Tell us a little bit about yourself and describe your practice.

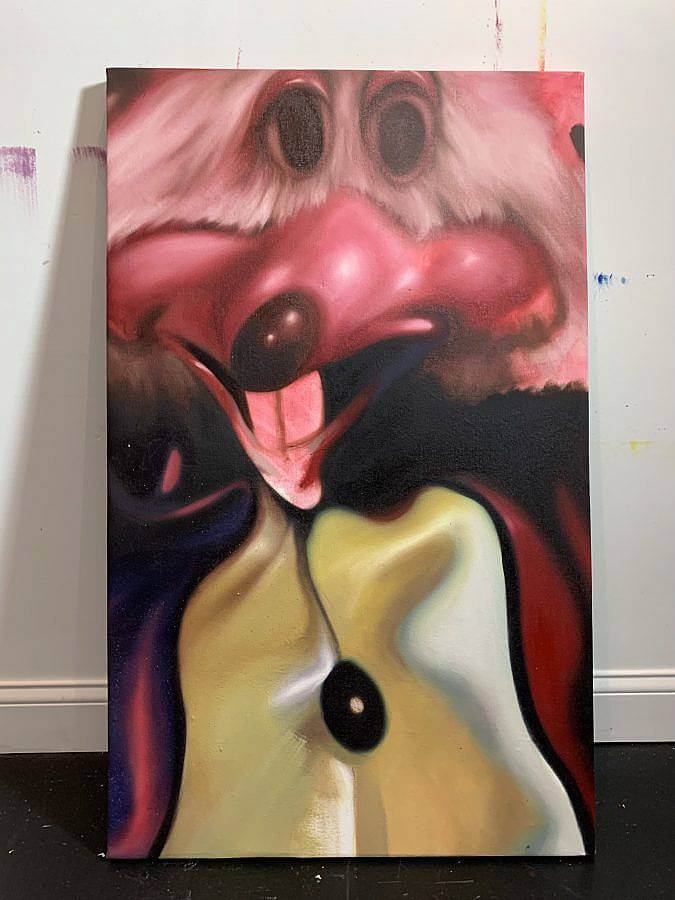

I am an oil painter born and raised on the West Side of Chicago. My process for finding reference images has changed a bit over the years. I’m always surfing the web for images that have a certain aura or reflect a vintage aesthetic, and once something catches my eye, I begin to break down why I’m drawn to that particular image, and that’s where the process begins. For example, I found an image of Chuck E. Cheese from the 1970’s, back when animatronics were a big deal. The image caught my attention because it was such a huge contrast from the version of Chuck E. I remember growing up seeing. When I started doing some research, I found the rest of the crew of characters. I vaguely remember seeing most of those characters, but making that discovery I began to have a moment that felt similar to a fever dream.

Can you tell us about your creative process and the Real Hood Monsters?

The Real Hood Monsters is a brand I created back in 2016/2017. Thinking back, I honestly started playing with the idea of objects/food coming to life when I was in middle school. It was probably one of the many ideas that came and went around that time, but it found its way back into my life as a more developed version of itself later when I started painting more seriously. The idea was to create a universe of monsters that coexisted with humans in a post-apocalyptic world, and I created a short claymation directly linked to the Real Hood Monster characters starring in each short. I’m developing more episodes.

What/who is the biggest influence on your work right now?

As of recently, I’ve been watching documentaries on the pop art era (basically starting from the 1950’s). I feel like my current body of work is influenced by artists from that era. I’m greatly influenced by that time period in general. The styling at that time, the old grainy footage, the early ages of mass consumerism and its effect on America then and now. Advertising and Commercialism [is such a big part of the American visual language], its origins and relationship to pop art, eventually led me down a deep dive into the history of McDonald’s. McDonald’s, being an American staple and having really significant symbolism in American culture, became the centerpiece to my concentration because of its incredibly rich advertising history from the 1950s until present. I focus a great deal on the 1970s, when McDonald’s introduced the “McDonaldland” characters.

What do you want a viewer to walk away with after seeing your work?

I remember the first time I watched an episode of Black Mirror. The feeling I got towards the end of the show was so bittersweet: a mix of emotions; a thick feeling of discomfort. I can’t really describe the feeling in one word, but I’ve kind of become addicted to that sensation. It’s almost like an adrenaline rush. Similar to Black Mirror, I want my work to act as a mirror in the sense that it causes the viewer to analyze oneself. I want my work to feel subjective, not sure. When someone sees my work I don’t want them to know how to feel. If they feel anything I want them to feel a mix of emotions, having to deal with the line between reality and unreality, comfort and discomfort, familiar and uncanny. I want those feelings to sit and linger with you long after seeing one of my pieces.

Is there anything you collect that contributes to your work?

I weirdly collect my receipts from fast food restaurants. I don’t know what I plan to do with them. I don’t even know if that really contributes to my overall concentration, but I collect them.

I know you grew up on the West Side of Chicago; how do you think the art scene in that part of the city is different from the art scene in other areas of the city?

To be honest, when I think of the West Side, I don’t think of an art scene. Maybe that needs to change, or maybe I need to get in tune. There’s a vibrant music scene out West that I’m appreciative to have experienced while growing up.

What do you do when you’re not working on your art?

I’m always trying to find myself outside of constantly painting. I love finding new things outside of the studio that excite me and bringing that experience back into the studio. I spend most of my free time with family and close friends. I enjoy traveling and going on adventures, both within and beyond the city.

I know you’re a bit of a night owl when it comes to working in the studio, is that something you prefer?

Yes! I love working all night into the morning. It’s so peaceful, I have the best ideas and the most energy. I don’t know why the middle of the day during the work week always gives me some sort of anxiety. I think most artists would agree, that’s when the magic happens.

How does your use of oversized figures and subject matter inform your action packed compositions?

I think they go hand in hand, in the sense that most of the figures in my works are represented as larger than life. These characters are well known across the globe, not by mistake. The repetition of this constant, in-your-face style of marketing done by agencies tends to suffocate the consumer. My way of translating that in my work is by utilizing the entire space on the canvas. The Hamburglar painting I created last spring is a good example of this. The Hamburglar’s warped face is stretched across the entire canvas–I wanted it to feel suffocating. As far as my compositions, I feel that my earlier work was less focused on one specific subject. I had plenty of ideas I wanted to convey, but didn’t know how to spread them out through a cohesive body of work. I would put them all into one piece, and that’s what led them to become more action-packed. I’m focused on giving more time and attention to each complex idea, giving them all their own time to breathe.

Are there specific indications that a piece is finished, if so what would they be?

Complete exhaustion. I usually start a piece with the intent on painting it to one-hundred percent completion. However, I don’t feel I’ve ever actually reached that goal, not even once in my entire 10+ years of practice. I’m beginning to lean into the incomplete look, thinner brush strokes, completely untouched parts of the painting. I think those unfinished moments make my work feel more human. I also feel I can develop that process a little more and eventually incorporate the “unfinishing” with the same intention I do with every brush stroke.

What does an average day living and working in Chicago look like?

Everyday is different. A perfect day would start early in the morning with espresso and exercise. Writing in my journal. Towards the middle of the day, a stop by my Mom’s house to spend time with my family. Once it gets dark, traffic starts to slow down, then I go to the studio. It’s not always work work work, sometimes friends come by and we just talk and listen to music for hours before I begin painting. I end the day painting until the morning, then drive back home before traffic starts to get thick.

What is the ideal setting you see your work displayed at?

One goal is to see my work displayed in museums across the world. I grew up here in Chicago; visiting the Museum of Contemporary Art was always a unique experience for me. Even though I usually felt a disconnect from what I saw there, certain exhibitions made me feel as though my work could be shown there one day. I remember one time walking into a big white room with pitch black silhouettes across each wall. You could tell pretty quickly that they were set during the earlier days of slavery. The imagery was grotesque, potent, and very detailed even though it was only a silhouette, and you were immediately immersed into a storyline. The artist, I learned, was Kara Walker. That experience really changed my approach to my creative practice, but it’s also inspired me to think of what it would mean to display my work in a museum one day–how would it look or what I would want to say.

Interview conducted by Ricardo Partida and edited by Natalie Toth. All images courtesy of the artist.