Tell us a little bit about yourself, your company, and describe your practice.

S: I have a background in International Business and Enzo has a background in Visual Arts.

We were born on an island in Campeche, in southeastern Mexico. Our father is an architect and our mother dedicated herself to wildlife photography for a time; so we were introduced to aesthetic awareness from an early point in our lives.

Lørdag & Søndag is a design studio based in Mexico City that works closely with master artisans from different regions of the country. For our pieces we mostly use a variety of natural fibers, but also other materials such as volcanic rock, wood, marble, and leather.

What is the origin of the name Lørdag & Søndag?

S: It is Danish for Saturday and Sunday. At first, it was a way to show admiration for Scandinavian design. The scope has changed a bit, but we have not lost the attention to detail or our taste for simple shapes.

Who are some of your favorite artists?

E: I couldn’t say that I have a lifelong favorite artist. My interests are seasonal, so to speak. Now I am researching what I call “lithic modernism”: the cromlech-like shapes of Yves Tanguy and the buttes from Max Ernst´s Arizona period. Which I think is very timely: Lately there has been a return of modern art from the first half of the 20th century into the field of design.

S: I really like Georgia O’Keeffe’s color palette and sense of volume.

Now that I think of it, we unintentionally concurred on the American Southwest theme. Maybe it makes sense because many parts of the Southwest was once part of Mexico. The interaction between Spanish and indigenous cultural elements is very present there as well.

Pedro Reyes is also a contemporary Mexican artist that we greatly admire, on a formal level.

What/who is influencing your work right now?

E: We have been getting closer to pre-Columbian art. This is not just a statement on identity or nationalism. Deep down, it is the origin of a large part of the practices of the artisans with whom we work. The National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City is a great source of inspiration.

We also take many references from 20th-century artists who knew how to integrate pre-Columbian shapes into a more modernist language, such as Vicente Rojo and Carlos Mérida. Both were very influential in the consolidation of modern Mexican art, even if one was born in Spain and the other was Guatemalan.

What is one of the bigger challenges you and/or other artists are struggling with these days and how do you see it developing?

E: I think that making things that are original and feel honest is a big challenge when it seems like we’re all exposed to basically the same images on social media (Pinterest, Instagram, etc)

We also live in a time where there is an industry designed to keep us in a state of constant distraction and I think that is a big obstacle for creatives who want to focus on their work in a deeper way.

S: – Because of mass production, people are not used to paying for the real value of handmade items. This sadly also happens in our country, where there is such a rich artisan tradition.

What are some recent, upcoming, or current projects you are working on?

S: We are very excited because next year we will be at XTANT, a fair in Mallorca specializing in textile design.

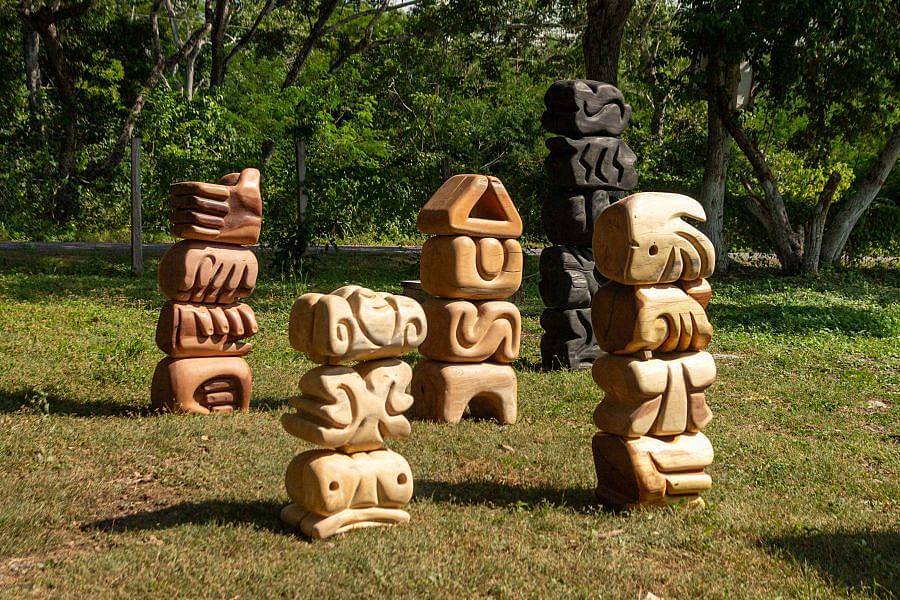

This month we just presented some sculptures inspired by Mayan stelae in Campeche, our home state. It was a collaboration with Xoxot, a project that works with wood rescued from the construction of the Tren Maya, a project for a new train line that will cross the Yucatan Peninsula.

We are also about to release our collaboration with Japanese artist Anri Okada: a series of sculptures and molcajetes (Mexican mortar and pestle) sculpted in volcanic stone and intervened by her.

How has your process evolved in the last few years and what does it look like currently?

S: Mexico City is one of the largest cities in the world. Logically, we are under a more Westernized, more industrialized scheme of what it means to be “productive.”

Many artisans belong to indigenous communities. The pace of life in their towns is different. Their priorities are different.

It is common for us, for example, to tell a customer that their order will be delayed because the delivery date would be close to an important celebration in the artisan’s town, such as the Day of the Dead or the festival for the town’s Patron Saint.

By working with artisans we have learned that we must be aware of their working conditions and their cultural context. Working closely with them means respecting their culture and lifestyle.

What was your earliest introduction to art that reinforced your curiosity to create?

E: I knew that I wanted to dedicate myself to art from two events: seeing Hyeronismus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights at the Prado Museum, in Madrid, and exploring the architecture of the videogame Final Fantasy X on PS2.

S:In our parents’ home there is a large collection of crafts and curiosities brought back from their travels. We grew up with the notion that a house could be full of beautiful objects with interesting stories.

How would you describe your work to a stranger?

S: Sober yet playful, organic, and artisanal.

How are materials considered to inform the final shape each piece takes?

E: Mexico is a country with a great artisanal legacy that varies greatly depending on the region. Many artisans we work with proudly come from a long family tradition. However, what this tradition implies is that they are accustomed to repeating certain patterns and working with a catalog of pre-established forms.

When we make the proposal to work with a new artisan we try not to “scare them away” by showing them a piece that is too complicated or “avant-garde.”

Sometimes, especially the first few times, there is a gap between our design and the final result. We try to see this as part of the process and also give the craftsman some creative freedom to solve the piece according to their knowledge. We are always very open to hearing feedback from them.

In the end, those solutions enrich the pieces. After all, tradition is also a form of wisdom or experience that is passed from generation to generation.

Interview conducted and edited by Wonu Balogun