Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

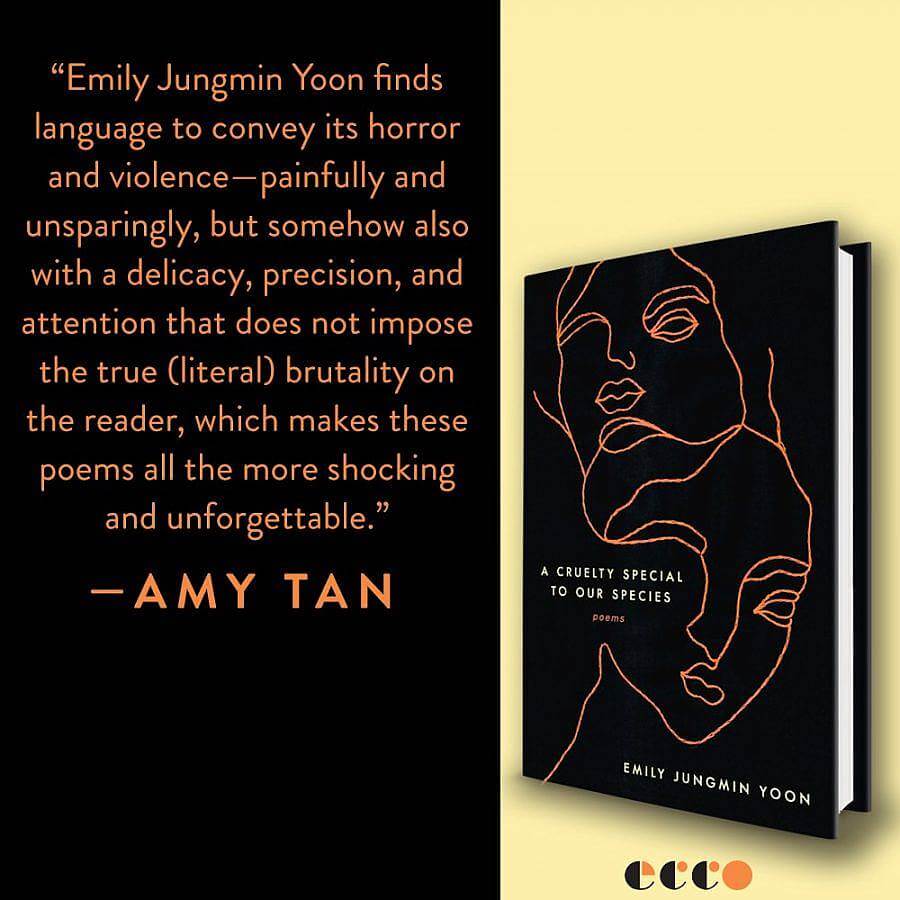

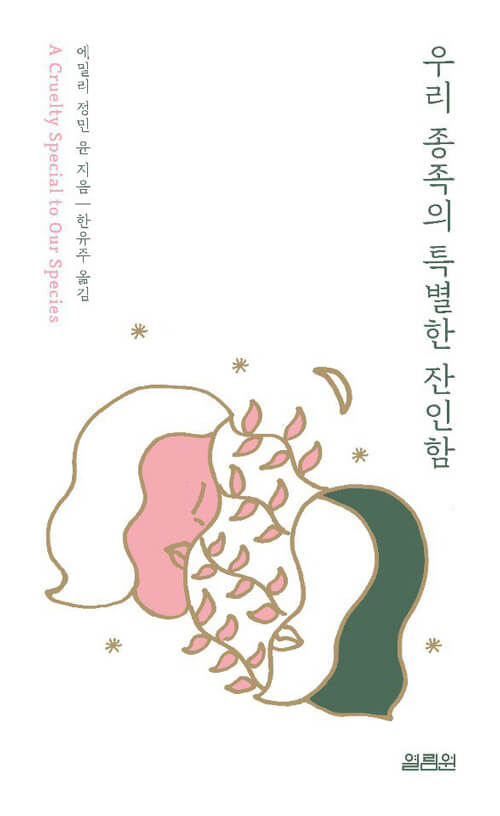

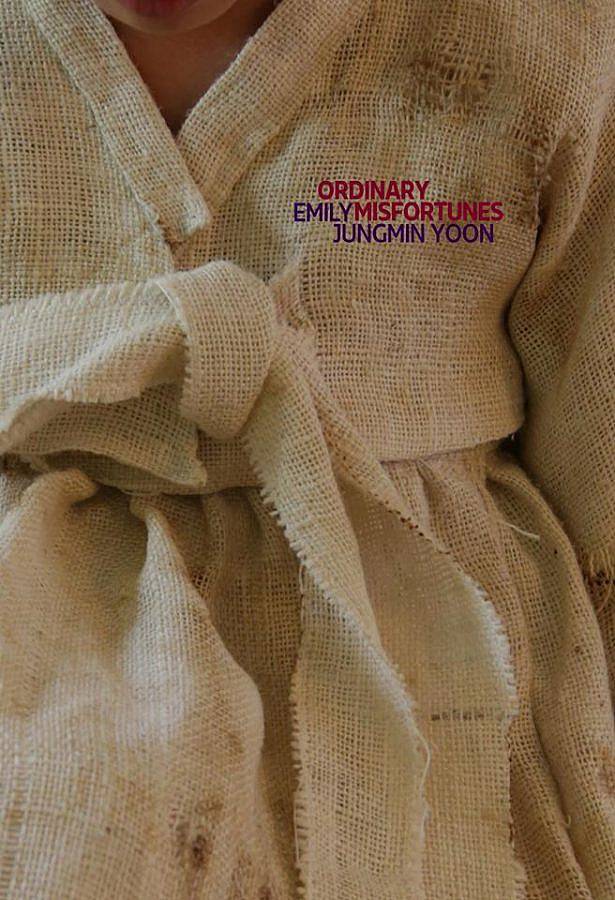

My name is Emily Jungmin Yoon. I grew up in Korea and Canada and currently live in Honolulu, HI. As a poet, I published A Cruelty Special to Our Species, a full-length collection, and Ordinary Misfortunes, a chapbook. I am the editor and translator of a chapbook anthology called Against Healing: Nine Korean Poets. I serve as the Poetry Editor for The Margins, the digital magazine of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Currently, I’m pursuing a Ph.D. in Korean literature at the University of Chicago, and am working on a Ph.D. dissertation on contemporary Korean and Korean American women’s poetry.

How did you get started as a poet, writer, and translator?

I loved writing for as long as I could remember, but I became very immersed in poetry in high school thanks to my creative writing teacher, Terence Young. He is a poet and introduced me to some living poets I had never encountered before, such as Li-Young Lee, and inspired me to continue pursuing poetry. I think I always had an interest in literary translation but was able to put it to practice in college when I spent a semester of my junior year at Seoul National University. I joined a literary translation club and we worked on a play together as a group. Then I went back to the University of Pennsylvania and took a poetry translation workshop with Taije Silverman, which proved foundational for me.

What writers or artists have influenced your practice?

Li-Young Lee was probably the first poet I became a serious fan of, back in high school. His poems taught me how to write about immigration, family, loss, and love. Now, I often turn to my Asian American peers––Kien Lam, Wo Chan, Sally Wen Mao, Paul Tran, Monica Sok, Fatimah Asghar, Sumita Chakraborty, Franny Choi, and EJ Koh to name a new—as well as some older poets like Cathy Park Hong and Don Mee Choi. There are so many other poets whose works are important to me, but it’s always particularly very energizing for me to read such heterogeneity within Asian American poetry. As teachers, Kimiko Hahn, Charles Simic, and Yusef Komunyakaa were instrumental for my writing. Kimiko gave me a sense of permission to be bold and precise, Charles taught me how to find the heart of the poem and make necessary excisions, and Yusef helped me unearth the things that were brewing under the blank space and needed to come out.

I return time and time again to your poem “Related Matters,” thinking about the way you fold our desires and the unrelenting reality of the world up against one another. Can you tell us about this poem and its topical nature?

Thank you. The poem began with that line that says there is nowhere I want to live, but I do want to live. There is nowhere because every corner of the world is touched by climate change, in addition to the incidents of human violence that are specific to each area. I also folded in the images of my mother tending to her plants that my grandmother left behind, braiding in the more immediate grief (from losing a loved one) with the seemingly more abstract dread (of climate change), occurring simultaneously during extreme weather conditions. This poem gives me a sense of respite because many people responded to it, and I don’t feel alone in these intermingled fears.

Thinking about, “A Cruelty Special to our Species,” your book of poetry grapples poignantly with race, gender, and colonial violence. How do you feel working on and publishing that book has impacted your practice?

Publishing the book made me ponder about the ethics of persona poetry, found poetry, and representation in poetry. I struggled writing the poems because it was a strenuous process to give myself permission to write poems about the Japanese Imperial Army’s “comfort women,” since I did not live the women’s experiences myself. I feel gratitude and joy when readers tell me that they became aware of the women’s history through my book. I hope that they continue to learn about not only the “comfort women,” but also more generally about gender politics and women in war.

Can you talk about how your experience as a Korean American woman impacts your writing?

I am actually Korean Canadian, though I’ve lived in the US for more than 10 years at this point. My ethnic identity and life between the US and Korea permeate my work, of course, the same way social identity informs every writer’s work, but I do think about how my writing is perceived in the US and Korean contexts. I assume a “marginal” position in both; in the US, as a Korean, and in Korea, as a US-based person writing mostly in English. But as Kim Hyesoon said, the marginal position is a creatively fertile ground, because it is where “everything shifts.” In such a position, you have the desire and perspective to shake centralized literary conditions and tendencies to generate new forms and narratives.

How is your current experience at the University of Chicago impacting your practice?

Being a Ph.D. candidate and deeply engaging in scholarship helped me more fully and clearly contextualize my own poetic practice within the larger lineage of Asian American as well as Korean poets. Researching feminist theories and texts also inspired me to take some of the lessons into my own writing and put it into conversation with critical developments. Being a Ph.D. candidate also reminds me of how important it is to compartmentalize and use my time wisely. I need to decide in advance when and how to devote my time to writing poetry. In my MFA program, it felt like most of what I did was joyfully read and write poetry, which is of course work too, but the demands of an academic doctoral program are incredibly different and time-consuming.

What are you working on right now?

I’m mostly working on my aforementioned doctoral dissertation. This takes up most of my time, but I am also writing poems here and there to put in my second poetry manuscript. Also, I have a translation project: translating into English Kim Hyesoon’s book of poetic theories, called To Write as a Woman.

For you, what does it mean to write about poetry? To respond to it? Where do prose and poetry meet?

To render into poetry our visions and experiences is to choose language as the theatre of their drama. To describe or make our realities strange through a language that is distant from our everyday language, with a focused investigation into musicality, rhythm, metaphor, etc.

However, for me, at the end of the day, a poem is a story. It is just told in a different form and breath from prose. Plus, I do have a fondness for prose poetry, which pushes against genre divides. Sometimes, you see a poem that is very prosaic and a prose piece that is very poetic. For works like this, I think they become categorized according to what the author calls it, due to their own principles and aesthetic alignments.

What are you reading right now?

I am reading There Are Trans People Here by H. Melt. It is a brand-new collection of poems that honors and makes visible the lives of trans people, with tenderness as well as defiance.

Interview composed and edited by Joan Roach.