Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

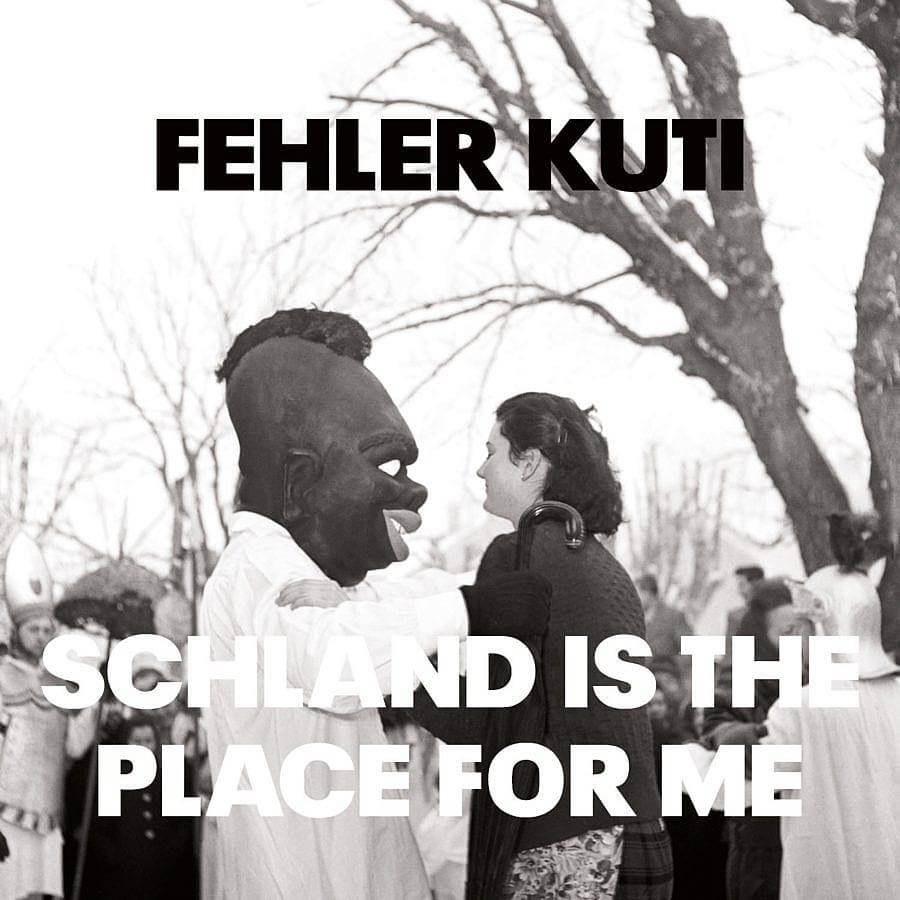

I am a cultural anthropologist working at the intersection of art and academia. I have been doing ethnographic fieldwork for the last few years in several theatre institutions in Germany focusing on race and precarity. I’m looking at the ways in which emancipatory politics are translated into different institutional logics. This research is the basis from which I pursue my artistic practice as a performer and dramaturge, but also as a musician. I am part of the experimental electronic group 1115 and this year I am releasing my first solo record as Fehler Kuti.

What drew you to the medium of sound and music as an expression of the critical theories you’re interested in?

I’m interested in all those little and big misunderstandings. And I think musicians and sound artists are much more accustomed and willing to endure being misunderstood than politicians or academics. To me the „Fehler“ (engl. the mistake) is the most emancipatory part as a musician but also as a listener. there is this whole thing about Americans bringing pop music to post-war Germany and the Germans really digging it, but totally misunderstanding it. Something that Didi Neidhart calls „productive misunderstandings“. In this sense I disagree with some decolonial approaches that seek to contextualize art works in order to make them harder to appropriate. To me, „das Geheimnis“ (engl. the secret) and „der Fehler“ (engl. the mistake) are essential prerequisites for something like „society“ (maybe with a big S) to manifest. It all starts through appropriations and immaterial cultural practices such as singing or playing the piano or just generally listening to music are beautiful examples of misunderstandings AND connectedness spreading like a virus. It’s beautiful.

Can you tell us about the writing/recording process of your single Mayday Mayday?

I was basically fooling around with my circuit bent Casio SK-1 and recorded a few weird noisy melody fragments. When I played them to Markus in the studio, he was immediately psyched and started drumming this „ethnographic“ drum pattern. I think he said it’s from Northern Africa. I can’t remember. It was beautiful. And I immediately added these Busta Rhymes vocals with a few lines of my own. It basically became a song for my newborn son. What is his heritage? Not in an ethnic sense, but in a racialized sense. Is he heir to the same form of alienation that I endure in Germany, or not? And if not, is that a good thing..? Many media outlets have spoken of Mayday Mayday as my warning call concerning racism. But in the original Busta Rhymes lyric, he’s rapping about how dope his rhymes are BECAUSE of the legacy of slavery and how it informs his every move to this day. In this sense MaydayMayday means: WATCH OUT NOW! HERE I COME.

What were some of the biggest influences on your upcoming album Schland Is The Place For Me?

I guess theme wise, the album is my way of working through W.E.B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk and of course his later essay The Souls of White Folk. But I’m also thinking about coloniality and what that means in present day Germany. In a way this record is my rejection of Afropessimism and similar ontological perceptions of racism and a return to Stuart Hall, as a critical race scholar („race is a floating signifier“) but also as a Marxist innovator: to me this record is above all an articulation for his current conjuncture, this current historical moment, in this geography, for this current crisis within progressive movements.

Murat Güngör, a rapper and oral historian, explained to me that Schland is The Place For Me is less Sun Ra’s „Space is the Place“, and more Funkadelic’s „One Nation Under a Groove“. I must admit, he’s right.

If you had to explain your music to a stranger, what would you say?

It’s outsider pop. Groovy, but with a heart of whiteness.

What is one of the bigger challenges you and/or other artists are struggling with these days and how do you see it developing?

Paying the rent.

With alienation being of most interest, how might the term and theories you’ve built around it relate to your choice of a pop sound?

With my previous group 1115 I refused to sing actual lyrics and instead confined myself to onomatopoeia that sometimes evolved into words. I was so afraid of singing words. With this solo record, I dared to sing actual words, but still in an improper way. Sometimes I have a German accent, sometimes it’s British, sometimes it’s American. And then there is this chasm between my circuit bent SK-1 sounds and Markus warm drumming. I think this theme of different forms of alienation runs through the whole production. From the personnel to the choice of instruments to lyrics.

What are you reading right now?

Kultur für Alle (engl. Culture for All) by Hilmar Hoffmann (1979).

What was the last show you went to that stuck out to you?

Motorpsycho.

What do you do when you’re not working on music?

Spend time with my family.

Can you share one of the best or worst reactions you have gotten as a result of your music?

People asking me about my personal accounts of racism. Jeeeez! It’s structural, idiot!