Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I’d much rather be asked what I am into, but I understand that this isn’t that kind of publication.

Can you talk about the relationship you have to queer abstraction?

I’ve got to say, queer abstraction and I are on the rocks, and that’s how we prefer it. The tension between queer iconography and queer abstraction is constant and maintained within my work, and admittedly in my everyday life. It has always been a queer project to steal away iconographies and reformulate them as needed; to find oneself reflected within an othering and hostile world as a strategy of survival, of self-care, of pleasure. Alternatively, queer abstraction is theorized to offer unforeseen potential in afiguration and can allegorize social concerns through formal relations.

Perhaps it’s my hedonistic tendency, but why not have both? Aren’t they two sides of the very same coin? Better yet, isn’t queer iconography often the result of abstracted, misused, and repurposed facets of normative mainstream culture? There is nothing fixed when it comes to identity. Bodies are constantly becoming more fluid, fucked with, and tactically mediated. Why then would figuration pose the threat of legibility when the figure is already an abstraction of the thing it’s suggested to represent?

In your recent work, you’re pulling from an archive of queer publications. Looking at the complex history of queer desire & the history of HIV/AIDS, what’s the significance of using these images?

A child of the ’90s, working with images of pre-HIV/AIDS-sex and sexuality comes from my desire to better understand the complex network of aesthetic and political influences that have effectively shaped me. It’s an exercise in withstanding the seemingly divergent pull of nostalgic longing and queer futurity, one tied to my ankles, the other to my wrists.

In “Becoming Utopias”, Jacqueline Rhodes characterizes queer archival engagement as the “self receiving an echo of itself from the past—an interaction with history from which one returns to oneself changed, refracted somewhat, and through which the past is also reflected, returned to itself afresh.” The performance of a queer utopian memory lays bare the limits of today and awakens the possibility to imagine tomorrow. What lies in the tension of looking back and moving ahead?

Introduce us to your new work “Tough Love.”

The installation consists of a queer club and kink-scene image imposed onto the surface of an architecturally scaled nickel-plated ball chain curtain hung on a modular structure. The curtain, a monumental feature of public cruising sites, sex clubs, and back rooms, is re-envisioned as an experiential threshold to queer imagination and projection. The structure, composed of stage flats painted matte black, creates a void, a lack, an empty space brimming with potential and anticipation. The work transforms the physical site into the psychological and performative space of speculation. Through the pixelation and material translation of the curtain, the image is rendered porous, open, and fragmented, its referenced history ruptured and destabilized by the viewer passing through the cool and heavy beads.

I remember wearing next to nothing. It was hot. The middle of July. And upon entering the bookstore, the sunburn radiating from my skin was the only thing keeping me warm in the AC. He got a booth in the back, put a few dollars in the video machine and was waiting for me ass up in Booth 3. The icy steel beads kissed my bare shoulders as I walked through the ball chain curtain to find him. I crossed the threshold for the first time and pleasure was all that lay before me.

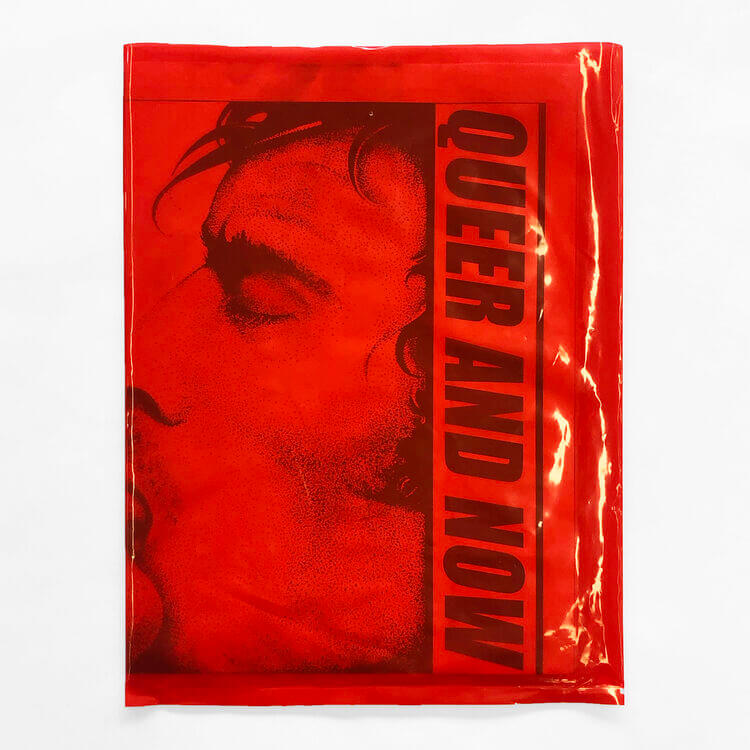

Tell us about your publication Queer and Now.

I wanted to give form to desire, so naturally, I looked to gay personal ads to influence the publication. Those pulpy, explicit and anonymous two-bits found in the back pages of porn magazines were a source of community engagement through expressions of hyper-specific sexual desire. However, the connection I long for with this publication is a little different.

Bringing together personal narratives, first-hand accounts, and appropriated critical texts, Queer and Now bridges the irretrievable past with the unimagined future in the form of the personal ad. This past year, many of us developed the need to connect with our communities in new ways despite mandated isolation. Interviews with Leathermen, ACT-UP members, and art fags about their experience through the HIV/AIDS crisis gave me a new perspective on the current socio-political climate and global pandemic. This work connected me to a generation of voices that I once felt alienated from. Together, these multiple perspectives create an atemporal, non-monolithic meditation on desire, agency, and belonging, couched in a structure of possibility. If you get a copy, don’t forget to turn it over for a little surprise!

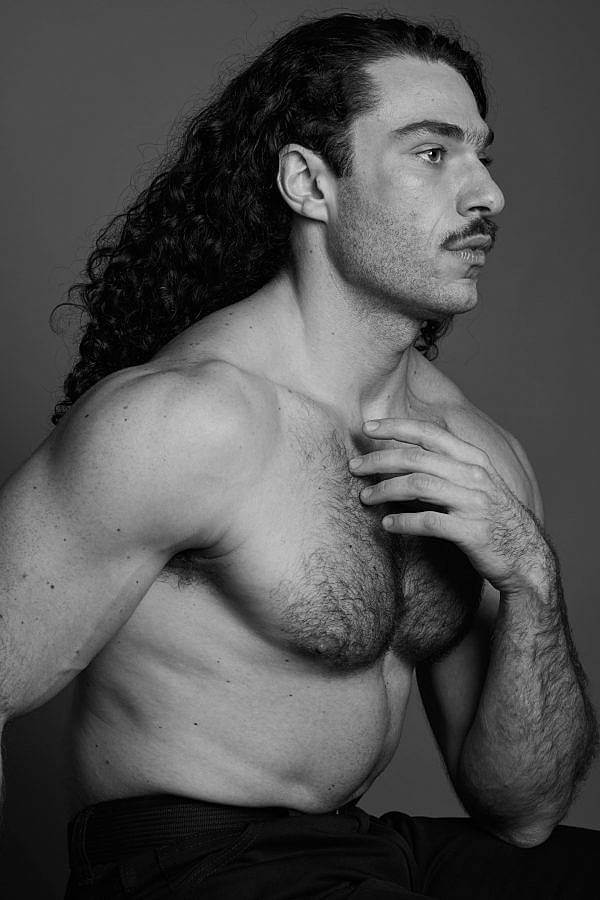

Introduce us to your exploration of the world of athletics as it relates to western queer representation.

At surface value, my interest in the gym is related to athletic kinks, cruising, hyper-visibility, and gender construction. Surrounded by mirrors and positioned on stages, bodybuilders and physical fitness enthusiasts push their bodies to the limit and enact a moral performance of health and wellness. I am drawn to the maintenance, transgressions, and limits of the body. However, the dominance of muscular bodies and their images has a dark past within queer history. Signaling wellness during a period of illness and suffering, the muscular body gained its position as an ideological norm in opposition to the ailing bodies stricken by HIV/AIDS. It’s a fine line I walk, either celebrating the malleability of my body or recapitulating this internalized fear.

In “Tough Love” & “Bound by Glory”, you’ve built upon the legacy of Gonzalez-Torres’s curtain works. How does employing the curtain play into your intentions for these projects?

Formal quotation is at the heart of this series. As I look back to the radical time in queer history that centered pleasure against adversity, it feels only appropriate to follow that motivation to the political artwork being made concurrently. I align myself within a legacy of queer abstraction and minimalist quotation that sought social and political change. The work of Felix Gonzales-Torres responded to the HIV/AIDS epidemic by transforming queerness from a marker of difference into one of familiarity, but familiarity is not what I am after. It is the irreconcilable that interests me, especially when representation is easily misinterpreted and misused as an accurate reflection.

Gonzales-Torres’s curtain works are delicate and playful despite their grave reference to absence. They hang clear across the gallery space and demand engagement. My curtains don’t demand, they seduce and proposition. They don’t delineate space, they create it. To pass through them is to consent to their transformative potential, and that’s not for everyone.

What are you reading right now?

*Looks at the massive pile of unread books at his bedside.*

At the risk of sounding like a cliché, I started reading Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Gay Bar and Jonathon Weinberg’s Pier Groups. Both books approach discussions of threatened queer spaces and subcultural belonging throughout history and the significance their memory still holds for us today.

Any upcoming projects?

I am excited to say that my sister Francesca Gentile, Ph.D. and I, have been offered an opportunity to write for a special issue of QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking for their Winter/Spring 2022 periodical. Focusing on the sculptural experience as a queer logic of exchange, our forum article will center my work within a greater context of contemporary rhetorical theories, namely rhetorical listening and nonidentification. Plus, who doesn’t love to rehash adolescent sibling rivalry as an adult? Count me in.

Other than that, I am keeping up a good clip in the studio towards an exhibition in St. Louis next year and teaching at Tyler School of Art and Architecture in the fall.

Interview composed and edited by Joan Carol.