How did your interest in art begin?

I grew up in a boat-shaped house in the middle of the Serra de Collserola Natural Park, Spain. I had a transient childhood that mirrored my home’s design – I was raised by proto hippies, who named me Selva (Jungle). Like my namesake, I was immersed in the natural world where hand-made objects and animals filled my day-to-day life. I transferred schools seven times and travelers faded in and out of my childhood. It was a group of Rapa Nui from Easter Island who taught me how to stone carve for the first time. Amidst the tumultuous nature of my household, I absorbed a deep sense of calm from my natural environment and began to craft a sense of liberation through my artwork. The mindful process of gathering resources that I found around me as a child has carried through as an integral element of my artwork as an adult.

What artists have you been influenced by?

If I had to choose one I would say Peter Wastell. My parent’s relationship was nearing extinction and so followed my father, who quickly faded from my everyday life. Peter was my next-door neighbor and had a son of the same age. I quickly became “the daughter that he always wished for”, yes, creepy. I spent countless hours in his studio learning from him. He had a very strict art-making process. He made his paint, gesso, and stretched his canvases. He was specific on the placement of staples and the perfect sound a canvas should make when it is at its ideal tension. He thought that the back of a painting should be treated with the same consideration as the front. He was passionate about nature and animals. Later in life he developed severe myasthenia and lost control of his muscles, unable to lift his head, wash, or paint he took me as his assistant. It was a very special time for me. His studio was in a very tiny space by the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Pi in Barcelona. This cathedral has one of the largest rose windows in Europe. My work “Remains” was inspired by its geometry and history. His claustrophobic space was both studio and home. No bathroom or kitchen. As his health rapidly deteriorated, it was very shocking to see a human body so lifeless but alive in thought. Despite all his struggles, he kept on making these series of large scale paintings. He would hand me his sketchbook and make me paint them for him. The last time I saw him after years of separation, was at his funeral, dressed in white, on January 23, 2019. The same day my son was born.

In many of your works, specifically “Entre Nosotros,” you worked with human donors and went through a casting process to form massive sculptures with unsealed concrete. How did this project develop and what did the casting process entail?

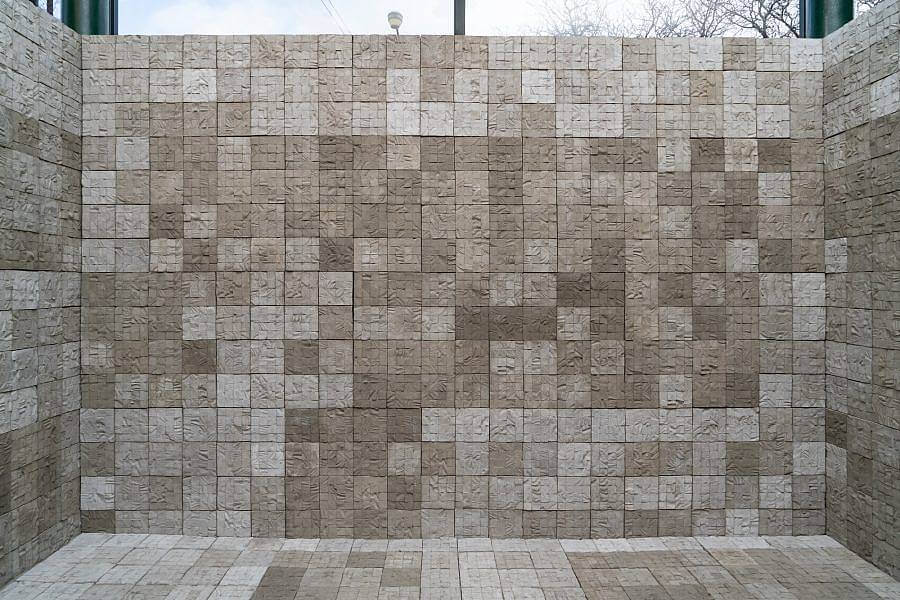

The process of working closely with dead human donors started after I applied for an independent study at the Yale School of Medicine when I began my MFA. It was a long journey where I was able to research the human body as an object. After several projects, I began to focus on the wrinkles. I was amazed at the richness in textures the human body develops, the stories embedded on their surfaces, the fragility and vulnerability of the human afterlife, and the silence that they present. I started making molds of parts of the body in over a hundred donors. It was a very intimate process where I got to know these people after death spending countless hours working with them. It was a collaboration. Leaving the concrete unsealed was a way for me to keep the donors alive since the concrete absorbs the moisture of its surroundings and of the visitors who experience the work.

Can you discuss your most recent work, “Hysteria,” that’s currently on display as part of your solo exhibition of the same name, at the International Museum of Surgical Science (IMSS)?

In a past show at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) called William Hunter and the Anatomy of the Modern Museum they displayed over 380 objects from Hunter’s collection including his contribution to obstetrics. It was my first time showing my work alongside the work of a doctor. William Hunter was an anatomist physician born in 1718 and a pioneer in the study of the pregnant woman. It was awakening to learn how doctors did their research in a world where they had no boundaries. Issues of ethics involving the use of the dead human bodies came up as well and started to gain a lot of interest in the history of gynecology. At that time I was working alongside a surgeon who taught me how to look at the human dead body, how to dissect it, how to respect it and appreciate it, and most importantly, how to thank the donors for their consent to be examined and studied.

Hysteria was the result of my residency at the museum where I was able to research their collection. My previous show at YCBA and the difficult birth of my son drove me to focus on obstetric objects and historical paintings at the museum. I was immediately taken by the forceps and the evolution of their form and materials, as well as the speculum and the controversial history of its invention by Dr. Sims. This would become the centerpiece of the main installation; an obstetric table from 1931. This is an object that I believe many viewers will have a direct personal relationship with and will invite visitors to consider the effects of the institutionalization of medicine and subsequent imposition of strict boundaries concerning gender, race, and authority in its most basic practice. Hysteria centers both the memories imbued within and the imprints of past patients upon these enduring pieces to explore the nature of womanhood as a condition defined by conflict, pain, and transition, constantly positioned at the very precipice of life and death.

Thorns draw so many associations to them. What about the nature of thorns drew you to use them as a material object?

My work is deeply connected to my personal history. My mother’s name is Aranzazu which in Basque means “you in between thorns”. That’s exactly how we lived, surrounded by thorn bushes, an indigenous plant of the Natural Park of Collserola. It was this connection that first made me investigate the material and find out more about its associations and qualities. In the case of the installation “Hysteria” is made out of thorns branches woven with a ligature, it was a very slow process both technically and conceptually. I began with an investigation of the resources in the museum’s collection. Among the collections, I found a gynecological table produced by Hamilton Medical Furniture in the 1930s. I saw the memory of the presence of the patients that were treated on this empty table imprinted on its surface. I choose to use thorny stems to define a perimeter that surrounds the obstetric table, like curtains in an examination room. The correspondence between the table and the curtains define their relationship. The thorn stems were split in half, having the thorny part facing the interior of the space, and the soft exposed part is pointed outwards and you can look through.

What process do you go through to obtain your ephemeral natural materials and how does this relate to your overall practice?

All of the materials I use in my work have been and will always be ethically sourced by my hand – I carefully scan my environments to choose each new project. For one of my latest pieces, “Velo de Luto (Mourning Veil),” I drove from Chicago to Kansas to collect the wings of the cicadas that swarmed in that year, which only happens every 17 years. I waited for them to die. I wait for all of my materials to be discarded or dead before I use them.

The thorns for “Hysteria” currently on view at IMSS were all collected around the house I was born, selected, cut, and shipped to the USA. I need to be truthful to my materials and their unseen force imbued on themselves. I tried to find these thorns in the USA and I encountered the same plant but it was not carrying the energy that I was looking for. I have also had many problems shipping my materials. While doing my MFA I was prosecuted by the US Department of Agriculture who came personally to my school looking for me. In their emergency action notification, they described the thorns as “birds nest made of sticks with bark”

Although you’re often working with organic materials–cicada wings, human hair, thorns, and human skin–your works often take very organized and meticulous forms. You’ve made a gridded wall, a triangular veil, a carefully constructed curtain, What’s the inspiration behind your use of organized and repeated patterns that come together to form a larger structure?

Repetitive processes frequently occur in my projects; through multiple castings, sewing, collecting, and weaving, there is a cycle of accumulation and utilization. In the process of accumulating and collecting I come to understand the nature of a thing, the language that the material speaks and they give me time to think and make connections.

Keeping order and organization around my work helps me contrast the chaos and disorder in my upbringing. It’s a form of meditation and mimicry of nature. The pieces, on a personal level, are cathartic because I often work from personal experience. Finally having some stability in my life is giving me a chance to speak from a more distant point of view.

The grid choice on “Entre Nosotros’” installation was a decision made to give the same physical space to each of the donors. Each donor occupies a 2” by 2” concrete tile, making it visible that death is an equalizer.

What motivated you to produce “Velo De Muto,” your other work currently up at the International Museum of Surgical Science?

I have a really special relationship with my mother who I often visit but, due to visa issues and the current pandemic, it’s been already two years since I last saw her. This piece reconnects me to her. It speaks of our shared experiences living in a patriarchal society. The joining of wings serves as a metaphor for the decay of life, both literally through the wings of the cicada and figuratively through the veil traditionally imparted on women who have lost husbands and sons. It is through these remnants, often left decaying and discarded as the cast-offs of death and loss, that we learn the most about life and can reclaim and reimbue age-old symbols with new meaning.

What is your current studio/workspace like?

Imagine a rectangular space where over fifty wasp nests hang from the ceiling, boxes of dandelion seeds are stacked on shelves, dried lettuce, random tools, and tons of ideas wait to be revisited. I have a very fragile process so I get very nervous thinking of someone coming to my studio and suddenly breathing over something I am working on, sometimes that’s all it takes to break it!

After I graduated I went back to Spain to build my studio with all the details I wanted in place. There were Catalan modernist tiles, restored doors collected in abandoned houses–things I have been collecting my entire life. I am passionate about construction, that’s my number one hobby. Unpredictable life events sent me back to the US unexpectedly so I wasn’t able to even use it. All the work I’ve made this past year and a half it’s been produced in places like a laundry room, an unheated garage, and friend’s studios. As you can imagine, it has been hard to produce large scale installations with continuous distractions and little space. I now have a studio at Mana Contemporary. I am so thankful to have a space surrounded by like-minded individuals where I can concentrate on my work.

Do you have any recent or upcoming projects or shows?

Both exhibitions currently on display are closed due to COVID 19 restrictions. The Long Dream at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago is open from November 7 through January 17th and my solo exhibition Hysteria at the International Museum of Surgical Science will run through January 17, 2020. You can see images of the work on both the IMSS website and my Instagram.

Interview composed by Amanda Roach.