Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

I am a Visual Artist from Bogotá (Colombia), a rainy, semi-cold and chaotic city of 8 million inhabitants located in a 2600 meters plateau, on the Colombian eastern Andes. I lived there all my life until august 2017 when, thanks to a merit scholarship, I came to Chicago to pursue an MFA at the School of the Art Institute. I was raised in a middle-class family, on a liberal, austere environment, in a 4th floor apartment. I attended to a French elementary and high School and then completed my undergrad in a Jesuit University, back in 2006. I have a dog named Doc, which is the short version of “Doctor”. I guess his mayor is in psychoanalysis because he is a great listener.

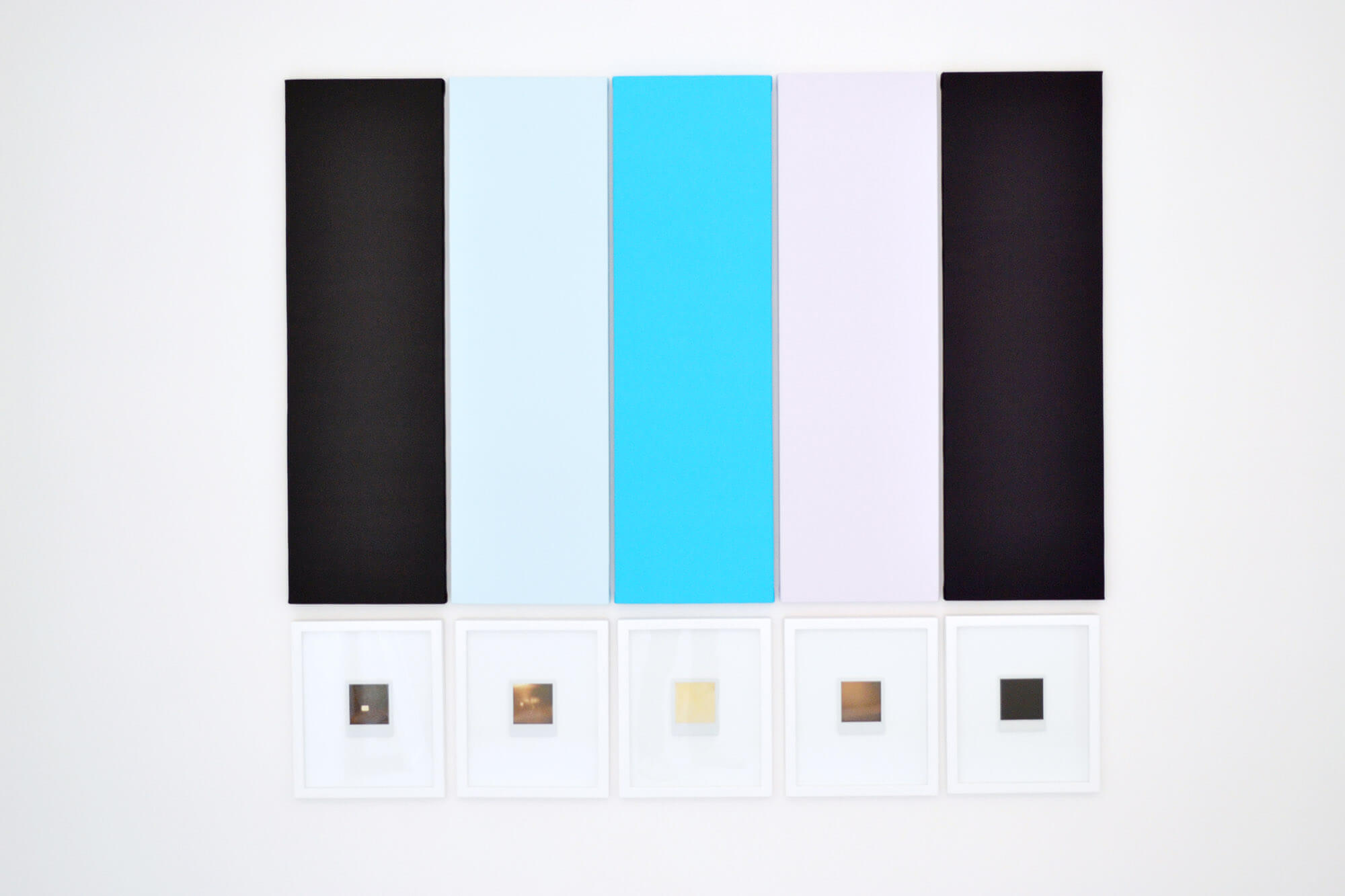

I mostly arrange and order things, I play and transform common objects, I paint carefully graphical shapes on pre-stretched canvas or precarious materials, I write and print short texts, I make mental maps and I plan installations. I’m obsessed with the idea of unveiling the poetry, tensions, systems and structures hidden behind things that might be considered irrelevant, ordinary or mundane. And then, understand how this can reveal complex but unnoticed issues of the absurd world we live in. As for example, analyze the optical concept of myopia to understand classism and political division. Or use a popular game to explain strong gaps between similar cultures, just to name a few.

What is inspiring your practice and material choices right now?

Recently, my inspiration comes mostly from quotidian sources. Like for example the colors of institutional walls, the light projected on a corner of my apartment, the cardboard packages stacked next to the elevator waiting to be collected by my neighbors, something that I’m cooking, the remembrance of a travel, an irrelevant sign on a street, an archive of magazines that my mother collected for 30 years or a conversation with a friend. I try to be attentive, to listen and to detect ideas in places that you usually would not look for them.

Art related, I have been looking closely into the 60’s west coast Light and Space movement. I rediscovered Ed Ruscha, specially his books and movies, as well as Franz Erhard Walther, Agnes Martin, Giorgio Morandi and Mary Corse. Once a week, I take a look at a painting in the Art Institute called a Reasonable Facsimile (1942) by Arthur Dove and I also got obsessed with some slow cinema filmmakers like Tacita Dean, Chantal Ackerman, Michael Snow and Anthony McCall.

What current or upcoming projects are you working on?

Right now, in my studio I’m working on ten 20” by 20” paintings that, stacked, fits in a cardboard box of the same size (20” x 20” x 20”). In two of the exterior sides of this box I will project a narrative sequence of still images which title is “Learning to fly”. In Parallel, for the MFA show at SAIC we decided with 7 other students to break with the individualism of this kind of exhibitions and propose a collective approach to it. We are doing collaborations, documenting the process, having continuous meetings and constantly nurturing the conversation beyond the institutional request.

Apart that I just de-installed a piece at a group show at Lithium Gallery in Chicago, I’m currently participating in a group exhibition titled Cielos (Skies) in an artist run space in Bogotá called Salón Comunal and, in August, I have a two person show in Lokkus , a gallery in Medellín (Colombia).

How did your interest in art begin?

I think that my interest in art has been there forever. I could tell you a story about me drawing as a kid, or visiting an art museum for the first time but, to be honest, I think it doesn’t happen like that, suddenly, even if I love those artist tales. On the contrary, for me is something that you carry with. So, what I can remember from an early age is that I was very sensitive to other people behaviors, I had delirious fictions, I abstracted shapes and colors in my head, I got obsessed with things, like going to a window to watch a train pass everyday around 4:30 pm. I was in another frequency that is very difficult to explain in words and that sounds very cheesy today. But you know, you are experiencing the world in a different manner. You don’t rely in boundaries, categories, norms. You think you have superpowers.

As a profession, I guess it dates back to when I was around 18, in undergrad and I started to read about it, to attend to museums frequently, to see complex cinema and to read contemporary literature. But that for me is just a way to cultivate the other side, which is unavoidable.

What does your process typically look like?

Chaotic in my head and very ordered and Cartesian in the outside. Sometimes I start by drawing something. Other times I record a voice note in my phone. One idea keeps circling in my head while I’m in the bus or in the train. Then, another week I might read a book or watch a film related to that idea. I might do a mental map on my notebook and stick references on the wall. Then I start painting. I always paint at some point. And struggle even if it’s a monochromatic painting. Afterwards I write something, or do a sketch in my laptop. I spend an hour wandering in the studio looking at something and thinking. Then I drink coffee and smoke. I might have a beer with a friend or my partner. No specific order. The only sure is that towards the end there is a lot of handmade involved, hours producing things and then meditative and solitary moments in the space where the work is going to be shown.

You live and work between Chicago and Bogotá. How do these two places influence your work?

Actually, I keep comparing this two places, “The Heart of America” and “La Atenas Suramericana”. They were both settled on top of muddy terrains and share a similar pastel violet in the sky when the sun is setting. There is a lot of grey, brown and orange on the bricks of the buildings. Also, if you overlap the two maps, the structure is similar, they both have a grid, a clear social division between North and South and a natural barrier at the east limit of the city. A lake in Chicago, a Mountain in Bogotá. One could be the cast of the other. By contrast, Chicago is an example of urban and architectural modernism while Bogotá has always been under construction, always dreaming with that modernity that never got executed because of a lack of political commitment and unclear long run plans. All of these reflections are embedded into my work. A mix between precariousness and sharpness, strong institutions versus informal endeavors, rigidity and modularity, what could be and never is.

What was the last exhibition you saw that stuck out to you?

Renaissance Society’s Also on View by the Croatian, David Maljkovic and curated by Karsten Lund, is still resonating with me. In this show, the curatorial challenge was to bring together a variety of works that were originally displayed within another context and in previous projects of the artist. It’s like organizing a conversation between people that have things in common but haven’t met before. So, the Exhibition itself becomes the medium or the format. And that for me generates such appealing tensions, between form and meaning, between the digital and the analogue, between scales and materials. Altogether, the show possesses like a squeaky sound. One very similar to the cricket that you can actually hear in the piece titled A long Day for Form.

What have you been reading recently?

In February, I finished the book Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees which is a conversation for over 30 years between Robert Irwin and Lawrence Weschler. Now, I’m beginning the counterpart of this one, True to life, which is a similar conversation but with David Hockney, who disagrees with most of Irwin arguments on vision and perception. I also finished a wonderful book by the Colombian writer Carolina Sanín called Somos luces abismales. It’s amazing. For me this is the kind of unclassifiable text that is closer to contemporary art than to literature. I have also been reading some stories by Antonioni in his book That bowling alley on the Tiber and Pirates and Farmers by Dave Hickey. At night, when I’m not too tired, I try to advance with 4,3,2,1 by Paul Auster.

What do you want the viewer to take away after viewing your work?

First, I want people to increase their sensibility towards their surrounding so that they don’t take anything for granted. I also would love that they start reading between the lines and understand that behind the visible structures and systems that we see, as with my work, there are complex layers and nets of meaning. Usually, behind what seems common and apparent there is also poetry, humor, cynicism, uncanniness, nostalgia, fear, criticism. It’s a matter of perception and deep reflection. Finally, I also want people to get a sense of detachment (in a philosophical definition) and boredom. Getting used to boredom might be a key for the future. We are way too distracted right now.

Do you have any plans for post graduation?

Yes. One of the most cliché one. I am going to rent a car with Julia, my partner in crime, and we are driving to California. After that, I am not sure. Many things are probably going to happen but I’m embracing uncertainty right now.