Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

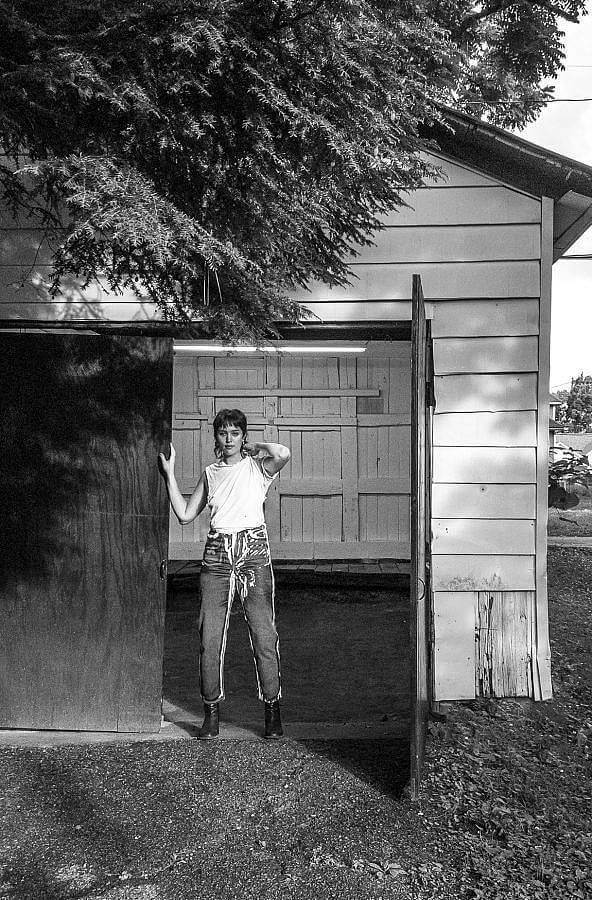

My name is Kelsie Conley. I’ve spent my life up and down the East coast, but currently I live in Knoxville, Tennessee where I am an artist, the Curatorial Assistant at the Knoxville Museum of Art, and the Director of the gallery space Bad Water.

How was Bad Water founded?

I moved to Knoxville from New York in 2018. With the move, I knew I wanted to start an artist-run space in Knoxville and met Marla Sweitzer, who was already living here and interested in finding a space to do so. Marla has since moved to California and runs Invernado Gallery out of her apartment with artist Christian Vargas and I’m on my second attempt to rekindle Bad Water. The first was thwarted partially by the pandemic and partially by the complete lack of certainty in my life at that point. Not even sure what the coming year would look like, I started reaching out to artists again this past fall for shows starting in 2021. We worked with a lot of friends for the first couple of shows in 2018, and several years later when I was going back into this by myself, I knew I wanted to extend beyond just people I had pre-existing relationships with. The life-giving part of running a space like this is the opportunity to make new friends, and how meaningful those new relationships are when they’re founded on something as full of connection as making a show.

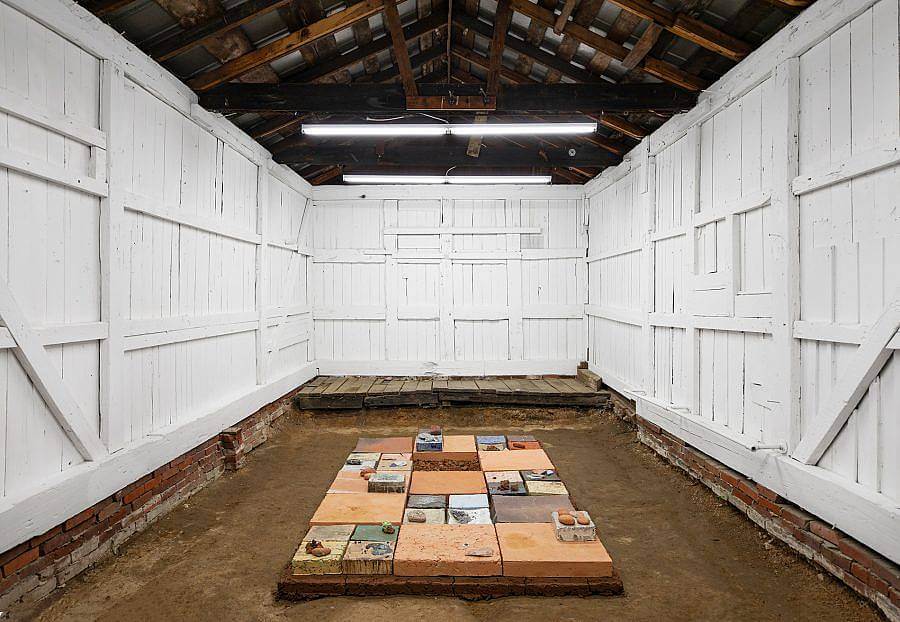

Bad Water is currently located in a garage with an interior reminiscent of an older barn. How does this non-traditional exhibition space contribute to a show and the gallery as a whole?

That’s maybe the most apt description of the gallery someone has given yet! From it’s exterior you would expect the walls to be something like plywood boards with a concrete floor, but when you’re inside, it’s a nice surprise to find these barnwood-esque planked walls with weighty pine beams and a clay floor. The architecture is dominating and it’s pretty easy for it to swallow the work entirely. This is always in the back of my mind, but for me, it bolsters the curatorial process rather than limiting it. Something about the architecture of that space feels more like world-building than just hanging some art up on some walls.

Can you talk about the process of putting together your first exhibition, Sister Genus by Colleen Billing?

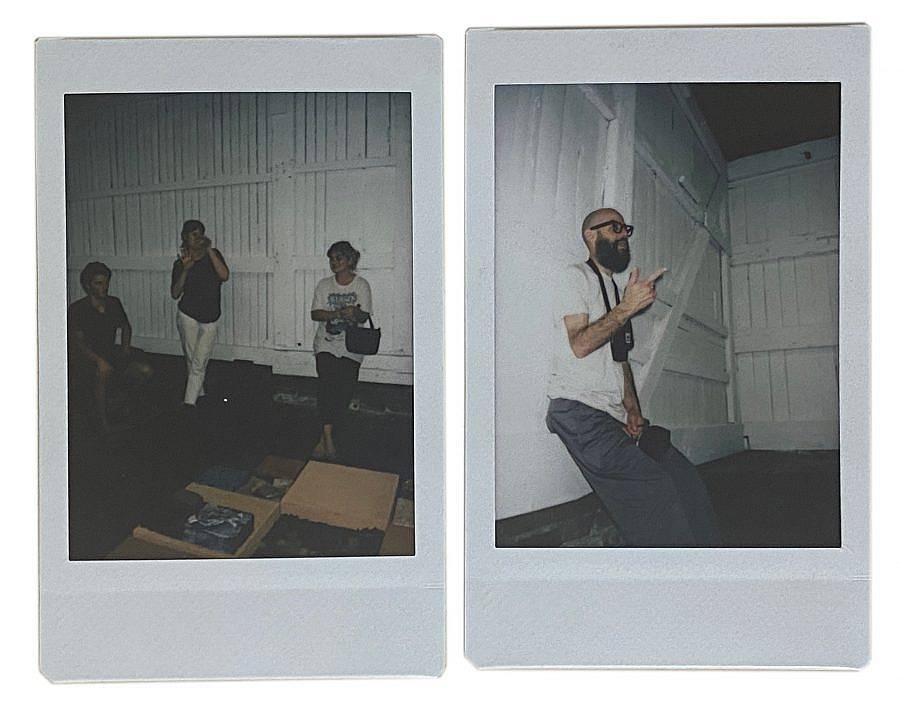

I look back on this time so fondly! I was still running the space with Marla then and we were truly thrown into our first opening. Colleen came down from NYC about a week before to finish the work on-site. I remember it feeling fully chaotic and fully invigorating. It was winter, unusually cold outside for the Southeast, and there was a big storm that blew the circuit box, so Colleen was installing the show by lantern and candle light in the middle of the night. A week out and we had not yet installed lighting in the space. I was naively trying to do the wiring for the fluorescent lighting with no electrical experience, beating my head against the wall watching Youtube videos trying to get it right. Ultimately losing power was a blessing in disguise, requiring an electrician to come to our house who showed me how to get the wiring done on the day of the opening. That show was full of last minute decisions and I like to think I have worked through enough of the kinks to help myself and the artists feel more at ease while still leaving room for things to change entirely if they need to. Colleen is also guest curating a two-person show of Esther Sibiude and Celia Lesh this coming July at Bad Water and I am very excited to have her back in town.

What unique contributions do you believe artist-run spaces in the South are currently making to the art world?

It’s hard to speak on artist-run spaces as a whole, or the South as a whole, but if I try to think on some commonality across the diverse artists running spaces in such an expansive region, I like to think that it’s encouraging people to make space in their communities for thoughtful engagement while simultaneously refusing insularity, refusing the notion that to be in the South is to be isolated, and refusing any expectations or generalizations. Burnaway and Number: Inc are both fantastic resources to learn more about the wide range of work being made across the South.

What influences have shaped your outlook on the potential of artist-run spaces?

I grew up in Florida going to DIY and punk shows in the mid 2000s. There aren’t any basements in Florida, so a lot of shows were happening in living rooms or garages. When I moved to Richmond, that was the first time I experienced art spaces in the same way I had experienced DIY shows—in people’s apartments, basements, and garages. It made so much sense to me that these things could operate in a similar fashion. It often feels corny to talk about how DIY or punk music has shaped my life, but it’s hard to ignore the ethos and energy it provided me at a young age. This is difficult to untangle from how I feel about artist-run spaces.

Can you share a bit about your current exhibition, Field Dug Over by E. Saffronia Downing?

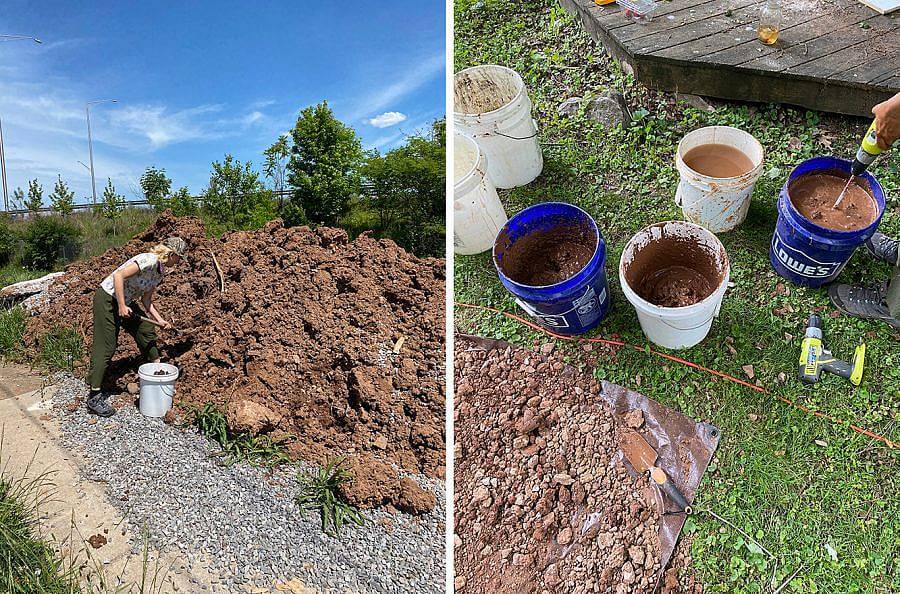

I was lucky to have Saffronia in and out of East Tennessee for almost two weeks, jumping around from camping in my backyard and working on the show, to camping in the mountains with her partner, Danny Goldberg, and back to my backyard again for the opening. I missed them immediately after looking out at my backyard and not seeing a pitched tent anymore. We started install on a morning about a week before the show and after shuffling around the work for an hour or so, we realized that it was calling for something else. After a couple hours, some tamales, and a brief hike—we conceptualized this foraged clay platform that the work would sit on. We filled up the back of my truck with dirt, processed the clay, made the mold, and pressed it all within the day. It was my first experience making clay, and although I’d talked with Saff about the work, my hands a foot deep into a bucket of wet clay gave me an entirely different perspective. It was a privilege to be able to ask Saff endless questions about the process and materials she works with. The show may seem so much about material, but it’s important that the immense historical and site research Saffronia does is not overlooked. On the last day of her being in town, we drove out to a secret quarry for a swim, and it was incredible to me that Saff was recognizing some of the working quarries we drove past and was able to locate herself from the research she had done prior to coming.

What goals do you have for Bad Water moving forward?

Honestly, the most pressing goal for me right now is practical rather than dreamy. I would love to figure out something more financially sustainable for myself while continuing to cover as many costs for artists as possible. Right now, that constitutes shipping costs, publication costs, installation costs, buying dinner when artists come into town, etc. —and in my dreams this would extend to a stipend for time & material costs as well. I work full-time on top of doing this and most of my disposable income goes towards the gallery. Without going through the non-profit process, funding is difficult. I hope to be able to find a way to provide as much for the artists I am working with as possible.

Do you have any advice for artists interested in opening exhibition spaces?

Trust your gut! I’m a virgo so these stomach feelings guide a large part of my life and usually don’t steer me wrong. Bring your own knowledge and understanding to the space, but also a willingness and openness to collaboration and learning. Brace for it to consume a lot of your time. Practice generosity (my friends & mentors in Knoxville really taught me this one, thank you all) with artists you want to work with, the community that directly surrounds you, and the people that support you from far away. When my friends who teach at the college here take their undergraduate classes to come see the shows this question inevitably comes up, and my advice is always just to send the email. A mentor/friend told me that sending the email only feels corny and cheesy until the person says yes and I’ve learned that he was 100% right about that.

Interview composed and edited by Ruby Jeune Tresch