Lee Schulder: Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do

Rachael Bos: I’m from Salt Lake City, Utah. I’ve lived in Chicago for about five years now.

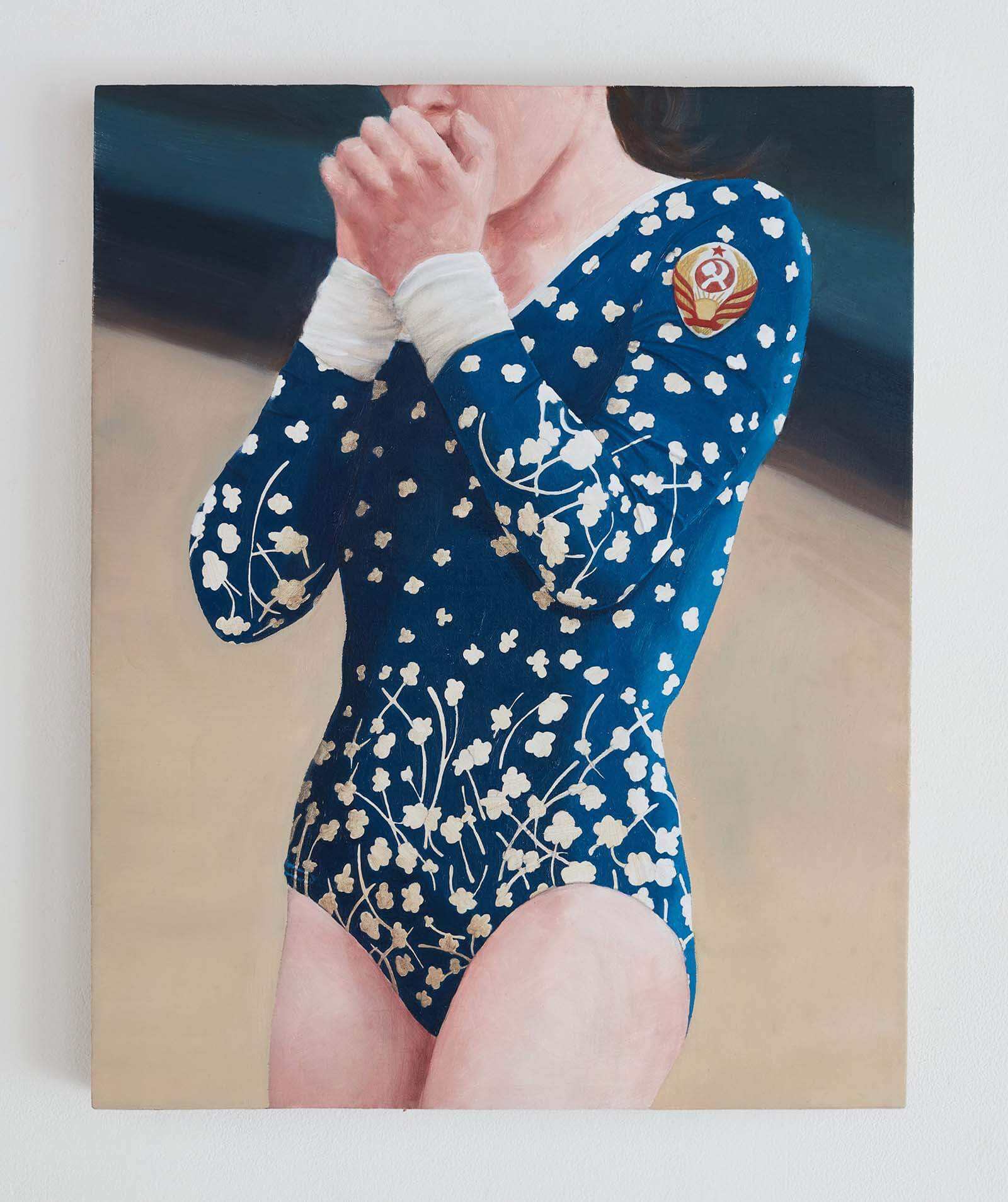

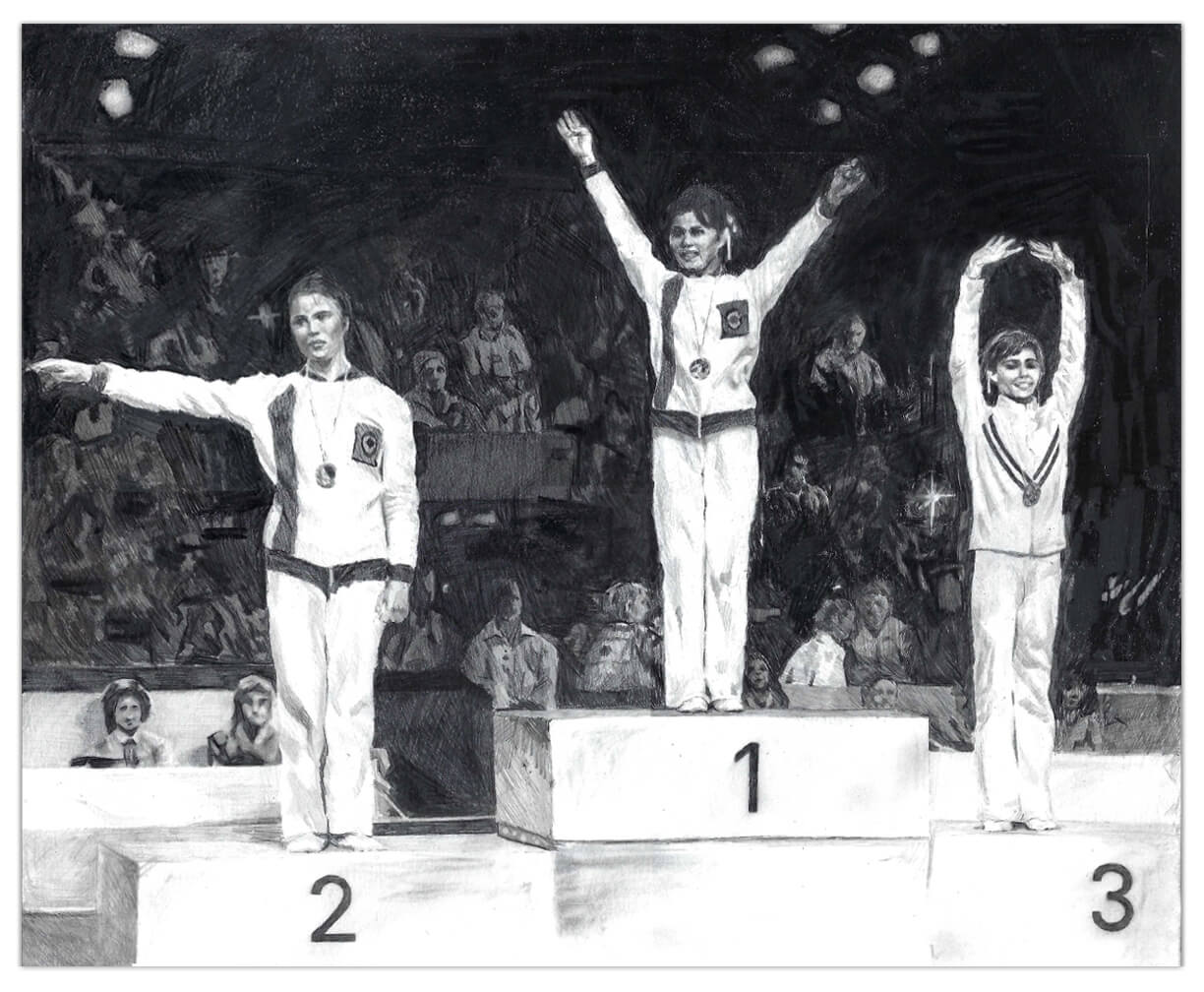

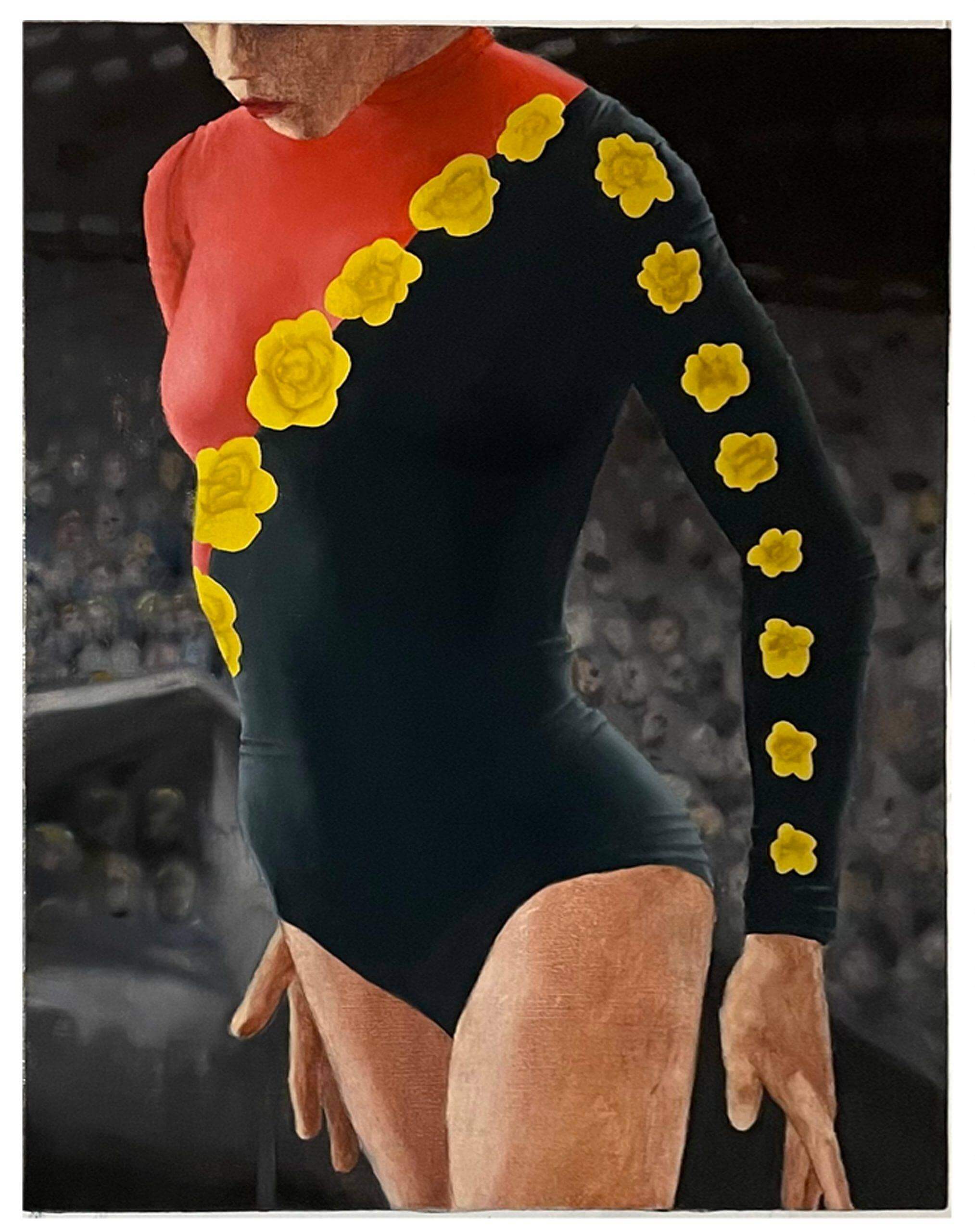

I came here to go to SAIC. Recently I’ve been painting leotards and Olympic imagery.

LS: How did you get started painting the Olympics? What drew you to that imagery?

RB: It started when I was watching the 2020 Olympics, everything seemed so beautiful to me. Like in the midst of the pandemic, just the artistry that goes into like, you know, gymnastics, like all of it, it’s just like incredible to watch. You could pause it and everything looks like a painting or a sculpture. It’s incredible. It’s like the top physical condition of the human body.

LS: It’s like the “this is what peak performance looks like” meme but it actually is what peak performance looks like.

RB: One of the coolest things that I learned during my time at SAIC was from Tony Phillips, who told me that I need to think about my practice the same as an athlete. You have to develop a really good athleticism to be able to make really good and consistent work. You have to build up a stamina for being able to work long hours, and you need to know when to be able to take breaks and to be restrained, and then you also have to build up a bunch of muscle memory so that when it’s time to execute, it’s just perfect.

LS: So when we talked before, you mentioned growing up in Salt Lake City and watching the Olympics as a kid, if you want to talk a little bit about that.

RB: Growing up in salt lake city there’s not much to do and growing up, it was never a cultural hub for anyone but Mormons. But when it was the Olympics, they would do the trials there. My mom would bring me and my brothers up, like we would go at nine o’clock at night in the middle of winter– and it’s freezing. But you watch these people just bolting down moguls and doing flips and stuff. You never really get to see that in person anywhere, and you see all these cameras. So it always felt like something really special was happening.

LS: It’s interesting because it’s not like you watched it and then immediately wanted to paint it. It took a while to marinate.

RB: Yeah, I think it was like, a lot of people are like, you need to paint really personal stuff. And I really don’t want to be painting about, you know, my heritage, like how boring. When I realized I was like, oh, I’m actually really inspired by seeing these growing up. It was really cool to put it together. I think it is a big realization that nothing is completely separate from yourself. Your interests will always reflect part of your history.

LS: You use a lot of reference imagery in your work. Can you tell me about your process for finding the images?

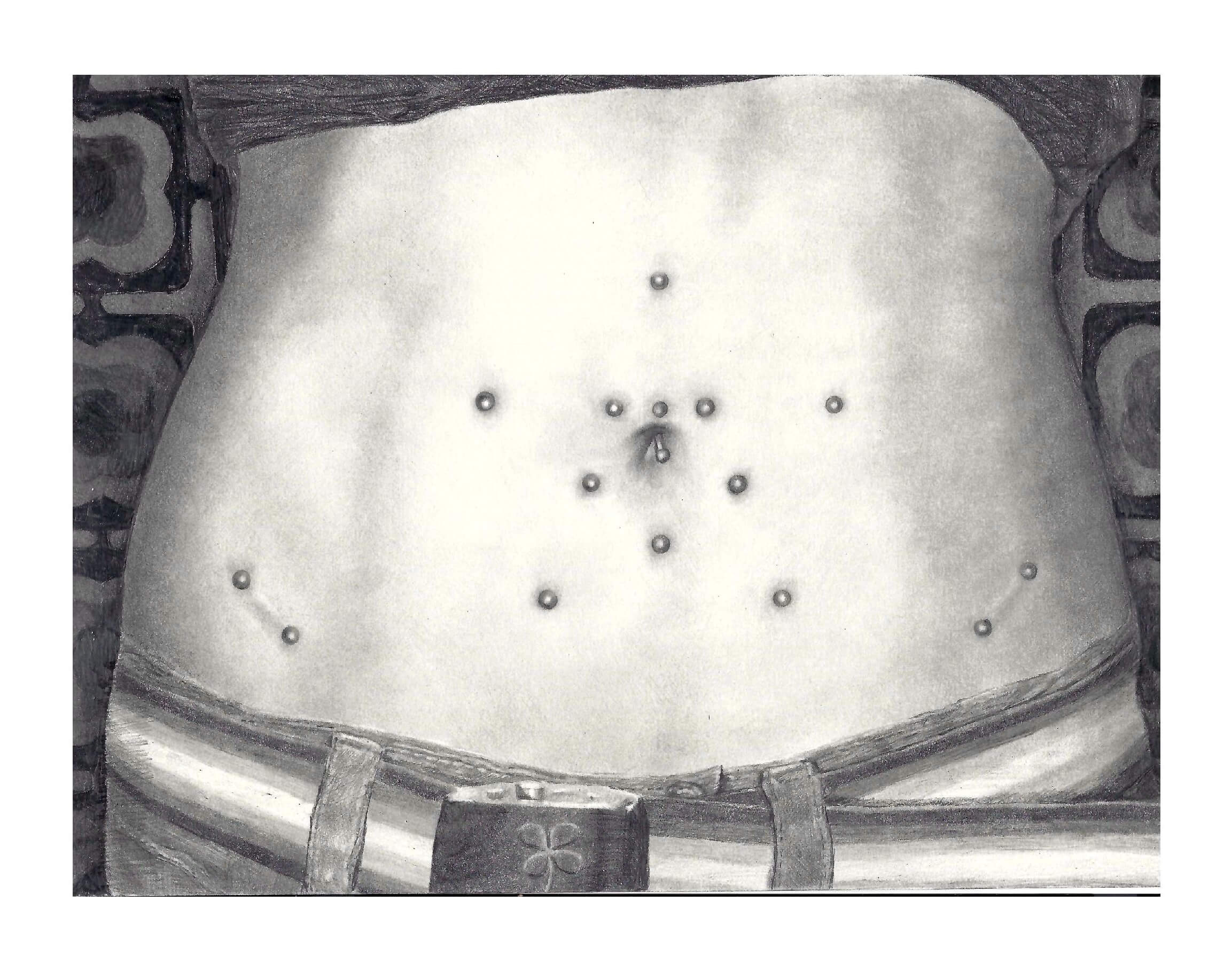

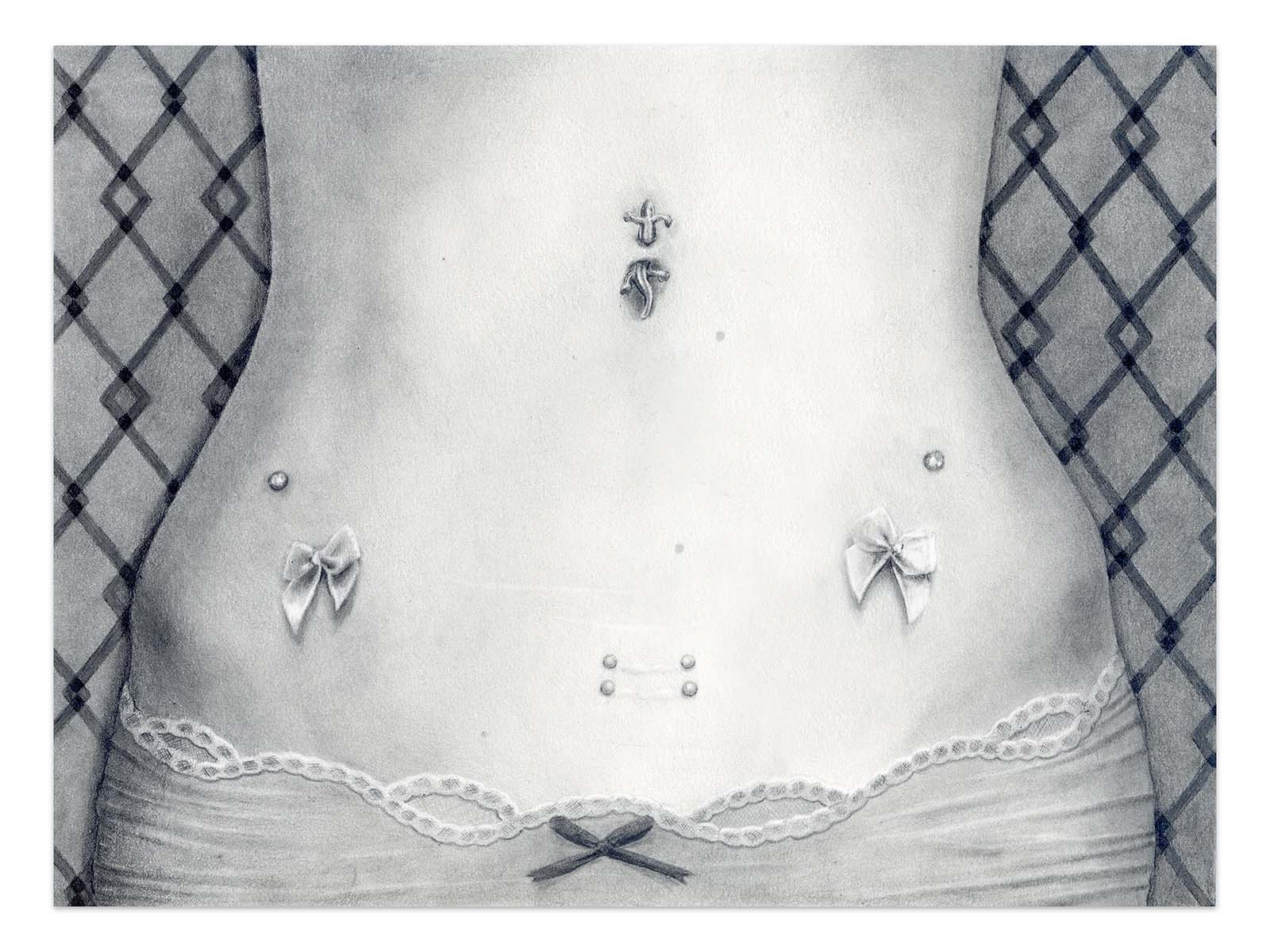

RB: I think it’s probably one of the most important parts of my practice. I’m really influenced by pop imagery in that kind of sense, and by having a lot of the artistry lie in your choice of reference material. So the way that I go about collecting my reference images is that once I find a subject, it’s important to find the best sources for that imagery. With Olympic imagery, they make a film for every single year of the Olympics and they’re all on criterion. So I’ll go through them and I’ll just screenshot and screenshot and screenshot. And so now I have all these reference images. But then there’s stuff like piercings, where you can’t go to an influencer’s page on Instagram. You have to go to the cringey 15 year olds’ Pinterest page of piercings they want to get when they’re 18 and go through all of these really strange and impractical piercings.

The way that it happens is that I got very, very, very obsessive about it and it’s not even really about context and information. It’s really mostly learning the language of the imagery and finding that visual language, and then sort of learning how to speak it. So then you can create your own characters.

LS: I love hearing about how you find the piercing images because I feel like people don’t understand how much stuff there is on Pinterest. Like when people think of Pinterest, it’s very much associated with like, twinkly lights and mason jars. But there are a ton of Subcultures and really anything you could ever want to find is on Pinterest.

RB: Their algorithm is the best algorithm on the internet, I think. It’s like on Instagram, you can find a lot of the same things, but they’re kind of posted ironically. Even though I do approach kind of cringey subject matter, like with the piercings, I never approach anything as ironic. I love everything that I paint.

LS: You recently had a solo show at H.G. Gallery called Oh Sport, You Are Peace! Can you talk about the narrative behind that title?

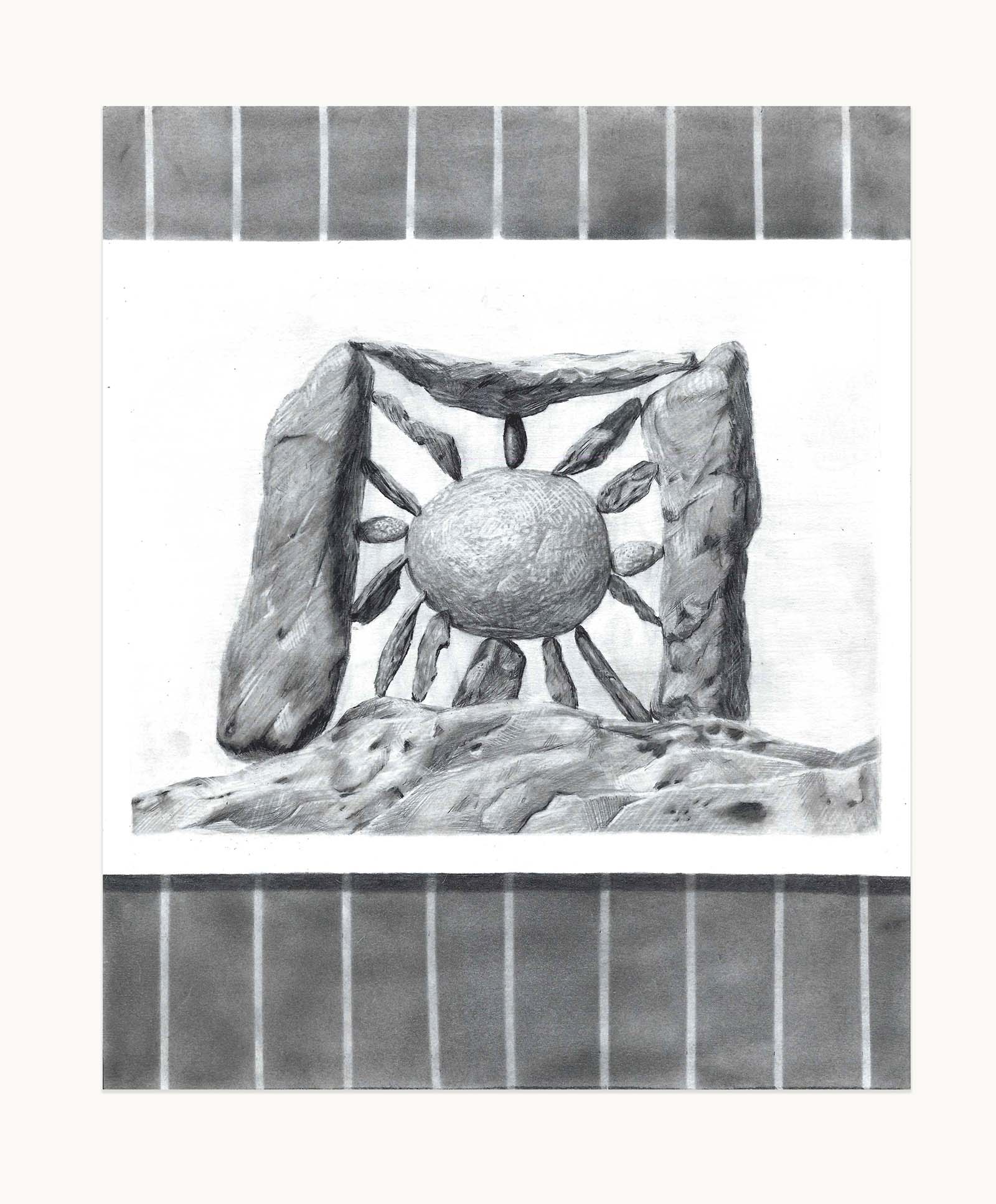

RB: The title comes from the film made of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, Oh Sport, You Are Peace! The 1980 summer Olympics were very controversial because the United States and some other countries had boycotted the Olympics due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. I’ve seen a lot of the Olympic films so far and I still have a lot to go because there’s so many. It’s probably the most straight up absurd film out of all of them. It’s just lots of backhanded, passive-aggressive comments about America, and then the most ridiculously like excessive imagery and really weird stunts. Like a 15 level human tower, you know, and like a million people just holding up signs of Mishka the bear. It was also the first one I saw and it introduced me to Olympic films, so I have lots of screenshots from it. I think it’s probably one of my top five films ever, and you can find it for free on YouTube.

LS: What do painting, portraiture and figuration offer you over other mediums and thematic approaches?

RB: I think it’s a very unique position to be an oil painter in 2022 because you have so much history to reference and you have to know how to make it work for you and not against you. So I think that it’s really helpful to be very nerdy about the history and to be able to reference it. It’s just like, if you can reference stuff, it can make your work have another level.

I avoided figuration for so long. I was just doing trompe l’oeil and I was very focused on just objects. There’s such a history with figuration and so it’s really intimidating to approach the figure, but there are so many cool ways that people are doing it right now. So the way that I wanted to approach it, I really like making work that isn’t about specific people, especially not myself. I was really inspired by Lucy McKenzie and her exhibition, Inspired by an Atlas of Leprosy. It’s just all these rooms, like a trompe l’oeil house. It is figurative work in a way, because there’s definitely an implied owner, but the only thing you know about them or what they’re like is entirely depicted by their taste.

There’s a way that it was put that I like. “The characters are only understood through their markers of taste.” And so I like these characters that are like anti characters. It’s like my work with the piercings, I take a number of reference images and will mix them up. But I feel like there is a very specific person, a very definite character, but they’re only understood by like the markers of their taste. And I think that our generation specifically, people in their twenties and thirties, can tell a lot about these people by their tastes and these piercings. Because a lot of them are very much…. I’d say early 2010s.

LS: The stomach piercings especially, I know exactly what that person looks like just from the stomach. So aside from Lucy McKenzie who are some other artists that you consider influences?

RB: Vija Celmans, I found her at a very perfect time of my life, where I kind of needed the inspiration to make very realistic and obsessive work. And knowing that she was doing it in the time period she was, I was like, if she can stand up to professors trying to make her do abstract, I can do trompe l’oeil at SAIC.

Coming from Utah, I really wasn’t exposed to any level of art at all beyond paintings of Jesus and Joseph Smith, so it took me a while to come to terms with the fact that I actually really do love to do just extremely representative work in a very traditional style.

And then Lucy McKenzie, I’ll bring her up again. Her breakfast trompe l’oeil was done in probably the most contemporary way that I’ve seen. It’s just so inspiring, and she doesn’t put art and design in a hierarchy, which is so important to me. She spends so much time actually researching these really old and kind of outdated skills that she went back to school for the decorative arts, which is so cool. And then other modes of figuration I’ve been looking at recently, Emma Stern and Catherine Mulligan. I really love what they’ve been doing.

LS: Changing the subject a little bit, you recently co-curated your first show at Heaven Gallery. What was that process like?

RB: It was really interesting because I formed a very different relationship with the work than I usually do. What I really liked about it was that it was definitely like a puzzle and it was a lot of problem solving. And I realized with a lot of my work, a lot of it is just compositional problem solving. But I think I’m definitely better at more technical aspects of curating, like finding out where things should go and lighting and all of that, rather than logistics like coordinating and writing.

LS: Do you have any upcoming projects?

RB: Yeah. So I’ve been working on making my piercings bigger paintings, which is definitely opening things up a lot more for me. And then I’m working on an enormous, nine feet by six feet red track suit. And in a way that’s like the cropping of the leotards, but just expanded and includes two more implied figures and then a fully articulated environment.

I’m also doing more leotard paintings. I need to do one for an upcoming group show I’m going to be in this fall. I’m also looking at other types of uniforms, like tennis uniforms and speed skating.

LS: It’s cool being obsessed with something that has so much reference material that you can just kind of paint it forever and still not even get to like 5% of it.

RB: Exactly. Like I’m going to be working on this for so long. There’s so much within this realm, I haven’t been bored with it at all.

Interview composed by Lee Schulder

Interview edited by Lee Schulder and Jo Roach