Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

Hello! My name is Mathew Zefeldt and I am a painter who is focused on painting constructed virtual worlds, like video games. I also serve as an Associate Professor of Painting and Drawing in the Department of Art at the University of Minnesota. I am originally from California.

Can you talk a bit about your latest solo exhibition “Re_Spawn” at The Hole in New York?

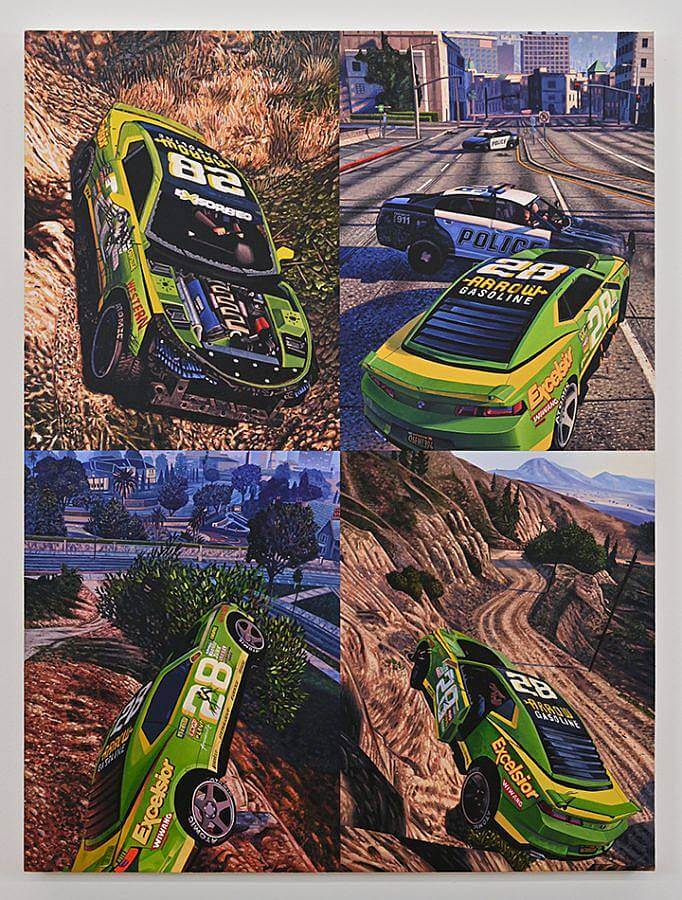

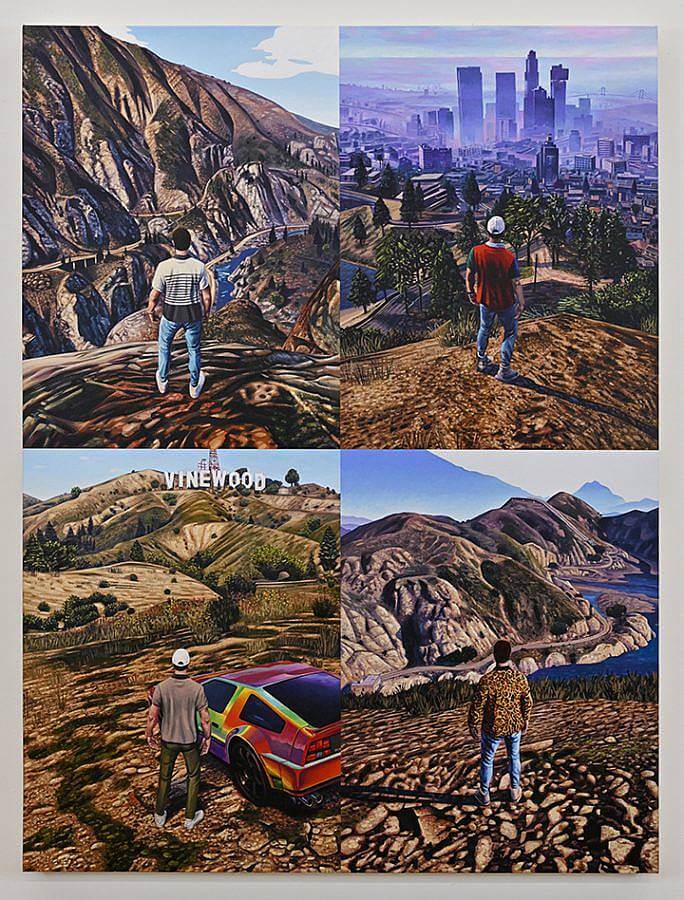

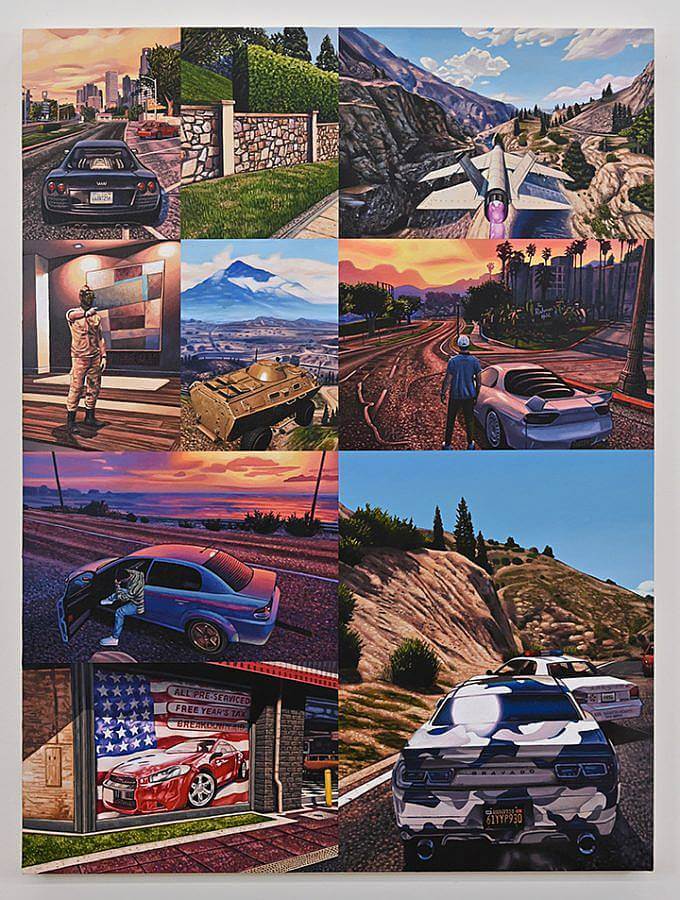

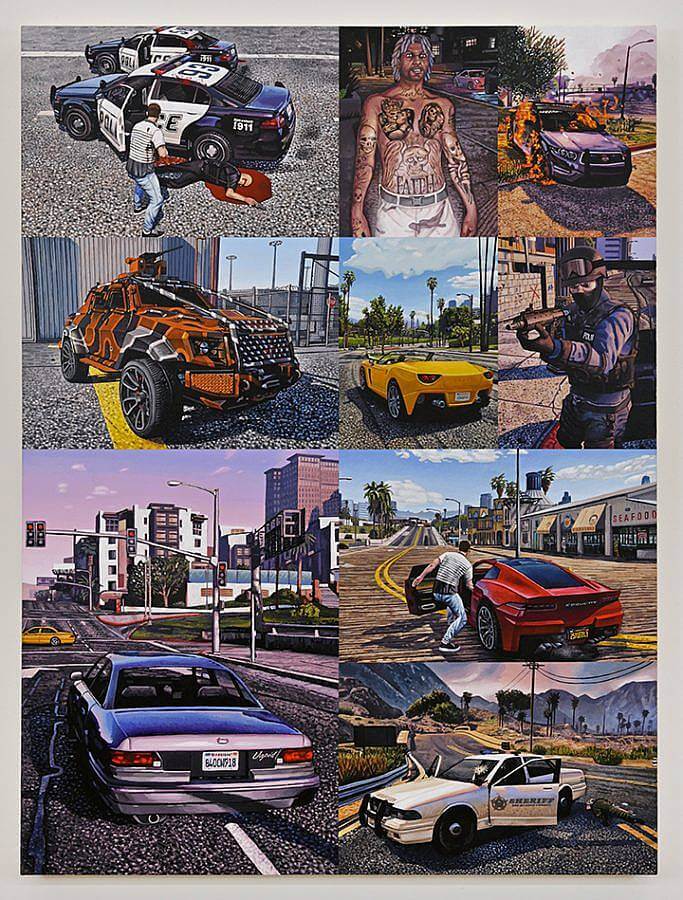

This exhibition features paintings informed by the 2013 video game Grand Theft Auto V (and Grand Theft Auto Online). I use my own avatar, wardrobe, and personalized cars to navigate this virtual world. Exploding police cars, driving off cliffs, and interacting with other players’ avatars becomes the painted, quasi-autobiographical subject matter. “Re_Spawn” refers to the constant cycle of death and rebirth in GTA, which takes place in an alternate reality Los Angeles. To play Grand Theft Auto, is to immerse oneself in an uncanny mirror world. The imagery in the paintings directly reference the people, places, and things in LA, but through the uncanny double filter of reconstructing this place in polygons and pixels, and then redescribed in the medium of painting, further complicating the ever-growing slipperiness between different realities. The exhibition also features a site-specific hand-painted floor. The floor is based on a virtual surface texture of rocks from the video game. The surface texture image is repeated in painting 42 times to create a more complex tiled image, more like a pattern, tessellation, or stereogram. When video game designers make a virtual world, they do not need to construct every pebble or blade of grass from scratch, they can simply render one small area or rocks or grass, and then tile that image to create a (relatively) seamless environment. My painting this image 42 times is a sort of exaggeration of this programming gesture. Viewers walk on this painting to view the rest of the paintings. I like that viewers are entering the painted space in the same way players might enter the virtual space- they are immersed in it.

How did you gravitate toward video game and television iconography?

In my art education at UC Santa Cruz and UC Davis in California, I gave myself permission to experiment with a lot of different styles and subject matters. I thought of it like if you are a guitarist, don’t just play your favorite songs, but also plays songs and genres of music that are challenging or confusing to you, this will probably help you to understand what another maker was feeling or thinking when they made their work, but that you would also have different tools in your tool belt to use when you needed them. One of the artistic movements that interested me in art history classes was Pop Art. That Roy Lictenstein could set his easel up at a comic strip, or that Andy Warhol might create from something he saw at the grocery store. Wayne Thiebaud (who didn’t consider himself a pop artist) was constantly looking in his direct vicinity for subject matter (People, places, things), he wanted to record his experience in a time and place. I saw this impetus stretching back through art history, but particularly with the paintings Monet made of train stations- something new, ugly, industrial, and unlike what had been captured in paint on canvas previously, but a more truthful representation of that time and place than a more classical subject. In many ways, this is what video games or the notion of “screen time” in general are for me. What percentage of our lives are experienced through a digital rectangle of some sort? If painting is “a sum of human consciousness” like Wayne Thiebaud so eloquently states, I feel computer generated imagery should occupy considerable space in what human beings in the 21st century choose to paint.

What is your relationship to GTA, specifically, and what made you drawn to this for much of your work?

I first started playing GTA III when it came out in 2001- I was 14 years old. I was immediately drawn to the freedom of the game- yes there were missions, and ways for your player to make money, but because of the size of the map, and the format of free time in between missions, I found myself (like most) simply exploring, going on joy rides, trying to find new parts of the map I hadn’t discovered yet. This was a pivotal game in the “open world” genre where players have a sandbox to play and make their own games within the game. Along with customization in later games, there was something that felt more creative than other games which were more on the rails of a predetermined track. I am particularly interested in GTA as a painting subject because of how closely it mirrors the world we already know. This game is not sci-fi or fantasy, there is nothing supernatural, simply a representation of present day Los Angeles. Here, I am interested in painting a representation of a representation. I think there is a familiarity in that which adds to the uncanny. I could go to LA to make plein air paintings, but there is something that keeps drawing me back to using this video game as an intermediary for experiencing nature, culture, and myself.

Can you talk about the way that you approach repetition and constructing grids in your paintings?

Repetition has been a cornerstone of my painting practice for the last decade. To repeat an image now is so effortless, Xerox machines have been available to the consumer for decades, and software like photoshop means possibilities for image manipulation are vast. To paint the same image twice (or more) is a little bit more complicated. Paintings are image/objects made by a human hand, they aren’t jpegs (or at least that’s how I define it). Every brushstroke is like a fingerprint- each one is unique. I like the idea that when I use repetition in a painting, from a distance it might look like an image which was produced by a machine, but viewed more intimately, the object presents itself as a more clumsy hand made thing. I have found that viewers take some satisfaction in looking at the same image painted multiple times, and find the micro differences between them. I do too. When painting the same image multiple times, I usually paint all the images simultaneously. This means one brushstroke replicated over and over from the upper left to the lower right. Each image develops in sync with the others. I have found this process to be incredibly meditative. It’s almost like saying the same word over and over again until you forget what it means. This kind of painting is almost like “busy work”, there is more sweat in the work of execution than in strategizing, conceptualizing, or thinking. Oddly enough, the current show at The Hole “Re_Spawn” uses very little repetition except the hand painted floor. I gave myself the assignment to make a series of paintings that did not use repetition for the first time in about 10 years. This allowed me to focus more on the variety of actions, people, places, and things within that virtual world. So I kept the grid structure of the composition, but instead of the same image repeated, it was a variety of images. What’s really interesting, is that about halfway through the series, I sort of returned to repetition in a roundabout way- the images in a painting became more and more closely related to one another, like sequenced images in an animation- the same car flying through the air at different angles. This creates a sort of more lively improvised rhythm (to use more music metaphors) rather than the more metronomic rhythm of the repeated paintings.

What insight have you gained from being a painter married to another painter?

I am married to the incredible painter Kristen Sanders. In a sense, we are each other’s captive audiences in the studio. There is so much exchange of ideas and critique in our respective studio practices. Oftentimes we will ask each other for feedback on a work in progress, or an idea for a work before we even start it. Many times we find ourselves giving unsolicited advice on a work in progress- what a treat! To have community as an artist is so important. It was easy to find that in school sharing a studio with so many exciting artists, but that collaborative energy can be more difficult to sustain at different points in your practice. In addition to Kristen, I am lucky to have such a supportive group of friends and colleagues too, it always feels like we give back what we take from each other in terms of feedback and generosity. But the level of access with a partner is so much different. For example, every night when I am brushing my teeth, getting ready for bed, I walk into Kristen’s dark studio and turn on the lights for a minute to see what she is making. I can’t do that with anyone else. It’s been fun to watch the ideas in our parallel practices come together and overlap, then drift apart again. There is so much exchange that we probably are unconscious of it most of the time.

A lot of your work is very labor intensive. What does that process and headspace look like?

I feel so fortunate that I have the privilege to spend most of my time creating. My mom was a special education teacher and now works as staff at a university. My dad is an accountant. I am the first in my family to have this sort of luxurious lifestyle where I get to think up ideas, and then execute them with my hands, literally making what I want to see in this world. It’s hard not to have some guilt around this opportunity, so I really try to treat my painting practice like a job. You come into work, you work, you leave. You do it again tomorrow. There are no “outs”. I don’t subscribe to feeling uninspired, I just work. I used to be a competitive swimmer, and there was practice every day, and it was usually hard or boring, but not going to practice because you didn’t feel like it wasn’t really an option. I really try to hold myself to that standard as an artist too. I do as much as I can to avoid that blank canvas anxiety or writer’s block experience. I tend to pick up the new piece where I left off with the last piece, and start it right away. I tend to work harder, not smarter. Introducing repetition in my work around 2011 or 2012 was maybe strategic in this way- multiple painted images feels more like an assembly line in a factory, than an expressive gesture. There was always so much to do, there was no sense in sitting around thinking about it, just put your head down and do it, like a swimming workout.

This is a tough one as movies are a big part of what I consume. I think one movie I keep returning to is Starship Troopers (1997) directed by Paul Verhoeven. On the surface, the movie is a sci-fi action flick with humans on earth being called to fight an intergalactic war against giant arachnids. But the film is also a sort of pastiche of fascist and military propaganda, complete with commercials to join the fight, and do your part, and kill the enemy. The more you watch the film the more you realize humans in this context are the invaders, the colonists, the genociders, and they are the instigators to unjustly attack this desert insect culture far away. There are a lot of references to history, and I find a lot of critique of the US foreign policy, and colonialism in general. Smart flick packaged as a dumb sci-fi movie! 10/10

Interview conducted by Sam Dybeck and Ben Herbert.