Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

My name is Billie Carter. I was named after my father, who was named after his father, who was named after his father. I believe things like that are important to note. We’re all part of a lineage; we are the culmination of the people that come before us. I create based on these beliefs.

How did your interest in art begin?

This is a complex question for me because most of the artists I’ve met have known that art was their calling from an early age, and had teachers and parents who saw their talent and invested in them. That is the total opposite of my story. I literally just fell into it.

Coming into undergrad, I had no idea what I wanted to do–I switched my major three times in one semester freshman year. I just kept gravitating towards things I liked, which initially landed me in media/radio. Then I gravitated towards filmmaking, which led to image-making. That felt closer to what I wanted but still felt unfulfilled.

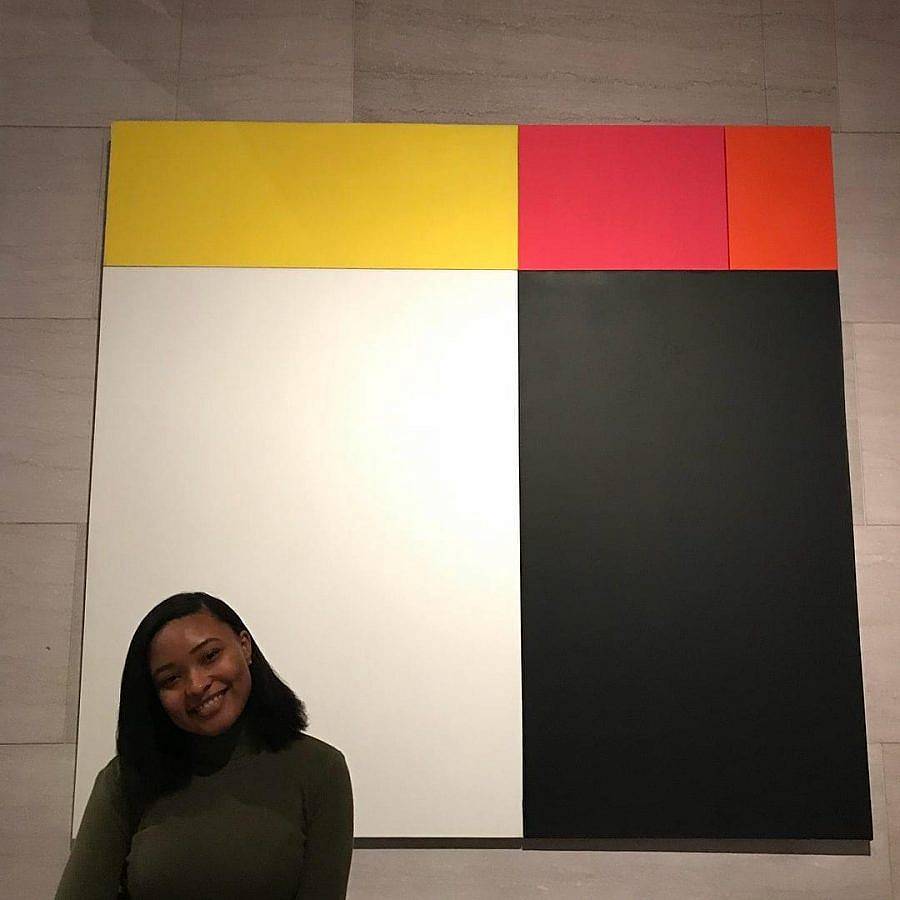

In the first semester of my senior year, I studied abroad in London. I went in with a very basic understanding of photography. I ended up taking courses under Chino Otsuka, who introduced me to conceptual artmaking and experimentation with photographic materials. It was the first time I felt fulfilled with the work I was doing. I ended up making work that led me to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago the following year.

The way you display your work, the repeated parts of your process, and the images you choose seem ceremonial. Do you see your pieces as commemorations?

In a way. I’m interested in what influences a person to view something as being “commemorative” rather than creating something commemorative in and of itself. The process of how someone makes sense of a thing and classifies it, while another person views that same thing and classifies it as something completely different. That’s one of the bigger picture questions I think about. What is the objective truth? Is there such a thing? How does “truth” influence our memories? I’m still trying to make sense of it.

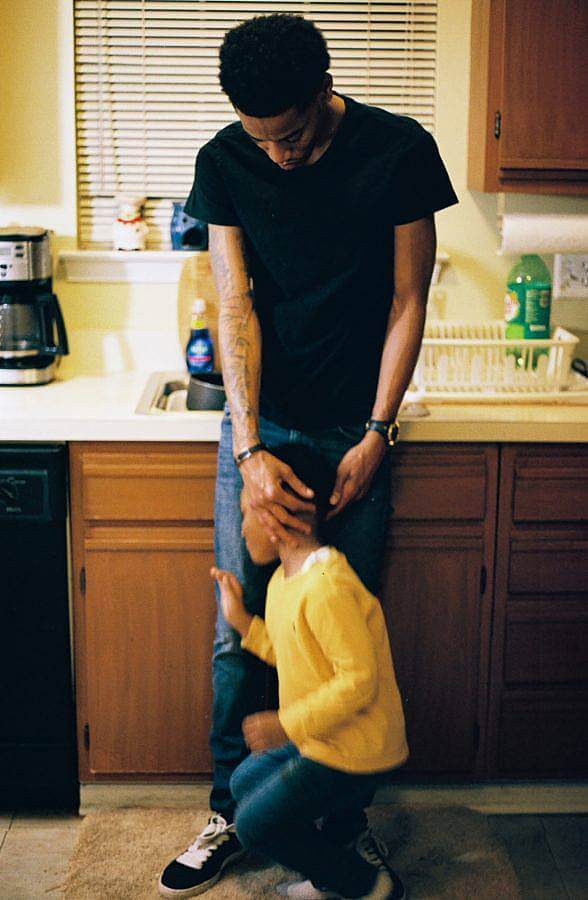

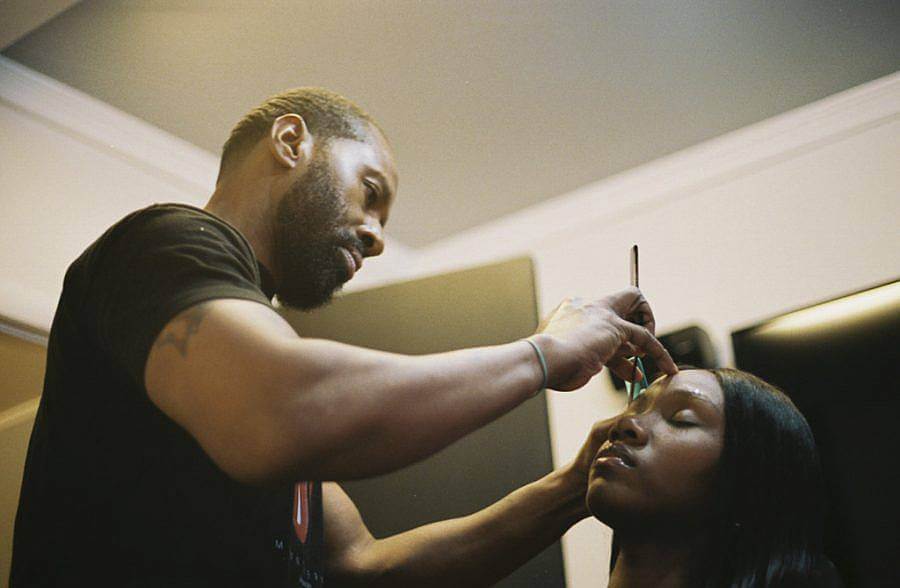

In your earlier series, “Black Fatherhood,” which was featured in STACK Magazines, you portrayed three fathers of different ages. What was your process for capturing the intimacy between them and their families?

I wanted to meet the families in their elements, and adjust to what worked for them. I didn’t want to come in and create a narrative, but rather capture what was already there. I was a guest in their homes and I wanted to maintain that respect. The youngest father I met on a film set a few years before, I emailed him and he was more than glad to be part of the series. The other fathers were friends of my older cousin. They all gave me locations to meet them, and from there I asked questions, got to know them better, and as we became more comfortable with one another I began taking pictures of what they would already be doing even if I wasn’t there.

With the youngest father, his son had a lot of energy. I captured the moments when the father tried to calm the son down to stay still for a picture, along with a few images of his son moving around. The middle-aged father was a barber. His daughters met us there and I captured their conversations. The youngest daughter wanted her eyebrows arched, and her father did them for her – which ended up being one of my favorite images from the series. I met the oldest father and his family at a local restaurant that displayed his art. I made sure to get images of his art in the background as he and his family were talking. Because the family was so huge, we decided to do a family portrait in front of the restaurant. I took pictures of the family trying to get everyone ready for the picture, which resulted in really precious, intimate moments.

Can you introduce us to your most recent project, “Congratulations Michael (In Progress)”?

I want to take an excerpt from my artist statement:

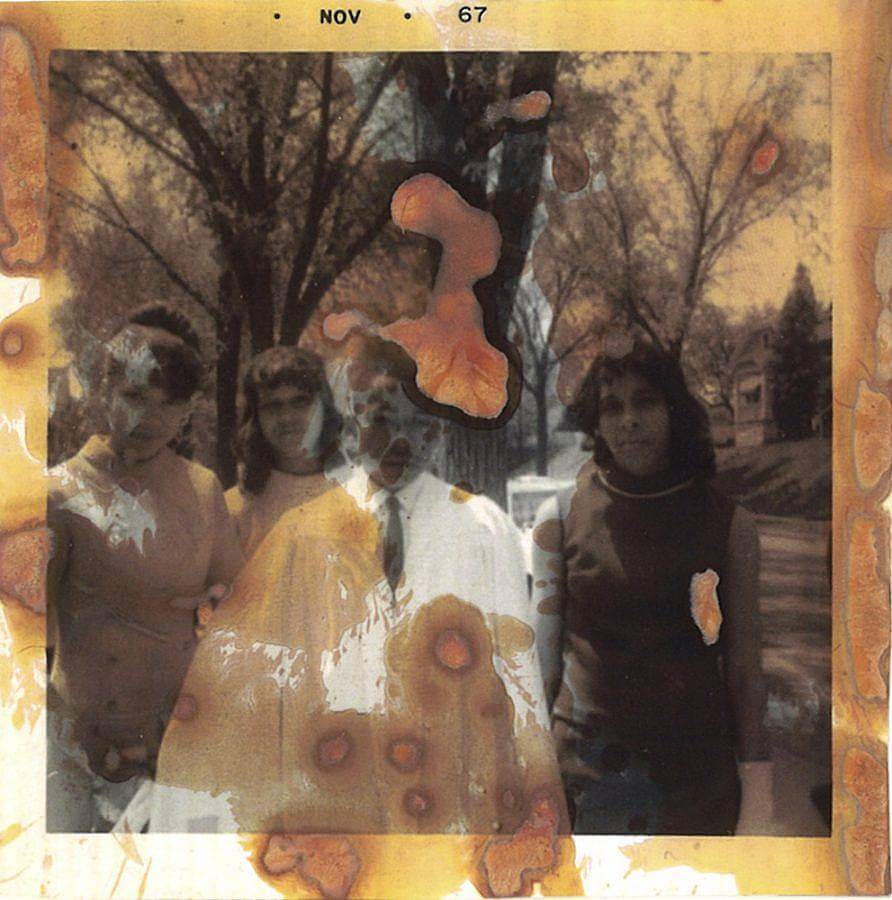

“The process of remembering is a universal experience. Every day we have rituals and habits that we need to recall to function in everyday life; how to walk, how to speak, how to write, and so on. Over the course of time, old routines evolve into new iterations. The process of remembering and its evolution continues to shift throughout our lifetimes.

This evolution of memory became complex for my grandparents when they were both diagnosed with dementia. We would look through old photo albums but they couldn’t identify who were in the images, or recall the depicted events. Our family photographs, originally meant to function as a site of memory, transformed into sites of forgetting.”

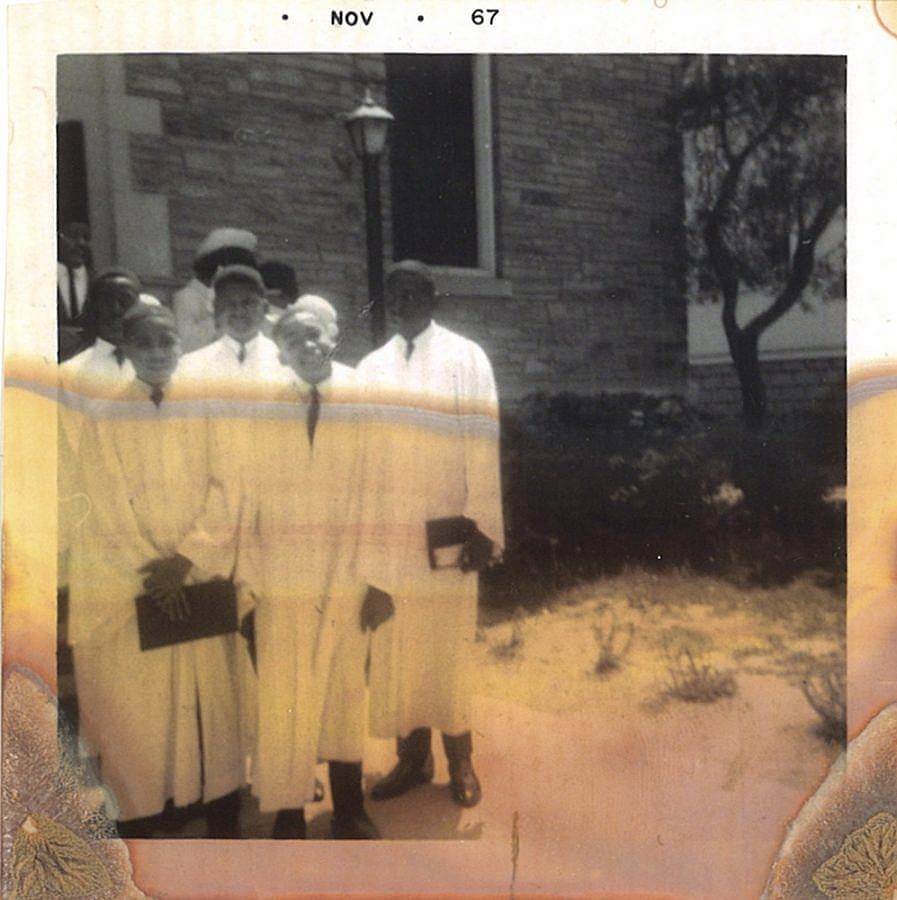

Most of my work is rooted in observation, which leads to me trying to process the experiences through writing. As I wrote about watching my grandparents, I kept dwelling on words such as “fade” and “deteriorate” – which I investigated through photographic materials and processes. I reprinted photos of my uncle’s confirmation, a significant cultural rite for my family, and painted over them with Kodak selenium toner, a chemical originally used to preserve images, to slowly deteriorate the images over time.

What is your current workspace like?

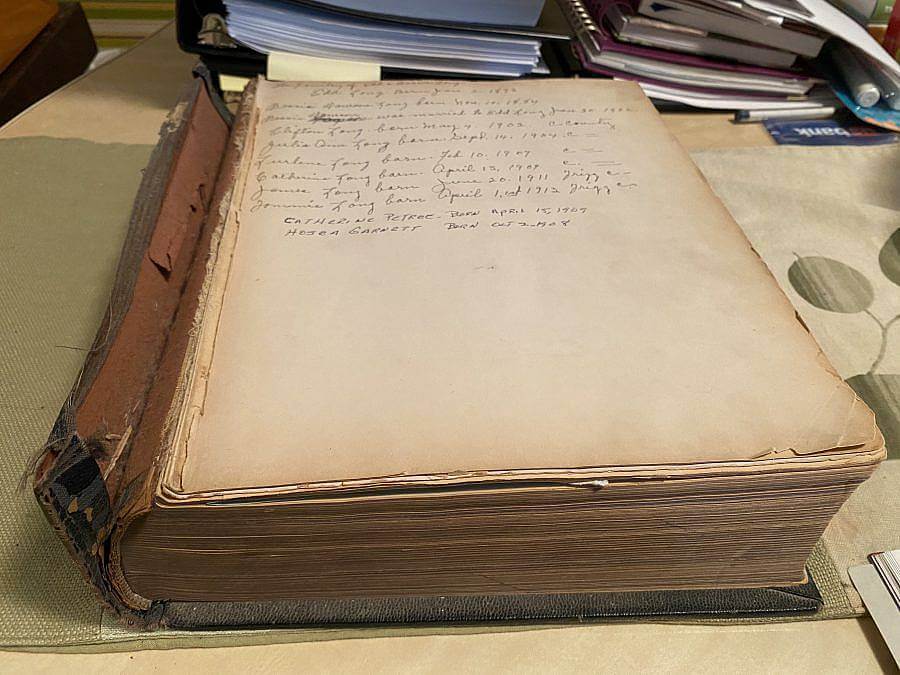

I turned our old dining room into a somewhat studio space. I’m in between a 40-year-old china cabinet and a 20-year-old dining table. In front of me is my grandmother’s family bible – which includes the birthdays, marriages, and death dates of everyone on my grandmother’s side of the family – which begins with her grandparents. The farthest we can trace that side of our family is to Louisiana in the early 1900s. I’m also surrounded by some of the art my grandparents have collected over the years. Across from me is old wood paneling we had to pull from the wall upstairs. We’re the second family to live in this house which has been in our family since 1950. I’m saving a few parts of the wood paneling for a potential future project.

Many of your pieces evaluate how emotional attachments obscure and construct memories. How has exploring different depictions of obfuscation– translating your own words into a different language, plexiglass, white paint, corrosive materials, etc–allowed you to play with subjectivity and temporality around remembering?

I think about the different ways objects hold memory. With each of these materials, I considered their original context to my personal experiences. As a child, I developed a romanticized idea of family and how the family “should” be or “should” act. This idea slowly fell apart through the years. I related this to the objects I manipulate in my practice. We buy certain items because we expect them to function in a certain way. But what happens when they don’t function the way we anticipate? How do we value these objects? I started thinking of family in this way, specifically in relation to my experiences with my father, who passed early last year.

When participating in the Setouchi Triennale last year in Japan, I displayed my work in a traditional family home, using functional, everyday materials such as washi paper and plexiglass, to create a piece about the complexities and dysfunctions of our relationship.

For most of my life, I’ve written about major experiences and observations to process what I was feeling. In my practice, I make physical those experiences I’ve written about. Observing and watching my grandmother navigate the act of remembering pictures she and my grandfather took led me to think about the function of a photograph, in which one of its primary functions is to remember. What would happen if the photograph instead reflected the process of forgetting? This led to experimenting with my grandmother’s photos.

In one of your thesis works, you created what looks like a reel of your grandmother’s memory. Is this intentional and what was your intention in layering those fragmented images, which appear to be at different rates of decay?

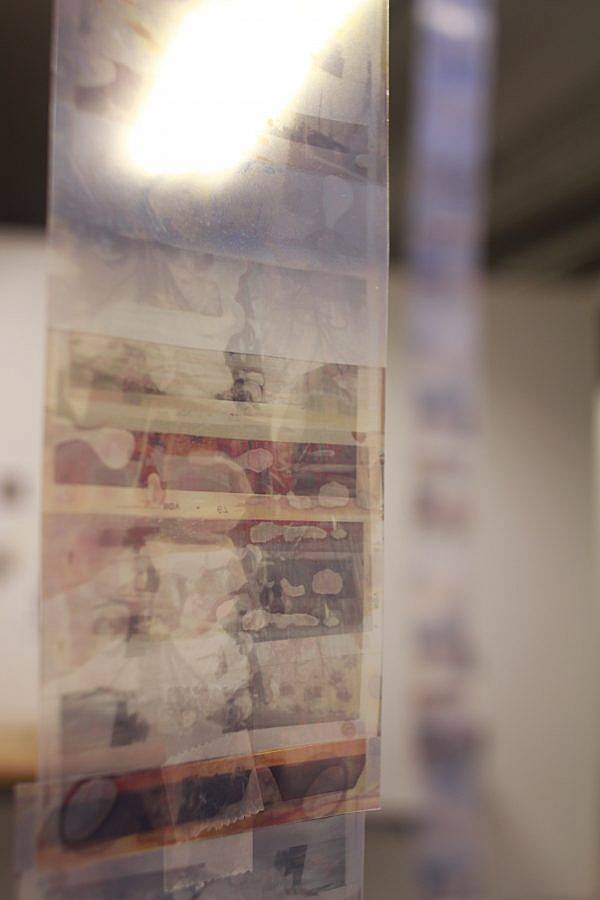

The inspiration came from later interviews I recorded with my grandmother as we looked through her photo albums. I noticed that she would keep repeating the same details about an event until she could remember more. The details she remembered first were easy for her to recall, but other details wouldn’t come to mind until much later, and some not at all. I started writing about these experiences – even if we save memories through images, what will our minds choose to keep or discard? Do we really have control over what we remember?

I wanted to recreate a material version of this experience. I scanned the deteriorating toned images, layered them on top of one another in photoshop to create small strips, and printed them on transparent paper. I continued experimenting with the materiality of the paper and created longer transparent strips with repeated images and different ranges of deterioration that hung from the ceiling and piled on the floor. The events depicted in the photographs are abstracted by the transparent paper enough so viewers can see vague, repetitive details but cannot piece together a coherent narrative – referencing my grandmother’s process of repeating phrases to ground her failing memory.

Can you talk a bit about the work’s you displayed at Circle Contemporary, for Box Box Box Sun Sun Sun with Arts Life and us here at LVL3?

Because of quarantine, I wasn’t able to finish my thesis the way I planned and didn’t have access to the same equipment and studio space. This led me to scale back and think about what drew me to manipulate these images in this way in the first place. I wanted to focus on the materiality of the images, which is where the heavy metaphors for the work are placed. I decided to frame the images in a simple wood frame so that from first glance the images look like standard framed photographs in a home, but when you get closer you see the photos slowly falling apart. The embroidered piece is from a cousin of mine. She wrote the note for my grandmother who my work is centered around. It has hung in our family home ever since. The contrast between someone else’s memory of my grandmother vs the metaphor of her own memory was an interesting combination to me, which is what led me to include the note.

Do you have any current shows?

I’ll be showing a few prints from the Congratulations Michael series in the Launch exhibition at SAIC Galleries at 33 E. Washington St. The show will run from October 19th – November 24th, 11 am-6 pm by appointment.

Interview composed by Amanda Roach.

Alt-Text by Ruby Jeune Tresch.