Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I am a silly loving person who grew up in a house of many many children. Being surrounded by so many personalities cultivated my love of genuinely learning from people, sharing feelings, and spending time getting to know others. Beyond my interest in communication as an art form, I am also a person that loves to work with my hands. I’m a sculptor and installation artist who has worked in construction. These days, if I’m not working on podcast or documentary pieces, I’m creating spaces for community reflection and one-on-one conversations centering challenging topics that feel relevant.

What initially interested you in themes of communication?

I grew up Catholic, with shame being a major component of daily living. That meant a lot was kept hush-hush which often led to toxic and even dangerous situations, especially for kids. As a reaction, the moment I opened up, I never wanted to go back. I’ve since used my practice as a way for others to feel safe being vulnerable, being messy, and maybe most importantly, for people to feel safe being wrong and open to learning from others.

At this moment in our country’s history, it feels like we need a lot more communication, a lot more nuance, and a lot more individuality– individuality that is celebrated rather than feared. To me, communication is pushing past fear to seek understanding and to potentially find common ground.

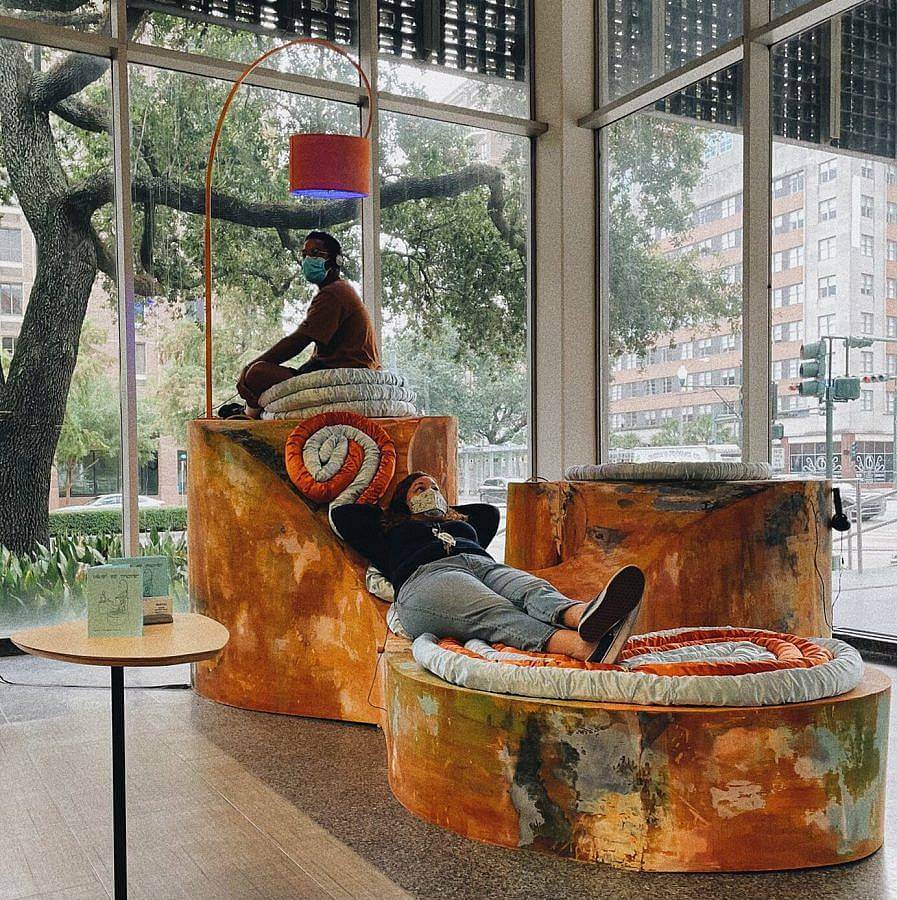

Your installations, although centered mostly around audiovisual elements, often feature large colorful objects and furniture pieces for the audience to interact with. Describe the process of making these pieces and the purpose they serve in your installations.

So much of the visual elements from my exhibitions come from dreams that I interpret or from projects that I’ve made previously. Years ago, I collected trash off the street, turned that into a collage, the collage into paintings, the paintings into sculptures, and the sculptures into large-scale installations. The shapes stay with me and become more and more abstracted, steeped in a personal history of reworking.

The sculptural seating elements I make serve to seduce and transport. I want people to walk by them and say, “I want to sit here. I want to be here. I want to get deep in my thoughts here.” If that happens, people who otherwise wouldn’t engage might be willing to have the challenging conversations presented by my installations.

Your most recent exhibitions, Morir es Vivir and Vivir Es Morir, are currently on view at the New Orleans Museum of Art and the New Orleans Public Library. What have been the main differences between working with these two varieties of institutions and how has this dual experience shaped your outlook on the future of museums?

In order to answer this question I need to explain the exhibitions a bit. Participants sat down with me for audio recorded conversations. We talked about death and rebirth, and part of that consisted of literally grieving the moments of this past year and looking forward. We also thought abstractly– “What ideas, beliefs, policies, or institutions need to die for us to thrive?” These conversations were had at the New Orleans Museum of Art, so naturally answers often reflected the place we were sitting in.

The big difference between working with the library and the museum was censorship. The museum would not allow any critique of The Helis Foundation, which is an oil and gas company. The Helis Foundation attempts to gaslight the city into forgetting that fact by putting their name on a lot of arts related things in New Orleans such as galleries at the NOMA, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, a sponsored curatorial position at the CAC, etc. Can you imagine being the Helis Foundation Curator of Contemporary Art? Anyway, of course the museum’s conservative director and curators challenged me on including many things- comments about sex, time policing, and basically anything not appropriate for a toddler to hear.

The New Orleans Public Library is dreamy to work with because it is a free and accessible location that feels quiet and reflective in addition to being set up to support New Orleanians with resources like free Wifi or help signing up for FEMA assistance. The library was also staunchly against the censorship of the art work and because of that I was able to amplify the message the museum wanted to keep quiet. The piece in library has three channels- the first is the uncensored work that was intended to be in the museum. The second channel has the words the curators tried to have me remove that I fought for and was able to include. The third has the words that were banned completely, regardless of my protest:

“At this institution[the New Orleans Museum of Art], there’s times when you can be inside air conditioning in Summer, and it’s sponsored by the Helis Foundation. So the people who are bringing global warming to you, are also sponsoring you being inside air conditioning, so you won’t actually think about the thing they’re bringing.”

When I think about the future of museums, answers from participants strike a cord– a need for the art and artists represented at the museum to reflect the community that it serves, free admission, the creation of community advisory boards, a relinquishing of power from administration to community, a deeper understanding of what the art represents to different people, how the work came to be acquired, and who it benefits or harms. Without museums embracing these kinds of concerns, I don’t believe they can be relevant and until they refuse oil branding within them, they will continue to be beholden to Helis, Shell, BP, etc and therefore equally guilty in normalizing devastating social and environmental disasters.

Both Morir es Vivir and Vivir es Morir ask the question “What must die and what should be reborn, reimagined, or resolved to go on living?”. What is your current answer?

Oh Lord! What must die? The role reversal! How dare you!

But for real…beyond death to all the -isms and -phobias that are the root of our violent system, I’d say– replace control with support, flow like water, live as one with the planet, and death to hierarchy.

What responsibilities do you have when presenting the experiences or stories of another?

I feel an immense amount of responsibility! My biggest fear is that one person or one line will be taken out of context. It’s the reason I’ve yet to release an archive of the most challenging conversations we’ve had outside of exhibition viewings. Beyond that, I feel a responsibility to show people as complex. For example, no one is solely a perpetrator or a victim – we all have the capacity to be both and everything in between. I feel a responsibility to communicate not just the facts, but also the feelings and emotions of each story or experience. My first question tends to be, “What do you want people to know?” or “What do you want people to take away knowing or feeling after witnessing this piece?” My last question is always, “Is there anything we didn’t touch upon or get into that you want to address before we end our talk?” Getting a full picture is as important as getting the emotion right.

What are some spaces outside of the studio that you find to be fruitful for your practice?

I often find myself seeking out all situations that feel new and uncomfortable. One of the reasons I love living in New Orleans is because so often I find myself having new experiences here. In the span of 24 hours, I can be feeding goats under the bridge in the morning, sitting in a circle of Mardi Gras Indians sipping on beers and beading by midday, checking out a masochistic punk clown show in the evening, and having a nightcap at the not-so-secret vampire bar. I grow the most when I’m learning from other people’s lives, minds, and interpretations and I am grateful when that spills over into my work.

How does your process as an interviewer change under different circumstances?

I used to feel a pressure to approach my work strictly as an interviewer—trying to find a truth. But then I’d watch people struggling with an answer, searching for the right words, or even trying to make sense of a situation. Those moments are telling and interesting for an audience, but can also feel uncomfortable or even exploitative. I always want to participate more than an interview allows, in order to lend an understanding ear and try to weed through struggles together. Nowadays, I’ve altered my practice to embrace those inclinations. I’ll go off record for a while, and sit with participants trying to figure out stuff together. I still help friends with their personal projects if they need an interview, or I’ll do a low-stakes side-hustle as an interviewer for money. But I’m excited to be seeing my personal practice as more conversational and reciprocal than an interview allows.

What are you reading right now?

Artwash- Big Oil and the Arts by Mel Evans, Hans Haacke: All Connected, Black Futures by Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew, and an essay by Brett Story called How Does it End.

What upcoming projects are you most excited about?

I am currently working to create an installation pop-up around New Orleans featuring Nonstop, a short documentary I made in collaboration with Zac Manuel chronicling life on the bus and transit system here in New Orleans during the pandemic. I wouldn’t say I’m excited to present this new work, but I am wildly motivated because Valerie Jefferson, the Amalgamated Transit Union President, was just fired after advocating for her fellow bus operators and I hope to use this work to apply pressure to get her reinstated by the Regional Transit Authority.

This month I’ll also be working with some of the kids I used to work with when I worked in education. I am beyond thrilled. They are brilliant, funny, wild, and so honest. I plan to ask them all the questions related to reimagining our future that I’ve been asking adults and I imagine their answers will be even more visionary.

Interview composed and edited by Ruby Jeune Tresch.