Can you tell us a bit about yourself and what you do?

I am a sculptor whose work with objects extends into performance, writing, and public events. I’m focused on the lives of objects and our bodies’ relationships with them and with each other. As a person, I have had trouble finding a place in this world for my body, and I make my work as a way of building the world I want to be in. I live and work in New York, sixty miles north of New York City, where I lived for ten years after leaving Chicago where I got my graduate degrees at SAIC—an MFA in Fiber and Material Studies and an MA in Visual and Critical Studies (VCS). My studio consists of two equally sized rooms connected through an internal door. I use one side for concrete casting, wood tools, and other messy fabrication, and use the other side for looking at in-process and finished work, drawing, writing, and it’s where I keep my archive of books and other exhibition ephemera. I usually work six days a week and I prefer to work during the day and almost never go to the studio after dinner.

How did you get started as an artist, writer, and performer?

I got started as an artist by making dances as a teenager, which was an extension of my training as a ballet and modern dancer. I went to Hampshire College hoping to study choreography, but pretty early on was drawn to the conversation happening over in the studio art building. I’ve always enjoyed thinking too much about hard, probably unanswerable questions, which is what pushed me in that direction. I made dances that had more and more involved costumes and props until finally there were no performers and I realized I had started making sculpture. I also studied philosophy with the feminist philosopher Monique Roelofs as my mentor, who supported me in developing a practice that shifted between various disciplinary formats. I found a home for this way of making (with words, objects, language, and bodies) in the VCS department at SAIC, and then just carried on since then, following the topics and ways of making I’m interested in. I’ve made sculptures and performances, written essays and performance scripts, opened and curated a gallery, and organized events as The Center for Experimental Lectures.

How do you feel your work responds to or deals with desire?

My work definitely engages with desire, in a variety of ways. A desire to have a complex and rich relationship with the physical world, to intimately know the objects of my everyday life and take them seriously as agents. I desire to find ways of relating to and connecting with other people beyond the traditional forms of kinship, and I desire a world in which gender is not predictably linked to physical characteristics and is a creative and evolving part of our personhood. There is also desire in the invitation to touch that my sculptures extend, an erotics of surfaces, textures, shapes, and relations to the walls and floor. A sexuality that isn’t only directed at humans. And I think of making as a form of wanting—wanting things to be different and making them be so, even just in my little corner of the world.

In terms of intimacy, & more broadly, how does your recent project, Other People’s Houses, align with your previous work?

Other People’s Houses is in some ways different than most of my other work, insofar as it is a photographic project in the form of a book that uses found images. But the kind of yearning and intimacy with people and things that it engages is a direct extension of my sculptural and performance work. I am always trying to figure out how to look differently, and so there is something about engaging with the objects in other people’s houses when I’m supposed only be looking at their faces that feels very in line with my ongoing interest in the backs, bottoms, and interiors of objects, which my sculptures direct our attention to in a variety of ways. Further, Other People’s Houses is rooted in what I understand to be some of the feminist implications of what we have seen of each other’s domestic lives during the pandemic. There is a taking seriously the political implications of the objects of our everyday lives that extends throughout my practice. We are all situated in such different ways, engaging in usually invisible care-work, and I think it has been important to see each other in these contexts. I hope we don’t forget about this.

After reading some of your work, I understand you’ve responded to artists like Bruce Naumann and Scott Burton. What about their work are you drawn to? What other artists have influenced your practice?

Scott Burton has been important to me because of his exploration of what I would describe as “the politics of the chair”—an embrace of a position of supporting others, making public space, bottoming, and allowing his work to fade into its own functionality as seating. His work, which, in my opinion, is shamefully overlooked, flies in the face of an interpretation of Minimalism as apolitical and only for cis straight white men. He was thinking about formalism in a really different way that has been really useful for me. With Nauman, I’m especially excited about his sculptures from the 1960s and their relation to the built world and their implied useability, and in a general way, I admire the changes in his practice over the years in a way that refuses any simplistic reading of his interests. Other 20th century artists that are meaningful to me include Beverly Buchanan, James Lee Byars, Richard Artschwager, Fred Sandback, Louise Nevelson, Melvin Edwards, Isamu Noguchi, Adrian Piper, Simone Forti, Felix Gonzales Torres, John McCracken, Barbara Kasten, Diane Simpson, Mike Kelley, Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Anne Truitt, Franz Erhard Walther, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Clark, among many others. Reading artists’ writing and speaking in their own words has always supported and fueled my work. I feel like I am part of a family across time with all these people I’ve never met.

Can you talk about your solo exhibition, END OF DAY, at Hesse Flatow? How is it situated in your body of work?

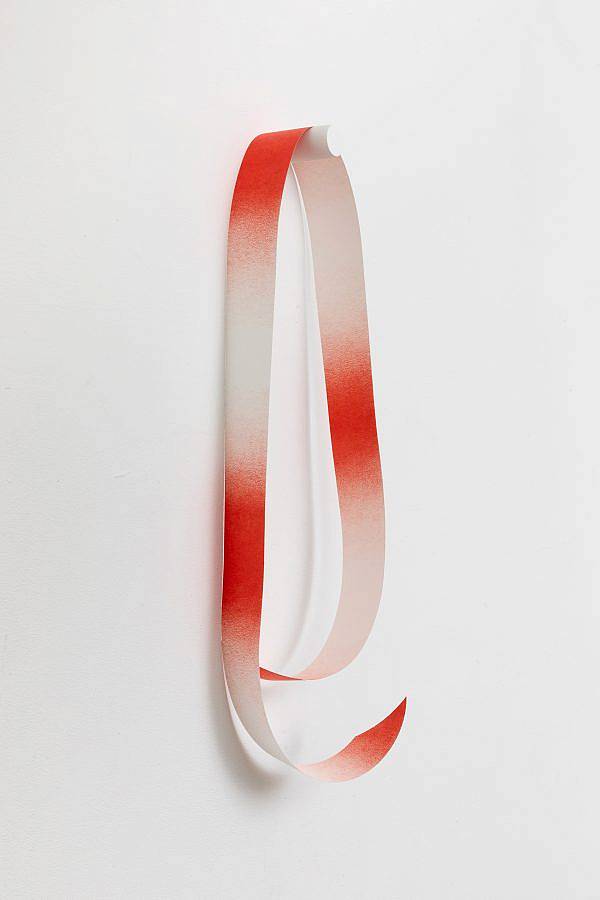

I made the 17 works in END OF DAY during the second half of 2020 and the first months of 2021, and at present, I feel enamored with them. The show is technically more complex, carefully made, more domestic, ornate, and maybe a little gayer than my previous shows. Making this show received my undivided attention in a way I’ve never experienced before. It has new ways of working in metal and paper alongside my concrete and wood and fabric pieces, and it feels exciting to add these new elements to my sculptural language. There’s a wood clothes valet shining all over with sanded steel nailheads, a brass cast of a wood shim made for “The Number of Inches Between Them,” a hand-dyed fabric work that feels like the folded contents of a linen closet, a polka-dotted corner chair, a stool the shape of an uppercase U, an elongated Shaker chair back that leans against the wall, a paper bathrobe sash hanging on a peg, a colored pencil on vellum outline of the seams and pockets of a pair of jeans on the floor, a cast concrete bench that looks like draped fabric, two cast concrete closed boxes, more. The works are installed in three adjacent rooms and speak to each other across the generous space between them. I love thinking about them there when the gallery is closed and there is no one to look at them but each other. I’ve commissioned 500-word responses to the 16 sculptures in the show from a range of people from my various art worlds, who will read these responses at an online event next week, after which the texts will be made into a catalog for the show. So I feel excited about this too—that the objects are generating something that comes out of all these people I admire, something beyond what I intended for them.

What are you reading right now?

Honestly? A novel for the book club I joined with my mom, sister, and two cousins. Jack Whitten’s journal “Notes from the Woodshed,” a new anthology edited by Gail Weiss, Ann Murphy, and Gayle Salamon called “50 Concepts for a Critical Phenomenology” and Harry Dodge’s “My Meteorite.” Don’t judge – I like reading several books at once so I can read the one that suits my mood. It takes me a long time to finish them!

How have you been navigating your practice amidst Covid-19?

I have some mixed feelings about saying this but have found the quiet, slowness, and grief of COVID to be a generative environment for my work. Many of the questions I am interested in around bodily vulnerability, care-taking, loss, the domestic, and our relationships with objects and furniture have been central during this time. I have also spent the time that was freed up by so many things in my life being canceled or postponed due to the pandemic to spend almost every day at the studio making the work for my current show, END OF DAY, as well as my book, Other People’s Houses, and my billboard for For Freedoms, What Held Your Body? My sculptures, in particular, request a slow, quiet, solitary kind of looking, which during normal life is hard to find, and now feels abundant. Generally speaking, I have always lived with a constant vague sense that something is very wrong, and so though I hate to admit it, I have felt pretty at home in the unease of this altered world.

In Sarah Ahmed’s text, Queer Phenomenology she says, “ Queer would become a matter of how one approaches the object that slips away, a way to inhabit the world at the point at which things fleet.” How do you feel your work inhabits this space?

As Ahmed so beautifully describes, we are oriented towards the world in many different ways, and some orientations we learn early on to be the “right” ones, and others to be wrong, askew, queer, or unrecognizable. One of the central questions I’m trying to answer by doing my work is the question of how we can transform our perception so that we see differently than the normative ways we have been taught. How can we notice different things, categorize the world and one another differently, be able to see people and things that are not immediately readable and nameable? How can we re-orient ourselves? I am chasing a way of looking that often slips away, overpowered by the structures already in place. So I think it would be right to say that my work is grasping at something that is always fleeting and that I am trying to bring into being in the spaces created by my sculptures and performances. I feel this to very much be true in terms of my own relationships with these objects –I make them out of a glimpse of something that feels vital and necessary, trying to make an orientation I can use.

In some cases, when something becomes too heavy to carry on your own, you rely on others to create and cast your objects. Can you talk about the solo and collaborative aspects of your making process?

A cubic foot of concrete weighs 130 pounds, and so many of my sculptures quickly become too heavy for me to maneuver by myself, even at their un-monumental scale. I find that this weight puts me in a relationship of reliance on other people, causing me to experience my own inability to meet all my own needs. As someone who is generally able-bodied and is unaccustomed to asking for physical assistance from others, I often find this viscerally frustrating, because it prevents me from working by myself and moving forward at my own pace. But, I have come to value very much that my work teaches me about my own bodily vulnerability, forcing me to experience a need for the help of others. When I first started working with concrete these experiences really cut against the association I always had with making heavy sculpture with a kind of masculine bravado, because the heavier my work became the more beholden to others I needed to be. My sculptures are about support in many ways–all the stools, benches, seats, platforms, shims, and other things made to hold something (or someone) else up. But it also enacts this emphasis on support in its very making, by forcing me into a position of reliance on others, necessitated by its basic materiality.