Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

My name is Fawn Krieger. I was named after a lake community populated with many deer, and my surname – which in German means “warrior” – originates from the city of Żyrardów, in Poland, where my paternal family lived before emigrating to the United States in the early 20th century in search of refuge from persecution. I live in New York City, and spend most of my time making art, teaching, and working for the Keith Haring Foundation, where I am program director. I am very interested in anthropology, sociology, evolutionary genetics, and in the way evolution and revolution intertwine. I think about where I live not just as a place, but also in time. I learned today that I have type O blood, which is 2.5 millions years old. What does it mean to have Paleolithic blood pulsing in the Anthropocene?

Describe the inception of your ongoing body of work, Experiments in Resistance. How do you view your current exhibition, Rebus Principle, at SE Cooper Contemporary as a continuation of this series?

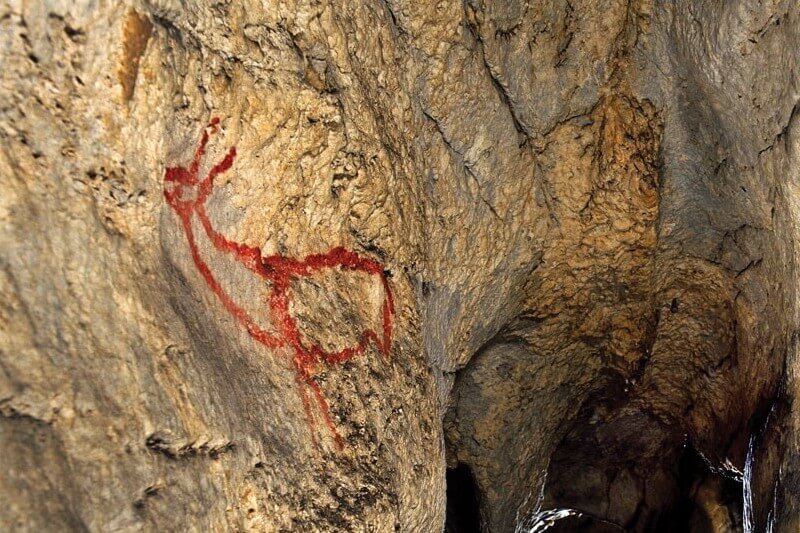

In early 2017, I began a series that would span the next four years, the Trump years. The work, entitled Experiments in Resistance, set out to ask what resistance looks like as it emerges from the body, my body, before it is socialized and politicized. I worked with concrete and clay, both materials that hold the memory of physical movement, and that have absorbed human imprints since our earliest marks left in limestone caves and footprints in evaporated river basins. As I moved through those four years, I slowly began to see the resistance shift from my body to the concrete, and as this happened, I found myself moving away from themes of refusal, displacement, and dispersal to those of fusion, convergence, and entanglement. This is where my new work begins. I’ve titled the series //, which, when spoken, is the word Caesura. It is both a visual symbol and a word, and it is defined as a pause in language.

A selection of the first 20 //s will be on view at SE Cooper Contemporary from 30 October to 5 December, 2021. The solo exhibition is called Rebus Principle. A Rebus is a picture that also stands for a sound, and the Rebus Principle is the phenomenon of a grouping of picture-sounds that converge to form a word or sentence. It is the history of how these words I’m writing here first appeared. They were once all pictures, each with their own meaning, and those pictures are still buried in our letters. An “A” is a bull’s head, turned upside down. A thing as a vessel for its own becoming.

How do you use material and process to explore larger themes outside the limitations of the studio?

It’s the other way around for me: where I explore larger themes outside the studio, and that comes into my material processes. One example is a research project I’ve been working on for the last 14 years, documenting mountains of rubble throughout Germany. The project is called First Hand. The mountains are the result of efforts to clean up the country following WWII, and were constructed from a primarily female manual labor force. Many of the mountains are overgrown and situated on the social periphery of cities, despite often standing in their physical centers. I was drawn initially to examining landscapes reshaped by women, and to studying what trauma looks like as it is transferred from the body and absorbed by earth. However, as the research progressed I became immersed in the shards of objects I found emerging from the surfaces of these mountains– old porcelain fuses and beer bottle tops, brick and mortar chunks, broken china, glass bottles. Ceramics in an expanded definition, and the materials I now work with. I see the ruin in these materials while I’m building with them.

Your work studies both material and socio-political resistance while simultaneously being engaged in a formalist dialogue. What are your opinions on the perceived neutrality often associated with formalism?

I don’t perceive formalism as neutral, and I also don’t consider my work to be formal. I make choices and take action because those choices and actions deeply mean something to me, and because they help me to understand who I am, what I come from, and the world I live in. I might edit down after making work, to clarify my voice for a given context. But I would call that a pragmatic decision, sometimes also a conceptual one, but not a formal one.

How do you consider artwork versus artifact?

I love this question, and it’s at the heart of everything for me.

When we experience visual art, particularly two and three dimensional work, it’s easy to forget that there’s multiple temporalities embedded in the work. A sculpture goes through a transformational process to be made, its contours and impressions serving as the record of that making. It is the sum of an event; it also stands before us having been made. Both are present tenses that tell two different stories of exchange, discovery, ritual, and function. Sometimes these stories converge through time or through encounter, sometimes they do not, and run in parallel dimensions forever.

Where does play come into both your process and the viewer’s experience of the work?

When I was a child, my father and I built a dollhouse together. It was sort of endless, like I was the Sarah Winchester of dollhouses. Once the structure was finished, I immersed myself in decorating, and the thing that really consumed me was making the fake food. I made lots of carbs- muffins, loaves of bread, matzo ball soup – mostly from a pasty concoction I stumbled upon of saw-dust and wood glue. A lot of it was about squishing and squeezing and poking. That wasn’t my first foré into pretending I was a chef making imaginary food – and clearly it wasn’t my last.

I think less about play and more about fantasy construction and world-making, and how to generate propositions that feel both homemade and potentially inhabitable – like a provisional utopia.

The concrete in Experiments in Resistance can often feel like a living, threatening, and all-consuming force whilst simultaneously retaining the impression of slowness. How do you reconcile your agency as the artist with the agency of the material?

Agency relies on an awareness that it is in a constant dynamic exchange with other agencies. I can’t imagine, and wouldn’t trust, a sculptural agency that perceives itself to be operating alone amongst inanimate things. I don’t seek to reconcile this dynamic, I embrace it and make that the work.

In an ideal world, how would you like viewers to engage with your pieces?

I would like audiences to engage with my work on their own terms, and within an atmosphere that is warm and also serious, and which puts the work and audience safety first. I am drawn to curiosity, rigor, ecstasy, commitment, wordlessness, compassion, generosity, and courage.

What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Dara McAnulty’s Diary of a Young Naturalist. Last night I read Fortino Editions’ The Smiling Moon, by Mauro Zanchi, which is a super compact and radical essay on the Renaissance painter, Lorenzo Lotto, and which also touches upon the idea of the rebus. I’ll be taking adrienne maree brown’s We will Not Cancel Us and George Kubler’s The Shape of Time to Portland with me. And this week’s New Yorker!

One of your upcoming residencies will be at the legendary Josef and Anni Albers Foundation! What are some of your current goals for this opportunity and how do you view your work in relation to the history and impact of Josef and Anni Albers?

I’m very excited about this opportunity!! My goal is to absorb. I’m interested in the design and structuring of learning, especially with experimental pedagogies. I’m also interested in how context and proximity alter experiences of perception and understanding, which both of the Alberses worked with in distinct ways. And along these lines, I’m interested in how patterns are created and broken or interrupted. And I mean these ideas to be symbolic of bigger systems of thinking, particularly around processes of seeing and learning. I am drawn to artists who have been fundamentally shaped by diaspora and revolution, and more personally, by the Holocaust. I work at an artist foundation, and I teach; there are few contexts like the Albers Foundation Residency, which can enable me to bring many of my concerns together for cross-pollination and study.

Tell us more about your recent collaborative series, VOLUMES, with Anna Huff Mercovich.

Anna and I have been working together for almost four years. We have a slow correspondence through objects and sound and time. It began with a conversation around making a rogue TV show where I create the sets and props and Anna works on the choreography and audio components. It has evolved into considering sculptures as central protagonists, from which narrative, sound, movement, and dialogue emerge, in contrast to the conventional theatrical canon where the props and sets are often the last components in the construction of content. The work proposes an exchange of subject/object roles, and navigates solutions to explore a materiality of time. The series inhabits test sites to create collaborative and community-driven live performance labs, from which video sequences are captured, edited, and made into autonomous vignettes that negotiate between 2D/3D/VR (virtual reality).

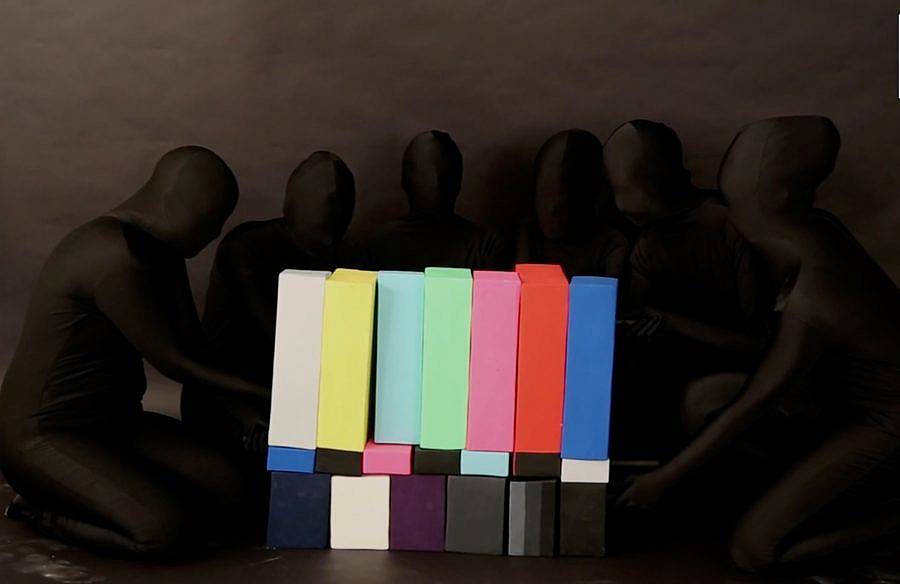

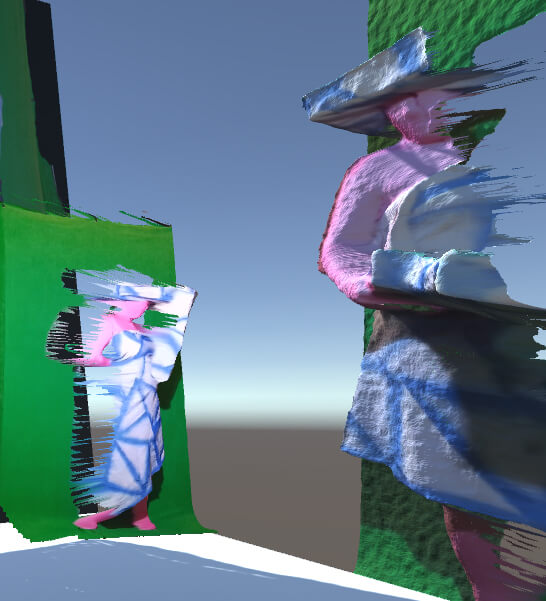

In a way it’s like we write letters to each other, but instead of it being an actual letter, I might send her some sculptures, and then she might 3D scan them and build a VR environment made of them and send that back to me. And we go from there. The first photo included here is a video still from the series’ opening sequence, and includes a sculptural version of SMPTE video test bars, which Cornell students danced with and aimed to bring back together to form variations of the standard “This is a Test” screen. The second image Anna casually sent me the other day as she was plugging herself into a 3D landscape while wearing my sculptures. Imagine getting that text! It’s a profound treasure. I really cherish our collaboration – Anna is a radiant human being who continually inspires me, and the work we do together scratches this multi-dimensional itch I would never get to on my own.

Resulting in even more points of material tension, your more recent Experiments in Resistance showcase a wider variety of glazes and surface textures than in previous iterations. What were your intentions with this slight shift in your ceramic volumes and how do you see it developing?

Yes, even though I’m still working with clay and concrete, there’s a lot of changes in the new work. The frame went away, and the concrete went from being a solid trough to a glue or binding agent. For the past year or so, I’ve been thinking about proximity, like how entities placed next to one another form a sensation or consciousness that neither can establish alone. With the tail end of my previous series, this amounted to colored forms that individually might have appeared one way, but radiated in a different way when placed beside one another. With my new work, I constructed most of the forms differently – a lot of them are cast porcelain, so they are in multiples. But then I applied different patterns to the forms, establishing distinct visual lexicons or families. Though the patterns may be similar in one grouping, there are variations between each form and its pattern, and this creates an energetic charge. Some of the patterns are loosely inspired by the field tools used at archeological sites to show scale in photographs. And a lot of the patterns take this thinking around proximity one step further, where the applied pattern negotiates the dimensions of its own volumetric form – two perspectives that must exist simultaneously, maybe not unlike the 15,000 year old deer painted on the wall of Covalanas Cave.

Tell us more about your studio and studio cats.

My studio is currently in my home. I work on messy work in my finished basement – where I am mostly – clean work in a former bedroom, and I have a woodshop, metalshop, and kiln in my garage. I’ve worked in so many other contexts outside of the studio, and around lots of people, including on-site commissions, theatre projects, residencies, schools, hotel rooms, and kitchens, and it’s made me unromantic or just practical about THE STUDIO as a site. What’s mostly magical and unique to me about the studio as a space, are the kinds of conversations that can happen there and nowhere else.

I have two cats, Emma Goldman (AKA Chkn) and Rosa Luxemburg (AKA Waffles). They are 3 years old. They are not always allowed in my basement studio because of the materials I’m using. But I regularly do thorough cleanings and they are always very excited to re-claim the space after those occasions. The other day I left my door open for a second and came back to Chkn luxuriously rolling around in the middle of my studio floor. It was a full sensory experience for her.

You’ve previously stated that you tend to pay more attention to theater and the performing arts than to work in museums and galleries. What benefit do you think this preference has on your practice?

I do pay a lot of attention to what happens in museums and galleries. But I think a lot of it has to do with my innate response to white spaces and black spaces. What they mean in society and how they each wrestle with safety, viewership, perception, community, labor, sexuality, accountability, mortality, movement, and moment in very distinct ways. I see my work equally at home in both spaces, but my ethics and interests originate in a black box. Feeling connected to two distinct institutional cultures definitely reminds me that there is not one established canon or center, and this can be both grounding and revelatory.

You’ve recorded several videos of the making of your work. Have you ever shown these alongside your physical pieces and if so, what do these videos add to the experience?

So I’ve been “fruiting” (a term my friend Wynne Greenwood proposes in place of “shooting”) video of my process of combining the fired clay and wet concrete. There is a short moment of elasticity when the cement is still fluid, before it hardens, and it’s a sort of an indescribable catastrophe during that whole moment. I’ve yet to exhibit these videos alongside the sculptural pieces, but it is something I’m thinking a lot about.

What made you want to be an artist?

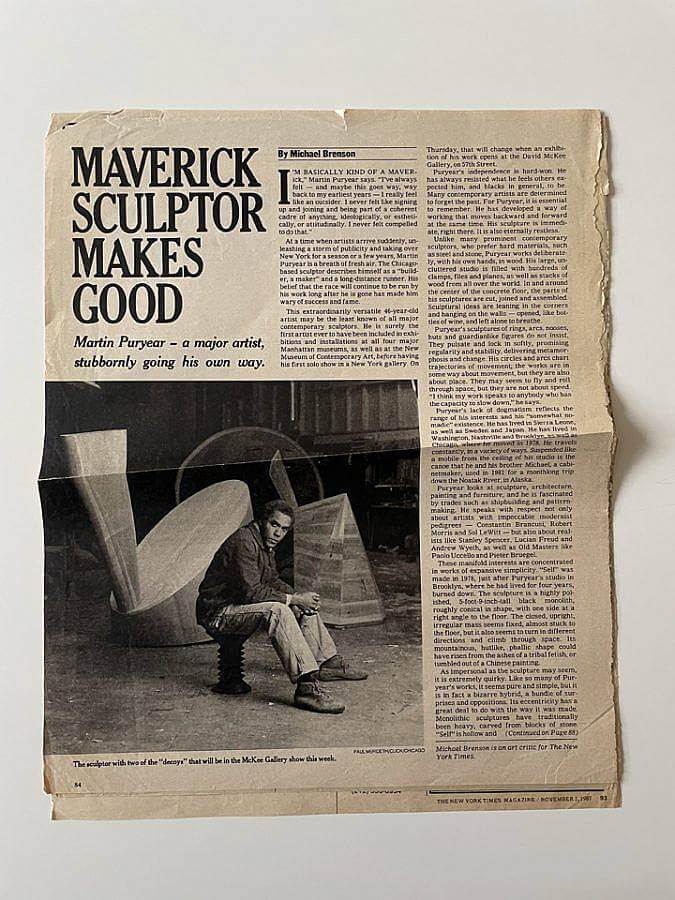

Art was the only thing I ever wanted to do as a kid– I didn’t want to play sports or study. It wasn’t just the making, it was a way of connecting to, comprehending, and constructing a reality beyond the one I saw. When I was 12 my mother showed me an article in the New York Times Magazine about the sculptor Martin Puryear, Maverick Sculptor Makes Good. The piece, written by Michael Brenson, who would later become my teacher, and then my friend, prompted my first realization that I could live as a sculptor, as in, be alive and make things that live in the world with me. Before that I only knew of dead, white, mostly straight male artists. I related to the way Martin inhabited his body and how this entered his work, and his global cognizance of craft languages and traditions. I would clip that piece out, and store it in my closet for the remainder of my childhood, and would take it to college with me and then into my first studio. It’s with me today as I write this, on the shelf behind me. That article was the beginning of many decisions to come, on being an artist, and unfolding what that means and why it matters to me, not just as a maker, but as a daughter, a partner, a parent, a friend, a teacher, a citizen. It’s not a role of production, it’s a position of being. And it’s also not a decision I made once, but a commitment constantly challenged and renewed. Brenson’s Puryear article showed me at the age of 12, that I can make a life I believe in, and I could survive there.

Interview composed by Ruby Jeune Tresch.

Special thank you to Derek Franklin of SE Cooper Contemporary.

All images courtesy of the artist and SE Cooper Contemporary, unless otherwise noted.

Fawn Krieger: Rebus Principle is on view 30 October to 5 December 2021 at SE Cooper Contemporary, 6901 SE 110th Avenue, Portland, OR 97266. For more info: info@secoopercontemporary.com