How did you get started as an artist?

Growing up in rural Mississippi, I wasn’t exposed to a lot of art. But I was the go-to person throughout middle school and high school for designing t-shirts or drawing the covers of yearbooks. I found my way to the San Francisco Art Institute (RIP), and really had my mind blown by what they called “new genres:” video, performance, wierdo stuff that didn’t fit in. Even then I was a bit traditional in my commitment to crafted objects, but the fearless attitude of “new genres” bled into my work as much as it could.

After undergrad I lived a few years in Houston, TX, where there is this amazing and supportive art scene. I kind of had this secret art career in Texas. I was making these very pleasant animal forms that had a bit of edge in their materials and craft, but perhaps weren’t the most significant things I’ve ever made. Still, I was able to exhibit at places like Barry Whistler Gallery in Dallas, Commerce Street Arts Warehouse in Houston, and the Galveston Arts Center. Eventually my work got stuck and I moved onto graduate school at Yale University School of Art. Looking back at my old work now, it still blows my mind that I got into school. One thing about Yale Sculpture is that they are in a position to take a few risks on who they accept—I’d like to believe it paid off for me- my work got more real and less prescribed, and a lot more confusing in good ways. At any rate, my wife Kelli Connell and I moved to Chicago after she got a job in the photography department at Columbia College Chicago, and I’m happy to call it home.

Can you talk about a term you’ve used to describe your work, Butchcraft?

Butchcraft is doing everything in the butchest way possible. Buy it premade or make it on the lathe? Make it on the lathe. Hand-punch holes or use a drill? Hand punch ’em. Paint it or airbrush it? Airbrush it. Butchness is such an excessive form of camp, with its swagger and style. The ways I make sculpture mirrors this exaggeration of effort and inflated sense of butch pride.

What is your studio or workspace like?

My studio is one-part grandpa’s basement, one-part hoarder’s hutch, and one-part man cave. If you’re someone who needs things to feel in order, my studio will give you a heart attack. As is the butch way, I have accumulated lots of hand tools and bizarre materials over the years and a point of pride for me is in having what I need on hand, which isn’t always easy as I only have about a 300 square foot space.

My process is messier than it needs to be- I don’t like picking up after myself until a project is done in case I need to “go back,” and I get great satisfaction in seeing the tide of messes and tools swell up in my studio as a piece gets closer to completion. In these recent months of sculptural sketching, my studio situation is quite a sight- I’ve started working on lower surfaces than usual and trying multiple things at once: no one coming in would have any idea of what’s going on in there.

How important is humor to your work?

Humor is disarming, makes it a little easier for the viewer to open up, even makes some of the icky stuff about my work acceptable. There is something funny about the sorts of objects we desire, and about the ways queer identification is performative. I like to add little jokes and jabs as a way to wink at the obtuseness of a lot of my pieces, which almost, but don’t quite make sense. Also, lately I have been trying to crack myself up in the studio just to make myself feel better. I do often start with assemblage when getting into a new body of work, which lends itself to humor- my favorite recent piece is a bundle of glass grapes completed by a bunch of yellow smiley face stress balls. It’s visually logical and all the signifiers are trying (albeit not very hard) to make us feel better. But obviously, the piece is also a brain freeze when you try to make actual sense of it.

You take materials like cork, foam, soap, and wood and fold them into objects and bodily forms they might not typically be used for. Can you talk about your approach towards extending and playing with materiality?

Materials have meaning. I use a lot of reductive processes to unearth some of this meaning- digging out the associations we have with textures, surfaces, gravity. The results give the dual experience of experiencing the material and participating in its transformation. I’m attracted to materials like cork, graphite, or wax. These have a density, an opacity, and a bluntness to them that I think suggests connection to the body.

Speaking about materiality and technique, how do you interpret craft in your practice?

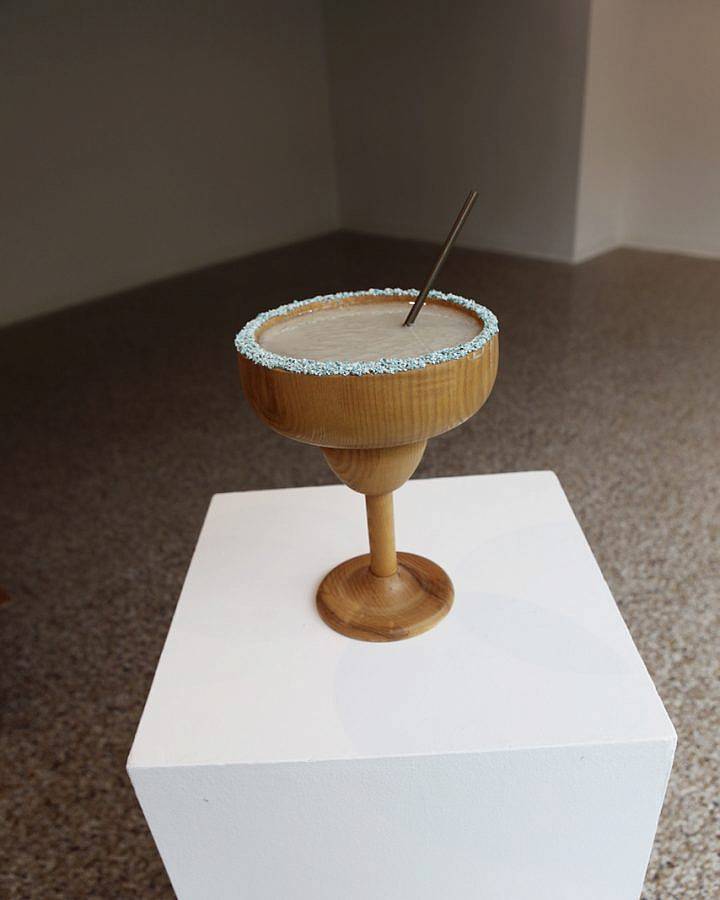

Everything I make is meant to feel heavily crafted. When you push craft past a certain point, it goes from feeling skillful to feeling out of control- I like that such control can turn into chaos on its own. We relate to objects in really specific ways, often as consumers, and often subconsciously. Extreme craft gives viewers the chance to have that “shopping” experience (I like this wooden margarita glass, or I don’t like those life vests), but the accessibility of how things are made allow us to consider why it is that we desire the objects we do. I’m most interested in the desire itself, and try to make objects that embody a sort of androgynous desire.

What physical and conceptual qualities do materials like Western tooled leather bring to a piece?

Growing up in Mississippi (a thread that runs beneath most of my work), and I was often exposed to tooled leather. It was fascinating to me that such a masculine craft and aesthetic was so delicate and feminine at the same time. Such an unexpected place for me to start identifying less binary gender presentations.

In my work, leather tooling is a craft I borrow as respectfully as possible. Leather is skin, it is protection, it is garment, it is gear, it is sex. But when you tool it, you get beneath its surface, using a hammer and a variety of tools to pull meaning from beneath the skin. By using this literally heavy-handed way of making meaning I’m trying to reveal the discord in the masculinity of the material. Like in the traditional craft I usually tool floral patterns, but my tooling is a bit more suggestive and a little less unified that what you’d find on a wallet or saddle. This and its connection to drawing pull leather tooling into an interesting space of artist references.

Do you ever wear your sculptures?

So much of what I make relates back to the body, specifically to the desires of an androgynous body. I am constantly using my own body to model my sculptures, trying them on to see if they really work, which is weird since that is totally unnecessary to the presentation of the work. I don’t know if you can tell from looking at the work, but I do spend a lot of time physically in it, both as a way to see it, and as a selfish opportunity to connect to charge of the sculptures. For instance, if I’m working on a glove, I’ll often wear it and pound it as I look at other works.

So, softball?

Softball is a recurring muse for me. Personally, I’m quite bad at it and grew up envious of the girls who could play, not only for their prowess and talent, but also for the freedom in the invisibility of women’s sports. The magical thing about women’s athletics is that no one is watching, so little suggestions of defying the patriarchy seem to naturally seep through. I once saw a rugby player take her mouthguard out and put it in the sweaty, grass stained sock she was wearing. Or that time the Canadian women’s hockey team smoked cigars on their Olympic victory ice. Even the women on softball teams I have played (badly) on developed their own systems of codes, signifiers, and sorts of languages. I’ve made several sculptures that reflect this imagined utopia of a women’s sports bubble. Part of me hopes that in exploring the content of softball I will somehow gain access to the subculture. The fact that softball has such lesbian connotations is exciting too, as the role of lesbians in feminism has been so complicated for the last 50 years. It seems to push back against queer participation has really diminished in the last decade, although I did recently hear the epitaph “no bow, lesbo” to describe why some softball players wear exaggerated hair bows on top of their extremely tight ponytails.

What are you working on right now?

I spent the first half of 2020 finishing a commission by the Cleve Carney Museum of Art to recreate three orthotic corsets worn by Frida Kahlo. I was grateful to have something prescribed to work on at the start of the pandemic. The process of making the corsets was intense and I learned an extraordinary amount as I was basically working off of pictures from the internet and experimenting to see how the original makers did it. It was making as archaeology–very different from my usual process where making is sort of a catalyst for more abstract ideas of craft and identity.

Now that that project is complete I am in an extremely weird spot. I went a little deep as a craftsperson, and now I’m going back and forth between humorous works like a giant polymer clay hacky sack or shrouded crystal figurines to just plain bizarre leather and fabric works. The corset project took a surprising amount out of me creatively, so I suppose I’m just experimenting a lot now and struggling with the worst thing about being in an in-between space: when you’re working on sketches, why bother finishing them? Still, I’m plugging away on some of the weirdest things I’ve ever conceived.

Interview composed and edited by Maddy Olson, Joan Roach, and Ruby Jeune Tresch