Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and what you do?

I am an artist and educator based in Chicago. I make textiles, sculptures and installations that often become sets for performance works. In my practice, I research labor histories to investigate relationships to material culture and the systems of production that have generated it throughout time. My primary interest at the moment is image-making in quilting which I explore through individual and collaborative projects. I’m drawn to the accessibility of this medium and its historical precedent of recording biographical information about the life and surroundings of its makers.

Last time we spoke you were getting ready to go to Hungary for your Fulbright fellowship- can you summarize how the trip was and what projects it inspired?

It was an enriching experience on many levels and I am deeply grateful to Fulbright for the opportunity. I joke that Budapest is my aesthetic city soulmate because I would walk the streets for hours making drawings and photographs with an old Nikon N80, endlessly intrigued by its architecture, fashion and ways that people navigate the unique language. It is a city I feel drawn to and continually revisit throughout my life, which I formerly attributed to my family lineage. However, I learned on this trip that we are actually from a small town in Slovakia that was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time that my ancestors immigrated to the USA. This is one of many discoveries. Another important one is the famous baked good, pogacsa!

I applied to the Fulbright program in Hungary to learn a resist block print, indigo fabric dying process called kékfestő that came to this region of the world in the 17th century. China, Japan and India have been doing it for thousands of years but I was specifically interested in its development in Hungary and how that relates to the country’s complicated political history. It was a major export until the Socialist regime took control in World War II and shut down any artistic practice that was deemed “creative.” The family-run dye houses that remained were legally able to dye fabric only for state-run agency uniforms such as manual laborers and factory workers. I noticed that Budapest city Parking Inspector and MAV (public transport system) employee uniforms’ color remain this iconic indigo which I find to be a fascinating symbol of governmental power intersecting with craft. The decorative, blue and white patterned material is made by only 6 families in present-day Hungary and I was fortunate to work with 3 of them to learn their methods and family histories. The Győri Kékfestő Műhely was particularly generous in allowing me to print my own yardage in their studio with block patterns that hadn’t been used in 300 years.

I spent time at the ancient Roman site of Aquincum in Budapest, Empuries in Spain, and a bit of time in Rome learning about ancient building methods. I often thought about how Romans were able to conquer with their innovative building techniques, changing the cultural landscape of the world. Amongst the crumbling ancient stone and brick, I was always looking for signs of a human hand. At the end of my Fulbright I made a series of small quilt works in direct response to Aquincum that were formalized into a solo show Rope a necklace to my tongue at Faur Zsofi (curated by Veronika Molnar).

What is The Freedom Quilt project?

The Freedom Quilt is an ongoing collective making endeavor that I began in Hungary when my Fulbright ended in May last year. I designed it to discuss free speech and create a collective kékfestő quilt, celebrating 30 years since the Socialist regime ended. I chose to work closely with the Hungarian Patchwork Guild (HPG), presenting the idea to its 425 member annual conference, because the guild was formed as a direct response to the regime change, in 1989. After my research period on Fulbright I understood kékfestő to be a culturally significant material that many quilters use in their work, and the US Embassy in Hungary provided me a grant to fund programming related to the anniversary. I carried out a series of 8 workshops around the country during which I lectured on the rich history of American quilting and its relationship to cultural identity and creative expression outside of institutional frameworks. Attendees were also provided with basic sewing and appliqué instruction in order to make a quilt block in response to the prompt “what does freedom mean to you?”

The completed quilt consists of 108 blocks by workshop participants and HPG members, exhibiting a broad range of individual gestures. For me, the work represents a foundational truth about quilting, it being an accessible medium that anyone can participate in because the skills and patterns have historically been freely shared. It was crucial to me that a collection of varied perspectives were present in the final work; the youngest participant was age 4, the oldest 93 and women traveled from Romania, Serbia and Croatia to attend the workshops during which a translator facilitated fascinating conversations about individual experiences of women making quilts through two very different political regimes and economic structures. The HPG helped me construct the collected blocks into a quilt during a public quilting bee at an open air ethnographic museum over the course of four days. I see the resulting 11 by 15 foot quilt as a complex index of visual symbols that will continue to be exhibited as an example of temporal union, international exchange, and resilience in quilting communities.

What have you learned from teaching the Freedom Quilt projects workshops and working with the participants?

The participants were so generous and welcoming to me all over Hungary, including very small, isolated and politically conservative towns. I felt that most of the women I met were confused about my interest and commitment to a practice that is typically embraced by older generations (I am 38), but this led to incredibly rich conversation that proved the practice to be an equalizing force across generations, wealth status, race, political views, etc. The workshop I did in Szeged stands out to me because the group of participants took me to their small town of Algyő the following day to show me their community center that was full of their beautiful work. When I asked how it accumulated and why they don’t sell it they said that they prefer to give it to people out of love or exhibit publicly instead of entering an economic system with a practice that means so much to them. The older women in the group expressed nostalgia for the Soviet era because they claimed there was more time in their schedules for family, quilting, and self care. As an American that admittedly does not thrive in rule-based structures and coming from a late stage Capitalist system, I found this really interesting. It made me want to continue facilitating complicated but honest conversations between people because it’s valuable to remember that there are so many perspectives beyond our own.

While your work is craft based, it is also very participatory. How do you go about designing and executing events and workshops?

I aim for participants in both my performances and social engagement workshops to feel a sense of connection with one another while also having an individual experience with the medium or moment. I spend a lot of time meditating in my studio in the presence of my in-progress textile works which informs the format for my performance works. This usually looks like a group meditation in the exhibition space, in the presence of the work and sometimes involves the participant to directly interact with small found object sculptures that I’ve made. I aim to energetically hold a space for the participants to feel comfortable following the path their hearts and minds take them while I slowly read a pre-written script. The language tends to be illustrative, visual, and based on the imagery I see in my own meditations.

What role do artifacts and archeology play in your work?

I am interested in the comparison between art making and archeology as they are two different ways to experience discovery through physical objects. We have extremely intimate relationships with textiles throughout our lives but they don’t survive as stone, clay and brick artifacts do. In response to this, I have continued making small quilts that record my findings at archeological sites of ancient architecture in Hungary, Croatia, Spain, Italy and Turkey. Their imagery uses the forms and materials found in the sites to animate long forgotten physical gestures of the people who built and inhabited them. In casting these reflections backward, I play with lineages of human expression and compact the notion of time.

What are you working on right now?

I am sorting through hundreds of film photographs, small drawings, and a collection of poems that I made while traveling between 7 countries over the last year and a half. I am especially excited about the poems that I wrote at sites of ancient architecture because I like to think that I gleaned something about the people that built and inhabited them through my meditative poetic practice. When I was traveling, I made a traveling suitcase studio with essential tools and materials that went everywhere with me. I’ve now amassed so much research material that I would like to formalize into an exhibition and an online archive.

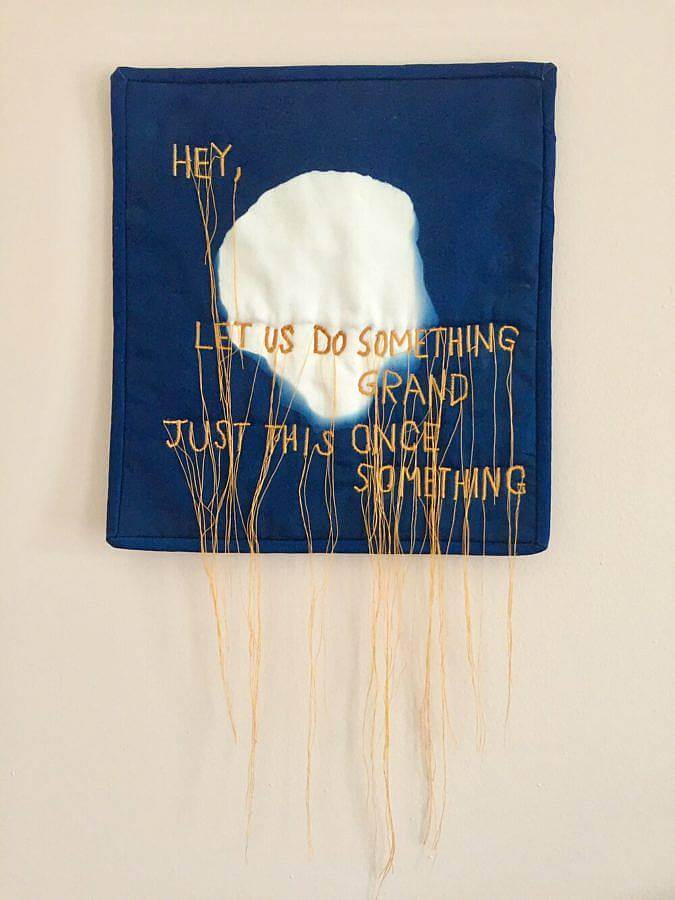

In addition to the Freedom Quilt exhibition at Andrew Rafacz, I currently have a sound piece streaming on Utopia / Dystopia Sound Landscapes radio that was organized by french artist Marianne Villière, a stitched cyanotype work in ArtGym Denver’s virtual exhibition and an edition of 10 self published books of poetry & drawings available at MPSTN in Fox River IL.

How has covid-19 affected you and/or your practice? What have you been doing at home?

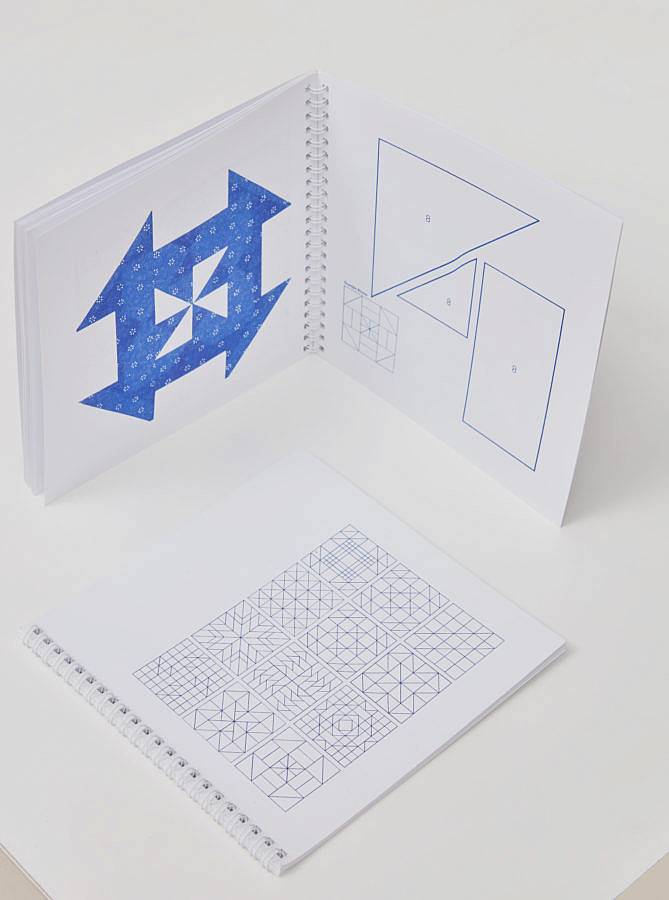

I was able to install the Freedom Quilt at Andrew Rafacz Gallery for its first ever exhibition and book release event at the end of February, but unfortunately it hasn’t had many viewers due to Covid-19 (You can contact the gallery to schedule a private appointment or follow the project on social media for future event updates). RisoPlant Budapest published an edition of 100 books, designed by Ryan Ingebritson, that double as an exhibition catalog and instruction manual for creating 12 different blocks that are part of the quilt. Copies of the physical book can be purchased or a PDF downloaded for a ‘pay what you can’ option on my website, and I plan to circulate the recreated blocks on the project’s social media outlets. I will actively seek new opportunities for future exhibitions and workshops hopefully starting in Chicago as soon as the city begins to reopen.

In response to the confusing perception of time that I think we are all experiencing in quarantine, I’m making a 4’ x 6’ quilt of small cyanotypes on fabric. I’m piecing together images that were created with the mediums of sun and moonlight over the course of a day. I made one each hour for 24 consecutive hours using a 3D printed version of the Ludovisi Fury sculpture made by Matthew Brennan. I learned about this 2nd century AD Roman copy of a Hellenistic work while on a residency at the American Academy in Rome earlier this year and found the most common question asked about the androgynous head to be – “Is it sleeping or is it dead?” since figure sculptures from this time rarely have their eyes closed. I’ve also been selling small, commissioned stitched works with these cyanotypes through Instagram and my web shop. The current circumstance is making it difficult for artists like myself to find income so I appreciate that people with the means are buying work from artists right now.

What are you reading right now?

I was recommended to read Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari by a friend while we were visiting the Göbekli Tepe site in the southeast part of Turkey. It’s a great read for anyone interested in a summary of human evolution from hunter gatherer societies to the current world. I am also rereading Sexual Personae: Art & Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickenson by Camille Paglia which continues to align with my interests 6 years after the first time I read it.

Interview Composed by Madeline Olson