First of all, how are you doing during this pandemic?

My focus primarily has been on maintaining my stress levels (especially in the beginning) as to not make myself unbearable while living in close quarters with my family. I didn’t want to take my stresses out on my kids, or with my wife- so that’s been my focus. I’ve dealt with that through a routine- getting up at the same time, dressing, you know just trying to have some semblance of regularity.

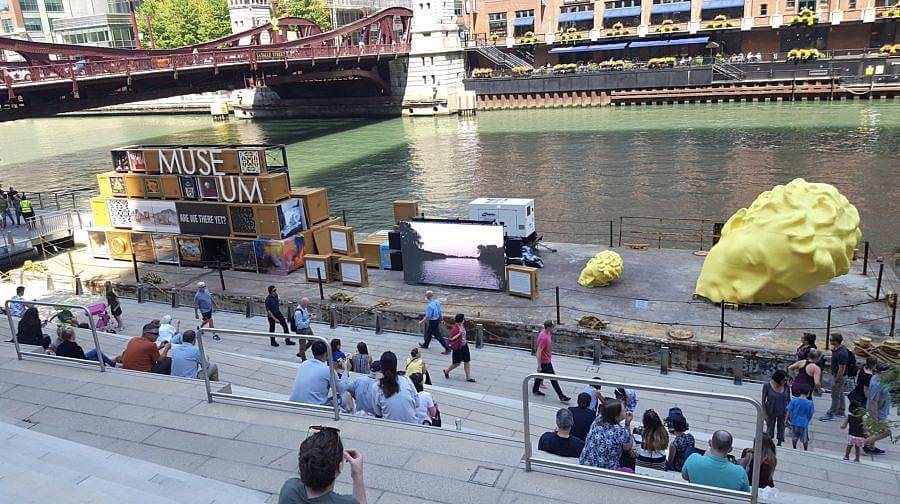

With my projects- all my shows have been postponed, which I wasn’t too upset about because I just didn’t feel like I was in the right mind space or spirit to do the things anyways. You know, who wants to be the first show out of a pandemic? I don’t know how we’re going to engage and when we come out of this, socially. So I was fine with that. Project-wise, with my Floating Museum project and my collaborative project, we weren’t planning on doing anything this summer in public anyway, so it didn’t impact those things.

I teach at UIC , and at school we’re kind of finishing up this week (May 6th). I do look forward to actually getting back into my studio, cleaning up some stuff because my ceiling fell in. Anyways I’m looking forward to that, I’m looking forward to cleaning up my studio and making some new work.

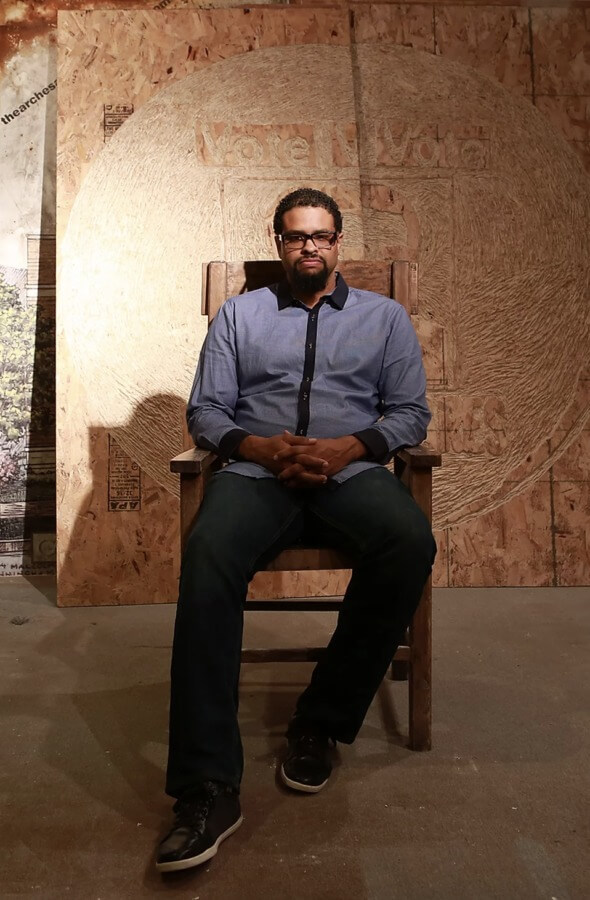

Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

Yeah, so, I’m an artist – I always call myself an artist or a sculptor first as to not, you know, deflate the value of that. I wear a lot of different hats, but they all come through my creativity. When I see myself, I see myself as a sculptor first, but I also have a practice of working collaboratively in more socially engaged and community based processes, which I like to think at this point in my career are separate trajectories that I try to frame in such way.

What are some recent, upcoming, or current projects you’re working on? Are you working on anything right now?

Yeah, the thing that was recently postponed was a solo show that was planned for this summer at the Hyde Park Art Center and the South Side Community Art Center. It was a whole, kind of making work based on the space I used to manage and run in Bronzeville , and then had a show there, and the making being an event. And then that thing being moved to the Hyde Park Art Center for an exhibition afterwards. The whole idea was connecting these two institutions that I’m very fond of, to give more concrete connections in hoping that other things will come out of that. So there’s the work, then there’s the relationships that are the sustainable things left. That’s all been pushed back to next year.

Also, with my Floating Museum collective, we’re working towards a big project in Copenhagen that we’ve been working on for the past year, but that isn’t until 2021. So we were primarily going to spend the summer building support, artist selections, things like that, on both sides of the water. So there’s no reason why that can’t happen, but we still have to take into consideration, really everything now.

You’ve held various administrative positions in the Chicago art world, so what made you decide to focus on your studio practice full time and how does your administrative and curatorial work influence your art practice?

So, to be clear, I did step away to do my studio practice full time, and I want to say, maybe in the last two years, I did step back into academia because I was a visiting artist and I enjoy teaching, it’s something that is satisfying. But what I did step away from was, my position as the associate director of UIC art and art history for about two years, and you know, I wasn’t able to do a couple of things at the same time, so it just made sense for me to step away and as I say “make a run for it.”

Now I’m approaching coming back, not administratively, but as an instructor a little differently, I have more resources, I was able to do a lot of things that I wouldn’t have been able to do not having the space, time and support if I didn’t step away and really delve into some of those practices. Administratively, my time as an administrator of an arts non profit as in academia, it does help me to organize a little bit. But there was a moment when I was merging all that stuff into one singular thing- meaning the running of a space, is the art practice, it is the institutional critique, but now I’m looking more at separating these things, I realized in some of my other goals along the lines of relationships with galleries, sales, museums, and things like that , it gets a little murky. The collective work gets a little murky. I do need my own private space, so I can work hard at Floating Museum and Black Wall Street project which I’m working on with Amanda Williams and Rick Lowe. But I also want to work really hard in my own solo studio with shows like at the Hyde Park Art Center and things like that. So it’s just, you know, organization.

Can you tell us about your work at the South Side Community Art Center? What was your position and what were some projects you worked on?

Yeah, a lot of my current work comes out of that time. Anyone who knows my work knows that I can’t go three sentences without talking about it. I was executive director there, and prior to that, I came to the center as an artist just walking in off the street and fell in love with it. Maybe over the course of seven years, five years or so, I became executive director. First, they hired me as a curator after being a volunteer and an artist in a couple of shows. It’s kind of like walking into a church- They loved me, right away. I loved a lot of the older members, and they wanted to support my future. So, for a while, I was pretty much the staff along with everybody who was part time- but I was the first executive director. The directors in the past were more like docents and curators, so the board were the directors, they ran the space. Because of funding opportunities with grants, you can’t have a board being your director, so I was the logical choice as an acting executive director. After maybe three years of being the acting executive director and realizing there’s no director search, I was like, “Oh! Well maybe I should just like… because I’m doing all the work, so…” I don’t think I was qualified, actually, one of the qualifications was that I weld good, because I was a welder, I don’t think I could get the job now, but I learned on the job.

I thought about running the space in the same way I think about making a sculpture- doing a project. So, I built a language about running a culturally specific institution based on very specific needs. In grad school I was able to understand that “Oh, that’s not only a language for running a space, it’s also maybe a language for an art practice”- I just have to translate it a little bit. That’s why I have more museum shows than gallery shows,- I’m able to understand the non-profit space really well- the cracks, the needs- and I can kind of move those things around in a way to make really interesting things that satisfy all the stakeholders.

So given that your work inherently has an aspect of institutional critique, how has your work been institutionally received in some of the larger institutions like the MCA in Chicago?

Yeah, they love it! The misconception or misunderstanding is a lot of people think my institutional critique is about the dominant, white, large institution, and it’s really not. It’s about the small, black institution. So it’s really about attacking the little guy, In the beginning, especially, my thesis was “Demise of the South Side Community Art Center”- how to burn it down. It wasn’t about an outside thing, it was about looking inward, and understanding I’m implicated in that. So, I mean, the museums and a lot of curators love it because it’s thoughtful, it’s insightful, and wants to pick on the little guy. But I think we have to in order to strengthen those models. So like, why is a space like the South Side Community Art Center, necessary? Can it stand on its own? That’s the kind of institutional critique I was really interested in. And I’m able to do that as someone who knows all the vulnerable spots. When I had my solo show at the MCA, I did a 1/3 version of the gallery at the South Side Community Art Center and invited people to come in. It satisfied something for them. In a way, the piece thinks about value, it thinks about the undervalued and valued, so it invites people in who really don’t give a shit about the MCA and they go “Oh, okay, we’re gonna do this here.” It also brings in facilitators who have their own audiences that do not need or value this space, but maybe they value the space of the South Side Community Art Center, so it’s a power dynamic shift, and also a space to have an engaging conversation, that’s where that space is.

They loved that because that ultimately satisfies some of the things that they’re charged with, from a number of supporters, funders, and all sort of people. It’s a creative way of doing that. So, I don’t really have any problems going into those larger spaces. It’s the smaller spaces I’m more interested in, they’re delicate, and fragile and need more attention, and I also love that too.

Can you talk about your material choices? How and where do you source the building materials or sites that you work with?

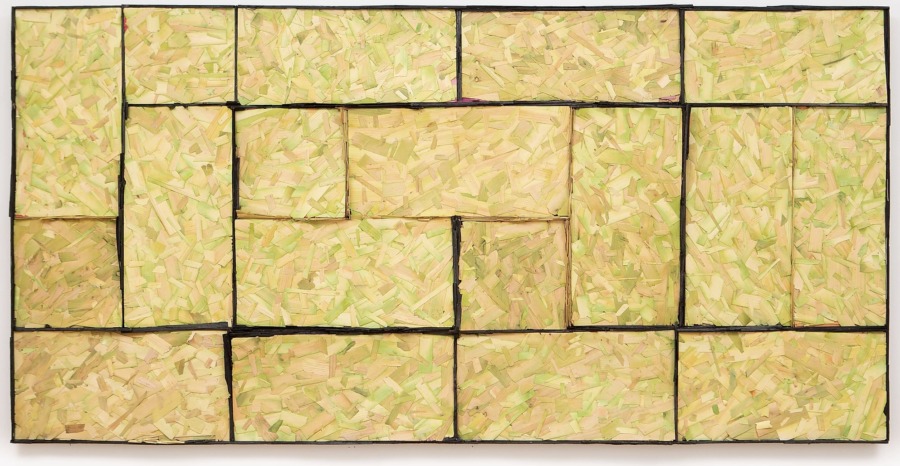

Yeah, you know I told you I was a welder, and I went to Howard University where I was the only sculpture major. So you can imagine what kind of budget comes with that, you know, there is no budget! That meant I had to learn how to scrap and make my materials out of things that were found– this is all I’ve ever known. My material choices really come out of being taught how to find value in the discarded. So that’s basically dumpster diving and remaking things. Of late, I’ve been making my own version of OSB particle board. The material and patterning itself is a reminder and a connection- OSB particle board is used to board up windows, and boarded up windows in my neighborhood and neighborhoods I work in mean something, right? , it’s a pattern that has a signifier, but that same pattern, when you put it in a place like the MCA, starts to have a conversation with an abstract painting. I always found these two things interesting, and the first phase was kind of about found objects. I find it then I PLACE it, so it’s about the placement of that thing. Then I may etch something into it. But ultimately, it’s about moving it from one space to another. The evolution of that is to actually make the OSB pattern. In one thread of my studio I’m exploring painting, so i’m making stained versions — finding 2x4s, stripping them down really thinly, like shaved meat. And re-fixing them.

Yeah, I was going to ask how you do that…

It’s a very tedious, tedious process, it’s all found material from previous projects, and mostly 2×4 studs that I find and chop into small rectangles, then I shave them really thin. So each one of those pieces, no matter how big it is, someone has taken the time to shave it and stain it with a Kool-Aid stain that I’ve concocted, and put it back together. It is about repetition, it is about being tedious, there’s more to it than it seems.

All these things are metaphors for thinking about space and people, but ultimately it looks like kind of a splatter painting, or a boarded up window. I had a show at the Cultural Center, where I boarded up one of their windows. You say “boarded up windows” and what it means to board up a window on the south side, and now you’re boarding up a government building- so what is the statement you’re making? I had two audiences coming in and some kids actually said “Oh you boarded up that window” and others said “Oh that’s a stained glass window.” And they’re both right, but for me that’s an exciting moment to be able to have an almost a painterly gesture that talks about two very different systemic and class spaces.

Your Shacks and Shanties project has a significant social and collaborative aspect to the work, so can you describe how this work came about and how it evolved over time?

It was a very interesting moment when took the lessons of a culturally specific institution and moved them into a studio practice and a public practice. This was right after grad school, I had just stepped down from SSCAC, and I had experienced a loss, like that was a real important time for me. I no longer had access to a building, and I hadn’t really taken that into consideration. I also had just finished up at UIC, it was a very hard period. My relationship to art had changed. After those experiences, everything was intellectual. I couldn’t look at art anymore without thinking of art historical connections. I couldn’t make art for the love of making art.

Shacks and Shanties initially came out of being invited by the Southside Hub of Production, which was a group that took over a church in Hyde Park. They were inviting artists in to do all kinds of crazy shit in this big ass church. Everyone was in there, Laura Schaeffer, Jon Preus, Erik Peterson, and my partner now, Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford were kind of central to organizing that, and it was great! It was amazing. So they asked me, “Hey would you be interested in doing something here?” and I was walking around the building and saw on the roof, there was this space, it was a gangway. So I was making a joke, I said “This would be dope for a treehouse, I should just build a shack up here.” I just wanted to reconnect with making just for the sake of making, like a childish thing. I just want to make something, I don’t want to think about it. So I made this shack, and the title of the piece was Sometimes you don’t need an excuse to build a shack on the roof. And I left it. and there was a whole story about working with a guy in the neighborhood who I became close with and he carried the equipment up every day. Ultimately I left it and people started moving into it, and they kept calling me asking permission and I just told them, “don’t call anymore, just do what you want to do, you don’t need permission, just do it.”

Then I realized, “Oh, there’s a value to this, there’s something about making space” This was unintentional consequence of building it on a roof and it being dilapidated that was inviting. I took those lessons and I moved them to a space that I live and a space that I work, one in South Shore, and then one in Bronzeville. Each of the shacks were teamed up with a local community, one was a community garden, the other was an advocacy group. Then, I started inviting a bunch of people. I started out with 14 and every time the audience would become participants and therefore producers, and only a handful of people actually put stuff in it. I mean it was a sculpture. I think that got washed away from the activity, but it wasn’t a building, it was a sculpture. But it was a beacon. it was just calling “here’s opportunity to do something,” which is what I was doing at the Southside community art center. I just wanted to take those lessons and bring them to spaces I cared about and people that were doing work. So that was the project.

Where are the structures now?

They’re gone, they were never intended to last long, I didn’t want to be the “Shack guy.” I’m so glad I didn’t do that because at the end of the summer, every shack, shanty, newspaper stand, people thought was mine. It was only two, but somehow, I was all over the city. It was more of a project that had a beginning and an end, it was a sweet moment. There were some interesting things that came out of that. Amanda William’s’ first public experiment of thinking about color theory happened. They colored the dirt, she went into the house and got a paint sprayer, so it was like why not? We don’t have to wait around for permission, let’s just do what we want to do. It was about not asking permission, I don’t need a museum to tell me I can’t have a museum show– which is when you get a museum show! Haha

Who would you love to collaborate with and why?

That’s a hard one! I mean normally I would say Rick Lowe, but that’s who I’m collaborating with now. Rick Lowe is someone who, if you’re working with public space, really laid the foundation for long term socially engaged art practice or community-based work even before that was a term. He’s also just a very humble individual, really understands the notion of how to work collaboratively, especially among ego centric artists, which is something I think we do share in common. It’s hard to work collaboratively with artists. Ultimately, we want to be the center. so he’s someone I’ve learned from watching over the years. Recently we’ve been working together along with Amanda Williams on a project we’ve been working called Revisiting Ideas Around Black Wall Street, and we’re building that collectively over time. It’s about solidarity and financial and cultural independence, taking lessons from the success of Black Wall Street in Oklahoma. So that’s something I’m working on now, we’ll see how that manifests. We’ve been working kind of quietly for about a year. There’s a lot of people I really, really respect out there in the world.

Interview composed by Madeline Olson