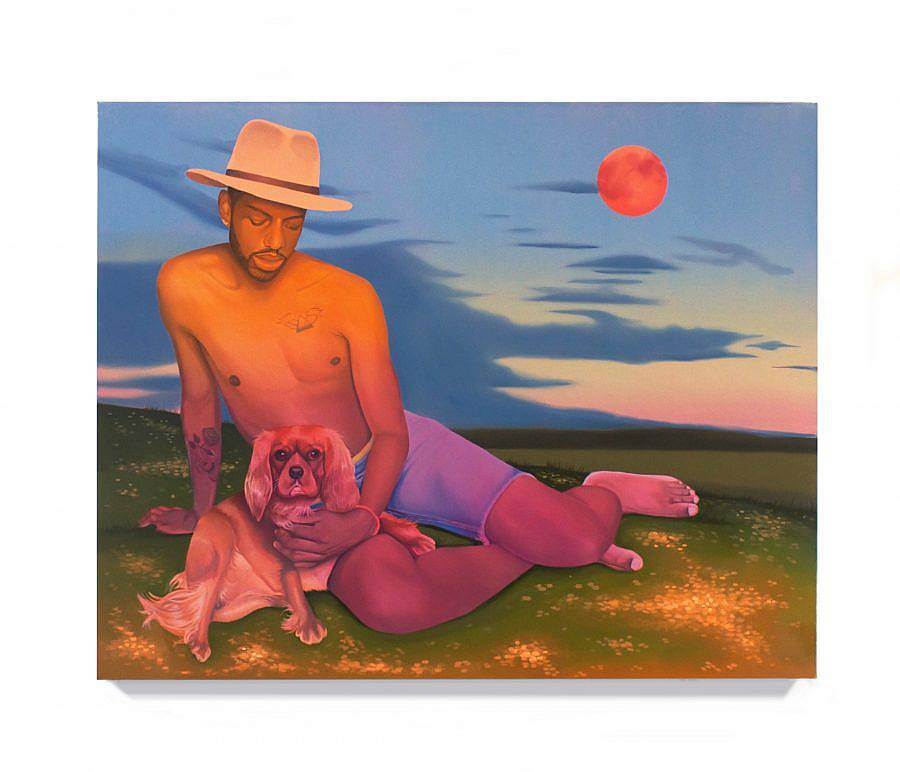

Adam and Fred

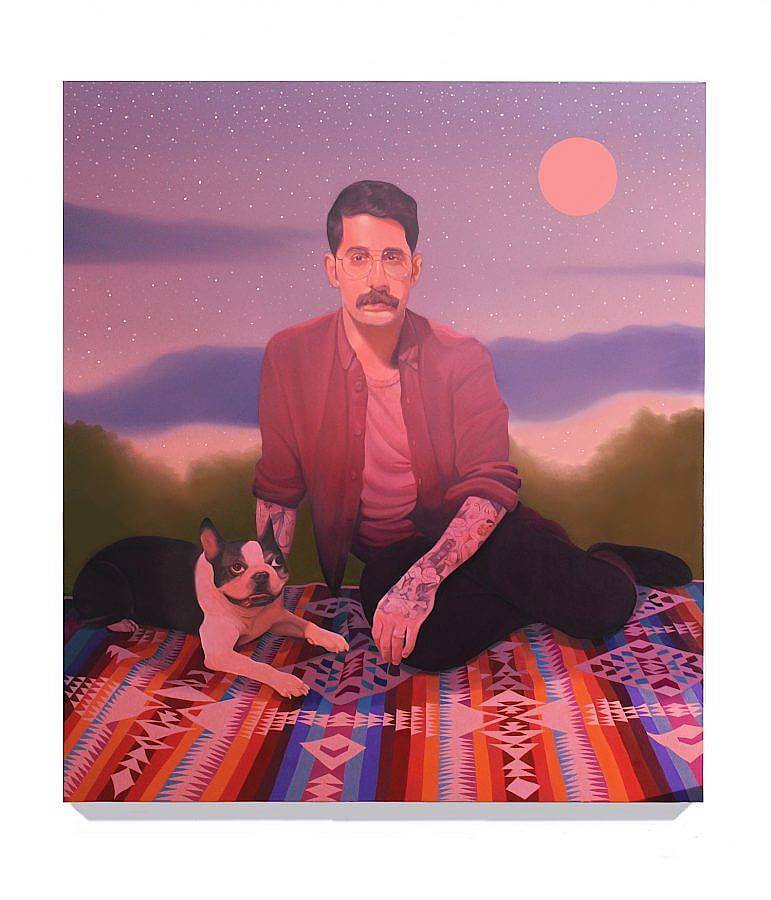

Where do you see your practice going next? Any major changes happening in the studio? I’m not sure where my studio practice will go next as I just began work on a a new series. Right now, I’m making paintings about love — love between two men, love between man and dog, love of oneself. So, I choose the subjects of my painting based on the level of emotional connection I share with them. Generally, the figures are good friends, my partner or acquaintances that I find interesting. I’m also looking for people that have a specific “look,” one that is not co-opted by our accepted rules of beauty, but embody something outside of that convention, which needs to be recognized and valued.

Recently, I have been gesturing to the vast canon of European royalty painting, by blending the epic and banal in painted images of gay men and their dogs. This combination quotes the pageantry of that history — their rich garb and over-the-top landscapes — and in so doing, elevates queer bodies and bodies of color from second class, to royal class. I’ll be showing this series in two separate shows at Galerie Pact in Paris and Marinaro Gallery in NYC.

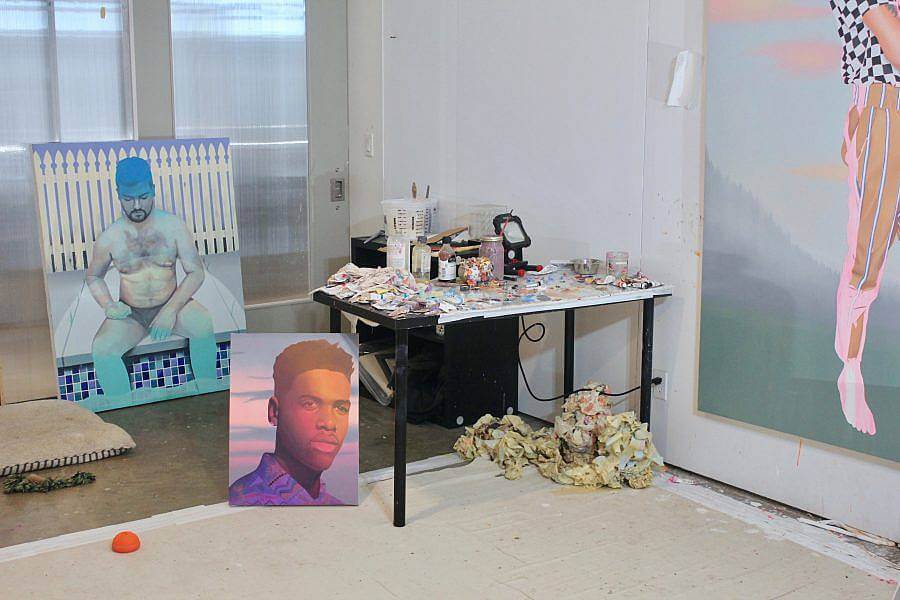

Describe your current studio or workspace. My studio is actually located in a renovated basement of an old church, echoing my childhood growing up in the Catholic Church. It’s a beautiful space, but it might not look like it currently, as my workspace is in the early stages of chaos – half prepped surfaces litter the studio floor, RedBull cans are starting to cover all of my tables and my palette is an absolute mess. With that in mind, I’ll give you a limited view, so I can save myself the embarrassment!