Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

My name is Kevin Demery, I’m a Painter/Sculptor that comes from a poetry/theater background. I make work surrounding trauma and impoverishment, both physically and spiritually, in the African American community. More specifically, I have been making work around racial trauma in children. This melange of crafts has created room for me to think about myself as an artist who responds rather than dictates. I have my context tell me what to make, and the autographic mark of the work is hopefully the content.

How did your interest in art begin?

I have an uncle who has been painting since the late 1970s. His work would decorate the houses of all my family member’s homes. Because of him, I began to take art seriously because I could see the impact that it leaves. He does work that is much different than mine. Before COVID-19, he was commissioned to do a piece for the Warrior’s basketball team.

Can you talk about the significance of power lines in your recent series?

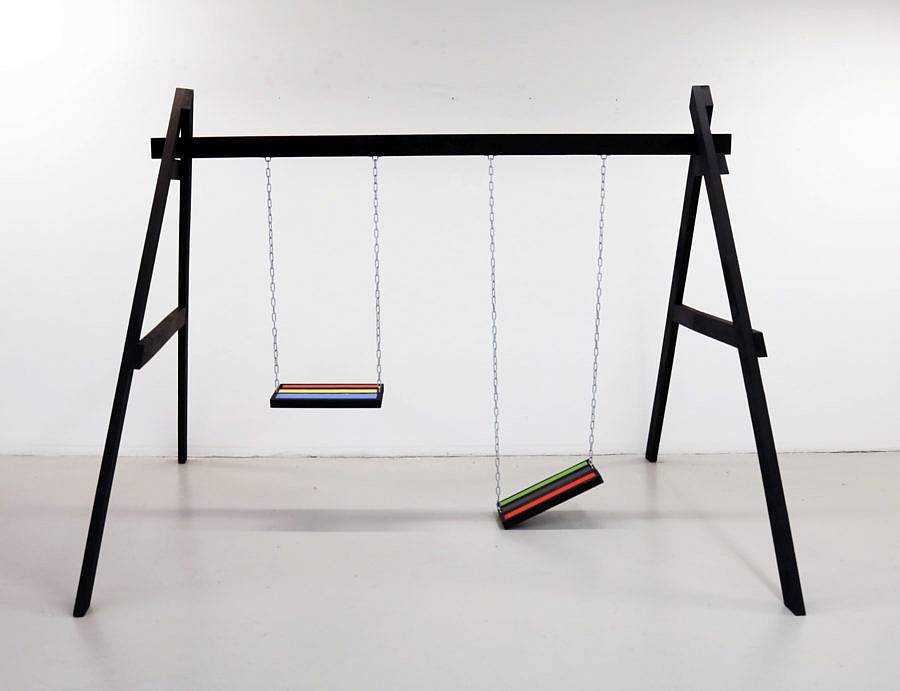

Power Lines was a way to think of the repercussions of childhood trauma in an abstract way. For me, racial and geopolitical issues plagued my youth. The use of the term power lines is to refers to the practice of hanging shoes on electrical lines within my community of Oakland, CA. I think in some ways, there are always lines of power drawn between you and what you want/ need in life. Mine have been more mental road blocks due to trauma, and that’s what the series was about to a degree.

-

Power Lines, 2017 | 40”x 51”

How has living in Chicago affected your work?

I remember walking down state street in the mid-afternoon when it was gloomy outside, and I noticed a police barricade. I immediately felt uneasy seeing this. Coming from Oakland, I hadn’t seen this object unless something violent had occurred. The thought never crossed my mind that it was for parades or something festive. I love the allegory of that, thinking something terrible is coming, and it might just be a parade. I believe Chicago did that for me it gives me a dual meaning or a way of looking at myself and all the work I do as an archive of thoughts and revelations.

What role does color play in your work?

The color used to be a non-factor if you can believe it. I got to this place with color, where it now represents youth and vibrant celebration. I think of deep purples and bright blues like chalk hitting the pavement after rainfall or paint chipping off a wall covered with layers of graffiti. It is all about letting my memory imbue the color with a more profound sense of purpose that the viewer may or may not see.

-

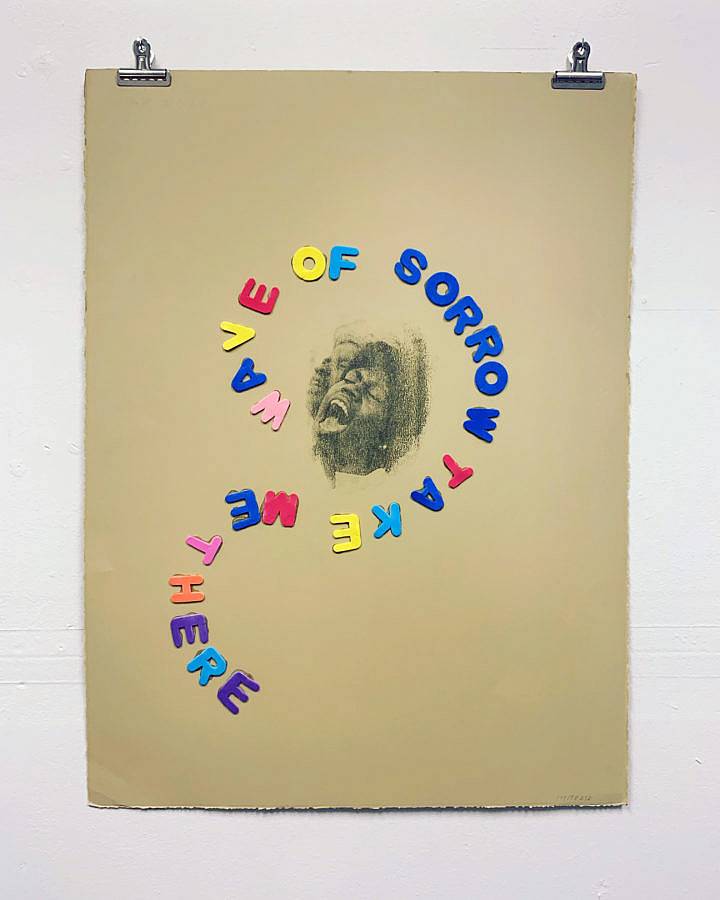

Battle Hymn

-

Wave of Sorrow

What inspired your decision to use sound in your solo exhibition, Power Lines?

It’s a bit of a story but here’s the short version:

I made the wind chimes at an exciting point in my life. I was at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, dead broke, and to some degree, quite depressed. I hadn’t made anything that I felt was good, and I was spending most of my mornings in bed looking up at the ceiling and scrolling through Instagram, looking at Soundcloud rappers. I borrowed a projector from the residency and started doing bigger versions of the head shape of George Stinney Jr., from there I cut conduit pipes from a bunch that was leftover from the then residency shop manager. It was always my plan to make a wind chime, but the decision to add it to the show was more about having this object that was supposed to be a silhouette of person make a sound. In some ways, I think at that time in my life path, I felt a bit like a stagnant object, and I wanted to make some noise, and it did that for me.

Ropes, chains, and currency are among some of the recurring objects used in your practice. Can you talk about what draws you to these objects?

Poverty. I can say that with certainty. I am finally leaving poverty, but for many years of my life, I felt restricted, and it was one of the major causes of that. I think you’re usually a slave to something in life, and most people are slaves to their wallets by sheer means of survival. I guess being a descendant of slaves and historically disenfranchised people have magnified that feeling to be drawn to the objects for votive reasons.

-

I Heard God Laughing, 2018

What is the last exhibition you went to that stuck out to you?

I went to David Hammon’s solo show at Hauser and Wirth LA. He had a work where he stacked a bunch of boxes that had the phrase “The Peoples Republic of Harlem” on them. They were all saran wrapped on top of a pallet. I loved that work because it made me realize that we were two Black people from different eras. I don’t remember Harlem being a Black place when I was there in 2015. It feels like that part of history he was referring to is gone now.

Can you tell us about your making process?

It usually is long periods of making and then significant pauses. I am shifting this nowadays, but for the most part, I will research an idea and think over the feelings it brings me. This could be a month or two for a body of work, and then I make a lot of the objects I envision, and it tends to be that out of twenty objects I make about five good ones.

-

Things Fall Apart, 2018 | 84’’ x 96’’

What are you reading right now?

I’ve been reading this book called The Delectable Negro, about human consumption and homoeroticism in US slave culture. To clarify by slave culture, they mean chattel slavery of Africans, and it primarily deals with North America though it references the Caribbean too.

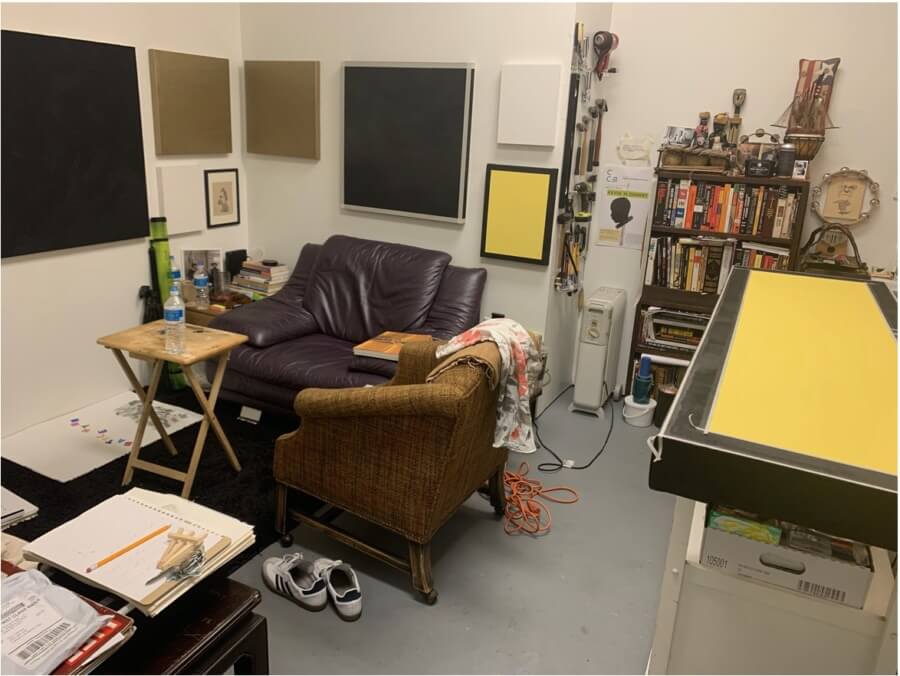

Describe your current studio or workspace. (Please provide a photo of it if you have one)

My studio makes me happy. It’s a storefront studio in Berkley, CA. I’ve been living in the bay area and will be here for the foreseeable future. It’s cozy and somewhat small but feels like home.