Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

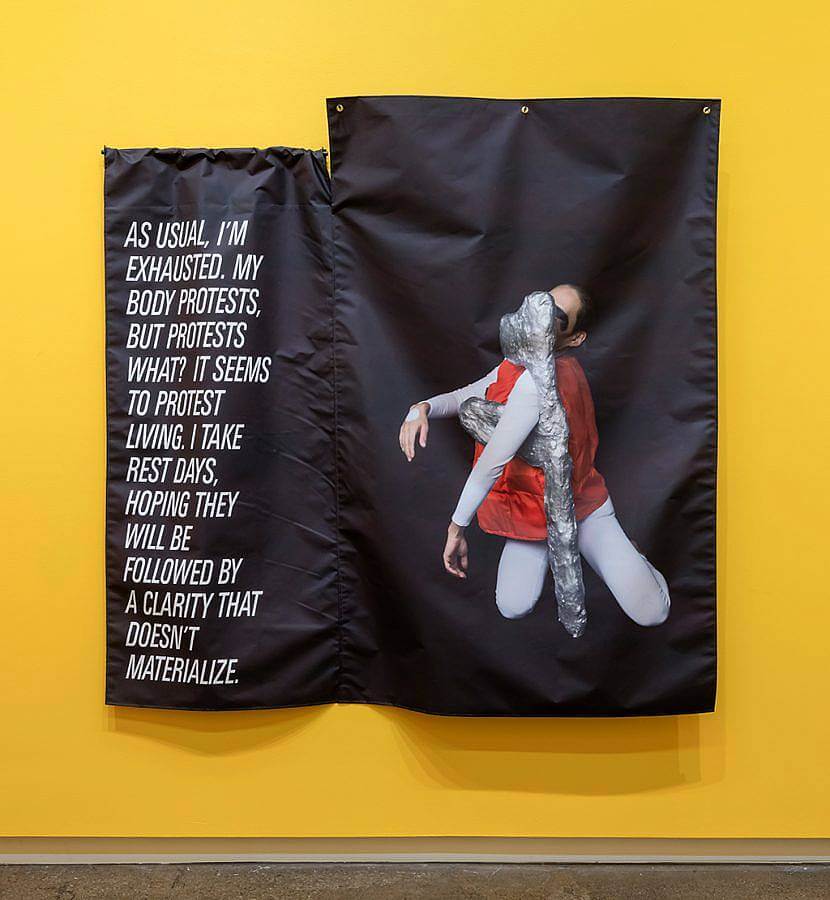

We are Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau, a multidisciplinary artistic duo from Montréal. We usually call ourselves installation artists but more and more, performance is at the centre of our work. That sometimes manifests as a live performance in the gallery or theatre, but more often as performance videos, photos, and sculptural assemblages that contain props, or even as printed scores. We’ve been collaborating for the past 20 years and have a long background in DIY music and poster art that really frames and shapes how we approach our current practice. We don’t call ourselves performance artists because at this point our performance-based work has been us working with professional dancers or opera singers to interpret our works instead of performing ourselves. That said, amidst the challenges of the pandemic, we have started working on a video series that we will perform.

How did your interest in art and performance begin?

Chloe: For me, it’s something I was always really interested in, but growing up in a pretty working-class family, it didn’t really seem like something meant for me to pursue as anything more than a hobby until I was in my early 20’s, even though I had started getting really involved in DIY music and artist-run culture as a teen. I spent my formative years living in Ottawa where at the time The National Gallery was free to attend, so I’d get brought there on school trips. I also started going fairly often as a young teen to kill time after school and before punk shows. It was fairly close to two of the places that had a lot of all-ages shows in the early 90’s and to the café all the teen punks and goths would lurk at, to the dismay of the staff. I didn’t know anything about contemporary art yet but became really obsessed with General Idea’s One Year of AZT.

Can you talk a bit about your collaborative relationship as a duo, and more broadly on the role of collaboration in your projects?

Yannick: Our formative experience with collaboration has been through bands. Before we met we both played music while starting up as visual artists. The process of exchanging ideas and proposing structures on which others can add on to conceptually is a really rewarding one. It is not so much about collective authorship but rather about shared labour. This is especially evident in music since every contributor’s task is usually defined by the instrument they play. It’s a bit fuzzier operating like this in visual art since our aptitudes overlap so much. It definitely makes the process of creation to be never boring. Indeed, we both feel it gets much harder to keep our stamina when we have to work on our own on a segment of a project, while the other has to be away for a reason or another.

In your operatic performances, the human voice is what carries the narrative. What role does song take in your practice & and can you talk about the process of writing music for your work?

Y: We always saw strong similarities between our songwriting and our visual work. Before we started integrating songwriting into our performance work, we wanted to keep both practices wholly separated. We felt only recently that we were ready to integrate song in our performances, as our transition from sculptural installation to performance brought us to invest ourselves much more into narrative. But before, let’s say around 2007-2012 when the band was still around, and we were in the midst of developing our massive, immersive, all over screen-printed paper installation works, we saw a strong relationship between how we treated colour, how we were covering the surfaces of the gallery and the haptic quality of the material acted a bit like how sounds— really loud sounds in the case of our last band— envelop us physically, and move us places. There was also this time-based quality to our installations, where the paths and obstacles we created with the paper objects and surfaces laid around the gallery space to create this developing narrative in time, involving the body in motion, and experienced through vision and touch.

The fun thing is, now that we moved on from being music performers, we are not limited by our own musicianships, and through the input of the performers who collaborate on our pieces, there is almost no limit to how the music can be shaped. It’s also interesting to observe how the personality of our performers can affect their approach to our music; we have written graphic scores that can be read in many different ways, giving wildly different results, which is all super interesting to us.

All of your pieces play upon the inherent theatricality and agency of objects. In a broad sense, how do you feel your work explores this theatricality?

Y: We’re really into the idea of exploring the concept of compassion through our relations with objects. Initially, we were interested in this idea of “getting to know” objects better through their apparent misbehavior. Actions/reactions of objects beyond their programmed usefulness–failure, decay, and so on–are all negatively coded terms that really just show our capitalist/productive bias towards them. We started integrating chance and compulsivity in the composition of our installations, more and more the planning happened directly in the gallery. Objects were setup in manners that would provoke some kind of material change with time, things, crushing, flattening, bending, peeling, and so on. This kind of “misbehaviour” from the things we were making looked more and more like a sort of expressive essence coming from them, and not all those coded negative things. From there it was easy to see how those same notions could be applied to our reading of the human body.

Your performance work, Becoming Unreal, alternates between spoken and sung sounds to offer a perception of the natural world, “beyond the human story,” in addition to the human impact on a natural world we’re supposed to be a part of. What is the inspiration behind the environmental piece?

C: Becoming Unreal was a response to our friend Jasmine Reimer’s installation work Of, In or Under (2018). I had met Jasmine at a writing residency in Winnipeg in the summer of 2017, which, incidentally was where I wrote the first draft of the script for Becoming Unreal. We became friendly and she ended up asking us and Patrick Cruz to each do a performance in response to her piece which, amount many other elements, had hundreds of mall objects cast or encased in green rubber. Lots of these items were stones, seed pods, and snails so it automatically brought ideas around ecology, but also the ecology of a material-based art practice, which is probably something I’ve had conversations with all my peers working in sculpture and installation. There is always an ambivalent tension of making things now, and yet I love things. Right before I wrote the lyrics, we had been attending 8 Days, which is a roaming residency for Canadian choreographers, and that year it was in Woody Point Newfoundland, which is a small fishing village inside Gros Morne National Park and I was shocked at how little animal life we’d see on the beach compared to what I remembered of my childhood living in Atlantic Canada. We planned for the piece to be performed by our colleague Xuan Ye who has a really deadpan delivery and have plans to produce a video of the piece which has had an entire second life after presenting it in Jasmine’s installation. It’s actually been the catalyst for an entire series of fairly minimalist performance videos, each featuring a solo performer and vocal score.

Can you discuss your work and performance, “An Autobiography of Air”?

C: “Autobiography” was commissioned by the Musee d’art Contemporain de Montréal and the title and some of the main narrative threads were influenced by attending an academic conference, of all things. I had gone to see Mel Y. Chen speak at McGill because I had read their book Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect while working on my MFA and found it super interesting. Anyway, they spoke a lot about art that used air as a subject matter and medium, while also talking about the wildfires going on in California and being stuck at home with a head injury. I was going through a pretty intense chronic-illness flare-up at the time and some of Chen’s comments got me thinking about the material potential of sound and especially of spoken or sung text that could echo in space. It was stuff we had thought about a lot in our days in noise rock bands, but never about the potential of sound-as-material when one is stuck in bed, unable to make it to the studio.

Because the curator we where working with, Marie-Ève Béaupre wanted there to be multiple performances during the length of our exhibition, we conceived of doing the piece as a recombinant narrative in which we’d work with 4 performers, two singers (Sarah Albu and Maya Kuroki) and 2 dancers (Lara Oundjian and Ellen Slatkin) where each would have their own vocal and movement score but they would be in different pairings, each pairing created a different performance with totally different dynamics. Because the score involved moving the elements of the installations around, it meant they had to start and end in different parts of the gallery each time, and the installation was always rearranged so the objects could be said to have been performing as well. We wanted to have the installation and the live-work create this symbiosis wherein each would be different if folks came back for multiple viewings.

Do you have any upcoming projects or shows?

C: We are having a solo show at Idea Exchange in Cambridge, Ontario that runs late November through late February, there will be a few online talks and the like. Currently, we are working on a new series of performance videos, the working title of the first one is The Line Between Human and Not and it will be showing at The Owens Gallery at Mount Alison University in Sackville, New Brunswick both onsite and online this winter. As the series comes together, we’ll be trying to get it to tour. It feels really strange to be working on exhibitions and new videos during a pandemic but we are trying different things and figuring out how to be nimble.

What is your current studio/workspace like?

Y: We have a 1000 square feet space in the Ahuntsic district in Montreal, in an area called the “Fashion District”, named that way because of the multiple purpose-built factory buildings that got erected there in the ‘60s and ‘70s to retain the garment industry in town. This only partially worked out in the long term, but the empty spaces are getting rented to artists who are fleeing the ever-increasing rents from more central areas of the city which are all gentrifying exceedingly fast.

It is a multipurpose studio, where most of our working surfaces are foldable or on wheels to adapt to different types of production: sewing, sculpture, painting, or like we were doing until last week–exhibition prep, where we were documenting the hanging process for an entire exhibition for it to be installed at distance because of the sanitary travel restrictions from the pandemic. About two-fifths of the space is storage, archive, and tools— quick access to our older work is necessary since we are really into re-purposing, re-staging objects in new roles. We are about to get on the production of a new series of video works in which we will perform ourselves, a first since our touring band days. We have been workshopping and taking online classes on acting, miming, and mask theatre in order to get prepared for this new project. We realized as soon as the pandemic hit that to get some of our new performance work done we had to work independently from our usual group of collaborators for a while. We are still in the development stages, but the flexibility of the studio space allows us to set up a minimal film set there.