Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I am a biracial artist in a close relationship with place–driven by a larger act of orientation and observation, simultaneously obsessed with all of the sensorial bits that come from new environments. With any kind of mapmaking and telescopic representation, subjectivity and memory insert themselves into topography in necessary and often disruptive ways. I’m interested in describing points where these narratives fuse.

Through field studies, maps, and monuments of an in-between space, my practice is some kind of cross between rambling and gardening the reliably imperfect anecdote of belonging.

Can you talk a bit about your current exhibition “To Raise A Blister From Afar” at Below Grand Gallery in New York?

The title To Raise a Blister From Afar is pulled from a short piece I began writing in 2021. In three parts, it described a pilgrimage of the reader and their perfectly adept double (cross between an avatar, a doppelgänger, a sister), who is simultaneously trudging alongside while beckoning from some semblance of home. Compelled by distorted longing and marked by abjection, the individual/s move through the fuzzy unfamiliar with a desire for a single delineation.

To Raise a Blister from Afar presents these dichotomous narratives and fragmented, abstract associations as part of a larger ritual of becoming, where inability to mime source becomes its own faculty and the seams of becoming can be relished.

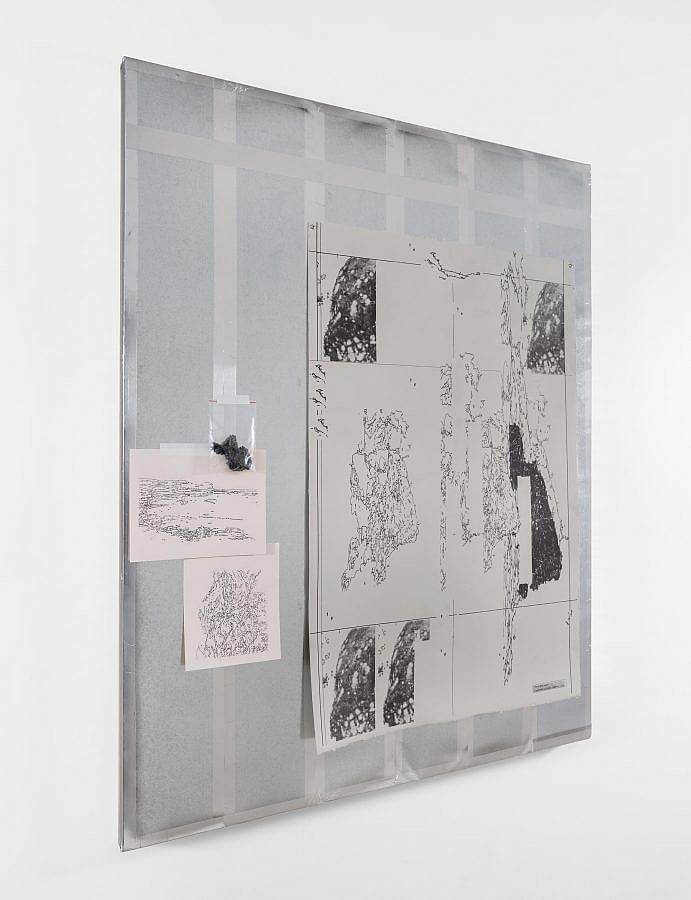

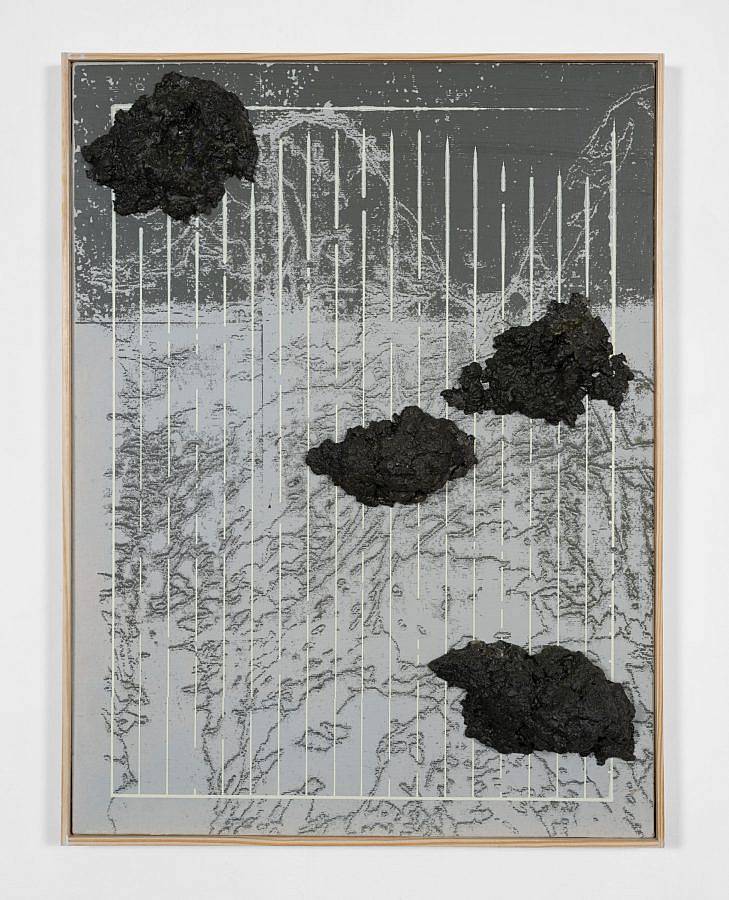

The show consists of a large window space shrine, carpeted with seaweed laver and stocked with samples of artificial nature (their original counterparts both missing and irrelevant), watched over by a single-paned aluminum flashing altarpiece. The second interior space functions as a reliquary of receipts, objects, and maps that obfuscate their source material and present glitches as functioning syntax.

Many of your pieces are assemblages of multiple smaller items and processes. What is the typical timeline of the assembly of your works and do you typically hold onto specific items for a while before they make it into your works?

Speed is something I’m continually trying to reconcile in my studio: there must always be one slow, nurtured project, and a handful of smaller things completed in a fast turnaround, as if I’m feeding something insatiable. These smaller components are most often screenprints, cyanotypes, and cast objects. Seasons of gestation and planning are the slowest part of the trajectory, so inevitably these periods lead to overgrown kaleidoscopes which I’ll draw from later.

Can you talk about your process of using three dimensional objects to break the picture plane of wall works?

These intersections, either blockades or diametrical planes, describe breaks in conversations due to missing information and a generally shaky grasp on the language itself. These moments of incapability disrupt not only the exchange, but a kind of holistic cultural and racial passing. Recently they’ve taken the form of labels, as if to poke a bit of fun and historicize the moment.

What have you been reading lately?

Generally I have several heavy(ish) books that I pick at for research, and one easy reader to balance it all out.

I’m currently playing musical chairs with Manifestly Haraway (Donna Haraway’s manifestos/conversations with Carey Wolfe), An Inventory of Losses by Judith Schlansky, Slow Reader: A Resource for Design Thinking and Practice (Ana Paula Pais and Carolyn F. Strauss, eds.), The Language of the Night by Ursula Le Guin, and C.S. Lewis’ Till We Have Faces as the side snackie.

You have spoken about your works beginning with renderings of Japanese topography. Can you describe your connections to these initial points of reference?

My virtual walks via Google Maps usually begin with the objective of aligning a particular memory with an ostensibly objective lens. This practice first began when I remembered my first trip to Japan and began looking for a specific roadside shrine down the street from a convenience mart (this led to mapping and arduously filtering all convenience stores in that particular city). Once I’ve located these places, I will end up veering down side quests that lead me to places I may have no memory of or have not physically explored. This practice of aligning narratives allows me to parse my own desire for authenticity and familiarity.

Can you talk about the way that visual transference operates in your practice?

I’m interested in the ways that transfer processes can describe code-switching, failures in orientation (misregistrations), and the guiding, sometimes dicey, matrix on which everything sits.

Drawing and printmaking are both comprised of seeing and translating, often through a fixed frame and with the aid of a mechanical intermediary (the hand included). Through these methods, I’m able to rehearse a kind of desire and illustrate the ineptitude and loss that comes from compression.

How would you describe your relationship with casting?

The decision of which objects to cast is intuitive, swayed by visual characteristics and any desire to suppress these in their reproductions. If any attribution is removed and its constitution changed, will the castings conjure the visual archetype of the parent object? Or can they assume some kind of indexical power of the environment in which they are placed? Authenticity and the significance of source can then make way for new meaning and context.

The process itself is mercurial–a gloriously indulgent gift that also can be a bit of a thorn–depending on what kind of energy is brought to the table. The construction of a mold is a strain on one’s patience and can often feel like a pit of misplaced effort, while the casting itself can be a real gamble with precious, expensive material. The entire operation can and often does form a kind of pinnacle of anxiety in the slowed grind of a project. But when everything goes accordingly, casting feels like discovering and unearthing precious gemstones and you’re propelled to do it all over, again and again.

What is your favorite post-studio meal?

A whiskey, neat

Any upcoming projects?

Next month, I’ll have a 2D-ish piece included in the Sanford Vitrine, a display co-curated by Estefania Araujo Bianchi and Natalia Janula, located towards New Cross in south London.

Interview conducted and edited by Sam Dybeck.