Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

My name is Saffronia. I’m an artist & clay practitioner from Baltimore, Maryland. I’m currently living in Central Maine, working through an artist fellowship at the Lunder Institute for American Art. I spend a lot of time thinking about how earth processes interact with human-built terrain.

What first interested you in foraging clay? Can you walk us through your process?

Foraging clay became part of my practice in graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In my first semester, I worked with Kitty Ross, a ceramic artist who thinks through clay histories. One day, Kitty brought me a plastic bag full of native clay from her land in Indiana. It was yellowy with pebbles and a musty odor. Unlike the commercial grey clay that I had been working with, this material smelled of microbial life.

The next spring, as the ground in Chicago thawed, I began hunting for clay in empty lots around my neighborhood. I felt like an urban archeologist– peeling back the city’s fabric, looking for histories hidden by concrete. My backpack was heavy with zip-loc bags of clay. In my studio, I began experimenting, making Chicago clay bodies, slips, and glazes.

In Chicago’s industrial center foraging clay felt like folding time–digging up a glacial past while marking a present moment. These experiments prompted questions about how the natural world and built environment intertwine. I use foraging as a conduit for a deeper connection to my local landscapes.

How do you think about collecting concerning your practice?

I have early memories of collecting colorful “beach glass” in a polluted tributary of the Chesapeake Bay. There was trash in the foamy water: car tires, rusting metal, plastic bags. There were also crawfish, dragonflies, and mica-rich rocks.

I’m very transient, always moving for jobs and residencies. I collect material along my paths, mapping matter as I move around. I carry buckets of clay in my trunk. Stuff shifts across the earth’s surface. It’s a geologic process on a tiny scale.

I still have Chesapeake beach glass sitting on my windowsill. It reminds me of when it lay frosty blue in a jumble of sand, rocks, and plastic. The glass recalls childhood connections with the post-wild world. In my practice, collected pieces help access material memories of places.

Do you consider an aspect of your practice to be a reimagining of cartography? How would you describe the way maps function in your work?

My work is site-specific. When I have an exhibition, I dig into local land histories. I research practices of extraction and industry to understand how the landscape was altered by human/colonial activity– How have people worked with local materiality and what effect has that had on the environment? What heavy metals or pollutants might be in the soils? What structures or remnants inhabit the landscape?

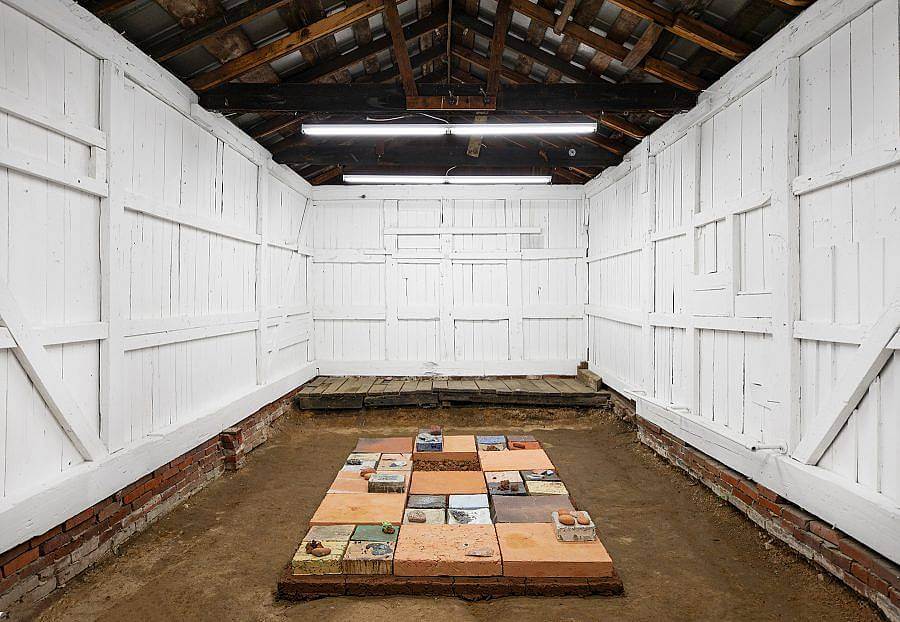

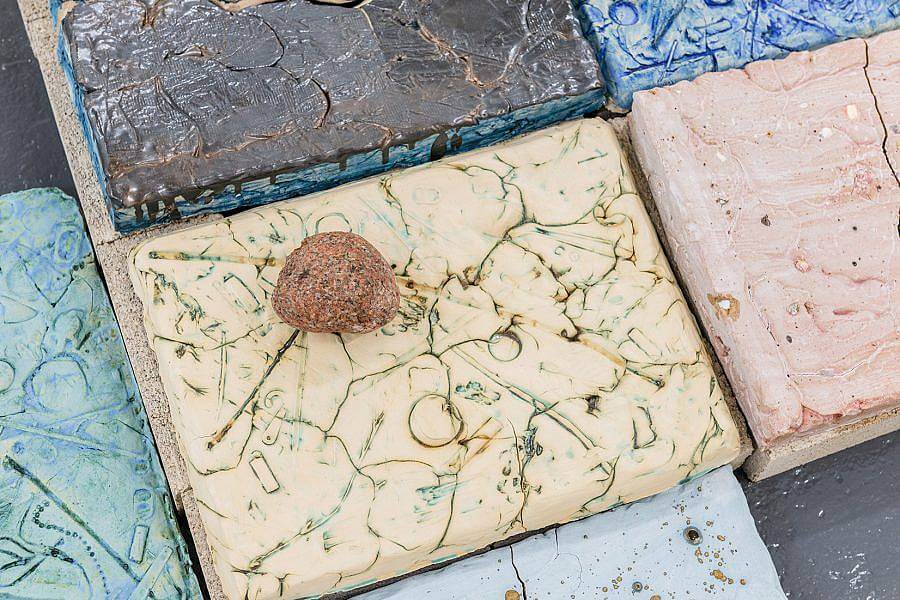

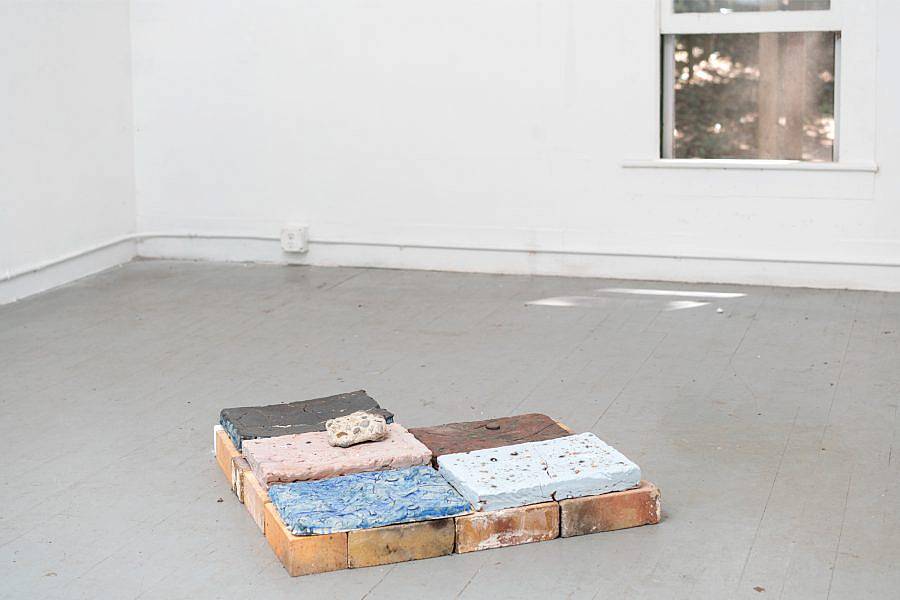

Foraging clay is a way to connect with new geographies. My ceramic floor installations piece together blocks of clay, soils, glass, and stones I’ve harvested in different places. I’ve made blocks from Western Mass, Chicago, Knoxville, Maine, Michigan, Wisconsin–all sites I’ve built relationships with in the past few years. The blocks of clay cohere as a new ground composed of a collection of places. A mosaic that materially maps my migrations.

Many of your floor pieces are incredibly evocative of ruins–the remnants of man-made matter altered by the movements of soil and clay and vice versa. What are some of your thoughts on this idea and how do you consider the continuation of life in the “ruins” of post-industrial modification?

In the post-industrial city where I grew up, I was surrounded by decaying infrastructure. From childhood, I knew that the human-built world has a lifespan and will slowly break down. I’m fascinated by the fact that rocks are decomposing. Stone feels eternal, but it’s in a process of weathering into bits. Clay is made of tiny flakes of rotten rock. Processes of decomposition and regeneration stretch beyond our brief human moment. Some geologists think that clay was the birthplace of life on earth. That to me is a hopeful fact.

Tell us more about your walks. In what ways can walking become an extension of studio work?

I’m very fond of Rebeca Solnit’s writing about walks. In her book Wanderlust, Solnit writes that “the mind, like the feet, works at about 3 miles per hour.” When I walk, I notice things in the landscape. I make connections, work out problems, find pathways.

Early in the pandemic, I drove to a nature preserve on the outskirts of Chicago. My MFA exhibition had been canceled and I lost access to my studio space along with all my work and tools. It was a hard time.

A couple of miles along the trail, I found a vein of clay in a muddy tire track. I scooped out a handful and molded the yellow clay in my hands as I walked. Walking and squishing the clay between my fingers gave me affirmation that I hold my practice with me as I traverse space.

Tell us about VIRAL ECOLOGIES and its inception.

Viral Ecologies is an online platform co-curated by Rosemary Holiday Hall and myself. It’s a digital space– a collection, container, notepad, network– through which artists and thinkers participate in acts of noticing. We publish content that centers around emergence, the idea that small actions underpin complex systems.

The project grew from the early days of shelter-in-place. We created Viral Ecologies as a collective space to look closely at obscured structures revealed through the pandemic. Our first issue was released in September 2020 and features six artists whose work investigates bodies and landscapes through personal, spatial, and ecological modes.

Viral Ecologies remains poignant through our ongoing pandemic era. We’ve recently published our fourth issue of works– a quadruplet of projects that gnaw, draw, pickle, and probe relations between animal, vegetal, and microbial beings. Viral Ecologies connects folks who share an interest in the everyday ecologies that shape our lives.

What are some of your essentials in the studio and beyond?

Plastic buckets, a trowel, zip-lock baggies, plaster slabs for drying and wedging clay, a sturdy wooden clay-shaping rib, and a flexible silicone rib. Also essential are these ingenious plywood brick molds that a colleague made for me. A hammer for smashing ceramic, soils, and rocks. A tea kettle, rice cakes, and peanut butter.

Also, books! On my desk today: Vibrant Matter by Jane Bennet, Soil Keepers by Nance Klehm, The Potter’s Complete Book of Clay and Glazes by James Chappell, Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Early Potters and Potteries of Maine by Manlif Lynn Branin, Craft; An American History by Glenn Adamson, The Papermakers Companion by Helen Hiebert, Quilts; Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum, The Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet edited by Anna Tsing & Gan Bubandt.

What are you reading right now?

The Underland by Robert MacFarlane and Barkskins by Annie Proulx.

Any upcoming projects?

I have two projects that I’m working on through my fellowship at the Lunder Institute. One is a ceramic floor installation that incorporates clay blocks from Wisconsin, Michigan, and Maine (three of the places I’ve been in residence this year). This piece will mimic the geometry of a quilt– building from my interest in quilts as a historically women’s craft of map-making, storytelling, and material ecology. It will be installed in a two-person exhibition with Faysal Altunbozar at Roots and Culture next April.

I’m also working on an oral history project surrounding Maine’s papermaking industry. I hope to make a book, collecting a constellation of stories surrounding industrial pulp and paper. The book will gather stories from mill workers, forest ecologists, Wabanaki land practitioners, loggers, fishermen, farmers– folks affected by the byproducts of industrial paper in complex and nuanced ways. This book will be released at the completion of my fellowship.

Interview composed by Ruby Jeune Tresch.

Edited by Joan Roach and Ruby Jeune Tresch.