Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

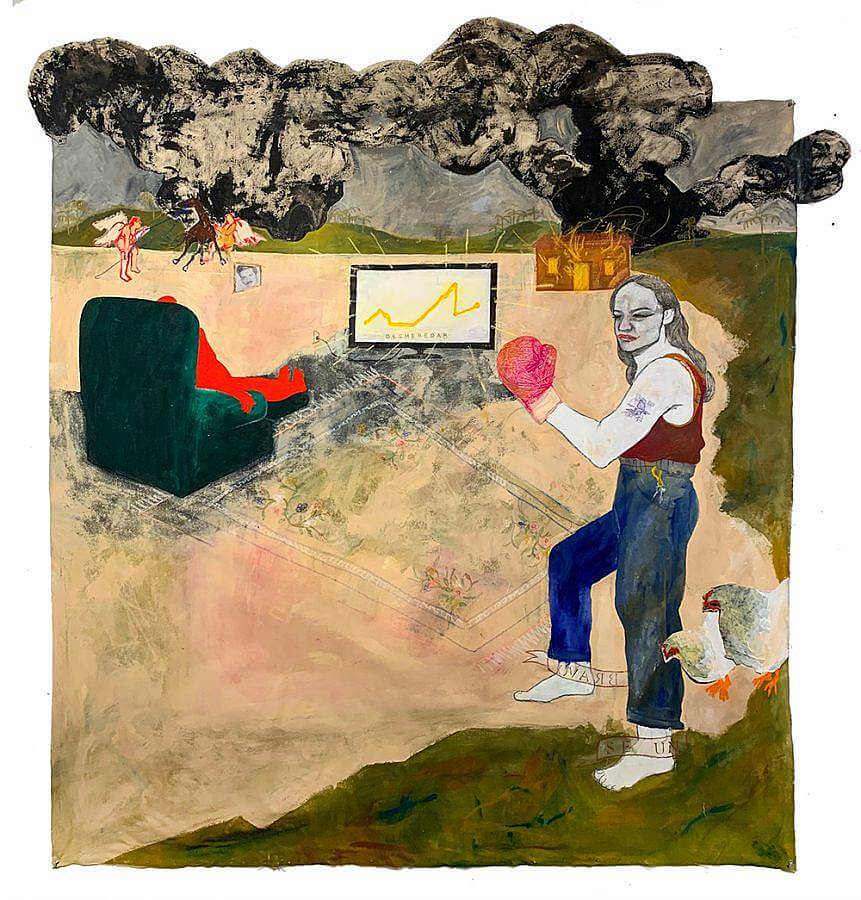

I’m from New Jersey, both my parents were born in New York (Brooklyn and Washington Heights), and my grandparents come from Cuba and Italy. I had an intensely Italian upbringing and was barely immersed in Cuban culture, hence the fascination with it now. I identify as a queer person. I consider myself a mixed-media artist, but most people just call me a painter because it’s easier and it’s what I do most often. I paint, I draw, I sculpt, I write, and sometimes I make video work and wearable pieces.

How would you describe your building and material process in relation to collage? What advantages does collage offer you when telling a story?

Collage just feels so much more instinctive than anything else. It’s sort of the basis of my entire practice. I have a collaged sense of identity, and so the work reflects that. I need to be surrounded by exciting and strange materials to really work. My mother is an art teacher for young kids, and she’s always getting bulk donations of craft items and trinkets. I tend to raid the collection a lot. I like knowing that the materials have a history to them, it gives me an idea of what function they’ll serve in the work. Some of my sculptural materials are items that have lived in my childhood home as long as I did, which is important to me as someone whose work is very much about the ancestral home.

Can you speak about your use of cut and unstretched canvas?

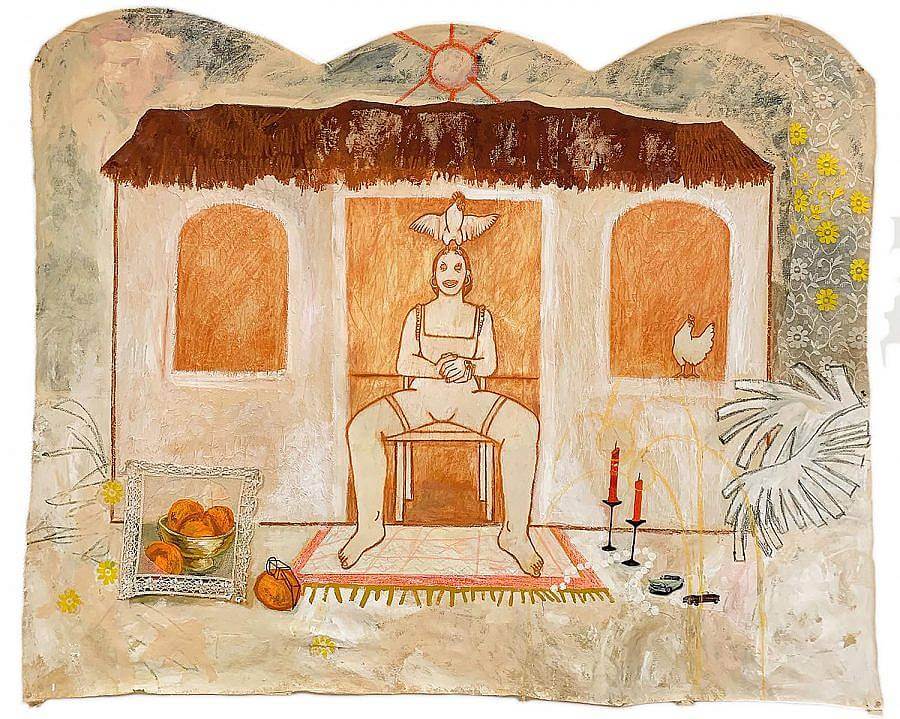

The unstretched canvas was somewhat inspired by a friend who also worked that way, her work was rooted in lots of embroideries, and the unstretched canvas was important for that. It’s also just a general aversion to a hard edge, which suggests a container, and suggests that the image ends where the stretcher bar hits. The unstretched edge is much more giving, and fluid, less authoritative. I needed the work to be unstretched so that it could be intuitive. If the work had to get bigger, I needed to be able to glue another piece of canvas to make it bigger. It’s much harder when a stretcher gets in the way. I needed the work to be flush to the hard surface of the wall, as I like to draw on the canvas with graphite, wax pastel, and pen, and a stretched canvas doesn’t receive the pressure needed for drawing in the same way. And of course, I have a love of tapestries, they feel more inviting to me, less like a painting, and more like a mural. Funnily enough, I have been working stretched lately, mostly because I’m veering into sculptural painting and need the support system of the stretcher. I’ll always come back to unstretched though.

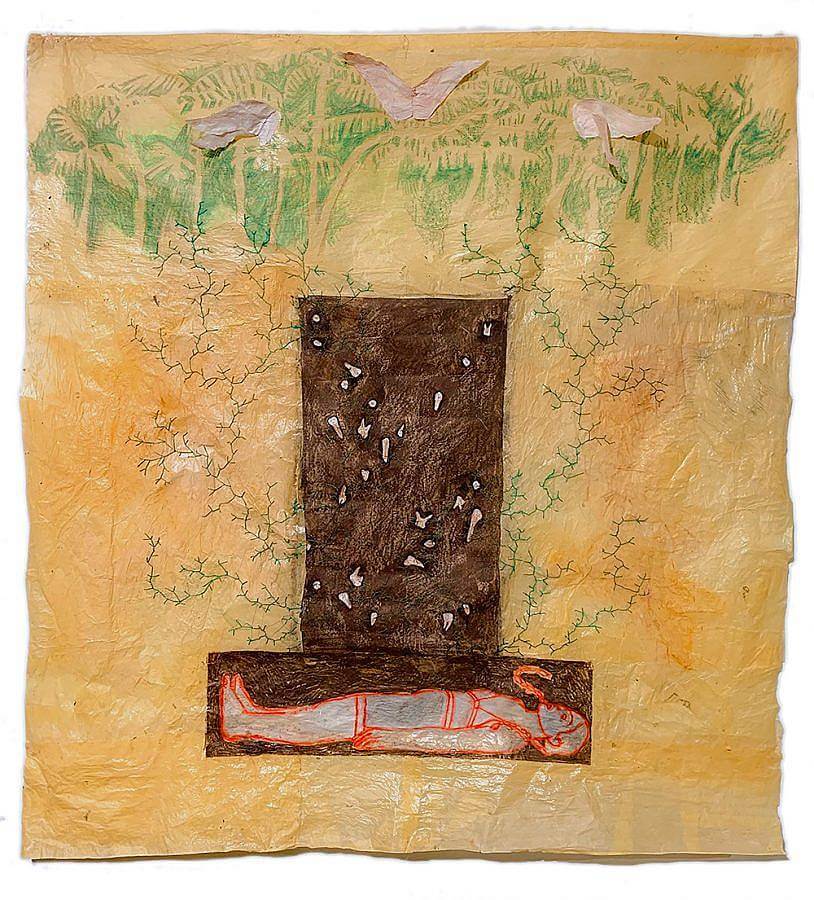

Your works draw associations to traditional Catholic iconography and compositions, can you talk about this influence on your practice?

Both sets of grandparents were very much Roman Catholic when I was growing up. My Abuela used to take my dad and aunt to a church in Washington Heights that had the preserved body of a dead nun in a glass casket in it when they were kids, it was that intense. My parents tried to get us in church a little, but we all really weren’t committed to it. We were just classically bad Christians. The imagery was lasting though, I mean, it was just so melodramatic. I also have very strong visual memories from my Cuban grandparents’ funerals, which took place at this gaudy church in NJ, huge archways, gilded candlesticks, the works. Most of the service was in Spanish, which was embarrassing for me and my brothers, who couldn’t follow along. There was also embarrassment for me and one of my brothers because we were both closeted at the time. It was traumatic then, but now I find a lot of humor and kitsch in it.

Do the landscapes you create in your paintings, exist?

They both do and don’t. I consider them Heterotopias, a variation of the utopia proposed by Foucault, which operates as a site that does not exist but is rooted in notions of sites that do exist. So the setting is not a real place, but it is a heterotopic version of the Cuban countryside, which I haven’t yet experienced physically. Once I get my feet on the ground there, I’m sure the work will change, to an extent.

The persons and figures in your paintings have distinct emotive facial expressions. How would you describe your approach to conveying emotion through their gaze?

The face usually comes first, before anything else. I was always doing silly portraits as a kid of whichever actress or musician I was obsessed with at the time. I think it just comes from a fascination with internal worlds, which can really be seen in facial expressions. I sometimes look at photo references, but not to copy, mostly just to find the person with the right mood, so I can bring that mood to my figure. It’s also important for some of the figures to have blacked-out eyes, as a sign that they aren’t or have never been really alive. I’m often creating figures that are an imagined family, so the resemblance is usually important.

How do you use your practice to navigate and interpret your Cuban – American identity?

My work is an ongoing conversation with myself, and my ancestors. The few stories I’ve heard from my father have become doorways into painting. I consider the paintings a sort of sounding board for insecurities I have about my lack of a strong Cuban upbringing, and a place for me to hash out my complicated feelings toward my late grandparents. Cuban/American politics are, of course, charged. I don’t hold similar beliefs to most Cuban Americans, who largely veer conservative and anti-socialist. This is an alienating thing, as someone trying to understand my culture without being able to visit Cuba yet. I have felt excluded from Cuban American culture, and I am physically excluded from the culture of the island. This is made even harder by the fact that the island itself is so, so close. My grandparents came to New York from a small town in central Cuba called Fomento during the Batista regime in the early 40’s, before Fidel Castro had even begun making waves. They were not very prosperous, they came from large farming families with many siblings to help work the land. My Abuelo was something of a Cuban cowboy, which is endlessly fascinating to me. Though they didn’t flee communism (though you could argue that Cuba has never really been truly communist), they watched the revolution from America, and became susceptible to American propaganda about the Cuban Revolution. The paintings help me collect their stories, reckon with their beliefs, and investigate questions that can no longer be answered now that they’ve passed. The painting also helps me parse my own opinions on Cuban/American relations, particularly in relation to the U.S.’s suffocating embargo, and Cuba’s challenging history with its LGBTQ community.

Can you tell us about your 2020 work, “Bohio after Midnight”?

This work comes directly from a story told to me by my father about my great grandfather, Pedro Peña, who owned a little marketplace in their hometown of Fomento. It was basically like a convenience store. At night, the store would be turned into a dance club. I’ve been obsessed with this story ever since hearing it, the idea of something mundane coming alive at night, and also the inherent queerness of a DIY dance hall, which is of course exciting to me. The unstretched canvas surrounding the stretched suggests day, while the stretched holds the excitement of night, and the circular frame in the center features a picture of Pedro Peña himself, the only picture I have of him, holding potatoes from the garden when he lived in Virginia. Once a farmer, always a farmer.

What artists have influenced your practice?

Of course Ana Mendieta, how could she not? And Belkis Ayon, who is not loved enough. Kerry James Marshall’s MET Breuer show was one of the major inspirations for me to start painting, the vastness of the work, the illustrative elements, the decoration, the storytelling, it blew me away. I’m also consistently in awe and jealous of Ida Applebroog’s work. Sculpturally Betye Saar is a big deal to me, and Pepon Osorio.

What is your current workspace like?

Chaotic isn’t even the right word. It’s cluttered, full of craft materials I’ve promised myself for years will end up being used. I recently saw a picture of Betye Saar’s studio, where all her assemblage materials were sorted by color and I was like, I should do that, and then I never did, and probably never will. I spend a lot of time working on the floor, and the wall (which is now stained with ghost images of paintings that went directly through the unstretched canvas and onto the wall). My desk is basically just decorative at this point, because I can’t even bear to clear a space to work on it.

Interview composed by Maddy Olson, Ruby Jeune Tresch, and Joan Roach