Tell us a little bit about yourself and describe your practice.

I was born in the U.K. but grew up in Athens, Greece. I then came to London at the age of 18 to study and I have mostly been here since. While in London, I studied Fine Art & History of Art at Goldsmiths (204-2017) and did an MA in Sculpture, at the RCA (2018-2020).

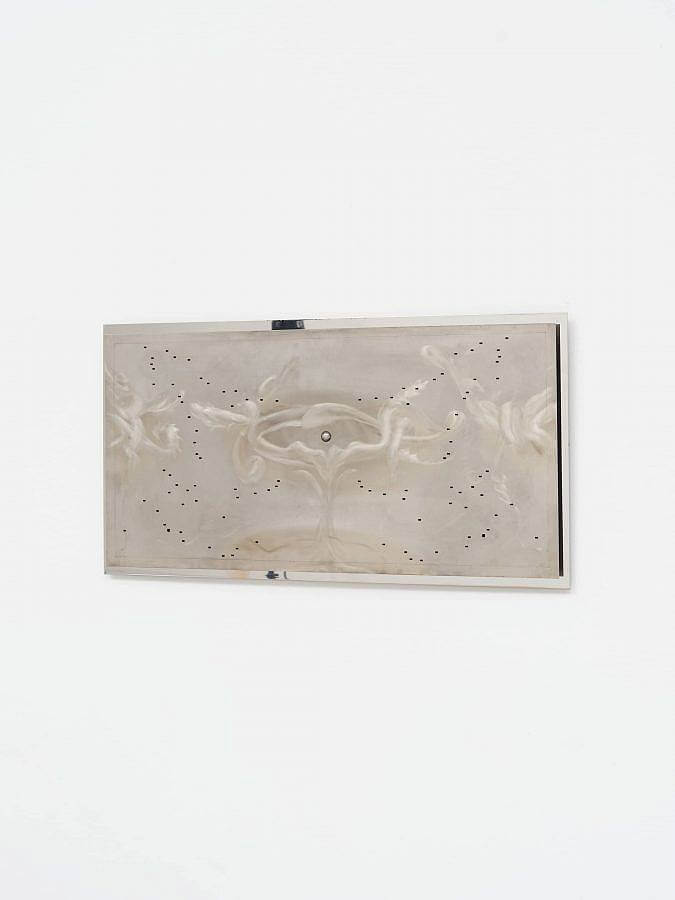

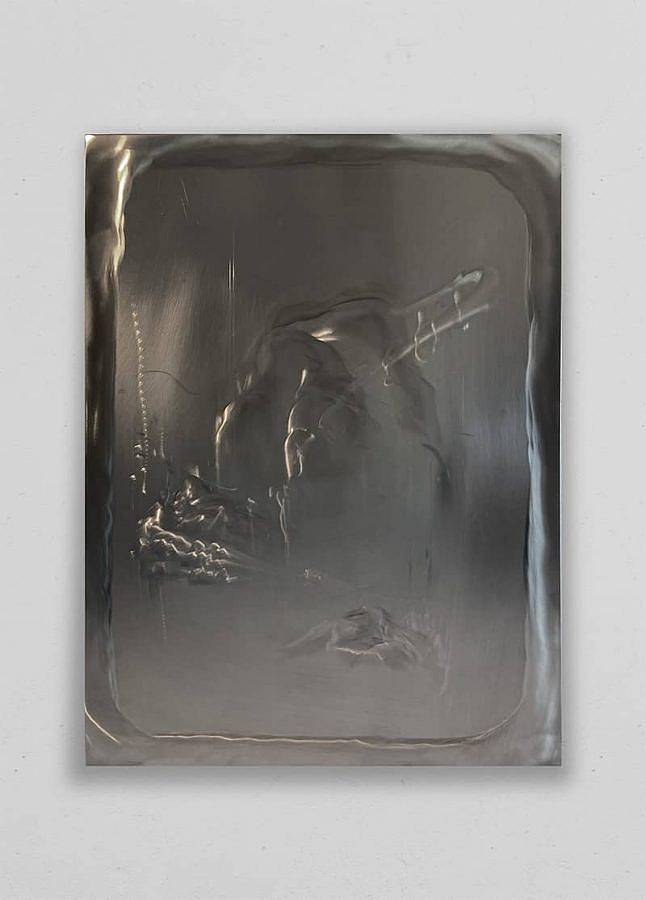

My practice revolves around a technique I have devised which combines gestural drawing with the use of abrasive tools to subtly alter the steel surface, transforming its reflective and refractive properties. My drawings animate under their surrounding light, proposing scaleless fluid cosmoi in perpetual motion.

Misusing power tools to draw, the making of those drawings are bodily demanding performance. Taking into account the velocity of the power tools I use, I consider them active collaborators with whom I engage in a high speed choreography of synthesis.

My practice is a meditation on screens and their profound influence on the contemporary perception of time and space; the increasingly vanishing present and its affluent state of indefinite metamorphosis. As my sculptures continuously regenerate images under the play of light, they become fictional screens for an unfolding parallel reality, whose profile I am gradually shaping.

What’s it like living and working in London, could you tell us how that affects your creative process?

Living in London has two strands for me, there is the living in London and there is the living away from Athens.

The second strand laid the ground for my perception of space and time; my research on the acceleration of our contemporary life and the collapse of cartesian space through technology. Always being in-between places- virtually attaining to exist in two places at the time; experiencing half of that life via simulation, really shaped my approach to reality.

At the same time, London is an overwhelmingly fast city, which can become alienating if you are new. The benefit is you can easily become an observer. And so In my first years here, I felt l was living in the future, which triggered my enthusiasm for sci-fi and the fictioning underlying my practice.

What/who is the biggest influence on your work right now?

The use of stainless steel in the infrastructure of the city, specifically public spaces. I have become obsessed with identifying stainless steel panels across the city and the way they are embedded into the fabric of the space they inhabit. I enjoy gazing at the marks carved on them over time, the reflections of the city life and shadows of the people passing in front of them. I find this calming in the chaos of London, as they become blurred-out short films, abstracting the city life into a flow of movement composed of light and shadows.

What are the main motifs in your work?

Movement, metamorphosis, centripetal force, acceleration, the present.

It is the fundamental question of defining the present which I am mainly interested in, while I gravitate towards different directions guided by research. I perceive the present as a spectrum of continuous metamorphosis. It is within this framework that my metallic works hold an iridescent essence of no fixed image.

What do you want a viewer to walk away with after seeing your work?

I would be happy for anyone experiencing my work, to feel they have been offered a moment of stasis, a rare esoteric equilibrium.

How does your use of light and reflection amplify the stories that you tell through your work?

I perceive light as the narrator, really. The work is not complete without the light telling the story. Last year I collaborated with the filmmaker Yasmin Vardi on the short film: Metaschematism (2023), where the shifting light was the narrator animating the metallic drawings. The film is a fictitious exploration of how the metallic drawings have come to existence, underlining the co-authorship, primarily with my tools, but also with light and the metallic surface for the creation of each piece.

To provide a better image, here is an extract from the text included in the film:

“An intense vibration ripples through her body, separating her into ether and echo.

Like a locust moulting, echo unfolds from within ether, leaving ether a mere translucency.

Gleaming in a pearlescent manner their reflection of light abstracts their forms into eternal movements, breathed out from a silver flute. A double attendance; when they unfurl like shadows of her hair strands’ bending movement.”

Metaschematism (2023), D. Yasmin Vardi & Ellie Antoniou. Experimental Short.

Full HD Video, 08:16 Minutes.

What do the different stages of your process look like?

I enjoy drawing as a way of studying references for forms and compositions that inspire me.

I have a growing pile of reference images, from which I draw my selection as if playing yu -gi -oh!, to form the essence of the next work. The use of the same pool of references with different combinations allows for my speculative drawings to exist in the same world, as they share symbols and forms. I draw inspiration from a range of image sources; from dynamic compositions in anime stills and Italian Baroque paintings, to trompe l’oeil details in frescoes, screenshots from figure skating, magnetic fields and star formation visualisations, amongst others.

I work on compositional drawings, which I compare to floor plans of a choreography. I often think of them as looking down on the stage or being the result of a figure skating performance. I number the layers in those drawings to mark the succession of my movements in order to achieve the sense of depth I want. It is very much a map of how I am supposed to move while making the piece; which direction and in which order.

Something that is not so evident in the finalised piece is the bodily demanding aspect of my process and its performativity. Due to the high speed of the grinder, every touch on the metal leaves a clear mark and so for the composition to flow, I need to have an initial rough plan of a choreography, on which I will improvise responding to the collaboration with the grinder. I cannot undo actions and going over areas can be unforgiving. Therefore, the compositional drawings are very important, but also my attention and responsiveness in the movement of the making.

The grinding process is allocating rougher or shinier parts to the surface of the metal correlating to highlights and shadows to create this 3D-like effect; a grisaille of sorts. I enjoy doing the grinding at night, as this allows me to listen to music loudly in the studio and dance freely. This allows my body to loosen up and bring a fluidity to my drawings.

Are there specific indications that a piece is finished, if so what would they be?

It is really an instinct. When I am working on a piece the metal surface appears ‘open’, operable, and when I am done working on it, it appears sealed; as if anything I would add further would appear on top of the surface rather than engulfed in the drawing.

It feels like a portal which is open for a short duration allowing me to make the work.

What is the ideal setting you see your work displayed at?

A metal factory in dim lighting, where I can integrate my work amongst the raw material and the machines. I imagine there being selective spot lighting on areas highlighting different spaces within the vastness of the factory. Ideally, I would like to work with offcuts or directly onto metallic surfaces found in the space. I would definitely collaborate with a sound artist for a piece to echo through the vastness of the factory, building momentum in the space.

What are some recent, upcoming or current projects you are working on?

‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold’, just closed on the 26th of January. The exhibition was curated by guest curatorial duo Kollective Collective and hosted by Tabula Rasa Gallery, London, it featured two other great artists: Ali Glover and Richard Dean Hughes.

Coming up next, I am part of two duo shows: one with Sophie Mei Birkin at The Split Gallery, London, in March and one with Sofia Clausse at Night Cafe Gallery, London, in April 2024. In June I have my solo exhibition at Cob Gallery in London.

Interview conducted by Ricardo Partida