Tell us a bit about yourself and what you do.

I’m an artist who works with/in texts and textiles. I am currently pursuing a graduate degree in Performance Studies at Tisch, and to pay my bills, I work as a communications coordinator for the Zine Union Catalog through NYU’s division of libraries and am an editor for an encyclopedia on world textiles to be published by Bloomsbury in 2023. It’s always difficult to try and talk about myself and what I do, because how do I bring in all the peripheral stuff that keeps me alive? I’m not so sure.

How did you get started as an artist and writer?

I think as a teenager I gravitated towards fiber arts, first through fashion and then through painting and sculpture. I first learned how to use a sewing machine in my home economics class in middle school, and from there, I began altering my clothing and sewing my own garments. My interest in soft and malleable materials continued to develop while I was in college. And after a couple of years of working in special education and food service, I decided to pursue an MFA in Fiber and Material Studies, and that’s also when I really began to use text as another affective material.

This was nearly five years ago now, and since then, I think both writing and weaving have been both a consistent and immediate form of expression for me; they fall into a sort of rhythm that comes along with… having to hustle, unfortunately. These are practices that I can pick up on the train, in a spare half hour here and there. I do deeply crave those expansive days of working in a studio, and I regret not prioritizing more time for meandering moments of play, but I haven’t been able to juggle it all, so this is what my art practice has grown into, a kind of testament to everyday life.

How do you approach collaboration as an artist?

I feel like everything is collaborative to a certain extent. My thoughts and ideas are not conceived in a vacuum on my own but are so strongly influenced by those around me, those that I read and admire. I’m always responding to something, whether that be a person or situation or memory or feeling. But maybe to answer the question more concretely, I do love collaborating with other people, be they other artists, writers, or scientists. Sometimes it comes together in collaborative work and other times, the artwork develops over the course of various conversations, and I weave together elements that my collaborators send me, such as in water baby: a shared well for Allie, Shacoya, and our mothers. Everyone offers their own perspectives and finding moments of resonance between fields can forge new unexpected paths, possibilities to rethink a question.

Introduce us to your perspective on haptics, and the role of Labor in your work.

I think my attraction to the haptic comes from this desire to explore other modalities of understanding, of making sense. I’m very much influenced by Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology, in which she considers the orientation of lived experiences and asks “to what extent does philosophy depend on the concealment of domestic labor and of the labor time that it takes to reproduce the very ‘materials’ of home?” By working through fiber arts, I want to underscore both the tactile materiality of my works as well as the orientation from which they were produced. They were woven, assembled in an attempt to make sense of these fragmented parts of my life, my life also is but a fragment of a larger story of diasporic perseverance. I am also thinking of Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s “hapticality,” this move towards “the capacity to feel others, for others to feel through you, for you to feel them feeling you.” What happens in this space of intimacy has profound political reverberations, and an attunement to touch, our senses, can embolden these connections.

What process do you undergo to dye the fibers you use?

I have a pretty piece-by-piece, day-by-day process, so what that means is I’ll cook with onions and start to store the skins in a yogurt container in the fridge until I’ve amassed enough to dye threads with. I like to use onion skins because the mordant which fixes the color to the fiber is already present in the tannins. But then sometimes, I just welcome total chaos, since the goal is not to arrive at archival stability — I’ll toss wilting bouquets in the dye pot and see what colors the bluebells yield after an hour or two of simmering on the kitchen stovetop. It’s very… loose and improvisational. It becomes a way for me to incorporate bits and pieces of everyday life into the process of artistic production. Of course, sometimes I’ll use Rit dye too, if I’m experimenting with ikat and trying to achieve variation in the color of my threads, to create a sense of depth in the weavings.

What role does performance play in your work?

I think I’m still figuring it out. I sometimes will do readings, and that is a kind of performance, but what brought me to this field of study is the kind of attention that is given to embodied knowledge and other ways of understanding that have been neglected within or intentionally erased by Euro-American hegemonic structures of thought. I’m interested in the performances of everyday life, what they reveal, the kinds of resistance they enact, or the dreams they materialize. Weaving is such a practice for me.

Tell us about your journey with the Atayal loom and its significance to your practice.

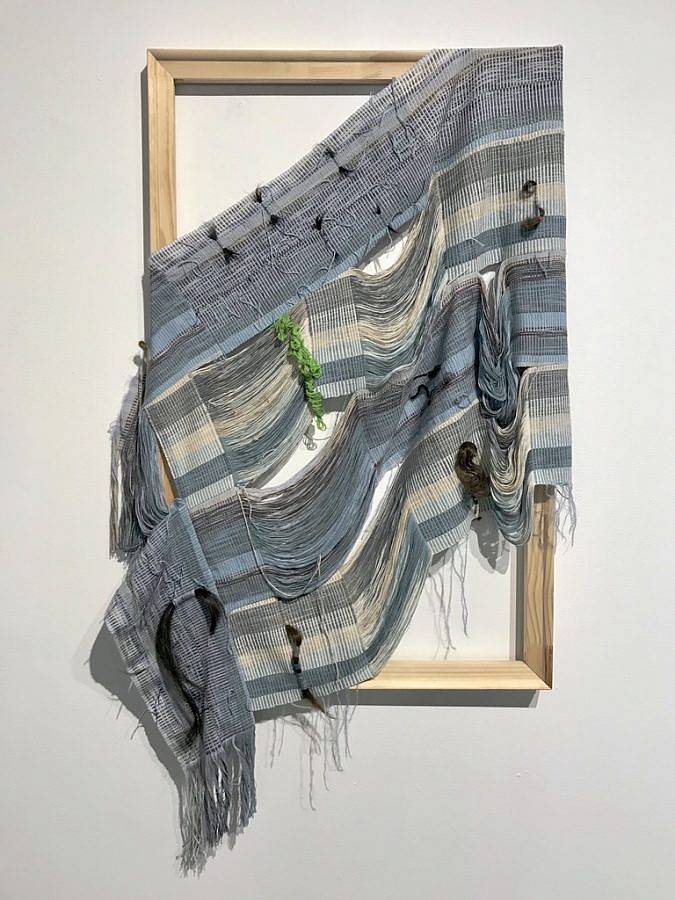

I feel extremely grateful for the year that I spent in Taiwan apprenticing with an Atayal weaver named Sayun. In 2017, I received a Fulbright Research Fellowship, which gave me the opportunity to work with the Ethnology Department at National Chengchi University, and the faculty there connected me with Sayun. From her, I learned how to weave traditional patterns on the backstrap (also called foot) loom. This particular loom has become my primary tool over the years. Though I was educated on floor looms, tapestry, and frame looms, the indigenous Taiwanese loom is what I keep returning to. I think there is something beautiful about the way the textile completes itself in a loop, which is unlike the aforementioned looms that have a distinct beginning and end. This loom requires specific coordination of my body, a rhythmic synchronization that has provided a sense of grounding (metaphorically and literally, as I sit on the floor) throughout these last few difficult years.

How do you mean to weave words and fabric with one another?

In past works, I have woven texts into fabrics or embossed them onto paper, leather scraps, which then made their way into my weavings. At the moment, in the current weaving I am working on I try to highlight the absence of words or the ways in which they falter. I think of my relationship between writing and weaving as living alongside one another – I’m not sure how, when, if they will intertwine. I think I’m still trying to develop a language for their cohabitation.

How do you respond to a site or place?

In the past, I chose to work with pre-existing features, the holes, and scuffs in a space, to draw attention to minor details that individuate a place, as opposed to cooperating with the anonymous illusion of a white cube. I remember a critique while in art school, when Hamza Walker mentioned that there was a sort of democracy to the spread, in the way that handmade clay, paper, and woven pieces proliferated the installation. I remember other students wanting maybe a focal point, an object with which to attend to, like the subject of a painting, and I didn’t have the words then to describe why I resisted that.

I think I’m finally understanding my inclination to resist landing or arriving at one conclusion or establishing some hierarchical order. The idea is to attend to the margins, the periphery as much as possible. Though my work is most often shown in traditional gallery spaces, the underlying method of installation is still usually directed by the site. These last few years, due to the parameters of having a home studio, I have started to make more self-contained works that can be easily hung on the wall. but I think compositionally, the underlying desire remains the same.

What role does belonging play in your work?

I recently read A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging by Dionne Brand, where Brand so eloquently navigates the questions of identity without ever using the word. Instead, she seems to explore ideas of identity through this longing for belonging. I think there is a similar interest on my part to not get caught in the webs of identity politics, of superficial quota-filling tendencies without getting to something deeper. Maybe belonging is a way to think about our interconnection, the communities we create. In terms of my artworks, I think there is this concerted effort to bring everything in, to have everything belong and share space – all sources of shame, sentimentality, and survival are chaotically yet carefully, intentionally included. Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings and Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings are influential here.

What are you listening to?

Last night I was preparing a warp while listening to Audre Lorde reading “Uses of the Erotic,” but I feel like my responses are heavily influenced by the program I’m in currently. I like listening to podcasts like David Chang’s on food, Feeling Asian, On Being. While writing recently, Andrew Bird’s Echolocations: Rivers has been on repeat.

How has your shift from Chicago to New York impacted your practice?

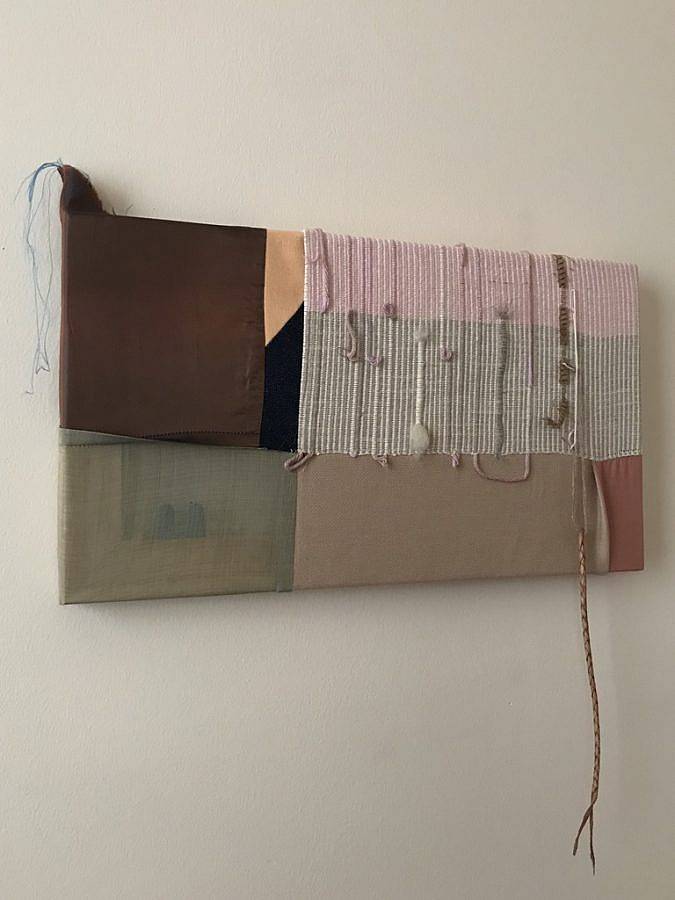

My relationship to writing and critical thinking is definitely being shaped. I’m not sure that I have the words to describe that development just yet, but I’m very thankful for the opportunity to challenge myself in this way. I also have no idea what’s going on – maybe a more general trend in the art world, but I am finding myself becoming re-enamored with painting. Maybe it’s just stumbling into galleries featuring painters I remember looking up to while in undergrad, like Dianna Molzan, or Jennifer Packer’s current show at the Whitney. But I am surprisingly seduced by the material, the layering and scratching away, the evocative accumulation of pigment that produces a shadow of an image.

Upcoming Projects?

I’m still tinkering with cyanotypes, using what little sun we have left before the gloomy winter really sets in. My friend Kioto Aoki gifted me with more chemicals before I moved from Chicago to New York, so I’ve been playing with making cyanotypes on painted and stitched canvas as well as on woven scraps. I’m also weaving what I am interpreting as lined paper for children learning to write, the ones with dashes running down the center, except at times, I am picking up the dashes while weaving, so that the line falls away, begins to droop, making coherent calligraphy impossible. The warp consists of ramie and cotton, while the weft is a great fuzzy mohair, so the cloth, while white, is quite textural. These are just some in-progress projects I pick up when my brain can no longer process verbally (ie. in reading and writing) and I need to exercise another kind of language or knowledge.

Interview composed and edited by Joan Roach.