Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I drift, I associate, I inquire and long through a boudoir, a psychoanalyst’s office, through department stores edging toward defunction, through the Les Puces flea market in Paris, libraries, and what I call a ‘flow of images’. I intimate questions across a studio art practice, writing, perfumery, curating, and teaching. I attempt, with some desperation, to not repress. I read and I nap more than anything else. I collect bones and simmer them into stocks. I pay close attention to my own remembering. I soften.

How would you describe your upbringing in Baton Rouge and what brought you to Chicago?

Well, I was raised in an evangelical Christian, politically very conservative household. My sibling and I were born as conjoined identical twins, separated four days after birth—hence a lot of ‘twinning,’ copies, and non-identical reproduction as methods in my art work. My childhood was steeped in a really eccentric late-twentieth century southern gothicism, and while my family’s religion kept us at some distance from the revelry endemic to the area, the flamboyances of Mardi Gras, drag queens, and queer communities like Baton Rouge’s Spanish Town reverberated around us.

I was surrounded by indelible, extraordinary women. Both my grandmothers were self-possessed, badass role models. My mom is a disciplinarian by temperament; rules are clarity for her. She was very large before she became diabetic, and at one point shortly after I started seeing my partner Eric Ruschman, the two of them had nearly identical bowl cut hairstyles. One of my aunts is Thai, is hilariously jocular, and smells like jasmine and cigarettes. Another aunt wore long acrylic nails and competed in rodeos. Miss Belle was a shut in who collected costume jewelry and bells after her namesake which lined the walls of her tiny home. Bobbie and Nelda were unmarried sisters who cared for their invalid mother and collected porcelain dolls—they would bring Michael and I small pieces of lamé, velvet, or sequined cloth that served as the basis for most of our make believe. Mrs. Darlene Montalbano wore lots of makeup and flashy clothes, and I thought she resembled a regal angel fish (Pygoplites Diacanthus) I’d seen at the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas in New Orleans. The women at the predominantly Black church my parents attended would cover themselves in powders, lotions, and hair serums—some would wear Sunday hats to services; others would wear house slippers. Mrs. Celie went to a big Baptist church down the street from our neighborhood: she was very tall with an even taller beehive hairdo, only wore pink, accented with an array of butterfly brooches arranged across her ample bosom, and she carried a small ice chest filled with cans of Dr. Pepper with her everywhere she went. I could keep listing but suffice to say, these are the complicated femininities from which I and my work proceed.

Oh, and I came to Chicago to attend grad school.

What have you been listening to lately?

My main lady is 12th century abbess, mystic, and choral composer Hildegard von Bingen. I listen to performances of her work and fall out of linear time.

I’ve also been listening to audio recordings of Sarah Waters’ novels.

And there’s Kate Bush, Lana Del Rey, Enya, Lizzo, Tina Turner, Peaches, and Cocteau Twins. I’ve recently been learning more about Sinéad O’Connor.

I’m eagerly awaiting a recording of the recently premiered Kevin Puts opera ‘The Hours.’

Much of your imagery brings to mind queerness and representations of femininity (ex: the flowers in The Women (Dita in Distress, 1999, Dir Christina Faust. starring Dita von Teese, 87 min). In what way, if any, do you locate yourself within these themes and how you present them through your work?

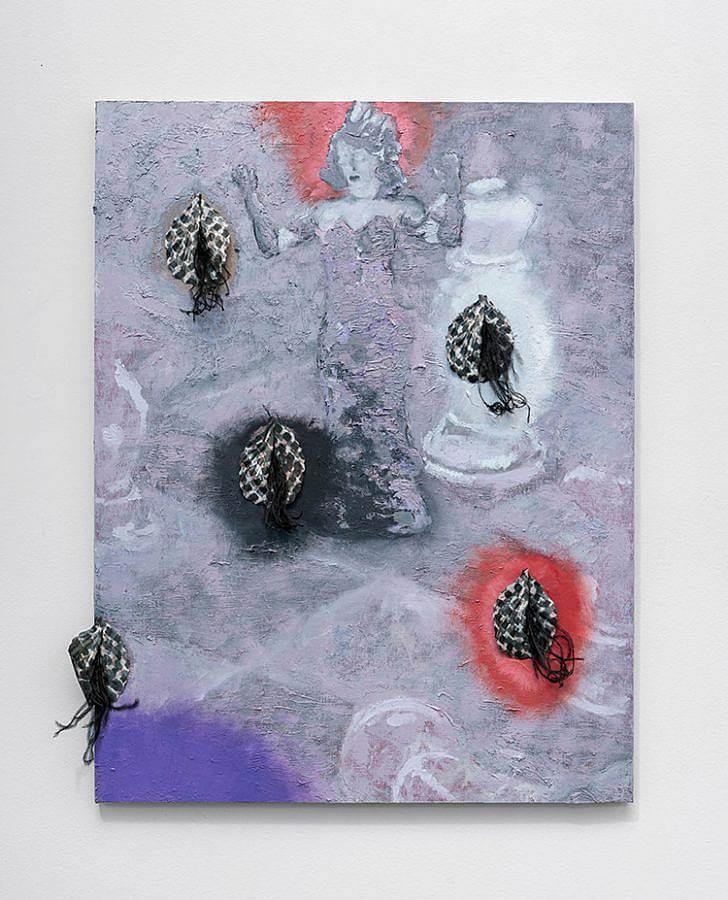

Of primary interest to me are the signals that have been projected to and fro around a position of femininity throughout history. I hold close the signs, conventions, and stylings that have been associated with the feminine even as they were separated from an ontological state of womanhood. I experience the feminine as a moving target. I see my work within the lineage of écriture féminine, with Hélène Cixous, Bracha Ettinger, Vaginal Davis, Jane Gallop, Joan Copjec, Clarice Lispector, Marguerite Duras, and Virginia Woolf as models for ways of being and making. At close range too are Lacan, Genet, Fassbinder, Winnicott, John Waters, and a litany of drag artists who themselves are oriented toward transgressive femininities as a central design in their self definitions of queerness, or, more broadly, desire.

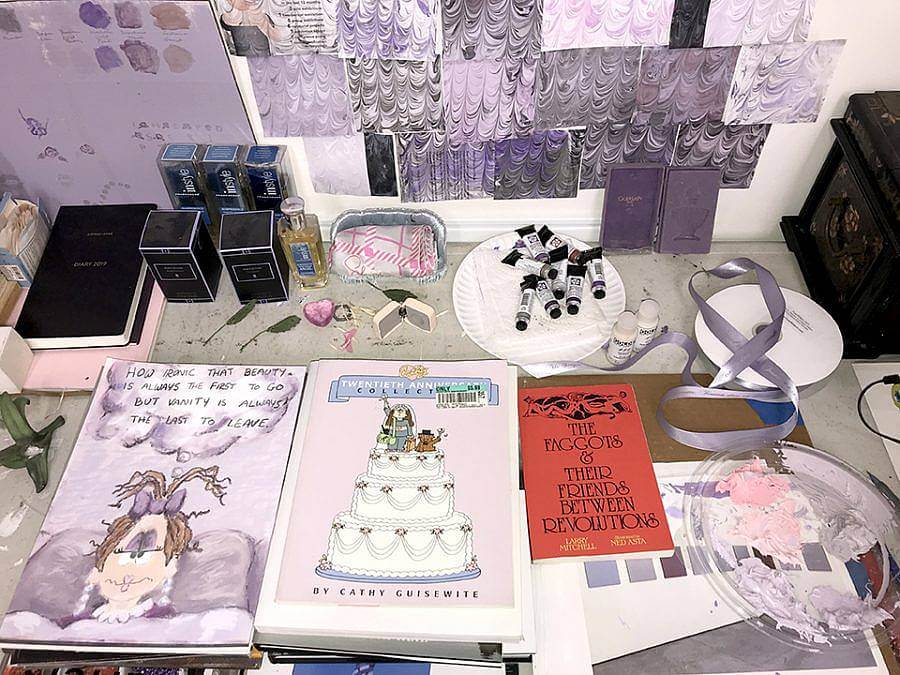

Things like silk ribbon, perfume, cosmetics, artificial flowers, fashion plates, pearl necklaces, millinery, and erotic writing are lively material and philosophical forms through which I may sublimate my aspirations for a femme that is testily free floating, or as Baudrillard asserts, does not compliment masculinity within a binary but rather challenges and disrupts gendered binaries that would seek to contain and control it. A femininity that is eccentric and expansive.

Queerness for me has come to signal dis-orientation rather than a range of alternative orientations. This is closely associated to a kind of anarchy in the commons as well as the strategic refusals José Esteban Muñoz calls ‘disidentification’. My queerness is excess. My queerness is jouissance.

What is your favorite studio snack?

I keep a bottle of Balvenie 12 Year Doublewood Single Malt Scotch in my studio, and after getting to know perfumer and genius polymath Laurie Stern who uses ‘bonbon’ as every part of speech—verb, adjective, noun—I’ve relished keeping strawberry crème bonbons around for an occasional indulgence.

Your work features a very broad range of materials and techniques, how do you feel toward having such a holistic approach to making?

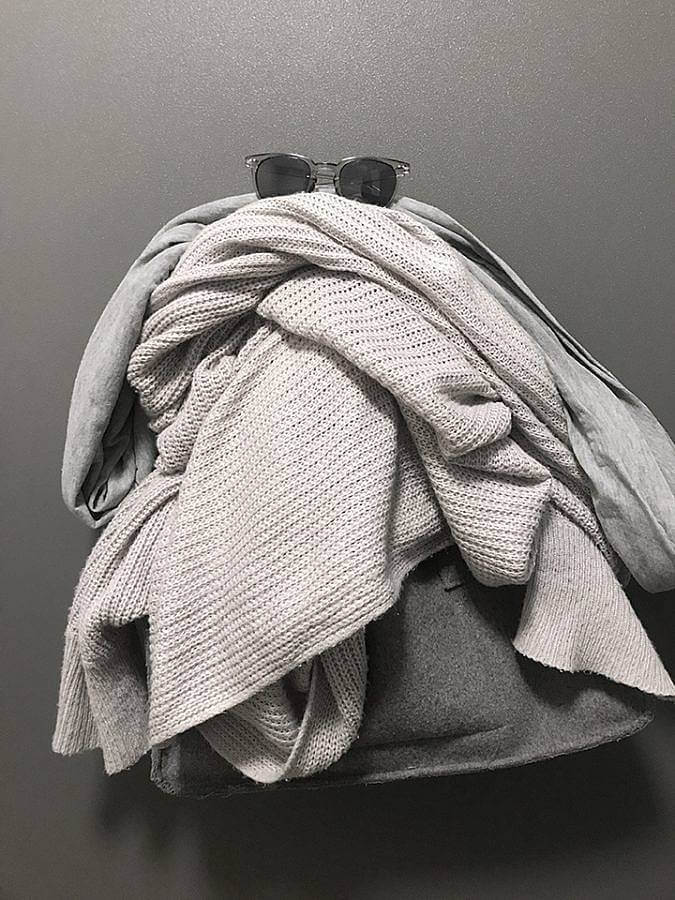

Ha, you say holistic; I say promiscuous, and in aligning the two terms, something queer happens around the proliferation of multiple media, what constitutes ‘wholeness,’ and the advancement of a decidedly non-monogamous ideal. If I’m anything, it’s a materialist with deeply psychoanalytic inflections. As such, I’m primarily concerned with the material world from which I am constituted, the means of production that cut across it, and most of all the compelling tensions that arise from desire and pleasure as they’re mapped across material encounters. Seduction, fetishistic longing, cosmetic artifice—these are guiding principles. I want to touch these things, and I want you to want to touch them. Powdery, velvety, slippery, shiny, iridescent, absorbent, crumbling, shimmering, the betraying artifacts comprising a patina of history. I float amongst these possibilities.

Can you talk about your curatorial practice and how it relates to your studio practice?

In my art practice, handmade objects are often complimented by found or appropriated things that are fitted into the conceit at hand. This instinct for using what is already available combined with a magpie-like drive to collect I inherited from my paternal grandmother and father conspire to recommend curating as an obvious mode of creative production for me. Which is to say that my curating is very close to my studio practice and as such asks for a great deal of trust from the artists with whom I work.

Along with straightforward exhibitions that I’ve curated in all kinds of institutions, there are also projects like Township of Pride, Advanced Potions, and Splitsville Smells Like Irises wherein artworks or exhibitions ostensibly “by Matt Morris” contain guest appearances from other artworks or historical artifacts. I didn’t invent this method of working: I’m inspired by folks like Fred Wilson, Willem de Rooij, Gaylen Gerber, and Walid Raad.

In the past three years, my studio has directly adjoined RUSCHWOMAN, a sister satellite space to my partner’s gallery Ruschman. I offer support for RUSCHWOMAN’s programming when I’m able, and the best of times is when art I love, obsess over, dream about, is on view just a few steps away from where I make my art.

What are some exhibition spaces or arts organizers that you feel inspired by?

Michelle Grabner is my pal, my colleague, (uh, sortof my boss as she’s the current Chair of Painting & Drawing at SAIC), and a cherished role model. The Suburban that she’s run for something like 25 YEARS with Brad Killam is grassroots generosity at its best.

There is perhaps no other curator alive who’s done more to challenge, reframe, and disorient held notions of self and identity vis-a-vis contemporary art models than Thelma Golden. No question. I’m also devoted to the sensitivity, incisiveness, and experimental risk taking that appears in projects organized by Risa Puleo, Legacy Russell, and Ruslana Lichtzier. Shelly Bancroft and Peter Nesbett who are Triple Candie are enviably smart, irreverent, and timely in their critique-as-curation stylings.

My favorite museums to visit are the Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst in Antwerp, the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The National Museum of Mexican Art is one of the most vital, wise, hearty institutions I’ve ever encountered. Chicago should not take it for granted; it’s extraordinary.

Gallery programs I super admire, have loved working with, or WOULD love to work with are Bureau, High Art Paris, Richard Saltoun, CASSTL, Andrew Kreps, Essex Street, Ballroom Projects, Shimmer Rotterdam, Office Baroque, bombon projects, New Discretions, Rodolphe Janssen, Balice Hertling, Tatjana Pieters, Mrs., The Valley Taos, Sweetwater, and Pangée.

And of course I’m biased, but I’m rarely disappointed by the passion and smarts my partner Eric brings to his gallery Ruschman.

How did you become interested in fragrance?

Toward the end of college I would incorporate broken bottles of perfume into installations, sometimes with other more putrid smells like burnt feathers and hair. At the time, I was steeped in French art and cultural histories, perfume’s uses in the courts, as part of the apothecary guild, and the ways painting, perfume, and fashion were instrumentalized as expressions of radical social shifts and regime changes.

This led to my ongoing project sillage, wherein I invite museum or gallery staff to wear a fragrance of my choosing, and eventually to a self-taught aromachemistry practice of formulating perfumes.

Since my dad died in 2018, I’ve also come to see his collection and wearing of modestly priced fragrances as a formative early exposure to the non-visible ways perfume interacts with expressions of identity.

What is something that you want to see more of in contemporary art?

I want to see more transgression, more risk taking, more absolute divestment from normativities, more fat, more femme, more of Audre Lorde’s erotics and anger.

While the past ten years has seen some improvement in the representation of marginalized peoples in our field, there’s an unfortunate demand for many artists of color to make work ‘about their identities’ in order to receive recognition. I want to see more loving embrace of the unique personal visions of what artists really want to make rather than being pressured into reinforcing really brittle notions of self, race, etc. I want to see more unqualified support for a diverse population of artists on their own terms.

I want to see more inclusion of neurodivergent or otherwise disabled artists into mainstream discourses, markets, collections, and modes of visibility. The world we live in was brutally constructed in ways that privilege only a narrow segment of our society’s physical and cognitive abilities, with broader forms of intelligence and expression categorically suppressed and dismissed. I want to see those value systems reordered to not only recognize but treasure and celebrate the insights that come from divergent vantages and lived experiences.

I want to see collectors and institutions continue to support women and femme artists as they get older, rather than selecting a few token women and otherwise erasing the voices and contributions of older women from discourse.

And as in my own practice, I believe we would see worlds of good if more people opted to process rather than repress.

Many of your motifs incorporate vintage designs and feelings of antiquity, with references to Dita Von Teese amongst others. Where do you source your design inspiration from and what does this imagery represent to you?

I suppose I’m traumatized by how unprocessed our histories are—the opposite of nostalgic. I need to deconstruct how we got to, say, the United States positioning itself as a world superpower and an arts and cultural epicenter following the World Wars: how 450 years of slavery, its abolition, the Industrial Revolution’s rush to compensate for that lost workforce, the advent of mass produced commodities, colonial throes, and decimating bombs have conspired to forcibly couple widespread suffering with a notion of success via nationalism that has been afforded only to the most centralized public faces of a white supremacist, heterosexist, misogynist cultural economy. And all the while, notions of sexuality, gender, fashion, taste, and beauty have evolved coextensively with these violences, politics, and power relations that have given form to the world as we encounter it.

I make my home in libraries. One forensic lead gives way to another. The quality of my questions is measured by their potential to produce even more interesting questions. Popular culture, burlesque, queer subcultures, fashion, advertising, film, and modern and contemporary art provide touchstones from which an analysis of these histories may be developed.

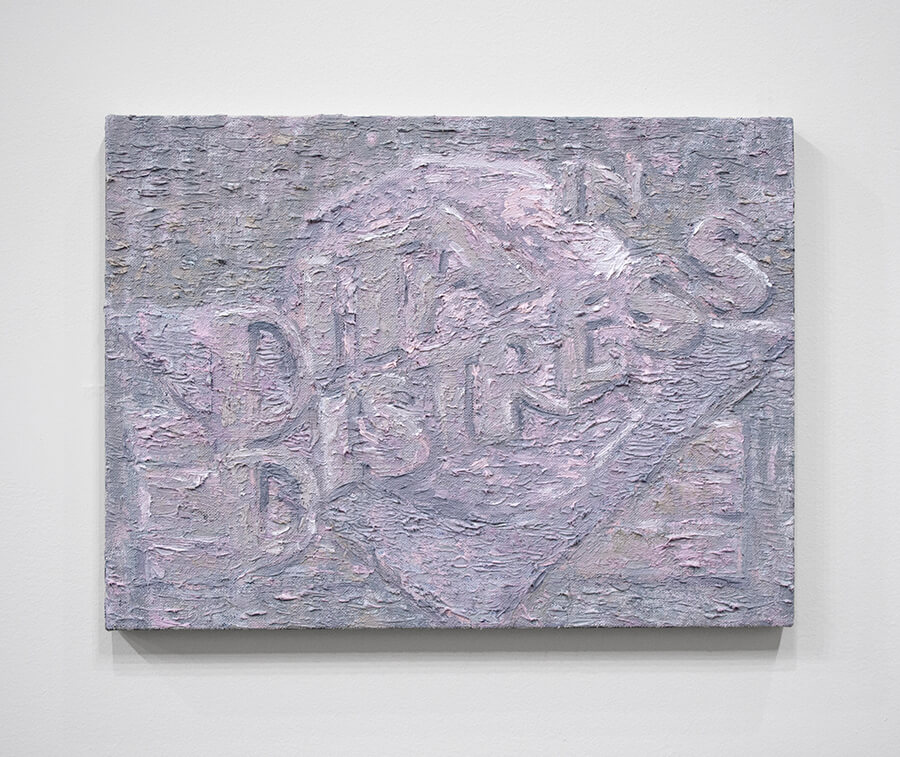

The pastel color palette is very consistent throughout your work, what influenced your commitment to it?

These rosy tints and ashen, greyed out hues have been around a while. When my parents got two of everything after being told to expect twins, they surrounded Michael with light blue things and me with pale pink ones. My favorite color at six was ‘storm cloud gray.’ And so it goes—I have intense emotional responses to the palettes of Rococo painters like Watteau and Boucher; the wan, girlish color schemes of Marie Laurencin or Sofia Coppola; the white-and-pink wax confections Petah Coyne was making in the early 90s; the icy roses and ‘griege’ Christian Dior introduced to fashion after WWII.

The mauves and pinks and violets and greys I use lack the enthusiasm of, say, Easter pastels or baby nursery décor. I tint and I desaturate. It creates some critical distance and gives form to an ever present melancholy.

Do you have any daily rituals?

If not rituals per se, I have a daily habit of focusing on and articulating sources for gratitude; if I’m in Chicago I love on my two grey cats; I drink an alarming amount of Diet Coke.

‘’Camp’’ is a word that gets thrown around a lot recently. Would you use this term in any way to describe your work?

I absolutely would, but in doing so commit Sontag’s crime: “To talk about Camp is therefore to betray it.” I mince deftly in and out of an observant, critical posture toward a state that is more or less totally oblivious, un-self-conscious in my yearnings and affectations. My ethics is camp, and far from its use as a cultural shorthand for frivolity, I believe that today camp is an indispensable capacity within political rupture with which to refuse tactics and tonalities that mirror the far right within the liberal progressive left.

At the time that Andrew Bolton curated the Met’s fashion survey ‘Camp: Notes on Fashion,’ he paraphrased Richard Dyer to say that camp “should be a clenched fist on a limp wrist.” That’s a decent way of considering camp in the context of my work. I have a preference for irony that nonetheless holds space for earnestness bound up in it. My mom once told me that I’m “irreverent about the things I’m most reverent about.” If we are within culture, if we are using language, if we have placed any qualifiers upon our empirical experience, then we are operating within realms of artifice—and that’s pleasurable and exciting, and camp maintains perspective on all these simulated, synthetic, fanciful fictions. Pleasurable because one’s whole life has been spent struggling to confirm the presence of some queer aberration exceptional in contrast to a supposed norm, something natural or at least naturalized. Camp unlaces all of those presuppositions. Not only does it resist the reification of centralized, monolithic ideologies, but it also celebrates the meaningful potential of deceptions, illusions, fantasies, bawdiness, stupid jokes, and a pointed silliness in the order of a court jester.

One of my all time favorite treatments of camp was what Céline Dion told reporters at the 2019 Met Gala: “At first I was a little bit confused when I heard ‘camp’… I wasn’t sure what it meant… Luxurious and antique and, like, timeless and… all those feathers… and all that you see right now, for us, was camp.” I sometimes reminisce over the extent of that incomprehension, leaving the ordering principles of language.

Any upcoming projects you are excited about?

Well I want to say that among other goings on, I have an abiding love of the questionnaire as a form, and I’m a devoted reader of LVL3’s artist series. It’s a really big deal to get to do this with y’all. Really, thank you so much.

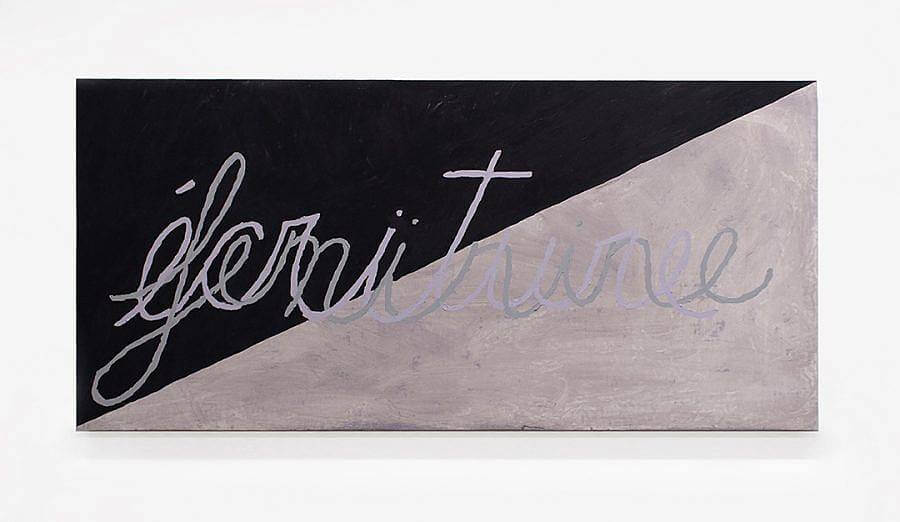

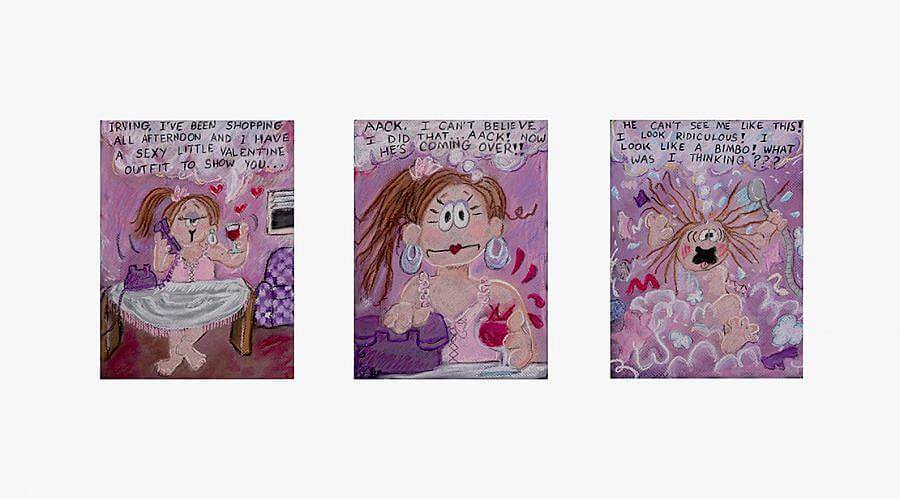

I’m feeling very gratified about some new shifts in the studio. Along with the ongoing works based respectively on paintings by Sherrie Levine, comic strips by Cathy Guisewite, and surrealist photographs by a range of mid-century women, I’m in the middle of developing new pieces based on “female” monsters from the various Power Ranger TV show franchises and a group of six new perfumes inspired by women in literature and mythology.

I have a group of new works on the Zwirner-powered Platform right now. I’m looking forward to showing several new paintings in my ongoing Sherrie Levine project in Milk and Eggs, curated by Andrew Falkowski at Color Club in Irving Park which will be up during Expo. I’ll also be included in Amuleto, organized by Edra Soto, Alberto Aguilar, and Madeline Aguilar at the Hyde Park Art Center (April 22–August 13). The INIMITABLE wonder that is Aay Preston Myint will be showing new works of mine at San Francisco’s slash gallery this summer.

Interview conducted and edited by Sam Dybeck and Ben Herbert.