Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I’m a 30 year old Canadian – Ukrainian, currently based in London. I was raised in a quasi American suburban dream: my parents were born to Ukrainian immigrant/Catholic refugees, so there was a romance with the endless material stuff newly available within capitalism: endless food was negotiated alongside a sort of horror of my own body as a female. My practice has been largely informed by that history, moving from a capitalist critic to a new materialist play and now I am interested in a sort of wider ecological picture: looking at how definitions and dynamics of life/non-life/death inform culture. I usually use large scale fleshy organic slabs of SCOBY, which I manipulate with custom made mechanisms, but I have other directions of research including film making.

What is a SCOBY, and why does it keep showing up in your work?

SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture Of Bacterial Yeast) first grows as a skin on the air-liquid interface of Kombucha (the fizzy health beverage). It becomes thicker and thicker over time, taking the shape of whatever container it grows in. Eventually, SCOBY turns into a fleshy, beige and juicy gelatinous matt that smells pungently of vinegar. Acting as a protective plug that shields the co-cultures underneath it, SCOBY is technically a byproduct of relations between the bacteria and yeast within kombucha: the yeast metabolizes sugar and makes alcohol that the bacteria in the brew consumes.

Especially at a large size (200 kilos), it is viscerally difficult to know what SCOBY is or categorize it. It’s fascinating and repulsive and has a lot to give, so I have a lot to give it. Also, it has just been around me so much as the second project I made with SCOBY took five years to complete. It was just always in my mind, I think it literally started to grow in my brain and now I am not sure if I am the one making the decisions or the SCOBY is.

When did you first cultivate a SCOBY?

In 2017 I was cultivating at home to make kombucha, and so was my ex-partner in a really dedicated way. I loved having it growing in my bedroom, and was fascinated by the material, so I ended up growing it for an installation I was building at the time. The installation was based on holding things in between states of living and dying in these clean acrylic boxes in a white room. I was working with the safety of what looks sanitary, and the sort of line between intrigue and repulsion when you realize that the boundary between may be too small, ie. are the walls of the acrylic boxes actually thick enough to lock toxins within them? For this install, I grew my first largish scale SCOBY in my parents bathtub. When I first peeled it off the liquid I was amazed by the material. Quickly, awe flipped into repulsion and I questioned my sanity for growing it. My mom came into the room and had the exact same reaction- drawn in, and then retreating back in fear. The origin story! I have told it so many times, and am so bored of it – but- it really was the definitive moment which started this six year journey into working with the material.

What does your studio look like?

It changes all the time. Now it feels like a neat and soulless storage space: lots of different sized drums, endless boxes in the corner and a SCOBY in a plastic bag lying on the floor. It matches my mood about my practice after a very intense period. Last year, my studio was in a different building down the street in what feels like the farthest corner of London. I couldn’t use it at all because it was so full of different sized tanks and vessels growing SCOBY for the show I had at Gossamer Fog in September. It stunk and the people on my floor endlessly complained, constantly feeding notes under the door and knocking on it the second I would enter to tell me to stop growing. So I basically got kicked out of the studio, I hope this one lasts longer.

A lot of your work involves the lifting and/or movement of the SCOBY after growth, either mechanically (as in Residual Yeast or Life Models) or by a team of people (Symbiosis Performance); could you speak to that?

It all comes back to this moment in the bathtub! I realized that the amazing thing about that was lifting the SCOBY off the liquid. I think that is for two reasons. Firstly because you could sense that this growth necessitates a sort of perfect stillness, once broken, the SCOBY would never float again. Secondly, you really get an understanding of the material that way. It comes from the liquid, in the growth tank it developed in, and you see the thickness of it, the way it stretches and moves with motion. I became kind of obsessed with that lift, this moment of reveal. I wanted to mechanize it because I wanted to have this sanitized, industrial distance, this potential sense of safety for perception, much like the thickness of the acrylic walls in the install I was referring to before.

The teams of people moving the SCOBY was a practical decision at first. It started with the video Moving Thing, which documented peers moving out a giant SCOBY that had grown too large in a tank while I was developing a custom-made robot. Later it became this live performance, SYMBIOSIS. The difference is that the interaction with the SCOBY becomes more intimate, you no longer have that mechanical distance. In a way it is like performing my studio practice, with more people and ease.

Any standout shows you’ve seen recently?

I have a friend, Yen Chun Lin, who created an overnight event at the ICA in London. A Nut Falls Twice… took place overnight, with a series of performers exploring the idea of falling: falling asleep, falling in physics or falling in love. Viewers were invited to sleep within the installation, and so the idea is that you would slowly wake up in different performances. Each performance was unique, using light and sound in different ways, but being bound to this installation environment. It was playful and beautiful, and was a really nice depiction of a community that Yen is a part of.

What was your MFA experience at Goldsmiths like?

It was really nice to be honest. I made a group of international friends very quickly. We were all so romantic and enthusiastic about making art and talking about it. We’re still close and support each other’s work in a way that makes being in London possible. Also some of the teachers were great, the program was invested, it was a really positive experience looking back (I’m saying all this now, but during the course I was complaining constantly about the lack of trolleys). I don’t think Goldsmiths is as positive for everyone, especially now as financial pressure runs this and other universities very thin.

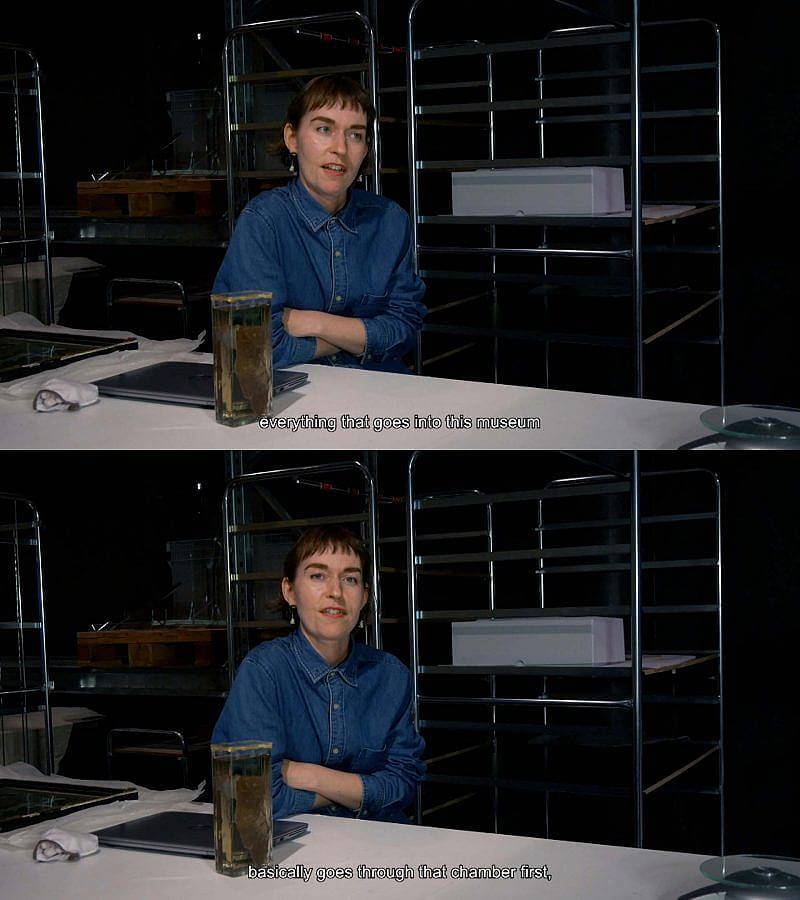

Can you talk about your video piece ‘Heat Treatment’?

The Heat Treatment is a short experimental documentary that follows conservationists at the Norsk Teknisk Museum in Oslo. It depicts the toxic processes happening within conservation that create the infinite objects that the museum is based on. It started by looking at the heat treatment itself, an internationally used method of conservation that eradicates insects and microbial life from objects by putting them into a thermal chamber that reaches 58 degrees over 24 hours. I initially saw this as a sort of baptism through fire into the museum’s collection, and was thinking about wider conceptual ties to global warming.

When I was at the museum I realized there were more related processes in conservation, which I saw as being anti-life. Take the rooms with low levels of oxygen that prevented workers from occupying for long periods of time as they would get light-headed. Or, objects which had been treated with toxic chemicals such as DDT historically, giving nerve damage to conservations. I was interested in the toxic effects of creating a sort of utopian infinity, especially in relation to proximate organic bodies. My next film, Polar Bonds, will be looking at literally poisonous collections that are far more common than the general public knows.

How would you describe your relationship with the scale of your works?

I’m tired of it, my body feels it. I do not have a large team helping me do things, and it’s exhausting. But I think it’s necessary, it’s important to have that kind of scale because the last thing these installations are trying to be is polite, they are trying to confront the human body and it is necessary but exhausting.

What pieces of art or artists would you say have had the biggest influence on you?

Jon Rafman’s disgusting photos of keyboards and computer screens deep in human junk and decay had a huge impact on me, and started this research in disgust after I became completely taken over with that emotion triggered from his exhibition at the Zabuldwich collection in 2015.

You recently had a show at Gossamer Fog in London – could you talk about that work and how it came about?

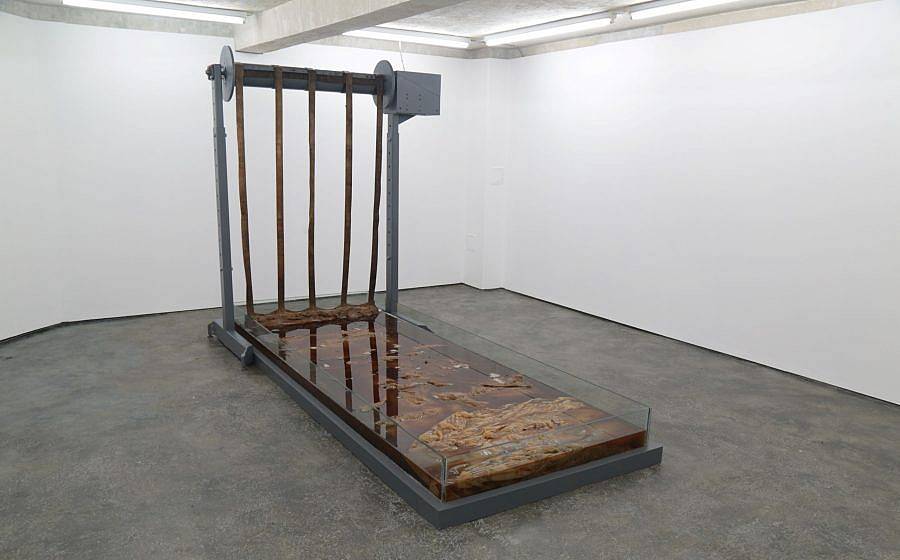

This exhibition centered around the work I was discussing earlier that took five years to develop, named Thermaloop. In it a 300 x 120 cm SCOBY, which was around 200 kilos, was lifted out of its tank vertically and then rolled around a drum at the top point of a custom-made mechanism. The functioning was possible as the SCOBY was sewn to lengths of webbing which were attached to the drum. So as the drum spins the webbing the SCOBY slowly lifts, and then starts to roll around the drum before being put back into its place in the same manner reversed, a loop which lasts about fifteen minutes. Fruit flies lingered in the air in the place, along with the smell of vinegar. The install was presented in a sort of monumental manner, in a white room which you enter after descending the staircase from the bustling deptford high street. This was basically the end point of realizing that lift I wanted after the bathtub moment in 2016.

Besides that install, there was another room where I projected a film I had made in the summer, taking place in the Bird Gardens of Scotland. The film features mostly turkeys eating SCOBY, with some other birds, like chickens and a curious Toulouse goose stepping in the material. I have been working with birds eating SCOBY for the last couple of years after I saw a video on instagram of someone doing the same. It was a sort of holistic sustainability person that had a farm, a kombucha fermentation and a backyard flock. I thought there was something totally uncanny about the turkey’s fleshy wattles matching the materiality and jiggle of the SCOBY. I think it also does what my wider practice does with SCOBY, which is challenging this image of organic, sustainable aesthetics, which are often kind of bourgeois and polite. Perhaps these aesthetics make sense for the daily life of practitioners, but it is kind of bizarre with the horrific background of environmental destruction. New necessary assemblages to the world in the face of climate catastrophe are not going to be comfortable. I think more realistically, I would expect to be either weirded out, disgusted or terrified.

Do you have any upcoming projects that you can tell us about?

Yes, so I am working on that film that I mentioned. Otherwise, I am aiming for my upcoming solo exhibition in Sismógrafo in Porto to have the next SCOBY install, in the seemsveryfarbutactuallyisquiteclose year of 2025.

Interview Conducted by Milo Christie