Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

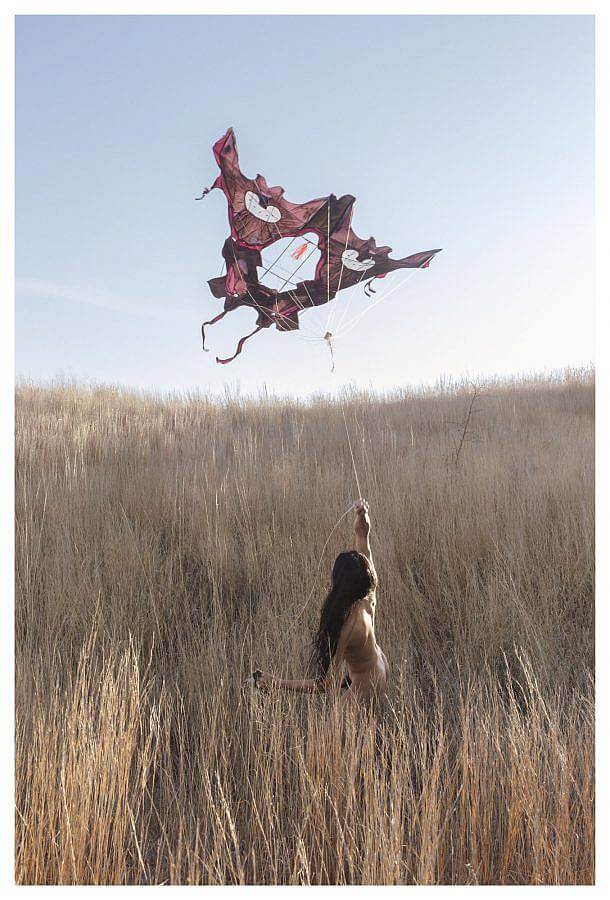

My one-sentence elevator pitch these days is that I make and fly kites and sometimes you can wear them too. Maybe appropriately, I’m based in the Windy City, though I find myself drifting and traveling quite frequently these days.

Could you describe your practice as well as a bit of your process?

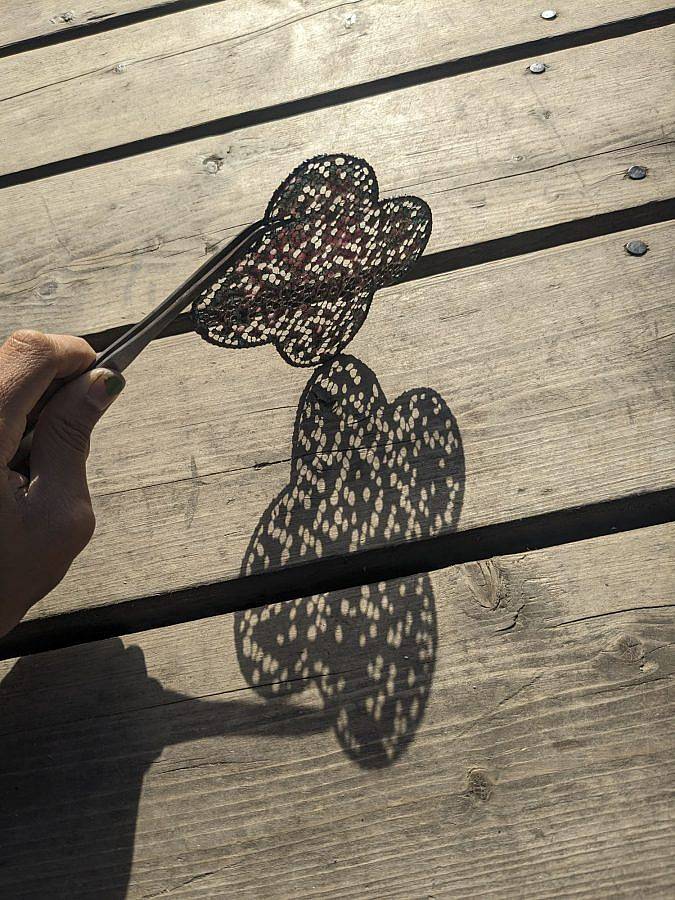

Kites are just one facet of my work, albeit the one I seem to be most known for currently. I work fairly interdisciplinarily across sculpture, drawing, sound, performance, writing, and installation. Conceptually, my process typically begins with picking one subject of interest such as collars, backscratchers, birds, bats, et cetera, and then building out a web of relations, words, stories, and objects that surround that subject. I joke that my most used tool is probably etymology.com. I love to learn where words come from, find adjacencies, and making objects speak to their own pasts. These new words and relations become permissions—excuses,really—for myself to explore new materials and techniques. I’m very much a hoarder of skills and love the feeling of newness that comes with being a constant amateur at things. It gets really exciting when techniques begin to merge, like learning how to make needle lace, or how to enamel jewelry and then trying to enamel metal lace.

Your work directly responds and exists within environment, playing with wind, sun, water, etc. How do you situate your work within this? What do these spaces(elements) hold for you?

For one, it’s just a way to escape the reliance on institutional spaces. I like to say that the sky is my favorite gallery to show in. But working with these elements for me is also usually a way to relinquish control. I don’t necessarily know when it will be a sunny day and I don’t necessarily know when the wind will be in my favor. It’s humbling and requires a reorienting of time and sense of control. It also just forces me to be outside more often!

As material, I love that these elements are simultaneously so enduring across all of time, but also so incredibly ephemeral. Like the way the sun is shining or the way the wind is blowing is very specific to the present moment, but these are elements my ancestors since time immemorial have responded to and elements that people will respond to until the end of time. It collapses time in a way.

What is influencing your work right now?

The most overwhelming influence on my work presently is what is happening in Palestine. It’s made me reconsider entirely what it means for the sky to be a space that is free and open for everyone, when all they see are bombs and destruction. Kiteflying has become such a symbol of hope and resistance as of late because of Refaat Alareer’s poem, If I Must Die, and the fact that the children in Gaza set the world record for the most kites ever flown simultaneously. It’s made me think so much about what role I can play as an artist and what flying a kite means in this moment. Free Palestine!

How do you define a kite? What does the kite mean for you?

I appreciate this question because I often find myself making kites and then wanting to call them anything but. It’s more interesting to say that I’m flying flowers, stars, clothing, bodies, what have you. I think many people are quick to assume it’s about a desire to fly, but I’m not trying to build an airplane. There’s something more interdependent about the kite that makes me feel like I’m actually having a conversation with the wind. To go back to the theme of time, I like that kites kind of evoke both a past and a future. They’re about hope and innocence and wishing and youthfulness. People that catch me flying often share anecdotes about the kites they flew when they grew up. The artist Tal Streeter wrote a sky art manifesto where he called them structures of aspiration and that has always stayed with me. In a sense, maybe that’s all of art; we’re all just reaching for something beyond us. Maybe my kites reach a little bit further.

As a multidisciplinary artist with a background in fashion/garment design, how do you let these differing practices inform each other? How do they let you grow as a maker? Do they exist as one for you?

I think my favorite way of working is to borrow or adopt the language of one discipline and use that as a lens to work through a different discipline. Fashion is maybe just my lens of choice at the moment. I love that clothing is so pervasive throughout all cultures and histories that I’m sure it will always be endlessly generative. I love to call anything clothing: shingles on a roof, protective tarps, clouds. It’s like purposely butting up two characters in a play and seeing what kind of dialogue emerges. As an example, I used to work as a book designer, so I could pose a similar question of only describing my garment work through the language of bookmaking. What would a page number be? Or a bookmark? Or a dust jacket? It’s already a jacket! It’s coincidences like this where two different language sets touch or blend into each other that I really jump on. Vocabularies feed into each other and things quickly expand from there.

What are some recent, upcoming or current projects you are working on?

Most recently, I produced my first public kite happening and sky installation, Send Them Their Flowers. I don’t know if I personally would call it a success because it felt so chaotic to me as it was happening, but I do think it was a beautiful thing to do, and I learned so much, and I know it was a really key step in how my practice will move forward. I’m hoping to have more of these performative sky events in the future! The kites I made for this event are all going to resettle in an installation for a solo show at FACILITY in Chicago along with other objects that I’m working on right at this moment! The show opens in late August and it’s loosely about birds, flowers, and the act of looking up.

A theme throughout your work is body in relation to ___ , often bringing up themes of diaspora as well with this. Can you talk a bit about these themes within your work and some of your findings/realizations while working within them?

I think I have to admit to myself that I am truly a diaspora artist through and through. You know, all those overused clichés about not quite belonging here, not quite belonging there, ultimately do ring true and resonate strongly in the work. And if you don’t belong anywhere, where do you go? For me, my answer to that has been the sky. I tie a lot of this to transness and being nonbinary as well in the sense that both are feelings of being unmoored too. In the way that diasporic identity is so much about a failure or approximation of one’s cultural heritage, being nonbinary is often about a failure to conform to gender. So I become very interested in how the body orients itself and the tools we use to parse these identities out. Language is definitely one of these ways, but also objects and definitely clothing. To me, transness is a kind of knowingness that the world is not fixed, that we have agency over our bodies and the way we exist. Clothing is often the first proxy for affecting change over that.

Do you have any daily rituals?

I try to make it a point to always go outside at some point in the day and look up. I recommend it!

What do you collect?

I’ve been working with feathers a lot recently, so I have been collecting those. My partner often brings a ziplock bag out when we’re walking because I’ll inevitably pick up a feather and need to put it somewhere. I never really intentionally go out looking for feathers; I like that they just present themselves to me.

What have you been listening to lately?

I’ve been playing a lot of contemporary classical stuff in the studio, but mostly, I have really enjoyed listening to the birds lately! Right now, I’m in the woods of New Hampshire and I am in love with the hermit thrushes here. They have the most beautiful song and I’m going to miss it so much. The cat birds are amusing as well. The grackles were my favorite when I was in Houston earlier this year. They’re like annoying little sirens, but I find it so charming.

Interview conducted and edited by Lily Szymanski.